A wood engraving by the illustrator Joan Hassall, who died in 1988, shows Elizabeth Gaskell arriving at the Brontë parsonage. Patrick Brontë is taking Gaskell’s hand; Charlotte stands between them, arms open in a gesture of introduction. We – the spectators, whose gaze Charlotte seems to acknowledge (or is she looking at her father apprehensively?) – stand in the doorway; the participants are framed in the hallway arch, with the curved wooden staircase behind them. On the half-landing is the grandfather clock Patrick used to wind up at 9 o’clock every night on his way to bed (so Charlotte’s friend Ellen Nussey remembered), though the original grandfather clock was sold in 1861 after Patrick’s death, and in any case stood in an alcove, as its replacement does now, and couldn’t be seen from the front door. Gaskell first visited Haworth in September 1853 – she described it in two letters to friends, one of which she reproduced in her Life of Charlotte Brontë, and Charlotte and Gaskell discussed the arrangements in the letters they exchanged. ‘Come to Haworth as soon as you can,’ Charlotte wrote on 31 August, ‘the heath is in bloom now; I have waited and watched for its purple signal as the forerunner of your coming.’ In the event a thunderstorm before Gaskell’s arrival ruined the heather’s glorious colour.*

Hassall compiled her scene from different sources: Patrick’s profile, with his distinctive high neckerchief (worn, we are told, because of his fear of bronchitis), was copied from a photograph taken late in his life, when all his children were dead and the family famous. Charlotte, looking younger than she would have been at the time (37) and prettier than she probably ever was (more on this later), is copied from George Richmond’s chalk drawing of 1850. Gaskell – the least distinctive of the three – is represented as much by her dress and slightly haughty stance as by her profile. She seems to be looking down at Patrick, though he’s a head taller. Hassall may have used the 1832 miniature by William Thomson of a 22-year-old Gaskell, or perhaps Richmond’s 1851 drawing (there isn’t as much difference between them as twenty years ought to make). She may have made Gaskell up altogether. The parsonage hall is accurately rendered; perhaps Hassall took it from life.

It’s not a particularly remarkable image, just the sort one comes across by accident, one of the many that illustrated the Brontës’ novels and books about them, as well as romances of famous lives, histories of great authors, worthies of the world and other forgotten compilations that conflated fact and fiction and made figures of the day into heroines and legends. There’s something unsettling about it, though, just as there is about a later image (artist unknown), which shows Charlotte at work on a manuscript while Patrick looks on benignly. Gaskell’s warm welcome is more convincing: there is no report of Patrick ever watching his daughters work; he retired to his study in the evenings. It is uncanny, when one knows the portraits and pictures, to see them separated from their originals and placed in new arrangements. What was done when we weren’t looking? They are ready for Woolf’s travesty of a biography, where ‘all the little figures – for they are rather under life size – will begin to move and speak, and we will arrange them in all sorts of patterns of which they were ignorant.’

What is strange about such images isn’t just the extrapolation from fact to fiction, or from bits of fictionalised fact to consummate fiction, or their indiscriminate blending of sources, or the way they alter and animate portraits that are known to us – filling out a dress, making a sitter stand – but the extent to which they are a product of, and perpetuate, a wild biographical knowledge, where unproved or contested facts are written into the story, and even when disproved retain a charge stronger than argument. We see this here: look closely at Patrick’s left hand, which appears to be resting on his infamous pistol. Gaskell reported that Patrick liked to fire his gun out of the bedroom window ‘to work off his volcanic wrath’. He contested this – he had carried one since the Luddite riots only for protection – but later writers took up the pistol as evidence of his uncontrollable anger, his unsociability and supposed neglect of his children. The story becomes a symbol; the symbol works its way back into the picture.

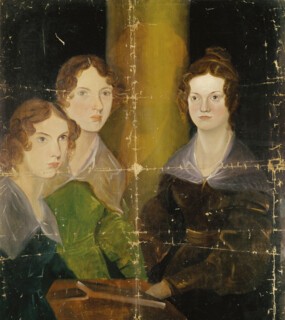

Lots of cavalier things are done with portraits. Images of Charlotte are used to represent Emily and Anne. The surviving part of a group painting by Branwell that almost certainly depicts Anne is often claimed to show Emily. George Richmond’s drawing of Charlotte, taken from life, was later copied by printmakers: engraving reverses the image but not everyone worried about that. A print of the Richmond portrait was the basis for a new painting (is it still right to say ‘of her’?) by J.H. Thompson, which is now the cover of the Penguin Classics edition of Gaskell’s Life. What relationship does this woman bear to the original? Getty Images offers, with no disclaimer, a reproduction of a watercolour from the National Portrait Gallery that for some time was thought to represent Charlotte, though, as E.F. Benson pointed out in 1932, its attribution to Charlotte’s Belgian teacher, Constantin Héger, is laughable: it’s signed ‘Paul Hegér’ (Paul Emmanuel, a character with strong affinities to Héger, is the love-interest in Villette). The date given is 1850; Charlotte left Brussels in 1844. The accent is in the wrong place: Hegér not Héger. It doesn’t look anything like Richmond’s portrait of Charlotte, but that doesn’t bother me as much as it does Benson. Richmond’s portrait probably doesn’t look much like her either; it certainly doesn’t look like any of the women in Branwell’s group portrait of his sisters. Every year, it seems, a different 19th-century photograph is said to represent the Brontës, though there’s no record of them ever having sat for one. A photograph now thought to be of Ellen Nussey was until quite recently said to be a portrait of Charlotte, and was printed on book covers, but the figure is older and stouter than Charlotte can ever have looked.

We seem to want images too much, and not find it odd that there are so many incompatible ones floating about, all said to be likenesses of a person for whom we have no reliable portrait. These images tell us that a person existed, that the stories and achievements, the books and the paintings, were located here – in this figure. Does it matter if it isn’t really a portrait of them, or doesn’t look like them, so long as we know what it stands for? Does it matter what we do with the dead? After all, they don’t exist as people – not legally, not physically. The law insists on room for criticism of those who once exposed themselves to scrutiny. This seems right – they live on only in their work, and in a discussion that can’t be closed – but I’m troubled by their lack of protection. After Gaskell’s biography was published she was threatened with several lawsuits, had to issue retractions and apologies, was accused of misrepresentation by Arthur Bell Nicholls, Charlotte’s husband for the last few months of her life, by Patrick Brontë, by Ellen Nussey and many more. The only ones who couldn’t say anything were Charlotte and her siblings.

Many of the stories in Gaskell are now familiar to any Brontë fan – they are told in every new book, though always slightly differently: quoted by one writer, dramatised by another, paraphrased by a third, contested, exaggerated. At the end of the manuscript of the Life, Gaskell had two sheets of quotations, written out, it seems, to guide her. The first, taken from the Quarterly Review, advises: ‘If you love your reader and want to be read, get anecdotes!’ She did so with remarkable alacrity: in the 18 months after Charlotte’s death in 1855 she read hundreds of letters and interviewed scores of friends and acquaintances, from whom all sorts of interesting tales derive, including the accusation that Patrick Brontë not only took pot-shots out of his bedroom window but also deprived his children of meat (a serious charge given their ill health) and puritanically burned or ripped to shreds any brightly coloured clothes.

Short tales have long shadows. One of the best-known and most picturesque Brontë legends comes from Patrick himself. He told Gaskell (she quotes his letter) that when Anne, the youngest sibling, was four, he played a game with the children, giving each in turn a mask to wear, and telling them to answer his questions freely from behind it. To Anne he asked:

what a child like her most wanted; she answered, ‘Age and experience.’ I asked the next (Emily, afterwards Ellis Bell) what I had best do with her brother Branwell, who was sometimes a naughty boy; she answered, ‘Reason with him, and when he won’t listen to reason, whip him.’ I asked Branwell what was the best way of knowing the difference between the intellect of men and women, he answered, ‘By considering the difference between them as to their bodies.’ I then asked Charlotte what was the best book in the world; she answered, ‘The Bible.’ And what was the next best; she answered, ‘The Book of Nature.’

