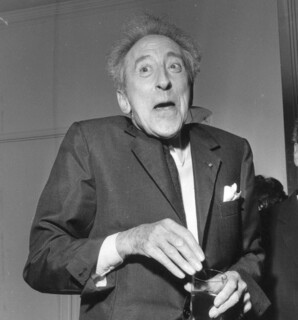

Jean Cocteau had a genius for being seen. As an elegant young man, with the cult poet Anna de Noailles on his arm, thanks to an introduction from Proust, he danced the polka at the Bastille Day ball in 1912, careful, first, to alert the photographers. ‘If I were to take a picture of a village wedding,’ a photographer once remarked, ‘Jean Cocteau would appear between the bride and groom.’ Across the span of his life he appears in snaps with Stravinsky, Picasso, Piaf, Chanel, Charlie Chaplin. A picture from 1958 captures an elderly Cocteau bowing gallantly to kiss the hand of a radiant Brigitte Bardot – one eye furtively seeks out the camera’s gaze. He is posed by Man Ray, displaying his beautiful hands; Cecil Beaton photographs him smoking opium, in a sepia haze. He is portrayed by Philippe Halsman as a god with six arms, bearing pen, book, cigarette, scissors: caught between versions of himself, he becomes Cocteaux. As if refracted by these multiple appearances, his person attains a strange, fugitive invisibility.

Eyes and gazes are everywhere in Cocteau’s work, from the devoted gaze of the lover in the lyric sequence Plain-chant (1923) to the uncanny eyes painted on the eyelids of Lee Miller in his 1930 film Le Sang d’un poète. He kept returning to the pivotal moment in the myth of Orpheus when a sudden, interlocked gaze sends Eurydice back to the unseen shades. Despite the connections, his work is remarkable for its eclecticism: he wrote poems, plays in verse, plays in prose, novels, memoirs; he devised writings in novel formats, which he sometimes illustrated. He made paintings and sculptures as well as stage sets, ballets, movies, ceramics. He ‘tattooed’ a villa, and several chapels. All this variety – this series of metamorphoses or, in his word, mues, ‘moultings’ – constitutes a kind of predicament, the tricks of a transformation artist always assuming different roles with a stealthy, virtuoso quickness parodically borne out in the syllables of his name: Cocteau – ‘coq-à-l’âne’, ‘coqs tôt’, ‘cocktail’. ‘There is something comic to surmount in your name,’ a director of the Revue blanche said to the young Cocteau in 1914, and his name was the source of jokes throughout his life, but he also had fun with the names of others: Marlene Dietrich’s, he said, ‘begins with a caress and ends with a horsewhip’. Through all his incarnations, Cocteau insisted, there runs the ‘blood of a poet’: he classified his works under the headings ‘poésie’, ‘poésie de théâtre’, ‘poésie critique’, ‘poésie de roman’, ‘poésie graphique’, ‘poésie cinématographique’. ‘To enclose the collected works of Jean Cocteau,’ Auden wrote, ‘one would need not a bookshelf, but a warehouse.’ It’s a double-edged remark: a warehouse is capacious but also a place for hiding things away. And yet Auden brings to light something of Cocteau’s fabulous theatricality: his collected works are like a vast, backstage world, where props and costumes are always magically available.

Claude Arnaud’s biography, first published in France more than ten years ago and now translated into English, describes a life that travels the distance from Proust to Bardot, not just chronologically but culturally, from Gallimard to the silver screen. The more time you spend with Cocteau the more Cocteaux appear: he’s an ambulance attendant in the First World War, tending the wounded alongside the patron of ballet Misia Sert, wearing a chic uniform designed by Poiret; he transforms himself from the ‘le prince frivole’ of the salons to hang out with the bohemians in Montparnasse but remains a boy living with his mother into his late thirties. He vanishes into opium dens, but then suddenly embarks on an impromptu trip around the world in eighty days. In another guise, he coaches the prizefighter Panama Al Brown. His desire to be noticed involves his revealing everything, but always in another set of clothes. In this he was like Coleridge, another opium addict, who found he could not ‘attain this innocent nakedness except by assumption. I resemble the Duchess of Kingston, who masqueraded in the character of “Eve before the Fall”, in flesh-coloured Silk.’ Ever visible, he drifts into other works of art: his cadences return in Pound’s Pisan Cantos; he appears as a blonde in a poem by Frank O’Hara; he becomes the name of a band, the Cocteau Twins. It’s as if he can beam into other worlds, as his voice does, through radio, in his 1950 film Orphée, transmitting from an elusive elsewhere.

