Cape Man

Alex Abramovich

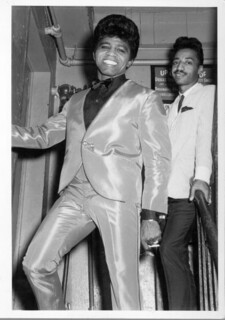

Danny Ray, who died last week, spent forty-odd years as James Brown’s valet and body man. Off stage, he was in charge of the band’s uniforms. On stage, he was Brown’s master of ceremonies and ‘cape man’. It was a job that didn’t exist until Ray joined Brown’s entourage, in 1960 or 1961. When they recorded Live at the Apollo in 1962, Ray’s work with the cape may or may not have been a centrepiece of Brown’s act. By the time they appeared on the T.A.M.I. Show in 1964, it most certainly was.

The T.A.M.I. Show was directed by Steve Binder, who went on to make Elvis Presley’s 1968 ‘comeback special’. Shot at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, and released in cinemas, the concert featured, among others, Chuck Berry, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, Marvin Gaye, the Beach Boys, the Supremes, and a few British Invasion acts. Brown had just scratched the Top Twenty, and then only once, a year earlier, with a cover of the old Russ Colombo song ‘Prisoner of Love’. Still, he expected to close the show. ‘Nobody follows me,’ he said. ‘Actually,’ Binder said, ‘we’ve got the Rolling Stones.’

It was one of the best things to happen to Brown. The Stones were fresh-faced; they’d played in America for the first time that year, while Brown had been kicking around the chitlin circuit for more than a decade. ‘We had to follow James Brown, the tightest machine in the world,’ Keith Richards recalled. ‘That did make me a little tight. Thank God the audience was mostly white.’

Brown’s band, the Famous Flames, opened with their newish single, ‘Outta Sight’. Midway through their second song, ‘Prisoner of Love’, Brown screamed (on key) and fell to his knees. ‘I want you so bad,’ he sang. ‘I want you to try me. I want you to try me. ’Cause you got the power. You got the power.’ He was singing the titles of his other songs – telling his audience which records to look for – but doing something less explicable, too.

‘His songs are the articulation of his need, the elaboration of his great theme, the definition of a man on the verge of abandonment,’ Douglas Wolk writes in his book about Live at the Apollo:

His declaration of abjection will not be denied. He is bewildered, crushed, half-wrecked by thinking you might leave … James Brown screams and sweats and implores … His path is a jagged slash … Nobody else in his band can even break a sweat: they are required to work impossibly hard, too, but they are not to be seen with a hair out of place. James Brown is a vector of chaos, and chaos only means something in comparison to order …

He falls to his knees half a dozen times in every show: on soft wooden floors like the Apollo’s, on hard concrete stages, on carpet, on stone, on metal, on earth … Imagine James Brown falling to his knees for the audience tens of thousands of times, probably hundreds of thousands of times. Imagine the scar tissue, inches thick, on the knees of James Brown.

On the T.A.M.I. Show, the frenzy and drive that Wolk describes coalesce near the seven-minute mark. Back on his feet, Brown sings ‘Please, Please, Please’ – the title of the Flames’ first single, released nine years earlier. A minute later, he’s on his knees again. The backing singer Bobby Bennett walks over and pats Brown’s back, as you would a baby’s. Dressed in a dark, immaculate suit, Ray walks out of the wings and drapes a long cape over Brown’s shoulders. ‘You’ve done enough,’ the gesture says. ‘You’ve done more than enough.’

This is high drama: Brown takes nine or ten steps away from the microphone – and throws the cape off. The show must go on! Bennett leads him back to the mic, where he sings a few bars and collapses again. They repeat the process time and again. In the background, the audience loses its mind.

‘Night Train’, which ends the performance, is a showcase for Brown’s dancing. Prince copied his splits, Michael Jackson the moonwalk. Presley watched the show over and over again. Jackie Wilson – a former boxer, like Brown – was around at the time, and much more popular. Like Brown, he was a phenomenal dancer, right down to the knee-drops and splits. But Wilson was polished; his athleticism went into making it look like he was floating. Brown turned the formula inside out – the work was all on the surface, and part of the point. Brown knew church and jail, poverty, backbreaking labour. He was incredibly hard on his band. He later stumped and voted for Nixon. ‘You had to be watching him at all times,’ Ray said. ‘He would tell me the colour of the suits, the colour of the capes, only a little before the shows … I kept them safe with me and never let them out of my sight, because I knew what they represented.’