The most interesting and valuable source of Brontë stories is their own writings. Although we have few letters from Anne or Emily, they wrote a series of Diary Papers – one every four years from 1834, when Emily was 16 and Anne 14, until their deaths – in which they describe their everyday and imaginative lives. Their accounts of being told to ‘pilloputate’ (peel a potato) by Tabby, the Brontës’ longstanding servant, of not having made their beds or practised their scales, their hopes for the future, move seamlessly into descriptions of their writing projects (‘Emily is writing the Emperor Julius’ Life’) and the goings-on in their imaginary world, Gondal. The fantasy worlds that the Brontë children created – Angria for Branwell and Charlotte – grew out of the games they invented for a set of toy soldiers that Patrick bought in 1826. In her ‘History of the Year’ from 1829, 12-year-old Charlotte writes:

Branwell came to our door with a box of soldiers Emily & I jumped out of bed and I snat[c]hed up one & exclaimed this is the Duke of Wellington it shall be mine!! When I said this Emily likewise took one & said it should be hers when Anne came down she took one also. Mine was the prettiest of the whole & perfect in every part Emilys was a Grave looking fellow we called him Gravey. Anne’s was a queer little thing very much like herself. [H]e was called Waiting Boy[.] Branwell chose Bonaparte.

From their stories and the accounts of Gaskell’s interviewees, a vivid picture emerges of the parsonage and its inhabitants: the literary (self-described) eccentric, Patrick, working on his sermons, agitating for local causes and eating his meals alone. Aunt Branwell – Elizabeth Branwell – who came to care for the children after the death of their mother, her sister Maria, and is remembered for clinging on to her Cornwall habits in the cold and windy north: wearing silk dresses and clipping around the stone floors in her pattens. We meet Tabby and the other servants, the curates and the local families with whom the Brontës interacted. The Diary Papers introduce all their beloved pets; cats and dogs (Keeper, Grasper, Rainbow, Diamond, Snowflake, Flossy, Black Tom, Tiger) but also a rescued pheasant and hawk. Already we are acquainted with some of the peculiarities of the individuals – their politics, their passions (anecdotes make us feel like we know them quite well) – and we have probably been introduced, without quite knowing it, to certain talismanic phrases from their writings: ‘we wove a web in childhood’; ‘a chainless soul’; ‘to walk invisible’; ‘give me liberty!’; ‘no coward soul is mine’. Our characters are well established and ready to begin their adventures.

There are far too many books about the Brontës, and books about books about the Brontës, for us to be able to track and arrange our knowledge exhaustively, to separate and rank the different sorts of knowledge we’ve acquired, though Lucasta Miller’s The Brontë Myth (2001) did as much as one might reasonably hope (or wish) to read. Last year was the first of the Brontë children’s bicentenaries: Charlotte was born in 1816, Patrick Branwell in 1817, Emily in 1818 and Anne in 1820. The anniversary books are already many. There are luxury editions, befitting the occasion, and reprints of the novels and of the manuscript of Jane Eyre, updated selections of the letters, non-updated editions of Charlotte’s and Emily’s poetry, books about the novels (scholarly and not), books of essays, books about their belongings, about the parsonage and Haworth, comic books, volumes of artwork inspired by the novels, fictionalised biographical accounts, Brontë A-Zs (which one presumably needs to make sense of everything else).

The most significant book published to mark Charlotte’s 200th birthday was Claire Harman’s Life, the first serious new biography since Lyndall Gordon’s Charlotte Brontë: A Passionate Life in 1994 and Juliet Barker’s The Brontës from the same year (biographies seem to come in generational bursts). All writers on the Brontës now benefit from Margaret Smith’s magisterial – much overdue – edition of Charlotte’s extant letters, published by Oxford in three volumes between 1995 and 2004. Barker and Gordon have both made contributions to this anniversary season: Barker’s publishers have issued an updated version of her selection of Brontë letters and fragments, The Brontës: A Life in Letters; Gordon’s book, Outsiders – a group study of five women – takes Emily as one of its subjects, or rather ‘outsider insurgents’ (Woolf’s phrase), who ‘speak to us about our unseen selves’. Emily engenders that sort of thing more than Charlotte. Brontë books emerge fairly steadily, but the field expands rapidly at moments like these and the major and minor characters suddenly proliferate and reveal multiple selves, with new incarnations not only in books but in exhibitions, plays, TV shows, films. This multiplicity makes it hard to see them clearly: each time I opened a new book I got the feeling I had entered a room just as Charlotte was slipping out of it. But perhaps that’s the wrong way of looking at it. Perhaps each new contribution, while adding another layer to the original, distorting it in a new way, makes some outlines darker and firmer, adds shading or highlights, so that when we stand back the singular touches disappear and the picture begins to cohere.

I should make the first of what I hope need be only a few confessions. We are in the business of history, but also of opinion, of trying to read the characters of the dead. I am not a 19th-century scholar, a Brontë expert, a Brontë fan even. A year ago, I was not interested in Charlotte, or her mysterious sisters or feckless brother, or their eccentric father, and I was certainly not interested in her charming publisher or her upright critics. I was not interested in hearing what the Brontës were, what they have become, or what they were definitely, almost certainly, assuredly, not. I didn’t care to be told that they were actually sexed up and drugged up, and not unhappy or bereft at all. I wasn’t, nor am I, interested in dressing up as them, or seeing how they dressed, or looking at their trinkets. I could imagine myself stretching to reading their letters perhaps, but I had no desire to identify with or be encouraged to identify with them, or to read memoir-biographers doing so. I neither wished to imagine parallels between their lives and my own, nor to be sternly told not to. I didn’t want to play ‘what if?’ or ‘what would?’ games with them. I didn’t want to be told the names of their pets – or to come to realise I somehow knew the names of their pets – or for the stories about them not only to become known to me, but somehow to become part of me. I didn’t want lines of their poetry, or their letters or novels, to loose themselves, or find that others had loosed them and set them floating around to echo in other places, on mugs and T-shirts and gift cards. I certainly didn’t wish to take sides or settle scores. I did not want to visit Haworth.

This wasn’t because I’m not interested, in a historical, aesthetic, anthropological way, in Victorian dresses, or windswept moors, or stories of genius or depravity. I like anecdotes in history books, and sentiment in novels. I am sure that the pleasures of fiction involve some sort of identification, or imaginative sympathy, but I’ve been content to read and reread my favourite books without looking into their creators’ lives. We know a good deal about writers one way or another anyhow, and it might be risky to pry: what is at best a ‘benign literary parasitism’, to quote Tim Parks, could ruin a good novel or poem for ever. It’s not just a question of revelation, of sordid details. I never thought about the reasons I didn’t read biographies, I just didn’t, and now I see that I distrusted them (and still do), that I thought them incapable of dealing in what’s most interesting about people, and I believed that novels were the best renditions of consciousness, of human lives and relationships, and also the most pleasurable. ‘Biography,’ as Hermione Lee says, ‘has so much to do with blame.’ Biographers deal in the back and forth of accusations. I could sniff the mud clinging to them, and if I somehow knew they might bore or disgust me, it may be that I feared they might excite me too. But most of all I felt, still feel, instinctively nervous about putting words into people’s mouths where they have spoken so forcefully for themselves, and perhaps especially where they haven’t. Both things are true of Charlotte Brontë.

