At the Migration Museum

Daniel Trilling

On the last weekend before England entered its second lockdown, two slabs of the Berlin Wall were standing on the concourse at Lewisham Shopping Centre. They marked the entrance to the Migration Museum, a roving exhibition space that has made a temporary home in south-east London, near a branch of Footasylum and a stall selling phone cases.

Inside, the museum’s main space was laid out like an airport terminal, for Departures, an exhibition about emigration from the Britain, which has shaped the country’s history (not to mention the world’s) at least as much as immigration to it has. A short film took visitors on a brisk tour of the last 400 years, from early efforts at colonial ‘plantation’ in Virginia and Ulster, through to the 19th and early 20th centuries – when more than 17 million people left Britain and Ireland, mainly for North America – and the more recent period of free movement within the EU.

The empire weighs heavily on this story, both as overseas territory to be settled and exploited, and as a space to relieve the pressures of an industrialising society. A poster from the 1920s, encouraging the settlement of what’s now Zambia and Zimbabwe, showed a ‘typical Rhodesian settler’s homestead’: a farmhouse nestled in a landscape portrayed as both uncultivated and uninhabited.

A protest banner commemorated the Tolpuddle Martyrs, the six Dorset farm workers transported to Australia in 1834 for organising in a trade union. They were pardoned two years later, following mass protests, and came back to England. Most of the 150,000 people sentenced to transportation, however, never returned.

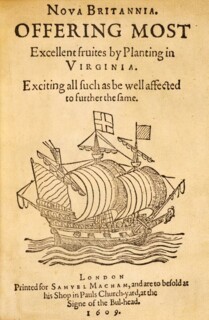

There was often a distance between official rhetoric and reality. Virginia offered ‘most excellent fruites’ to settlers, according to the title page of Robert Johnson’s 1609 tract Nova Britannia, but an indentured service contract told a different story.

The sociologist Michaela Benson is collecting postcards sent by British citizens living in Europe. ‘Moved to Germany in 1987,’ one said. ‘Reasons: the money! Learn a language. Because engineers are appreciated in Germany.’

If the exhibition told a story about people leaving, it was also about people who wanted to maintain connections between places. One of the final exhibits showed portraits of people who’ve recently emigrated. ‘I always felt a little Ghanaian but never quite enough, and also never quite British enough,’ said a young woman called Izzy, whose portrait was on the wall. ‘My ideal situation is to always have one foot in the door.’

‘Departures’ runs until 21 June.

Comments

We drive to Lewisham a lot to go to "Rolls and Rems" a long-established textiles emporium beloved of those who make their own clothes. Lewisham is one of those areas where you see the "real London".

"We're all migrants," I tell our daughters - we're all economic migrants for sure, now. Movement is part of the Brownian motion of market economics.

One thing puzzles me, though. A friend of mine, who has a First in PPE and is one of the new, exponentially ever more left-wing enthusiasts, chides me for talking about expats with nice pads in France and Spain. "Expats is a stupid expression," he says, "they are migrants." They seem a long way to me, with their rather weary and wearying accounts of lunches and dinners out, from what we in SE London know as migrants.