In 1915 Charlotte Perkins Gilman published a funny but unsettling story called Herland. As the title hints, it’s a fantasy about a nation of women – and women only – that has existed for two thousand years in some remote, still unexplored part of the globe. A magnificent utopia: clean and tidy, collaborative, peaceful (even the cats have stopped killing the birds), brilliantly organised in everything from its sustainable agriculture and delicious food to its social services and education. And it all depends on one miraculous innovation. At the very beginning of its history, the founding mothers had somehow perfected the technique of parthenogenesis. The practical details are a bit unclear, but the women somehow just gave birth to baby girls, with no intervention from men at all. There was no sex in Herland.

The story is all about the disruption of this world when three American males discover it: Vandyck Jennings, the nice-guy narrator; Jeff Margrave, a man whose gallantry is almost the undoing of him in the face of all these ladies; and the truly appalling Terry Nicholson. When they first arrive, Terry refuses to believe that there aren’t some men around somewhere, pulling the strings – because how, after all, could you imagine women running anything? When eventually he has to accept that this is exactly what they are doing, he decides that what Herland needs is a bit of sex and a bit of male mastery. The story ends with Terry unceremoniously deported after one of his bids for mastery, in the bedroom, goes horribly wrong.

There are all kinds of irony to this tale. One joke that Perkins Gilman plays throughout is that the women simply don’t recognise their own achievements. They have independently created an exemplary state, one to be proud of, but when confronted by their three uninvited male visitors, who lie somewhere on the spectrum between spineless and scumbag, they tend to defer to the men’s competence, knowledge and expertise; and they are slightly in awe of the male world outside. Although they have made a utopia, they think they have messed it all up.

As well as describing imaginary communities of women doing things their way, Herland raises bigger questions, from knowing how to recognise female power to the sometimes funny, sometimes frightening stories we tell ourselves about it, and indeed have told ourselves about it, in the West at least, for thousands of years.

I’ve talked before about the ways women get silenced in public discourse. And there’s plenty of that silencing still going on. We need only think of Elizabeth Warren being prevented a few weeks ago from reading out a letter by Coretta Scott King in the US Senate.1 What was extraordinary on that occasion wasn’t only that she was silenced and formally excluded from the debate (I don’t know enough about the rules of procedure in the Senate to have a sense of how justified, or not, that was); but that several men over the next couple of days did read the letter out and were neither excluded nor shut up. True, they were trying to support Warren. But the rules of speech that applied to her didn’t appear to apply to Bernie Sanders, or the three other male senators who did the same.

The right to be heard is crucially important. But I want to think more generally about how we have learned to look at women who exercise power, or try to; I want to explore the cultural underpinnings of misogyny in politics or the workplace, and its forms (what kind of misogyny, aimed at what or whom, using what words or images, and with what effects); and I want to think harder about how and why the conventional definitions of ‘power’ (or for that matter of ‘knowledge’, ‘expertise’ and ‘authority’) that we carry round in our heads have tended to exclude women.

It is happily the case that in 2017 there are more women in what we would all probably agree are ‘powerful’ positions than there were ten, let alone fifty years ago. Whether that is as politicians, police commissioners, CEOs, judges or whatever, it’s still a clear minority – but there are more. (If you want some figures, around 4 per cent of UK MPs were women in the 1970s; around 30 per cent are now.) But my basic premise is that our mental, cultural template for a powerful person remains resolutely male. If we close our eyes and try to conjure up the image of a president or (to move into the knowledge economy) a professor, what most of us see isn’t a woman. And that’s just as true even if you are a woman professor: the cultural stereotype is so strong that, at the level of those close-your-eyes fantasies, it is still hard for me to imagine me, or someone like me, in my role. I put the phrase ‘cartoon professor’ into Google Images – ‘cartoon professor’ to make sure that I was targeting the imaginary ones, the cultural template, not the real ones. Out of the first hundred that came up, only one, Professor Holly from Pokémon Farm, was female.2