Where does one start the story of a life? We come into a world already established; we walk into our lives unseeingly, while biographers get to look backwards, to say where things began. Brontë biographers have to acknowledge straight away not only the great distance separating them and us (or they ought to), but how many hills and trees now interrupt our view. It’s a truism that all Brontë biographers respond to Gaskell, but there are now thousands of other books too. Winifred Gérin, in her biography of Charlotte published fifty years ago, admitted that ‘to add to their number … lays a particular obligation on the biographer to make his purpose plain.’ Rebecca Fraser justified her Life on the basis that the twenty years since Gérin’s had brought much material to light. ‘Yet another biography,’ Barker writes in The Brontës, ‘requires an apology, or at least an explanation.’ Harman doesn’t justify hers: this is an anniversary after all. Like many biographers she begins not with the chronological start of the story, which almost always – following Gaskell – is taken to be the inauspicious birth and remarkable rise of Patrick Brontë, from poor Irish labouring family to Cambridge graduate and learned parson, but with an isolated episode to set the scene. Gaskell takes us on a tour from the train station at Keighley up the road to Haworth, by horse and coach, to the parsonage door and Charlotte’s memorial tablet in the church. Gordon begins with Charlotte aged 23, working as a governess for the Sidgwick family near Skipton in Yorkshire, where her dream of ‘social emergence … is shattered’. Barker starts with Patrick walking up to the gates of St John’s College, Cambridge. This, we say to ourselves, is where it all began.

Harman prefaces her biography with a scene in the present tense. It is, she tells us, ‘1 September 1843 and a 27-year-old Englishwoman is alone at the Pensionnat Héger in Brussels’. This 27-year-old Englishwoman quickly becomes Miss Brontë, and then Charlotte: we are quite close to her now; we are told she finds the empty dormitory at the school where she teaches oppressive, that she takes long walks, that she tells her sister Emily of her ‘low spirits’, though doesn’t tell her how low they are, that she is in love with a married man, the schoolmaster Monsieur Héger. After looking at herself in the mirror and considering ‘a huge brow, sallow complexion, prominent nose and a mouth that twists up slightly to the right, hiding missing and decayed teeth’, Harman’s Brontë walks out of the pensionnat (‘the pain of staying within doors is too much’) and travels beyond the city walls to the Protestant cemetery, where her friend Martha Taylor is buried, and continues on through ‘valleys, farms and hamlets, to … the furthest reach’. Returning, she passes by the Catholic cathedral of St Michael and St Gudula, and (we are now in the past tense) ‘hearing the bell calling the faithful to the evening service, Charlotte Brontë did something strange and entirely uncharacteristic: she followed the worshippers in.’

Charlotte wrote to Emily of that day in 1843 when, alone during the summer holidays, boredom and malaise prompted her, despite her staunch Protestantism, to go into the cathedral, listen to vespers and then request – and be admitted to – confession. In her letter, she describes it quite light-heartedly, calling it a ‘freak’: ‘I felt as if I did not care what I did, provided it was not absolutely wrong, and that it served to vary my life and yield a moment’s interest.’ Harman’s more serious reading is based on the tone of Charlotte’s other letters at the time and her dramatisation of a similar event in Villette, where Lucy Snowe explains her actions by saying ‘I had a pressure of affliction on my mind.’ Harman goes on to speculate about the nature of her confession, presuming that (and she doesn’t tell us so much as lead us up to the conclusion) it concerned ‘the object of Charlotte’s unrequited love’ – Constantin Héger.

Harman’s short preface is striking. She works smoothly – quoting from Charlotte’s letter but also integrating details from the letter into her prose, slipping into a sort of distant free indirect discourse as she lists the defects Charlotte sees in the mirror. The scene is a riff on one in Jane Eyre (the Brontës’ novels continually feed back into the lives), informed by comments from the letters. There is dramatisation and therefore some uncertainties are made into certainties (Charlotte leaves the church with ‘no intention of ever repeating her experiment’) and educated imaginings, like the mirror scene, run straight into real accounts. This is not to suggest that Harman is more problematic than any other biographer – she is a good deal less so in most ways – or that just because we can analyse what she does that means it’s wrong: all writing is a patchwork. But we can begin to see what might be at stake even in the most innocuous decisions; that impulses of arrangement, editing, imagining, are all telling us what to make of our subject.

I must make another confession already. I took Harman’s book to read and review partly – largely – because of my dislike of Jane Eyre. It is crude, undoubtedly, to think of oneself as more of an Austen person, which I did, and to have always been irritated by Jane Eyre in particular of her books, while still enjoying it best (Villette is better I think but less pleasurable). It’s shameful to have avoided studying the Brontës at college, not to have read Anne’s books, or Shirley, or The Professor, or most of the poetry. I grew more ashamed as I read more, not because I changed my mind, or not exactly, but because it quickly became apparent that the things that frustrated me about Jane Eyre – the sense that it had all been written in one splurge, without thought or revision or artistry; the overblown emotions; the unsatisfying mixture of gothic and realism – were concerns that had long since been written off as unenlightened, unfeminist. I wasn’t offended, as were some of the early reviewers of Jane Eyre and Villette (and, more strongly still, of Wuthering Heights and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall), by the ‘coarse’ subject matter or improper feelings; it wasn’t the illicit passions, self-revelation, depression, confessions, representations of cruelty and degradation that bothered me. But I couldn’t help feeling that, in Heather Glen’s formulation, the novels were somehow ‘abrasive, embarrassing, enigmatic: not unproblematically assimilable, but curiously unsettling to read’.

My ambivalence about Jane Eyre, I see now, was not so different from my ambivalence about biography. It had to do with distrusting the storyteller, which is a stranger problem in fiction. It’s not that Charlotte’s narrators are unreliable, though they are, but that the unreliability isn’t always convincingly wielded; the motivations not sufficiently coherent. What are we supposed to make of Rochester? Why is she so hard on Lucy Snowe? Is the happy ending of Shirley a joke? Charlotte’s attitude to her characters wasn’t uncomplicated, and Jane Eyre now seems to me a more interesting problem than it did before. But more annoying than the ambiguity was the sense I had of being strong-armed at points. Do all the Reed family have to be punished? I still find myself resisting the moments of extreme pathos. Rebecca West, writing in the Saturday Review in 1932, attributed this to Charlotte’s personality: ‘She was so used to manipulating people’s feelings in life that she could not lose the habit in her art.’ I don’t think that’s the case, but some of her strategies leave me discomfited.

I also thought for a long time that I had come to the Brontës too late. So much of the special feeling people have for them seems to come from reading the novels at a certain age, usually around 13, and closely identifying with the characters’ rebelliousness and pursuit of freedom. Knowing about their struggles and early deaths (Charlotte lived longest, dying in 1855 aged 38) feeds into the tragedy of the work; one cannot get far into the lives without being affected by it.

All four Brontë children held creative endeavour in high esteem, and Charlotte and Branwell wanted to be published from an early age, so the huge overnight success of Jane Eyre in 1847 – following years of mostly solitary writing, in the midst of Branwell’s decline and after the outlay of part of their savings to self-publish their poetry – is the narrative triumph we have been waiting for, the happy twist of fortune. It’s hard not to take pleasure in Charlotte’s success, and in the deferred success of Emily and Anne, whose books were published later that year, though to consternation rather than acclaim. But this intimacy – this sympathy and admiration – draws us in to thinking we know them, even that we know them better than they knew themselves. We have so much of Charlotte compared to her siblings – hundreds of letters, miles of juvenilia, four complete novels and the start of a fifth, personal testimonies from many who knew her – that it often seems as if biographers are not only replying to Gaskell but to Charlotte herself, trying to catch her out, to show us her inconsistencies and moments of self-deception; to correct her version of things, point to her flaws or else exclude what they find problematic in order to support their particular vision.

Charlotte is an especially interesting and difficult biographical case because she expressed many seemingly contradictory impulses and behaviours. She was shy but thought herself a genius; she was scared of the world but vastly ambitious, she was docile, she was forthright, she was religious, she was scandalous, she was self-indulgent, she was dutiful. She felt – as we all do – entitled to portray things in the ways that suited her, to address herself differently to different people, but, more than that, she maintained complex arrangements of self-revelation even in the small circles in which she moved. Much remained hidden. Her strength of feeling for Héger appears to have been kept entirely secret from her sisters and friends. Her literary endeavours and imaginative games weren’t shared with her friend Ellen until it became impossible to keep them secret, though the women were extremely intimate in other ways (which is not to suggest they were lovers, as some have). Charlotte used pseudonymity, letter-writing, writing in general, not just to speak uninhibitedly, though that was sometimes the case, but to try on different characters – a ‘bitter old bachelor’ for instance when she writes as Currer Bell – to experiment with voice and style, to put on other selves. We must be aware that we are scrutinising someone who made an art of avoiding direct scrutiny.

