Geoffrey Hartman

Geoffrey Hartman is Karl Young Professor of English at Yale and author of Criticism in the Wilderness and Saving the text.

Placing Leavis

Geoffrey Hartman, 24 January 1985

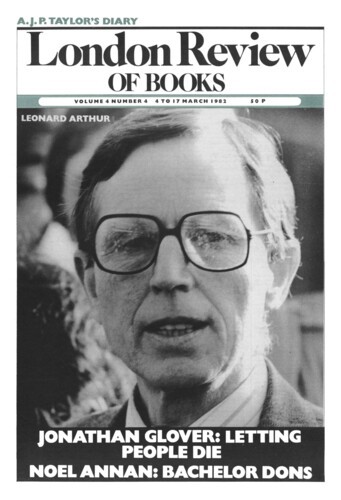

The astonishing importance of Leavis in the English academic consciousness does not seem to be a passing fad. The scandal-maker of the 1930s became, by a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy, part of the saving remnant on which the future of reading would depend. The photo on the cover of Denys Thompson’s The Leavises shows him in a jacket impermeable to the insults of time and with the open shirt of a Labour leader. He looks indeed, as his wife wrote of both of them, ‘grey-haired and worn down with battling for survival in a hostile environment’. Queenie Leavis stands beside him, also dressed simply, sharing his pursed lips and focused eyes that tilt only slightly towards a better world. Together they make a painful hendiadys, an icon of the threadbare, indomitable British intellectual. The snapshot catches something grim and mortal: an embattled uniformity, rather than their spirit active for half a century to save a culture that had lost, so Leavis wrote, ‘any sense of the difference between life and electricity’.

Paul de Man’s Proverbs of Hell

Geoffrey Hartman, 15 March 1984

The death of Paul de Man at the age of 64 deprives us of a literary critic whose influence, already immense in the United States and on the Continent, was beginning to be received in England. This influence is not linked to a large body of published work. De Man’s career started late. His studies in philosophy at the University of Brussels were interrupted by the war; after the war, he emigrated to America, taught at Bard, participated in Harvard’s Society of Fellows, took his PhD only in 1959 (his thesis on Mallarmé and Yeats still awaits full publication), and served as a teacher at Cornell, Johns Hopkins and the University of Zurich before settling at Yale in 1970. And although his earliest essays appeared in French during the 1950s (especially in Critique), they were not well-known until the Minnesota edition of Blindness and Insight (1983) incorporated some of them. Blindness and Insight was his first collection, published in 1971; a second major book, Allegories of Reading, appeared in 1980.

Wild, Fierce Yale

Geoffrey Hartman, 21 October 1982

There are no Departments of Literary Criticism; and even proposals to have a Criticism question in official examinations can cause turbulence in academic circles. What is at stake? By now, of course, a political element has entered, and many suspect that under the name of ‘criticism’ all kinds of illegal goods may be smuggled in. Customs is instructed to make a proper search. Is ‘criticism’ a hidden agenda for Marxism, Lacanianism, structuralist anti-humanism etc?

Reprosuctive

4 March 1982

Pieces about Geoffrey Hartman in the LRB

Where Did the Hatred Go? Criticism without Malice

Adam Phillips, 6 March 2008

Hostility tends to make people sound more powerful than they really are. Eliot against the Romantics, Leavis against Milton, Empson against Christianity, Ricks against Theory. By the 1990s, when...

Theory and Truth

Frank Kermode, 21 November 1991

The autumn catalogues of some very enterprising publishers announce as many books as usual under the rubric Literary Criticism, or possibly more, but few have titles of a sort that, even ten...

Vanishings

Peter Swaab, 20 April 1989

Wordsworth’s poetry has been able to animate critical writing, relevantly, from several different points of view. Narratologists have discussed the gaps in his storytelling and the...

For good or bad

Christopher Ricks, 19 December 1985

Geoffrey Hartman’s Easy Pieces can be hard going. ‘To see, oneself unseen, as at the movies, is only less than the ecstasy of an unseeing seeing: of going beyond the non-language of...

Out of Germany

E.S. Shaffer, 2 October 1980

Rosemary Ashton traces the impact of some German writers, especially Goethe, on the British periodicals and on four writers, Coleridge, Carlyle, Eliot and Lewes; Geoffrey Hartman ranges widely...

The Deconstruction Gang

S.L. Goldberg, 22 May 1980

In reviewing a book on literary theory recently, a noted American structuralist, Jonathan Culler, drew a stern line between the sort of assumptions about literature that might do for ordinary...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.