Claire Tomalin

Claire Tomalin is the author of The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft (1974) and Shelley and his World (1980). She is literary editor of the Sunday Times.

Gnawed by rats, burnt at Oxford

Claire Tomalin, 10 October 1991

George Henry Lewes was a close contemporary of Dickens, born five years after him, in 1817, and dying eight years after him, in 1878. Both men worked themselves to the limits of their strength and endurance, and probably shortened their lives by doing so; both tend to be seen as prototypical Victorians, whereas they were formed by the Regency period and kept a certain flamboyance, together with a dislike of the insularity and hypocrisy to which they saw England succumbing. Dickens, the idol of the public, grumbled, and was forced into secret strategies; Lewes, with much less at stake, proclaimed his atheism and radicalism and braved out his unorthodox marital situations, though even he finally destroyed the letters and journals that would allow us to understand his private history as we should like to. He is best known as the consort and enabler of George Eliot, for which he deserves our homage. But he was far more than that. Although he has been the subject of earlier biographies, he has not been written about with the depth and sympathy that Rosemary Ashton brings to him.

The Sage of Polygon Road

Claire Tomalin, 28 September 1989

Mary who? was the person I mostly seemed to be dealing with in the early Seventies, when I wrote a biography of the extraordinary woman whose works have now been collected for the first time, nearly two hundred years after her death. And ‘Mary Who?’ is still the common form of her name, outside a small circle of specialists and enthusiasts. People stumble over the three simple syllables; its awkwardness has stood in the way of her fame. Pankhurst has an easy ring to it, and Mrs Pankhurst got a statue. When I set about organising a modest plaque on the site of the house in which Mary Wollstonecraft died in Somers Town, there was talk of naming flats or even a street after her: but again, those three syllables defeated too many people. Her nephew Edward Wollstonecraft, an undistinguished and illiberal businessman who emigrated to New South Wales, had a whole district of Sydney named after him, and Australians don’t seem to find it difficult to pronounce: so why do we have so much trouble with his aunt?

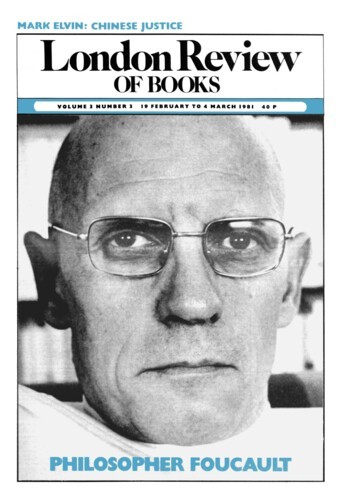

Defence of Shelley

19 February 1981

Scandal’s Hostages

Claire Tomalin, 19 February 1981

‘Madame – vous avez du caractère’, remarked a French gentleman travelling through Savoy in 1823 in the same carriage as Mary Shelley and observing her as she checked her small son Percy’s self-willed behaviour. She was pleased enough to report the compliment to Leigh and Marianne Hunt in a letter; and if she seems a little arch in liking compliments, she strikes the reader too as deserving them. This is the letter of an unusually intrepid and well-educated woman: it mixes affectionate chat about the Hunts’ children and hers with clear-headed comment on her present travels and memories of earlier, happier journeys. At one moment she is describing the Customs officers’ jokes about the seriousness of their work as they lift the lid of her box – Shelley had had books confiscated on the journey out; at another she recalls how the Montagne des Eschelles had given him the idea of his Prometheus Unbound; then she is surprised, entirely on her own account, by the people of Cenis making an annual August pilgrimage to a mountain top: ‘it belongs to that queer animal man alone, to toil up steep & perilous crags, to arrive at a bare peak; to sleep ill & fare worse, & then the next day to descend & call this a feast.’ Through these impressions she scatters idiomatic French and Italian with perfect ease: this is the pen of an undoubtedly quick and clever young woman.

Pieces about Claire Tomalin in the LRB

Rapture in Southend: H.G. Wells’s Egotism

Stefan Collini, 27 January 2022

H.G. Wells resembled a prosperous small businessman who liked to remind people he had served a term as lord mayor. He talked too much, a failing exacerbated by his reedy, high-pitched voice with lingering...

His Friends Were Appalled: Dickens

Deborah Friedell, 5 January 2012

Only after Charles Dickens was dead did the people who thought they were closest to him realise how little they knew about him. His son Henry remembered once playing a memory game with him: My...

Anxious Pleasures: Thomas Hardy

James Wood, 4 January 2007

What is this? ‘Two miles behind it a jet of white steam was travelling from the left to the right of the picture.’ It is a train, viewed across a valley, in Jude the Obscure (1895),...

Grit in the Oyster-Shell: Pepys

Colin Burrow, 14 November 2002

Samuel Pepys was the son of a London tailor and a president of the Royal Society. He was a philanderer who could feed a wench lobster before having his way with her under a chair in a tavern...

Simplicity: What Jane Austen Read

Marilyn Butler, 5 March 1998

Do we need another Life of Jane Austen? Biographies of this writer come at regular intervals, confirming a rather dull story of Southern English family life. For the first century at least, the...

Odd Union

David Cannadine, 20 October 1994

The task of rescuing women from the chauvinistic condescension of male posterity has thus far been unevenly undertaken and incompletely accomplished. Writers and actresses, suffragettes and nuns,...

Nelly gets her due

John Sutherland, 8 November 1990

‘I don’t handle divorce business.’ In general, scholarly investigators should follow Philip Marlowe’s rule. One feels degraded when Dickens’s private letters are...

Mrs Bowdenhood

C.K. Stead, 26 November 1987

Katherine Mansfield, unlucky in life, has been lucky in death. Where some figures sink under successive waves of literary fashion, she remains buoyant. One Mansfield vanishes but another takes...

Shelley in Season

Richard Holmes, 16 October 1980

If all poets have their psychic season, Shelley belongs to the very late stormy autumn and the very early frosty spring. His is a time of transitions: of high winds, wild hopes and freezing...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.