Harman’s was the first Charlotte I read, and I felt I was in safe hands. But the strength of Charlotte’s own voice is hard to repress, and I began to sense that author and subject did not always align. Harman’s attitudes – her dryness, her lack of indulgence – are very different from Charlotte’s, and I felt uneasy when I could not tell who was speaking. Hints of indignation from Harman on Charlotte’s behalf pleased me, but I was less sure about them when they went against Charlotte’s own sense of events. Biographers, I suppose, must be allowed to differ from their subjects: why should they be in perfect sympathy with them? But signs of frustration with Charlotte annoyed me, as did Harman’s speaking for her subject. Discussing Gaskell, Harman writes: ‘Charlotte looked with amazement on her friend’s life of activity; she could never match it but it provided a valuable example of what was possible for a normally energetic and healthy woman to achieve.’ Charlotte did admire her friend, but she was a very different person – Gaskell was sociable, politically motivated, a busybody (she took it on herself to secretly find a better living for Arthur Bell Nicholls, Patrick’s curate, thinking this was the obstacle to his marriage to Charlotte), and of course she had money. She wasn’t exactly normal; she seems to me more vigorous than most women, then or now. And Charlotte was often very energetic, and reasonably healthy. Did Charlotte look on Gaskell with amazement or do we only think she should have? After Anne was sent home ill from Roe Head School, where Charlotte was a teacher, Charlotte raged at the headmistress, Margaret Wooler, who hadn’t taken Anne’s complaint seriously. Harman wonders if ‘possibly [Wooler] was rather tired of having to deal with her young colleague’s hypersensitivity and was trying to encourage her to snap out of it’.

Charlotte was desperately unhappy while working as a teacher and as a governess, and wrote in the journal from her time at Roe Head about the comfort she took in entering her childhood world of fantasies and stories. Sometimes, as one might in the middle of reading a book, Charlotte lost all sense of her surroundings, even in lessons. The strength of these imaginings is intriguing, but also testament to her unhappiness. Harman calls them ‘phantasms’, and suggests that Charlotte may have taken opium in order to induce them. She quotes Alethea Hayter’s description of the mental traits that (Hayter claims) predispose people to opium addiction, telling us that it represents ‘Charlotte Brontë’s condition at Roe Head with uncanny closeness’:

Men and women who feel all kinds of suffering keenly … who are unable to face and cope with painful situations, who are conscious of their own inadequacy and who resent the difficulties which have revealed it; who long for relief from tension, from the failures and disappointments of their everyday life, who yearn for something which will annihilate the gap between their idea of themselves and their actual selves.

The fact that Branwell took opium is given as further evidence, though we know that Charlotte’s character – and gender – prevented her from behaving in a number of ways that Branwell did. Harman goes on to say that Charlotte’s ‘willed’ removals seem ‘to have a sexual semblance, a masturbatory character,’ which is one way of looking at it (Charlotte as sex-fiend has existed at least since the Héger letters).

The idealisation of Charlotte that grew out of Gaskell’s Life has long since been countered. Some biographers have taken a strange pleasure in deriding her. E.F. Benson, in his biography of 1932, attributed her periods of unhappiness to a constitutional ‘absence of charity’ and ‘bleak censoriousness of others’.† He had come away from the letters he had looked at (they were still in private collections) struck by the ‘ungraciousness’ and ‘acutely censorious eye’ which prevented her enjoying life ‘like a normal human being’. ‘Charlotte was,’ he tells us, ‘entirely devoid of any subtle sense of humour.’ In Rosamond Langbridge’s 1929 account, a ‘psychobiographical’ study, Charlotte is responsible for her own misfortunes. Others talk about her ‘moping’, her ‘self-delusion’ and ‘self-pity’ and ‘hypochondria’ (Charlotte used this word about herself, but it didn’t have quite the same meaning). Particular words recur: ‘neurotic’, ‘pathetic’, ‘bitterness’; she is blamed for not trying harder to get on with other people or being grateful for what she had – ‘one might have thought Charlotte would be happy,’ Barker writes.

But perhaps the problem is not so much with Charlotte as with her biographers. She has had good ones, including Harman, but maybe the sort of person who writes biographies is different from the sort of person Charlotte was. Who writes the Life of a novelist? Someone who loves their books, presumably, and wants to understand the person who created them, but may not write fiction themselves (unlike Gaskell). It isn’t surprising that many of those who have written about the Brontës describe the importance of the novels to them. Adrienne Rich said she had ‘never lost the sense that [Jane Eyre] contains through and beyond the force of its creator’s imagination some nourishment I needed then and still need today’. Barker tells us that ‘if anyone had asked me what was my ambition when I was a teenager I would have said that it was to write a biography of the Brontës.’ Samantha Ellis writes of Emily: ‘Her name has almost become synonymous with wild, unfettered imagination, and when I first read Wuthering Heights, as an awkward, stuck teenager, it made me feel free.’ What sort of problems might these readers run into when they encounter the real person, and find that they are not like them, that they are not always like the heroines in their books, are not, perhaps, likeable at all?

One of the first comments we meet about Charlotte, and I think it must be a critical one, is that she was a ‘self-mythologiser’. According to Miller she invented two myths: ‘one was the positive myth of female self-creation embodied by her autobiographical heroines … the other … was a quiet and trembling creature, reared in total seclusion, a martyr to duty and a model of Victorian femininity.’ Both, she says, ‘had their elements in Charlotte’s private character’. This, it seems to me, only just stops short of accusing her of artfulness. Later, describing one of Charlotte’s letters home from Brussels, in which she imagines herself back in the parsonage kitchen, Miller says that ‘like her later mythographers, the homesick young Charlotte does not conjure up visions of the mills and factories down towards Keighley’ and only just remembers to qualify it: ‘it is hardly likely that she would.’

Both Charlotte and Gaskell have been criticised for making Haworth sound more isolated than it was, though Gaskell’s Life is surprisingly full of local detail and Charlotte can’t really be faulted for reporting her own experience: the family had few friends in Haworth because of their awkward social position – not labourers, not quite gentry. None of the sisters was at ease among strangers, but not being sociable doesn’t mean you’re not allowed to feel lonely. Charlotte’s dramatisation of parts of her life in the novels earned her censure in her lifetime that hasn’t entirely died away, even though we know that this is what writers do and all the people and institutions who might have been slighted are gone. Her portrayal, for instance, of Lowood in Jane Eyre, which she told Gaskell was based on her impressions of Cowan Bridge School, has always been admired for its power, but just as strongly criticised for its perceived distortion of the truth. Gaskell didn’t defend Charlotte’s right to describe things however she liked in her fiction, but suggested it ‘was true at the time when she knew it’ (you can read this more ways than one).

If critics and biographers have sometimes felt that Charlotte complained too much, over-dramatised events, didn’t make the best of things, then they are expressing some of my inchoate feelings about Jane Eyre. And yet it seems unfair to judge a person this way, not least because Charlotte was remarkably self-aware. We should feel lucky that so many of her bleaker letters– which articulate emotional and social turmoil, longing, her grief and sense of injustice – survive. She would mock her own tendencies, but she also saw clearly the constraints of her situation: all the siblings would be penniless and homeless after Patrick’s death, and the only professions deemed respectable for educated single women were teaching and governessing. Charlotte did both. She taught at Roe Head, where she had studied, enabling Emily and then Anne to study there for free; she taught her sisters at home; she went as a governess to the Sidgwicks in 1839, and after six months as a student and then student-teacher in Brussels with Emily, she returned to Belgium, alone, to teach English. She knew how ill-suited she was to both the careers open to her: the former badly paid, exhausting and requiring an authority she felt she lacked; the latter time-consuming, open to abuse, isolating and necessitating an affection for children of which she made no pretence.

