Christopher Driver

Christopher Driver has recently resigned the editorship of the Good Food Guide, which he had held since 1969, and is writing a history of British cooking. He is the author of The Exploding University and of The Disarmers.

De Mortuis

Christopher Driver, 28 June 1990

If the Sixties were the decade for penis power, the Nineties are already designed for turning up one’s toes, and at the risk of proclaiming myself as the Fiona Pitt-Kethley of the crematorium, a paid lyricist to fin-de-siècle obsequies, my muse is waiting. I am just about old enough to find myself mourning friends and colleagues younger than myself (a vicissitude endured by my mother, now 92, for a quarter of a century, but that’s the occupational disease of her gender). I took my own mocks for the death examination on a January mountainside a few years ago by observing a little stroke, and I can confirm that hearing is the last sense to go before black-out.

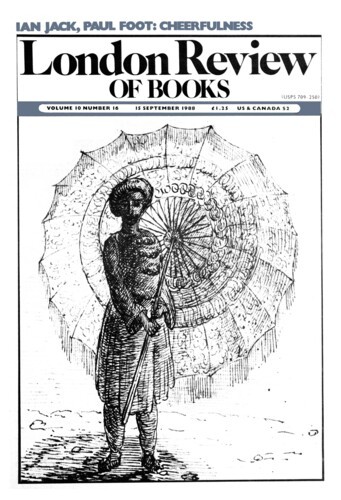

Cad’s Cadenzas

Christopher Driver, 15 September 1988

Composers are supposed to die young, preferably of consumption. Their women, if their tastes lie in this direction, may be called to matrimony and motherhood: but they are seldom given to authorship, and they are not encouraged to own independent musical personalities. These preconditions leave a clear field for the imagination of Hollywood scriptwriters or the industry of Berkeley musicologists. But it is better so. Beethoven’s reputation has survived his sharp practices with publishers, his intermittent problems with servants, and his ‘Battle’ Symphony: but he could hardly have recovered from ‘Life, Laundry and Ludwig: The Diaries of Frau van Beethoven’. At the same time, the composer myth is woefully inaccurate. Haydn, Telemann, Verdi reached their eighties. Anna Magdalena Bach, Constanze Mozart, Clara Schumann and Alma Mahler did more for their husbands’ posthumous fame than a gaggle of critics and sycophants. As for musical cipherdom, the unmistakable rages and affections of Frau Strauss are preserved in the concertante solo violin part of Heldenleben, just as Benjamin Britten’s dependence upon Peter Pears, the sharer of his bed, shines through most of his later music.

Ages of the Train

Christopher Driver, 8 January 1987

It is better to arrive than to travel – these words are being written on a broken-down hovercraft, beached like a whale at Dover – and it was better still, before defiance of gravity and the euphemisms of airports suffused the glands with a cocktail of contempt and funk, to relish le départ. This is because the rituals of arrival and departure require the services and shelter of a station where the rites de passage can be worthily celebrated, with emotions taut and perceptions heightened. In Britain, during a period of stylistic evolution that lasted half a century, railway stations became, both in grandiloquent and in self-effacing modes, the characteristic public buildings of the age, expressing that mélange of optimism, fancy and thoroughness so dissimilar from our own climate of feeling. What better venue than the Gare d’Orsay for the museum of the 19th century which has just opened in Paris?’

Lamb’s Tails

Christopher Driver, 19 June 1986

For a generation now, it has been a commonplace that in Britain food and drink are much discussed. Fewer people seem to notice that this has almost always been so, wherever the capacity to discuss anything is found. Pockets of unawareness are the exception rather than the rule: early redbrick university departments striving to differentiate themselves from Oxford and Cambridge; or the English gentry, who, as Lord Stockton has reminded us, taught their genteel imitators that it was bad form to notice the manna that came to dinner. In other times and places, both hunger and plenty have proved stimulating sauces for food discourse. Miranda Chaytor tells me that the dreams of a 16th-century Northumbrian witch elicited at interrogation centred upon food rather than sex. English diarists – Evelyn as well as Pepys, Thomas Turner as well as Parson Woodforde – confide their meals to paper as readily as their other concerns. One reason why Keats makes better reading than Shelley is that he had a superior gust for eating and drinking, and found a language for it in verse and prose: not just the lucent syrops tinct with cinnamon but the nectarine: ‘good god how fine. It went down soft pulpy, slushy, oozy – all its delicious embonpoint melted down my throat like a large beatified Strawberry. I shall certainly breed.’’

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.