On and around the Moon

Anna Aslanyan

‘Why had we come to the moon?’ the narrator of H.G. Wells’s The First Men in the Moon (1901) asks. ‘The thing presented itself to me as a perplexing problem.’ The novel features in The Moon exhibition at the National Maritime Museum, alongside other books that anticipated the space age: Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon (1865) and Lucian of Samosata’s True Story, written in the second century AD. It begins with a ship blown to the moon by a whirlwind; a war between Phaethon and Endymion ensues, enabled by giant spiders. Aubrey Beardsley was one of the illustrators of an 1894 English edition.

The earliest known telescopic drawing of the moon was made by Thomas Harriot in 1609; he produced a composite map in 1610-13. They are both astronomy and art. The same could be said of John Russell’s late 18th-century moon portraits, which include hundreds of pencil sketches, and his Selenographia, the oldest three-dimensional representation of the moon. James Nasmyth’s telescope, built in 1850-52, towers above the other objects in Greenwich like a white constructivist sculpture. A detailed 300-inch map of the moon made by the amateur astronomer Hugh Percy Wilkins in the early 1950s was used by both the US and the USSR for their space programmes.

One of the questions the exhibition asks is why ‘a number of Soviet “firsts” were ultimately overshadowed by Neil Armstrong’s century-defining “one small step”.’ A possible answer can be found in the images on display. The contrast between the American and Soviet iconography is striking. In a portrait of Armstrong by Paul Calle, who was given access to Apollo’s crew in the final pre-launch days, the astronaut’s self-assured, focused expression tells you he is destined to travel to the moon and back. The certainty that can be read in the face of Yuri Gagarin, photographed in his coffin-like capsule seconds before the 1961 launch, is different: he looks resigned to whatever fate awaits him.

Fritz Lang made his 1929 silent film Frau im Mond in consultation with rocket scientists. The Nazis later banned it because they thought it gave away too many of their rocket programme’s secrets. Forty years later, the Vostok and Apollo launches resembled the one imagined by Lang. There is less obsession with technical detail in Aleksandra Mir’s video First Woman on the Moon (1999). ‘If a woman wants to land on the Moon,’ Mir said, ‘she’ll have to build it for herself.’ She did just that, creating a moonscape for her work – as some conspiracy theorists believe Nasa did in 1969, following Bill Kaysing’s We Never Went to the Moon: America’s Thirty Billion Dollar Swindle (1976).

Attempts to profit from space travel began long before Elon Musk’s SpaceX. The plot of The First Men in the Moon revolves around a business enterprise; in 1950, Thomas Cook offered ‘Lunar Tours’ to those willing to book in advance. There’s a letter dated 1979 from ‘specialists in lunar treks and voyages’ to one Miss Bradbury, telling her that her holiday will have to wait while they ‘inspect flight arrangements and hotel accommodation’.

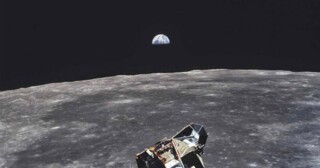

‘Over me, around me, closing in on me, embracing me ever nearer, was the Eternal,’ Wells’s protagonist says after losing his companion, ‘the infinite and final Night of space.’ The two men who landed on the moon in 1969 stayed together; there’s a famous photograph of Armstrong reflected in the visor of Buzz Aldrin’s helmet. Back in lunar orbit, their colleague Michael Collins continued to take photos on his own, and every time he got to the far side of the moon he lost contact with the earth. ‘I am alone now,’ he wrote, echoing the feelings of many explorers and artists, ‘truly alone, and absolutely isolated from any known life. I am it.’