Any reading of Charlotte is hugely complicated by her own self-criticism, her sense of familial and religious duty, her sometimes complicated feelings about writing. These are places where we need extra guidance. Was she, for instance, as unattractive as she considered herself to be, as Jane Eyre or Lucy Snowe are supposed to be? What did ‘plain’ really mean? It doesn’t matter to me what Charlotte looked like, but there is a good deal of difference between saying someone is ugly and saying that they think they are. Questions of appearance, of insecurity relating to appearance, arise frequently in the novels – they are close to the heart of Jane Eyre and Villette – and biographers find sources for this in the letters and life. But accounts differ widely. Gaskell recognised the feeling but not the reality. Her description of Charlotte doesn’t make her a beauty, but neither altogether a monster. Ellen Nussey was perhaps flattering in her description that Charlotte’s ‘whole face attracted the attention’; George Smith, the publisher with whom Charlotte had a very involved friendship until his engagement, said that she had ‘little feminine charm about her’. Richmond’s portrait was thought by Patrick to be lifelike but too kind – Charlotte cried on seeing it because it reminded her so much of Emily. Branwell’s portrait, though not wonderfully painted, shows three quite normal-looking women. Charlotte had some missing teeth we’re told: didn’t everyone then? I don’t know, actually, and no one ever seems to tell us. Reading the elaborate critiques of female beauty in the letters one would think the standards were far higher than today, or was it, as Gaskell said, that ‘the idea of her personal ugliness’ had been strongly, if mistakenly, ‘impressed upon her imagination early in life’?

The counterfoil to Charlotte’s self-doubt in most accounts is her ambition: in Harman’s narrative ‘the sense of not being attractive haunted Charlotte all her life and was a further goad to seeking a ruthless sort of independence.’ In 1837, aged 21 and 20, Charlotte and Branwell sent copies of poems they had been working on to famous poets, including the poet laureate Robert Southey. We don’t have Charlotte’s letter to Southey, or know which poems she sent, but parts of her letter are quoted in his and show her extravagant style of praise – she begs him to ‘stoop from his throne of light and glory’ – which he gently mocked, and her desire ‘to be forever known’, which he warned against. Her moments of great confidence, or mock confidence, in her own abilities (in an essay for Héger she wrote: ‘Milord, je crois avoir du Génie’) are problematic for some biographers, because they seem immodest, even embarrassing, or else because they appear to contradict her shyness, social reticence and self-questioning. Some fall on the side of censuring her excess; others, like Margot Peters in Unquiet Soul (1975), wish to cut away the anxiety or attribute it to patriarchy rather than personality (how do we separate self from circumstance?). Charlotte’s desire to be published stands in contrast, at least so it appears, to Emily’s reluctance for it. The story of Charlotte’s discovery of Emily’s poems in 1845, which led to the sisters’ first publishing venture, Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell, has been described as an accident, including by Charlotte, but also as a devious exposure of her reserved sister, not only in reading the poems but in pushing Emily to publish them (the convention now seems to be to put ‘discovered’ in quotation marks).

This seems an odd criticism given that we might know nothing about Emily’s poetry if it weren’t for Charlotte. There are, of course, other instances when Charlotte’s sense of what was best can be read in more than one way. The money that Aunt Branwell gave her and Emily to study in Brussels was originally supposed to go towards setting up a school of their own. Anne seems to come off worst from this, having neither got to go to Brussels nor benefited from the school plan, which was attempted then abandoned three years later. Biographers of Charlotte can hardly object to a decision that they often cite as vital to her artistic development (without Brussels, the narrative goes, no Jane Eyre). But Anne’s defenders might be expected to see it a little differently, as Samantha Ellis does in her new biography of Anne, Take Courage. Ellis is partisan in an almost refreshingly old-fashioned way: she has decided, against the odds, that Anne is the best Brontë and is going to show us why. This naturally gets her into difficulties – it takes some truth-stretching to say Anne was the first of the siblings to get a job (Charlotte supported Anne’s study at Roe Head by teaching there) and wishful thinking to raise Anne’s works above her sisters’, which is not to say they aren’t good. Ellis’s Charlotte is headstrong, blind to other people, especially Anne: she domineers and tramples them. Her selfish desire to study abroad harms her younger sisters’ prospects; her intellectual conservatism silences their more radical natures. I don’t agree with Ellis’s portrayal – I get the sense she wouldn’t expect me to – but there are certain advantages to her approach, not only the obvious value of repositioning the narrative (it’s curious to read ‘Anne and her sisters’) but also the attention given to Anne’s fiction, especially her poetry, which is out of print. This leads to a consideration, albeit superficial, of Anne’s religious and philosophical dilemmas (the vexing question of predestination, for instance), which other biographers dismiss as piety but seems to me helpful in reading her work, and her sisters’.

If Ellis finds Charlotte at fault for her behaviour towards Anne, many more have found Charlotte at fault in her treatment of Emily, who, by tradition (Brontë family tradition, as well as fan tradition), is cast as the most reserved, the most defensive of her privacy and creativity, the least able to cope away from home, the least willing to share herself. We know even less about her than we do about Anne: there are the Diary Papers, a few letters, some striking anecdotes of bravery and nonconformism (and other less positive commentaries), Charlotte’s account of her, and, of course, Wuthering Heights and the poetry. Silence invites speculation: critics initially sought to demonise the author of such a ‘savage’ novel, and later to rehabilitate and promote her, often at the expense of her insensitive and rapacious sister Charlotte. In Outsiders, Gordon avoids this, instead reading Emily against her own writings and against other enigmatic characters: Rhoda in The Waves, Emily Dickinson. She sensibly points to the unhelpfulness of trying to diagnose Emily with anorexia or Asperger’s syndrome, but leaves us only with a different image of Emily’s fatalism. There is, she writes, ‘no institutional habitation for a woman so bared as Catherine Earnshaw, as bared as nature itself in its bedrock stretch’.

Group biographies of unrelated women generally fill me with suspicion, but I can better understand Gordon’s agenda than that of the authors of A Secret Sisterhood, who devote part of their book to Charlotte’s ‘hidden’ friendship with Mary Taylor, a friendship which is mostly hidden in the sense that we know relatively little about it: there are only a few surviving letters between them, and Taylor’s correspondence with Gaskell. It’s not uninteresting to learn more about Taylor, who moved to New Zealand to run a shop and later returned to England in comfortable retirement and wrote a string of novels, but lacking any real detail about their friendship we are left with conjecture and platitudes: ‘Their relationship paints a picture of two courageous individuals, groping to find a space for themselves in the rapidly changing Victorian world.’ It would be more helpful to have a new account of Charlotte’s friendship with Ellen, who is so often written off as ‘limited’.

We have lost sight of Branwell. It is hard to keep in mind that while Charlotte is teaching at Roe Head or going to Brussels or writing Jane Eyre or visiting Ellen, the others are all doing other things (in The Brontës, Barker moves between them fluently). Branwell, to whom Charlotte was especially close in childhood, grew increasingly distant as they got older, then became quite estranged from her after his disappointed love affair with Lydia Robinson, the wife of his and Anne’s employer, led to a complete collapse into alcohol and opium addiction. (Anne tutored the Robinson children from 1840 to 1845; Branwell joined her to teach the son in 1843.) Opinions differ as to the nature of the affair and whether or not it largely occurred in Branwell’s head; we have Charlotte’s account of his dismissal, but not the precise reason. Gaskell was threatened with legal action – unsold copies were recalled and apologies issued – after she followed the Brontë family story in the Life and laid the blame for initiating the affair with Mrs Robinson. Branwell bragged about it (‘my mistress is DAMNABLY TOO FOND OF ME’) but this is hard to interpret: the letters of his that we have are mostly in a style more extravagant than Charlotte’s and less modulated. The final months of Branwell’s decline are reported quite openly in Charlotte’s letters to Ellen, and, more obliquely, in her other correspondence. This has led to the charge by some biographers – not just of Branwell – that she was crueller to him than her sisters were (they mention his ‘illness’ only briefly in their Diary Papers). Branwell gave the whole household a good deal of misery but Charlotte is additionally indicted for hypocrisy in criticising Branwell while nursing her own ‘secret passion for a married man’, as well as a lack of charity in expressing her sense of his wasted potential after he died in September 1848. ‘He had committed the unforgivable sin of not living up to her expectation of him,’ as Barker put it. Harman says that Charlotte’s anger was not simply legitimate grievance and worry: she was ‘secretly furious at the ease with which he had been able to indulge his passions while she was almost killing herself with the suppression of her own’.

