What a Lot of Parties: Diana Mosley

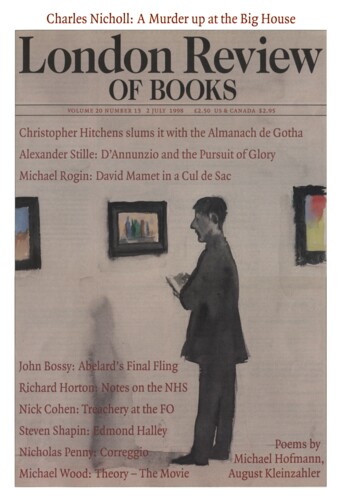

Christopher Hitchens, 30 September 1999

In the autumn of 1980 I was leafing through the latest number of Books and Bookmen and came across a notice of Hans-Otto Meissner’s biography of Magda Goebbels. The reviewer was Diana Mosley. Fair enough, I thought, she had at least known the woman. Indeed, as she put it herself: ‘I knew Magda and Dr Goebbels quite well. She was charming and beautiful, he was clever and witty.’ Eschewing bleeding-heart compassion, yet unusually ready to put in a humane word for the unfit, she found the kindest context for the dwarfishness of her hero, who she described as ‘a small man, not much smaller than Napoleon. He limped because of a club foot, as did Byron. Very clever, he got a scholarship to Heidelberg where he acquired his doctorate.’ Lady Mosley burbled on in this vein for a bit, spicing things up with references to Goebbels’s ‘inspired oratory’. Concerning Kristallnacht she was scrupulously non-judgmental, concluding that ‘his guilt must rest on supposition.’ I remember wondering how she would tackle the ticklish question of the immolation of the Goebbels kinder. Here is how she grasped the nettle: ‘Everyone knows the tragic end. As the Russians surrounded Berlin, the Goebbels painlessly killed their children and then themselves. The dead children were described by people who saw them as looking “peacefully asleep”. Those who condemn this appalling, Masada-like deed must consider the alternative facing the distraught Magda.’ At this point, I threw the mag to one side and seized a pen. It’s true that the shaggy fundamentalists in the Josephus yarn did put their families to the sword before falling on their own, but still … So I wrote a piece for the old New Statesman, emptying the vials over Books and Bookmen and saying rather pompously that I wouldn’t turn in my next review for it until the editor had repudiated the Mosley/Masada trope.‘