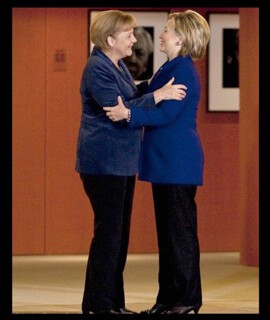

To put this the other way round, we have no template for what a powerful woman looks like, except that she looks rather like a man. The regulation trouser suits, or at least the trousers, worn by so many Western female political leaders, from Merkel to Clinton, may be convenient and practical; they may be a signal of the refusal to become a clothes horse, which is the fate of so many political wives; but they’re also a simple tactic – like lowering the timbre of the voice – to make the female appear more male, to fit the part of power.3 Elizabeth I knew exactly what the game was when she said she had ‘the heart and stomach of a king’. It’s that idea of the divorce between women and power that makes Melissa McCarthy’s parodies of the White House press secretary Sean Spicer on Saturday Night Live so effective. It’s said that these have annoyed President Trump more than most satires on his regime, because (according to one of the ‘sources close to him’), ‘he doesn’t like his people to appear weak.’ Decode that, and what it actually means is that he doesn’t like his men to be parodied by and as women. Weakness comes with a female gender.4

What follows from this is that women are still perceived as belonging outside power. Whether we sincerely want them to get to the inside of it or whether, by various often unconscious means, we cast women as interlopers when they make it (I still remember a Cambridge where, in most colleges, the women’s loos were tucked away across two courts, through the passage and down the stairs in the basement), the shared metaphors we use of female access to power – knocking on the door, storming the citadel, smashing the glass ceiling, or just giving them a leg up – underline female exteriority. Women in power are seen as breaking down barriers, or alternatively as taking something to which they are not quite entitled. A headline in the Times in early January captured this wonderfully. Above an article reporting on the possibility that women might soon gain the positions of Metropolitan Police commissioner, chair of the BBC Trust, and bishop of London, it read: ‘Women Prepare for a Power Grab in Church, Police and BBC.’ (Cressida Dick, the new commissioner of the Met, is the only one of these predictions yet to have come true.) Now, I realise that headline writers are paid to grab attention. But the idea that even under those circumstances you could present the prospect of a woman becoming bishop of London as a ‘power grab’ (and that probably thousands upon thousands of readers didn’t bat an eyelid when they read it) is a sure sign that we need to look a lot more carefully at our cultural assumptions about women’s relationship with power. Workplace nurseries, family-friendly hours, mentoring schemes and all those practical things are importantly enabling, but they are only part of what we need to be doing. If we want to give women as a gender – and not just in the shape of a few determined individuals – their place on the inside of the structures of power, we have to think harder about how and why we think as we do. If there is a cultural template, which works to disempower women, what exactly is it and where do we get it from?

At this point, it may be useful to start thinking about the classical world. More often than we may realise, and in sometimes quite shocking ways, we are still using Greek idioms to represent the idea of women in, and out of, power. There is at first sight a rather impressive array of powerful female characters in the repertoire of Greek myth and storytelling. In real life, ancient women had no formal political rights, and precious little economic or social independence; in some cities, such as Athens, respectable married women were almost never seen outside the home. But Athenian drama in particular, and the Greek imagination more generally, has offered our imaginations a series of unforgettable women: Medea, Clytemnestra, Antigone.

They are not, however, role models – far from it. For the most part, they are portrayed as abusers rather than users of power. They take it illegitimately, in a way that leads to chaos, to the fracture of the state, to death and destruction. They are monstrous hybrids, who aren’t – in the Greek sense – women at all. And the unflinching logic of their stories is that they must be disempowered, put back in their place. In fact, it is the unquestionable mess that women make of power in Greek myth that justifies their exclusion from it in real life, and justifies the rule of men. (I can’t help thinking that Perkins Gilman was lightly parodying this logic when she made the women of Herland believe that they had messed up.)