Charlotte’s tendresse for Constantin Héger is known through four letters that his daughter revealed in 1913 (Gaskell had seen them, at least in part) and through what we assume to be portrayals of him in her novels: the Belgian teacher Paul Emmanuel in Villette, Crimsworth in The Professor, and, to some degree, Rochester in Jane Eyre and Louis Moore in Shirley. After the death of Aunt Branwell brought Charlotte and Emily home from Brussels in 1842, Héger wrote to Patrick Brontë expressing his admiration for their diligence and the hope they would soon return. Charlotte went back alone, though the salary for teaching was less than she would receive in England, and the year she spent there was increasingly unhappy, as first Zoë Héger, then Constantin, seemed to withdraw from her. Charlotte wrote of it to Ellen in confusion – ‘You will hardly believe that Madame Héger (good and kind as I have described her) never comes near me on these occasions … Is it not odd?’ – which Gérin sees as a sign of her innocence (though what is she guilty of?): if Charlotte’s admiration for Héger had become too great, too visible, she herself must have been ignorant of it. To what degree Charlotte was aware of it, to what degree it was a sexual attraction and what expectations she had of it is impossible to say. Perhaps she deceived herself; perhaps she didn’t care. The configuration in Villette, where Lucy’s romance with the teasing professor Paul Emmanuel prevails over the machinations of evil Madame Beck, might be a form of wish fulfilment, but that doesn’t mean Charlotte saw her own feelings simplistically.

Charlotte and Emily had taken private French lessons with Héger: the compositions Charlotte worked on with him, the interest he took in her writing and ideas and the (sometimes quite strict) instruction he gave clearly led to an intense attachment on her part (Emily and Héger ‘don’t draw well together’, Charlotte wrote). She had not had many opportunities to show her work to someone she looked up to, to be assessed and encouraged, given books to read and asked her opinions of them. Héger, judging by a letter to another pupil, could be imperious but also self-deprecating; flirtatious, informal. When Charlotte returned to Brussels there was a new dynamic too: she became his teacher, giving Héger and his brother-in-law English lessons, until suddenly the lessons ceased. At the end of the year, quite desolate, she resigned and went back to Haworth, but she wrote to him. The earliest letters are missing but by July 1844 Héger had requested that their correspondence be limited to every six months, and then he stopped replying at all. Charlotte sent messages with friends, thinking, perhaps, that hers were being intercepted by his wife. The letters we have show her desperation – in January 1845 she wrote to him that ‘day and night I find neither rest not peace.’ She didn’t declare love, but begged for the resumption of their former discourse:

Monsieur, the poor do not need much to live – they only ask for crumbs of bread which fall from the rich man’s table – but if one refuses them these crumbs of bread – they die of hunger – Nor do I need much affection from those I love – I would not know what to do with an absolute and complete friendship – I am not used to such a thing – but you once showed me a little interest when I was your pupil in Brussels – and I cling on to preserving that little interest – I cling on to it as I cling on to life …

It is easy to quote this, and it is so often quoted that it begins to seem more like literature than life. Gordon reads the Héger letters as an ‘imaginative act’, as though they were an extension of Charlotte’s essays for him. But many, and not only Gaskell, have had qualms about publishing the letters. Most have been nervous about the response they might elicit – that Charlotte would be judged harshly – but it seems to me that we ought more to be nervous about the ease with which we use and reproduce (for what effect?) lines formed by such intense emotion and written in such secrecy. We can do what we like with her work: the novels have, after all, ‘voluntarily exposed themselves to scrutiny’. And now we are almost at the heart of the adventure. It was only a few months after writing this letter that Charlotte discovered Emily’s poems, and, as she described it in her (controversial) Biographical Notice to the 1850 edition of Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey, the dream of being published ‘took the character of a resolve’.

What interested me most about Harman’s description of Charlotte’s reveries wasn’t the notion that they might be drug-induced, or inappropriate or adolescent, or unhealthy for her (as Charlotte sometimes felt, calling them ‘morbidly vivid’) but how powerful they were and what, if anything, they might tell us about her imagination. Gaskell describes Charlotte’s approach to novel writing as relying, at least for plot, on unconscious methods: ‘She said that it was not every day that she could write … some mornings she would waken up and the progress of her tale lay clear and bright before her, in distinct vision.’ In those ‘phantasmic’ accounts from her time at Roe Head, Charlotte describes scenes coming to her lucidly: both characters from her created worlds (while everyone is sitting at tea she is ‘on the shores of the Calabar, looking at a defiled and violated Adrianopolis’) but also unfamiliar, intriguing images: a mysterious woman in a darkened hallway, waiting for someone … She often wrote with her eyes closed, which Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar use for their argument that she was ‘essentially a trance writer’. The debate about how ‘instinctive’ (therefore less impressive to some) her process was doesn’t seem to me to be the best way of evaluating the books, though it would be interesting to know. The problems in Jane Eyre aren’t to do with a failure to produce an effect on the reader, but with the sort of effect it is and what it serves. More interesting is that these accounts, as Gérin says, describe ‘the actual creative process at work’. After all, most of us have rather weak powers of imaginative projection. ‘It is not hard to imagine a ghost successfully,’ Elaine Scarry writes, ‘what is hard is successfully to imagine an object, any object, that does not look like a ghost.’ As Woolf pointed out, Charlotte’s ghosts seem more real than many real people.

Although Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell only received a few notices, they were encouraging enough for the Brontës to think of developing longer works for publication. The inheritance of £300 the sisters had each received from Aunt Branwell, while not enough to live on, made it possible for them to put off paid employment while Branwell was ill and Patrick suffering from cataracts. Wuthering Heights, The Professor and Agnes Grey were sent to various publishers in 1847 (Charlotte famously crossing off the name of the last one on the packet before sending it on again, so each publisher could see the story of its rejection) until Thomas Newby accepted Emily and Anne’s books, though they would have to pay £50 for the pleasure, to be returned if 250 copies were sold. Charlotte sent out The Professor again, and after a kinder than usual rejection note from Smith, Elder & Co, saying they would like to see other work, she promised to send them ‘a second narrative in 3 vols now in progress and nearly completed, to which I have endeavoured to impart a more vivid interest than belongs to the Professor’.

We know little about the creation of Jane Eyre. The sisters kept their writing secret, so there are no letters describing Charlotte’s ideas and decision-making. There are no notes, roughs, sketches, drafts; only the fair copy of the manuscript Charlotte sent to Smith, Elder & Co. John Pfordresher, in The Secret History of ‘Jane Eyre’, claims that ‘Brontë’s need for secrecy seems to have driven her to destroy everything about the making of the book,’ but it may be that she worked as Gaskell describes – writing only when she had a clear idea of what she wanted to say and revising little. She certainly worked quickly: getting as far as Jane’s departure from Thornfield (around 70,000 words), according to Harriet Martineau, in less than two months. The start of this work has a myth of its own. Charlotte was in Manchester, unable to leave Patrick who was recovering from his cataract operation and had to lie in a darkened room for weeks. She had just received the latest rejection note for The Professor. We imagine her, in Harman’s words, as she ‘bravely put the parcel to one side, got out her pencil and little homemade paper notebooks, and in the dismal Manchester lodgings began something entirely different’. It is one of those narrative junctures when, at the lowest point, suddenly someone sprinkles some fairy dust. Pfordresher writes: ‘at this moment, in this place, Brontë picks up her pen and writes, “There was no possibility of taking a walk that day” … these words … spring from this immediate moment in Brontë’s life. Trapped, she begins to spin an imagined tale that will permit her to escape.’