Cocteau’s life, as Arnaud tells it, mirrors these fantastical thresholds by possessing what seems like an extraordinary double plot, as if there really were Cocteau twins: one zonked out on opium, the other incredibly prolific. His world is constructed like a revolving theatrical set: we are in the brothels of the Vieux Port of Marseille, then the scene suddenly shifts to the glamorous parties at Coco Chanel’s hôtel particulier on the rue Saint-Honoré; there is both high myth and low farce, decorum and kitsch, romance and smut. He was born in a wealthy suburb of Paris, Maisons-Laffitte, in 1889, into a prosperous Catholic family, a ‘bourgeois world’ where ‘we played tennis on one another’s courts.’ ‘Jean Cocteau loved his childhood,’ Arnaud writes, ‘as a country of its own’ with ‘secret rituals and magic spells’. He would conjure his mother in memory with Proustian adulation, as she dressed for the Opéra: ‘the adorable final rite that consisted of buttoning onto her wrist … the little keyhole opening of the glove where I would kiss her naked palm’. We spy through keyholes in all Cocteau’s work: here, a vista opens onto the past, to maman’s naked skin. But behind the propriety of glove buttons and tennis courts, a cousin whispers: ‘Listen, I know everything. There are big people that go to bed in the middle of the day. The men are called “jackrabbits”, the women “tarts” [cocottes]. Uncle André is a jackrabbit. If you repeat this, I’ll kill you with a spade.’

One day in April 1898 Cocteau’s father killed himself, for reasons that remain unclear. Between mother and child, throughout their entire abundant correspondence, not a word recalls this event. ‘Did mother and son secretly take advantage of the father’s disappearance?’ Arnaud asks. Cocteau became maman’s ‘little husband’. The handsome teenager would accompany Madame Cocteau to the salons. An uncanny physical resemblance between them, and the son’s financial dependence, contributed to a bond with a ‘conjugal air’. Given the looming figure of Oedipus and other paternal ghosts haunting Cocteau’s work, Arnaud speculates that he may have paid ‘with a secret guilt: as if he secretly held himself responsible for a disappearance that had opened up the favours of his mother exclusively to him’. Later in life, mother and son shared an apartment on the rue d’Anjou, with Madame Cocteau’s finely turned out sitting room, her Catholic conscience, a mere wall away from her son’s theatrical little den, adorned with masks, drawings, boys and, later, opium. When Picasso hurt Cocteau’s feelings by publishing some remarks describing his drawings as ‘pleasant’ and his writings as ‘journalistic’, it was to his mother he turned, like a petulant child: ‘If I have not thrown myself from the balcony it is because of you.’ Cocteau’s letters to her show the way mothers and children can fail to outgrow the composite identity they once possessed. ‘Rock me to sleep,’ he writes, ‘carry me as you carried me to my room, on the rue La Bruyère.’