In 2005, the year before Brown died, Jonathan Lethem followed him on tour and spent time with Danny Ray. ‘There’s something so marvellous about the cape ritual,’ Lethem said the other night. ‘It’s an attempt to provide care that isn’t wished for.’

James was the only one on stage who seemed to know that he had to give more. And Danny Ray, attempting to pat him down and secure him and console him with the cape, stood in for all of us – our amazement and our own exhaustion. Our sense that the crisis had passed – that James could finally rest. And James’s refusal. His saying: ‘No. I have to deliver more. It’s urgent.’

Brown described the cape routine as a homage to Gorgeous George, the wrestler. But in J.R. Smith’s biography of Brown, published several years after the singer’s death, Ray told a different story:

Back in the chitlin circuit days, there wasn’t no dressing room, there was an outside and an inside, and when you wanted to go off the stage, you went out the door and you were standing outside. I used to catch him coming off singing ‘Please’ and he’d just be drenched in sweat, and one thing I was supposed to do was hand him a towel. That’s all it was. I put the Turkish towel on him. Places were so small, you had to go outside before you come back on the stage. It was, like, our little joke, at first. I put the Turkish towel on him; he’d kick it off and run back in and sing it some more. Folks could see from their seats. People started noticing and it became a thing.

Thanks to Ray, the Flames always looked good. And he, too, was an immaculate dresser. Smith paraphrases the guitarist Keith Jenkins: ‘Ray would save up a perfect, glorious suit for the final days of a long tour; when the rest of the band was down to dirty laundry, Ray would emerge from the bus in a shining, cream-coloured coat, defying all understanding.’

‘He was very small,’ Lethem said.

He was the pilot fish at the shark’s mouth. The remora. He slipped between things … I think he was a talismanic being for the band. For what they had suffered at Brown’s hands. He was, literally, the person who’d held Brown’s coat the longest … He was so loved by that band, such an emblem of the compromises they’d made to be in that brutal, magical aura of Brown’s use.

In the end they all left, but not him. In 1977, Brown and Ray took a Learjet to Memphis. They were given a police escort to Graceland and a private audience with Presley’s corpse. (‘Elvis, you rat,’ Brown said, ‘I’m not number two any more.’) In 2006, dressed in an immaculate suit, Ray draped the cape over Brown’s casket in Georgia. It was Brown’s daughter Deanna who found Ray last week, dead of natural causes. ‘There was a science in the way he threw the cape,’ she said. ‘When he did it, it just nicely laid on the back of my father.’

Comments

-

10 February 2021

at

1:09am

Sebastien Neilson

says:

Lovely piece, thankyou.

-

10 February 2021

at

5:53am

daniel.sayer@gmail.com

says:

Whilst I accept Brown as an amazing performer, this article seems to leave out all the misogyny? That man "on the verge of abandonment" was also a man (often in a rage it seems) who beat up a lot of women, is this not relevant?

-

10 February 2021

at

9:09pm

David Miranda

says:

@

daniel.sayer@gmail.com

This article is about his performances and his ability to mesmerize world wide audiences. Let he who has not sinned cast the first stone.

-

10 February 2021

at

9:13pm

David Miranda

says:

@

daniel.sayer@gmail.com

Let me correct myself: this is about Mr: Danny Ray and his long-standing relationship with the hardest working man in show business. No one did it better. No band was tighter. Danny Ray was the glue! STICK to the issue!

-

10 February 2021

at

9:37pm

freshborn

says:

@

daniel.sayer@gmail.com

The article is about Ray, so no. Not relevant at all.

-

11 February 2021

at

1:51am

william earley

says:

I was among 6 or 7 white boys watching JB perform at Penn State University in the Spring of that awful year----he danced, he shook, he wailed, and implored those "black bunnies to pick out one of those white boys and shake that stuff", he stood there until we were ushered into the middle and off he went.

Read moreFollowing the concert, I waited in the dark to talk to him, he was tiny and muscular and sweaty, even sixty minutes after the show. He cracjkled in that great voice, "I know you had a good time, son----now, show her a better time." He growled half laugh and half bark.

I later ran into him in London in the early 2000's----I reminded him of his comments almost 40 years before and he howled like a hound. Still, he was a showman, an electric man, and a fellow dedicated to doing his best every show, no small price for those he worked with and for him.