We are already in trouble here: in the novel Jane goes on to tell us that she doesn’t like long walks, so the leap from life to literature can’t be as simple as it seems. But although I don’t believe in fairy dust, I can see that there is something thrilling about the fact that we know what is going to happen and Charlotte doesn’t (you can do it, Charlotte!), that this book is going to make her famous. But because this isn’t fiction, it goes two ways: Charlotte knows something we don’t, can’t, account for. How is it that one moment there was no Jane Eyre, and the next there was something that became Jane Eyre? Pfordresher’s book is an attempt to take us behind this veil, to show us the mechanisms; a biography of a book, as it were. Like other biographies, his relies on a patchwork method: some of it quite helpful literary detection – drawing out linguistic echoes between her letters and the novel, analysing what we know or think Charlotte read that might have inspired her – but mostly moving with confidence through a disarming array of different types of ‘evidence’. In one passage, describing what he believes to be the influence of her experience as a governess on the depictions of tyranny and imprisonment at the start of Jane Eyre, Pfordresher proceeds from a discussion of Agnes Grey, Anne’s account of the trials of a governess, to a quote from Gaskell, to one from Jane Eyre, to the letters, to pure speculation: ‘she remembered her experiences, and those of her sister Anne, as she sat down to write that novel’s first chapters.’

Pfordresher is on surer ground when he looks at the development of ideas and forms in the juvenilia, though again it seems that the only way to account for the change in style between the fantastic tales of Angria and Jane Eyre is to look to what we might surmise of the life. An excessive literalism leads him into some predicaments: if Charlotte ‘guarded with jealous hostility’ the secret of her love for Héger, why did she put it in the book? Who are the Brontës anyway, given that they ‘feel far more themselves adopting names and sometimes roles quite different from who they actually were’? If this seems wrongheaded, at least Pfordresher is forced to acknowledge his uncertainties – some critics are sure they know the origins of the novel. ‘The book was the product of two main ingredients, wrought in the crucible of Charlotte Brontë’s mind: her overwhelming feelings for Héger and Branwell’s own guilty passion,’ Rebecca Fraser tells us.

Others don’t try to claim so much. The authors of Celebrating Charlotte Brontë suggest ways that ‘life transformed into literature’ by taking us through Jane Eyre chapter by chapter, offering source material for each of the novel’s developments. Some of the most interesting things they look at are physical rather than abstract (mostly artefacts from the Brontë parsonage, which published the book), allowing them to digress, where biographers often don’t, into styles of clothing, attitudes to women’s hair, the making of lace cuffs, what dressing cases looked like and how a writing desk was really a sort of wooden tray you put on your lap. There is the inevitable struggle to bridge the imaginative gap: is the decorative china that pleases Jane so much at the start of the novel like the china the Brontës had, as they implicitly suggest, which might tell us something about Charlotte’s own childhood recollections, or is Charlotte thinking of something grander, like the tea things she admired in the houses of wealthier friends, which would suggest a different sentiment? We don’t know. We only know that her characters notice patterned tea cups and that she had some. The Brontë parsonage is itself a curious mixture of the authentic and the replacement; a composite of different parsonages pieced together from letters and sketches and reminiscences. It doesn’t exactly pretend to be what it was at any particular moment in the past, but neither is it easy to keep in mind that this place of preservation and memorialisation is telling us lots of overlapping stories at once.

The material world of the novels is incredibly rich, and, since the Brontës’ poverty was for a long time over-emphasised (Barker accuses Charlotte of doing so herself, but these things are relative), it’s perhaps not surprising that writers should consider the ways in which the things they had or saw appear in their work. Charlotte, Deborah Lutz points out in The Brontë Cabinet, loved ‘bits’, and thought of calling Villette ‘Choseville’. Her book is most fascinating not when it looks at the relics, the walking sticks and tiny shoes, but at the great mass of writerly and literary paraphernalia associated with the Brontës; the paperiness of their lives. This means not only their books, and the tiny books they made as children, but the endless reams of paper required for their writing, which sometimes sent the Haworth stationer walking ten miles to Halifax and back (so he told Gaskell) to ensure he had enough for them. There were paper shortages during the Napoleonic Wars and paper taxes until 1860; writing was an expensive business, so handwriting was small and letters sometimes cross-written. Charlotte’s characters have ‘blue embossed, hot pressed satin paper, sealed in green sealing wax’; letters were usually sealed with coloured paper wafers, which were printed with images or mottoes (‘delay not’, ‘truth’, ‘time explains all’) – another way of saying things – which Charlotte would further alter to make puns or secret messages. Letter culture was rather different from what we know: postage was paid by the receiver rather than the sender – hence Charlotte’s apologies to Ellen for costing her so much – and it was cheaper to send parcels, so letters were slipped into newspapers and packages. The Brontës often passed their letters on to one another; there are many mentions of letters being read aloud and instructions on what not to say given this fact. A letter might separately address more than one recipient, or enclose another letter. Because the envelope was made from the letter itself, it had folded and unfolded expressions. One doesn’t often get a sense of this physicality, or what we might learn from it, from reading bits of the letters in books. What difference might it make to our sense of things if we read a printed excerpt from a confessional letter of Charlotte’s to Branwell, and then see elsewhere that the original has a little note to Anne, in quite a different tone, added at the bottom?

This is one of the drawbacks of Barker’s recently reissued The Brontës: A Life in Letters, which extracts from the family correspondence (most of it Charlotte’s) in order to tell the story. Which story are we being told? If we only see the parts of the letters that give the ‘plot developments’ (and, as we know, much went unrecorded) we lose not just the texture of the lives but the strangeness of them. It is helpful to see images of the letters, or see the real things, not because they bring us closer to the people who wrote them (or the story we have of them) but because they remind us of how removed they are, that they did and thought all sorts of things of which we might get odd hints but can’t really know or explain. Barker writes, rather strangely, that ‘one cannot help agreeing with Arthur Bell Nicholls that it is morally wrong to make public letters which were intended only to be seen by one or two well-known and trusted recipients’; but the problem is not with the letters themselves (though the history of their great dispersal and reformation is fascinating and terrible) but what is done with them – how they are cut and elided, presented, interpreted. Barker aims to let the Brontës ‘speak for themselves’, but there are different sorts of speaking: Barker speaks in what she puts in and what she leaves out; the Brontës are silenced when we are not given the explanatory footnotes or interleaved comments that help us make full sense of them.

Margaret Smith’s selection of Charlotte’s letters from 2007 – the trade counterpart to her Oxford University Press undertaking – misses out many valuable things, but gives much more space to Charlotte in her vagaries: her different voices, different accounts of the same events, her asides and apologies, her playfulness and oddity. There is an inherently uneven distribution. Most of the letters written before 1847 are to Ellen; after the success of Jane Eyre Charlotte had a wide range of new correspondents. These included her publishers, especially George Smith and William Smith Williams, as well as critics and writers with whom she talked about her books and other people’s. Perhaps because we are missing earlier letters, perhaps because after the deaths of Emily and Anne in 1848 there was no one with whom to share her ideas, there is a sudden wealth of literary commentary in Charlotte’s later letters and we hear her opinions on Thackeray, Dickens, Fielding, Scott, Austen, Gaskell, Oliphant, Mill; her theories about literature and the dangers of it; aspects of her artistic decisions:

I called her ‘Lucy Snowe’ (spelt with an e) which ‘Snowe’ I afterward changed to ‘Frost.’ Subsequently – I rather regretted the change and wished it ‘Snowe’ again. A cold name she must have – partly – perhaps – on the ‘lucus a non lucendo’ principle – partly on that of the ‘fitness of things’ – for she has about her an external coldness.