Cocteau hated school and after he was expelled from the elite Lycée Condorcet, where Proust had studied, he set about creating a reputation for himself in Parisian society, publishing Le Prince frivole when he was still in his teens, and reading his poems aloud to the notorious Eduard de Max, while the actor reclined on a bed like a ‘fat Siamese cat curled up in the half-light among dirty cushions’. Proust thought of Cocteau as someone who nibbled marrons glacés all day and had no appetite left for real food. Cocteau, he understood, would waste his gifts thanks to his besotted socialising. (Cocteau later admitted that Proust knew ‘more than I about that future that everything hid from me’.) But they became friends. Trips to the Louvre followed, to see Mantegna’s Saint Sebastian, and soon Cocteau was visiting the boulevard Haussmann for readings from À la recherche du temps perdu. He would describe Marcel’s bedroom as ‘the first darkroom where I witnessed … the development of a powerful work’. The comparison recalls one of Proust’s own metaphors for intimacy: ‘Pleasures are like photographs: in the presence of the person we love, we take only negatives, which we develop later, at home, when we have at our disposal once more our inner darkroom, the door of which it is strictly forbidden to open while others are present.’ Cocteau was precociously impressive but he was also deeply impressionable.

One formative experience was the première of Le Sacre du printemps at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in 1913: the colours, the human bears performing primitive dances, the violent bursting forth of Russian spring, and – at the centre of it all – Nijinsky, who had leaped into Cocteau’s life a few years earlier, with ‘sylph-like grace’ and the ‘endurance of a muzhik’. He was to have a miserable end, but in Cocteau’s imagination he remained ‘half-angel, half-leopard’ and Arnaud suggests that most of Cocteau’s lovers ‘would have a savage, animalistic touch of Nijinsky about them’. The famous scandal of the ballet’s première was partly plotted by the ringmaster himself, Diaghilev. The audience laughed, booed, hissed; ladies cried out during the obscene dances, while, from the boxes, someone shouted: ‘Be quiet, you bourgeois bitches!’ Cocteau – like so many – was electrified. He would repudiate Le Prince frivole and his other early writings; he would give up the Symbolist haze of Anna de Noailles and be modern. He wanted to be part of the world of Apollinaire’s ‘Zone’, with its broken alexandrines and half-rhymes. His own effort to modernise himself took the shape of Le Cap de Bonne-Espérance, a poem he imagined would soar in its imitation of mechanised aerial flight but which hit Paris with a thud. This didn’t stop him staging numerous readings. The audience was disturbed by these uneven ‘verses’, which included ads for kub bouillon, byrrh aperitif and le petit journal. During one performance, as Cocteau was reading aloud from a notebook covered in his big purple writing, Proust came in – late, as usual. ‘Get out, Marcel, you’re spoiling my reading!’ Cocteau shouted.

At another reading, Cocteau was confronted by the haughty stare of a young soldier. ‘It’s very beautiful, don’t you think?’ Cocteau pleaded, speaking of his own poem; no reply. The soldier was André Breton. This was Cocteau’s first encounter with the Surrealist, who would direct a steady campaign of invective at Cocteau, in part homophobic, in part aimed at the excesses of the Right Bank. The animosity was never quite reciprocated by Cocteau, but the Surrealists’ loathing of him took on bizarre proportions when, in 1923, learning that he would be present at a dinner for Ezra Pound, Robert Desnos, author of Pénalités de l’enfer, turned up with the serious intention of killing Cocteau. In the end, his desired victim didn’t show up, and Desnos tried to plant his knife in Pound’s back; he was restrained and escorted out. The incident is one of the stranger threads linking Pound and Cocteau, artists who shared a tireless commitment to defending those contemporaries they believed to be important; by contrast, Breton’s way of forming a coterie seems like banditry.

