Confirming the Already Confirmed

Stefan Tarnowski remembers Lokman Slim

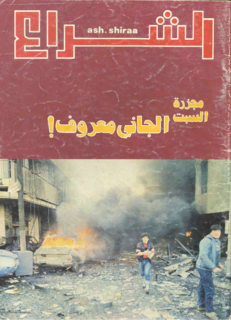

It was during a visit to UMAM Documentation and Research in 2014 that I found out the truth about my grandmother’s death. My aunt, Rania Stephan, was making a film about a car bomb planted in West Beirut in 1983. An AP report from 1991 states the bare facts: ‘5 February 1983: Palestine Research Centre explosion kills 19, wounds 136.’ UMAM’s holdings were more substantial. With the help of the archive’s founder, Lokman Slim, we looked through magazines, newspaper articles, photographs of the explosion’s aftermath. The leftist magazine al-Shirā‘ carried the story on its cover: ‘Saturday Massacre: Perpetrator Known!’Everyone who lived through the civil war knew the motive: to destroy what could have become the Palestinian national archives. No one doubted it was carried out by the Israelis.

My mother had always said my grandmother died from cancer. It wasn’t entirely untrue; she had cancer, but it was the car bomb that killed her. The family home was opposite the Palestine Research Centre. Rania calmly described what happened, telling me the story as if I already knew it: the family gathered in the apartment, the huge explosion, the shrapnel in her back, my usually unflappable grandfather running onto the balcony screaming every swear word he’d never before uttered, my bedridden grandmother covered in glass from the shattered windows. Could I make out my grandfather on the balcony in the background of one of the photographs?

Destroying archives is a radical form of violence. It targets the past, but with the aim of eliminating the possibility of writing history in the future.

Slim set up UMAM in 2005 in his family’s villa in Dahyeh, the southern suburbs of Beirut. His family had deep roots in the once diverse neighbourhood, which was coming increasingly under Hizbullah’s control. Establishing the archive there was brave. Hizbullah was at the centre of a wave of political assassinations. One by one, politicians were murdered until the anti-Assad majority in parliament had been wiped out; and one by one, brilliant, outspoken journalists and intellectuals like Samir Kassir were killed by car bombs. The victims were diverse, but they were united in their opposition to the Syrian regime’s occupation of Lebanon. Everyone knew who the perpetrators were – the Syrian regime and its Lebanese clients – even if they couldn’t prove it.

Lebanon was in the grip of archive fever, and Lokman Slim was at the heart of it. Without openly accessible archives, Slim insisted, there would be no end to ‘the culture of amnesia and cyclical violence’. Together with his wife, Monika Borgmann, and a group of dedicated researchers, Slim set up UMAM to bring documents and evidence together and make them available to academics, artists and lawyers, in an attempt to undermine the regime of impunity.

Last Thursday morning, Lokman Slim was found shot dead in his car. After posters bearing death threats were plastered on UMAM’s walls in December 2019, he announced that the leaders of Hizbullah and Amal should be held personally accountable if anything happened to him. Amanda Abi Khalil, who ran UMAM’s gallery space for three years, told me that the family discovered Slim had written his will in 2005. Had he been expecting it since then?

One of his last interviews came after an investigation revealed links between the ammonium nitrate that exploded in the port of Beirut last August and the Assad regime’s barrel bombs used to suppress the popular Syrian revolution since 2013. The new information, Slim said, ‘confirms the already confirmed’. What he meant, I think, was that we seem to have reached a new paradigm in the relationship between knowledge and power in Lebanon. Even before that investigation, there was more than enough evidence to prosecute.

There are documents proving that the president, Michel Aoun (another former army general-cum-warlord), and every government since 2013 ignored their own officials’ warnings that the ammonium nitrate stored at the port could ignite and wipe out the capital. The president even admitted he knew the ammonium nitrate was there. But what we now know is that knowledge isn’t enough, that power here is immune to knowledge. These regimes are indifferent to the fact that we know every forensic detail of their crimes, their negligence, their histories of violence. They carry on regardless. How can authorities immune or indifferent to knowledge of their crimes be confronted?

The morning after Lokman’s killing, an interviewer asked his sister Rasha al-Ameer if the family wants to call for an investigation. ‘No, we don’t want anything from them,’ she replied. ‘They’ve killed what’s dearest to us.’ The interview asked a final question: do you accuse anyone in particular? ‘No. They’re known.’