There is a great deal of humour in the letters, and wonderfully lively accounts of events (I suppose this is a sort of biographical rendering too) – of being taken to the opera, unexpectedly; an awkward dinner at Thackeray’s; Harriet Martineau’s morning routine (cold baths). There are passages of great beauty, grief and sentimentality, too, and all in what seems an irrepressibly writerly voice, as when, in 1854, she informs Ellen that Arthur, Charlotte’s new husband, insists they burn each other’s letters after receiving them (which Ellen ignored) or else write

such notes as he writes to Mr Sowden – plain, brief statements of facts without the adornment of a single flourish – with no comment on the character or peculiarities of any human being – and if a phrase of sensibility or affection steals in – it seems to come on tiptoe – looking ashamed of itself – blushing “pea-green” as he says – and holding both its shy hands before its face.

We see Charlotte more vividly here than we do in any of the biographies, which is presumably the reason Gaskell printed so much of Charlotte’s correspondence in the Life.

It has taken us a long time to get back to Elizabeth Gaskell arriving at the parsonage. I didn’t want to visit Haworth, but I did, twice. Haworth is a small mountain, it seemed to me, with the parsonage at the summit, the tourist village below and the modern town spreading out across foothills. The moors beyond Haworth make an impression on everyone: I was struck, conventionally, by the sudden openness and, looking across the valley, by the sight of great banks of cloud rapidly moving and changing. It was a drizzly kind of day, and the effect of light and colour where the clouds met the heather was peculiarly bright with un-English green and orange and pink. I can bring the impression to mind quite clearly.

Gaskell thought the landscape around Haworth was intrinsic to her subject, to the whole family; her descriptions of it, despite the long tradition they instigated, are fresh and original. Gaskell’s Charlotte, when we return to her, is wonderfully fresh too, still as curious and sensitively rendered, even if, we now know, she is deprived of some of the intensity of her colour. Gaskell saw Charlotte’s potential as a subject even before she befriended her – ‘I have been so interested in what she has written … the glimpses one gets of her and her modes of thought, and all unconsciously to herself, of the way in [which] she has suffered’ – and it’s hard to untangle this from her desire to improve her friend’s reputation: both benefited Gaskell’s own work and agendas. But one never feels Gaskell’s designs are entirely hidden, even if some of her techniques (conflating letters and so on) are. Her subjectivity announces itself; she frequently, disarmingly, refers to areas where she cannot make up her mind, cannot reconcile different accounts or the contradictions of an individual. For a long time it was thought you had to have known someone to write their biography, and there is something in that: not because the insights are necessarily greater, but because if you care about them you take more care over them. I called Gaskell a busybody before, and didn’t mind at all: to me she’s a name to conjure with, whereas Charlotte has become a real person.

It’s easy to read the Life critically now, when so much work has been done in response to it and it is situated with appendices and introductions and notes on the text. But it remains a surprising book; as with Charlotte’s letters I am struck by the sense that Gaskell is more complex and interesting than her critics, that she has subtly and cleverly done what she has done. Gaskell’s Patrick Brontë is not quite so awful as is generally made out; her Branwell is unsympathetic as an adult but not as a child; she shows us the mills as well as the moors; she reads Charlotte with elegant sympathy. She may not know what to make of the novels but she devotes a good deal of space to Charlotte’s literary character and opinions. Her account of the woman she knew, like those of the people she quotes, has all the partiality of reminiscence and we take it as such. And, of course, it is half Charlotte’s book anyway, since Gaskell reproduces so much of the letters. Two quotations from them relieve me of my concern for Charlotte, who was quite capable of putting down excessive praise and laughing at the mistakes of biographers. From a letter to Ellen:

I enclose a slip of newspaper for your amusement – me it both amused and touched – for it alludes to some who are in this world no longer. It is an extract from an American Paper – and is written by an emigrant from Haworth – you will find it a curious mixture of truth and inaccuracy, return it when you write again.

And from her reply to an admirer: ‘I must also disclaim the flattering side of the portrait. I am no “Young Penthesilea mediis in millibus” but a plain country parson’s daughter.’

Are lives like folk songs, or jazz standards, which are given a new interpretation by each singer, and we simply choose our favourite? When I began writing about Charlotte I made a list of things to avoid, the opposite of Gaskell’s page of instruction. I wrote that I must be careful not to be autobiographical, even implicitly. I must not pass judgment on my actors or play them off against one another. I must not dramatise and I must not generalise. I shouldn’t claim to know what people felt or thought, or try to suggest I can answer things which can’t be known. I mustn’t report events as though they were stories, or read real people against fictional characters, like thinking Sylvia Plath is Isabel Archer. I must not speculate too wildly or infer things from their negatives. I mustn’t cover up anything surreptitious that I do. I must try not to extract moral principles from lives. These are hard rules to write under and one fails: quotes are always cut, arguments made, and I think perhaps it is not what we do with biography that matters so much as the spirit in which we do it. Biographies behave more like novels than legal reports – Gaskell’s is often treated as such – but they have something serious at stake. If we can think about the emotive power of novels like Jane Eyre, their symbolic and affective structures, their hierarchies of information, the voice which unfolds their events – all the sentiments and strategies of the authorial imagination – then we can bring that thinking to biographies when we read them too; more urgently and more critically than we do with fiction.

I have extracted a moral – indirectly – about my frailty as a reader. It’s uncomfortable to see your own prejudices, to discover that you have an unquestioning belief in ‘the hidden mechanisms of a sovereign self’, as Christopher Clark puts it; to sense your own partiality for the anecdotal. But I still think it’s dangerous to spend too much time with the dead. Rising from my desk late one evening, I am suddenly confronted with a scene. I see myself pulling back my field of vision – stretching out and grasping it like a taut piece of cloth – and looking down through the opening onto the parsonage dining room. It is dark. As my eyes adjust I see two figures sitting at the table: Charlotte, animated, leaning forwards into the candlelight; Anne, with her back to me, listening, pencil in hand. Emily is pacing; she has almost reached the end of the room by the window. The sounds of the traffic are gone, there is only a thick sort of silence and Charlotte’s voice, not at all how I expected it, and Emily’s footsteps.

It lasted no more than a second, but it seemed like a bad omen. Something that was outside had managed to get in. I don’t want to have a fixed Charlotte, even only in my mind. I want to shake up all the different stories, all the facts and facets, until they settle into new configurations; or better still, to keep them in constant motion, like a Calder mobile, forever shifting and rotating, forming new patterns out of the same elements; or like the weather drifting over the hills, its grand character continually inflected, full of tiny, rapid, almost imperceptibly subtle flickers and changes of hue. Richard Holmes gives one of the accounts of biography I like best: the writer will never catch their subject, but might describe the pursuit of that fleeting figure. I would like to let her go.

Among recent books consulted in the writing of this piece:

Charlotte Brontë: A Life by Claire Harman (Penguin, 446 pp., £9.99, April 2016, 978 0 241 96366 1)

The Brontës: A Life in Letters by Juliet Barker (Little, Brown, 464 pp., £25, April 2016, 978 1 4087 0831 6)

Outsiders: Five Women Writers Who Changed the World by Lyndall Gordon (Virago, 325 pp., £20, October, 978 0 349 00633 8)

Take Courage: Anne Brontë and the Art of Life by Samantha Ellis (Chatto & Windus, 343 pp., £16.99, January, 978 1 78474 021 4)

A Secret Sisterhood: The Hidden Friendships of Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, George Eliot and Virginia Woolf by Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney (Aurum, 254 pp., £20, June, 978 1 78131 594 1)

The Secret History of ‘Jane Eyre’: How Charlotte Brontë Wrote Her Masterpiece by John Pfordresher (Norton, 256 pp., £20, August, 978 0 393 24887 6)

Celebrating Charlotte Brontë: Transforming Life into Literature in ‘Jane Eyre’ by Christine Alexander and Sara Pearson (Brontë Society, 204 pp., £25, March, 978 1 9030 0716 7)

The Brontë Cabinet: Three Lives in Nine Objects by Deborah Lutz (Norton, 247 pp., £13.99, April 2016, 978 0 393 35270 2)

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.