In 1919 Cocteau met Raymond Radiguet, who was then 15. It was the first of many intense, transformative encounters with much younger men. Radiguet had already published stories, short plays and outlined a novel that would become Le Diable au corps. It’s not easy to grasp the charm of this myopic teenager in his long, dishevelled beaver coat; he was often surly and sometimes cruel, a combination that seems to have held a peculiar allure for Cocteau. Radiguet’s heterosexuality was a source of despair, as Monsieur Bébé (as Cocteau called him) paraded a string of girlfriends during wild nights at Le Boeuf sur le Toit. ‘When B. has sucked on his peppermint stick and made it sharp he will bury it in my heart,’ Cocteau complained, but both writers seemed to have found their collaboration productive – when Cocteau could persuade Radiguet not to drink a bottle of whisky a day. The writing flowed on their pastoral excursions away from Paris: Radiguet’s unattainable, naked body is the glowing centre around which Plain-chant turns. The pair began to change places in Cocteau’s mind. In conversation he attributed to Radiguet advice he’d given the boy; their ages became confused (‘Raymond was born at forty,’ Cocteau said; ‘Jean Cocteau will always be 18,’ said Radiguet).But, at twenty, Bébé died of typhoid fever. Coco Chanel and Misia Sert arranged a grand funeral – all in white, the colour for dead newborns. Cocteau vanished into grief. The former life and soul of the party at Le Boeuf sur le Toit was renamed ‘le veuf sur le toit’ by the gossip columnists. And opium entered his life.

Cocteau turned Radiguet into a kind of angel, an immortal youth who sometimes travelled under the mysterious name of ‘Heurtebise’, a name that came to him one day as he took the elevator up to Picasso’s studio on the rue La Boétie. ‘My name is on the plaque!’ a voice seemed to say to him: Heurtebise was the brand name of the mechanism lifting him up to heaven; it led him to produce ‘L’Ange Heurtebise’, a poem which, he said, was written automatically, under ‘dictation’. This mythic elevator would return in Orphée as the name for the personage capable of transporting the starring hunk, Jean Marais, up and down from the Underworld. With all his later lovers, Cocteau would find ways of retrieving Radiguet, or more; of Jean Desbordes, the first man to reciprocate his feelings, he said: ‘There has been a miracle from heaven – Raymond has returned in another form, and he often unmasks himself.’ More than anything he was in love with the indistinct end of childhood, when we can live most fully the myth and the crisis of what we might have it in ourselves to become. Adolescence, in this sense, is like opium, which ‘changes our speeds, procures for us a very clear awareness of worlds which are superimposed upon each other, which interpenetrate each other, and do not even suspect each other’s existence’.

Arnaud’s biography is full of scenes where individual and group histories intersect: his account of Occupied Paris, for instance, captures the eerie atmosphere of a city where clocks were set to German time. A literary biography deals in facts, but some of the pleasure of the form is in the palpable contrast between the world in which the subject lives, and the world as it appears for that subject. Biography presents a figure derived from, but not homologous with, a historical person. Part of the pathos of this, in Cocteau’s case, is his perpetual imagining of reality as semi-fictive, at once a source of pleasure in his life and one of its most fraught predicaments. ‘I wonder how a man can write the lives of the poets,’ he wrote, ‘since the poets themselves could not write their own. There are too many mysteries, too many true lies, too many tangled branches.’ Arnaud pays respect to Cocteau’s adulation of the unknown, which he set such store on leaving unexcavated, and yet he also has a sharp eye for the many discrepancies between Cocteau’s stories about himself and the facts as they appear to us, for the differences between life as his subject perceived it and the way things looked to others.

One such story is the mysterious year Cocteau claimed to have spent in Marseille as a boy. He had run away at 16, after a second failed attempt to pass the baccalaureate. He resolved to become a cabin boy, but found himself wandering the piers of the Vieux Port. An elderly Vietnamese woman picked him up off the rue de la Rose; he found work in a Chinese restaurant; he took refuge in a boys’ bordello, where he tried opium for the first time and lived for a year – or two, or four – using the papers of a young drowned man. Finally, two gendarmes took him back to Paris. Arnaud thinks the lack of any evidence, and his mother’s vigilance, make this escapade improbable. There is a parallel here with Walter Benjamin’s ‘Hashish in Marseille’ – the city seems to have had the cult status for the wandering bourgeois in search of experience that Berlin would have a hundred years later. Its port, its bars, its brothels are a theatrical setting for stories with narcotic twists. Marseille is part of Cocteau’s semi-fictive autobiography because he wanted this kind of rite of passage to matter for his life, as such transgressions and places of enigmatic suspension already mattered in his work.

