Honest Men Lying Abroad

Eloise Davies

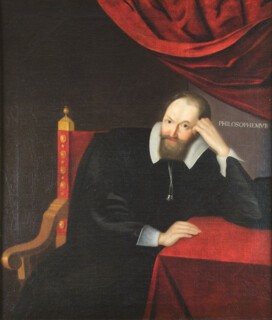

After Sir Kim Darroch resigned as the British ambassador to Washington last week, everyone from leader writers in the Times to George Galloway on Russia Today was quoting Sir Henry Wotton’s line about an ambassador being ‘an honest man sent to lie abroad for the good of his country’. Wotton wrote it in Latin in 1604 in the album amicorum (a sort of early modern autograph book) of a German acquaintance, en route to the Republic of Venice for his first embassy: ‘legatus est vir bonus peregre missus ad mentiendum reipublicae causa.’ It isn’t a pun in Latin, unfortunately: the verb mentior means ‘lie’ as in ‘deceive’ but not as in ‘lie down’.

The joke was soon seized on by England’s enemies. Within a year, the Jesuit Antonio Possevino was citing it as proof of Wotton’s character in a letter he sent from Venice to Rome. It wasn’t until 1611, however, that Wotton’s words gained real notoriety, when the Catholic polemicist Caspar Schoppe published them in his pamphlet Ecclesiasticus auctoritati Jacobi regis oppositus, a vitriolic attack on the government of James I. The king ordered Wotton to publish an immediate apology. But the damage was done. Wotton’s name (and the label ‘Calvinist ambassador’ in general) became a byword for dishonesty.

Unlike Darroch, Wotton had been careless. But his words, though light-hearted and ill-timed, are not untrue. A good diplomat has to say one thing in public while being rather blunter in private. The Venetians, who had pioneered a system of confidential ambassadorial reports, knew this well. Venetian relazioni were coveted across Europe, and often subject to leaks. In 1616 the Venetian ambassador to England wrote to the Senate with concern, having found copies of secret Venetian reports in a library in Oxford.

James too had had frequent occasion to value Wotton’s pretences. In 1601, still king only of Scotland, he had received an Italian visitor called Ottavio Baldi. As Baldi approached the king, he whispered – in suddenly fluent English – that they needed to talk in private. ‘Baldi’ was Wotton, sent by the Grand Duke of Tuscany to warn James of a plot to poison him. He had travelled in disguise for maximum confidentiality, carrying with him a box of antidotes. According to Wotton’s friend and fishing partner Izaak Walton, it was this incident that first won Wotton James’s attention and patronage.

The problem with Wotton’s definition was not so much what he said, but that he had let it become public knowledge. Those with whom he was dealing in Venice and elsewhere knew that ambassadorial ‘lies’ kept the diplomatic world in motion. Wotton’s reputation recovered, and after further embassies to Venice, The Hague and the Holy Roman Empire, he lived out his days as provost of Eton. He is buried in the school chapel. With a final flash of wit, he left his epitaph anonymous:

Here lies the first author of this sentiment: the itch of disputation is the scab of the churches. Inquire his name elsewhere.

The inscription is carved in Latin on a large rectangular slab, across which boys dash to chapel every day; Boris Johnson has surely put his foot in it.

Comments

Best, Amb. Robert Hunter