The transitory space, the haunted hotel, both tawdry and elegant, is Cocteau’s best milieu; with its sense of suspended time, and the erotic proximity of strangers, the hotel, as he imagined it, is a temple to the pseudonymous, to disguise or transgression. In Le Sang d’un poète, a figure peeps through the keyholes of an establishment called the Hôtel des Folies Dramatiques: one scene shows a little girl being whipped by a stern matron; to the frustration of her punisher the child is able to levitate. Using Arnaud’s biography to look through the keyholes at the Hôtel Welcome, in Villefranche, where Cocteau stayed for extended periods, delivers another surprising sequence of real-life spectacles: Isadora Duncan wanders around barefoot looking for sailors, a basket of lobsters in her arms; Mary Butts is writing her books in a room upstairs; Cocteau moulds figurines of wax and pipe-cleaners in a room full of opium smoke. An American passing through wonders, innocently, at the smell that fills the hallways. Once Cocteau’s relationship with Desbordes and their mutual relationship with opium made living with Madame Cocteau impossible, he took up a nomadic existence. Hotels became places of refuge, stage sets that would be folded away: ‘I saw him living a false life, from hotel to hotel, from set to set,’ Cocteau said of Diaghilev, but he could have had his own life in mind, as he passed through a thousand furnished rooms.

Cocteau was a virtuoso of conversation. ‘The livest thing in Paris 1933 was Jean Cocteau,’ Pound wrote. ‘He talked, I should say, almost without interruption for two hours and over, with never a word that wouldn’t have been good reading.’ Less kindly, Gertrude Stein would say that ‘he spoke too well to ever write anything lasting.’ ‘Cocteau was very brilliant the last time we met,’ T.S. Eliot told Stravinsky, ‘but he seemed to be rehearsing for a more important occasion.’ It’s a remark that returns us to Cocteau’s fascination with a perpetual adolescence – the ongoing crisis of all the possible persons you might be. But it turns out that adolescence may not be something we can outgrow as readily as we think; our unlived lives can’t quite be destroyed like the pages of a teenage diary. Being haunted by the myth of your own potential may be an artistic privilege but it’s also a human predicament, and Cocteau felt it in a more menacing way than most. ‘I’ve dreamed more than I’ve lived and it has taken on terrible proportions. The spectator can barely notice that I’m like an actor in someone else’s play. And even this other is under orders from a mysterious schizophrenic who lives in us all, that most people manage to exorcise, or in whom they refuse to believe.’

As Cocteau aged, he became, as Arnaud puts it, a ‘sad clown of modernity’: both a ‘young man lost in old age’ and ‘an old man imprisoned by youth’, wearing a little cap and striped sailor’s shirt, ‘like Popeye without his spinach’. ‘Sometimes, you can still meet in Paris people who knew Cocteau,’ Arnaud’s book ends. ‘You will recognise them by their way of opening their doors wide, by their warm, knowing voices, and by the happiness they feel in introducing you to someone who will perhaps leave their mark on your life.’ This, Arnaud writes, ‘is what happened to me in 1977, and life changed for ever and for the better. I was no longer the same, after this encounter; it was as if Cocteau had indirectly put a spell on me.’ Cocteau enjoyed working in collaboration, bringing relations into being: relations between art forms, and between persons. Inevitably, collaboration – and conversation, the sharing of creative practice – leaves a different kind of trace from that of the solitary ego who stakes out his territory in print. Stein’s caricature – ‘he spoke too well to ever write anything lasting’ – tells only half the story. Auden wrote that the ‘lasting feeling’ Cocteau’s ‘work leaves is one of happiness, not, of course, in the sense that it excludes suffering, but because, in it, nothing is rejected, resented or regretted.’ This sense of possibility is captured by his epitaph in Saint-Blaise des Simples, the little chapel he decorated: ‘Je reste avec vous.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.