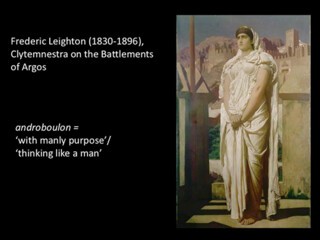

Go back to one of the very earliest Greek dramas to survive, the Agamemnon of Aeschylus, first performed in 458 bc, and you’ll find that its antiheroine, Clytemnestra, horribly encapsulates that ideology. In the play, she becomes the effective ruler of her city while her husband is away fighting the Trojan War; and in the process she ceases to be a woman. Aeschylus repeatedly uses male terms and the language of masculinity to refer to her. In the very first lines, for example, her character is described as androboulon – a hard word to translate neatly but something like ‘with manly purpose’, or ‘thinking like a man’. And, of course, the power that Clytemnestra illegitimately claims is put to destructive purpose when she murders Agamemnon in his bath on his return. The patriarchal order is only restored when Clytemnestra’s children conspire to kill her.5

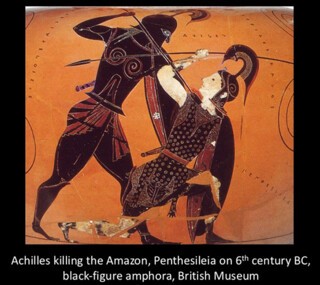

There’s a similar logic in the stories of that mythical race of Amazon women, said by Greek writers to exist somewhere on the northern borders of their world.6 A more violent and more militaristic lot than the peaceful denizens of Herland, this monstrous regiment always threatened to overrun the civilised world of Greece and Greek men. An enormous amount of modern feminist energy has been wasted on trying to prove that these Amazons did once exist, with all the seductive possibilities of a historical society that really was ruled by and for women. Dream on. The hard truth is that the Amazons were a Greek male myth. The basic message was that the only good Amazon was a dead one, or – to go to back to awful Terry – one that had been mastered, in the bedroom. The underlying point was that it was the duty of men to save civilisation from the rule of women.7

There are, it is true, occasional examples where it might look as if we are getting a more positive version of ancient female power. One staple of the modern stage is Aristophanes’ comedy known by the name of its lead female character, Lysistrata. Written in the fifth century bc, it appears to be a perfect mixture of highbrow classics, feisty feminism, a stop-the-war agenda and a good sprinkling of smut (and it was once translated by Germaine Greer). It’s the story of a sex-strike, set not in the world of myth but in the contemporary world of ancient Athens. Under Lysistrata’s leadership, the women try to force their husbands to end the long-running war with Sparta by refusing to sleep with them until they do. The men go round for most of the play with enormously inconvenient erections (which now tends to cause some difficulty and hilarity in the costume department). Eventually, unable to bear their encumbrances any longer, they give in to the women’s demands and make peace. Girl power at its finest, you might think.8

Athena, the patron deity of the city, is often brought in on the positive side too. Doesn’t the simple fact that she was female suggest a more nuanced version of the imagined sphere of women’s influence? I’m afraid not.

If you scratch the surface and go back to the fifth-century context, Lysistrata looks very different. It’s not just that the original audience and actors consisted, according to Athenian convention, entirely of men – the female characters were probably played much like pantomime dames. It’s also the fact that, in the end, the fantasy of women’s power is firmly stamped down. In the final scene, the peace process consists of bringing a naked woman onto the stage (or a man somehow dressed up as a naked woman), who is used as if she were a map of Greece, and is metaphorically carved up in an uncomfortably pornographic way between the men of Athens and Sparta. Not much proto-feminism there.

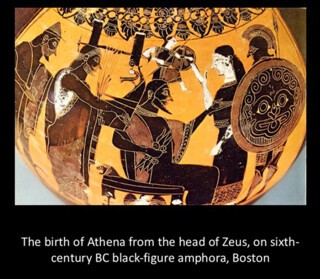

As for Athena, it’s true that in those binary charts of gods and goddesses that we make for ourselves, she appears on the female side. But the crucial thing about her in the ancient context is that she is another of those difficult hybrids. In the Greek sense she’s not a woman at all. For a start she’s dressed as a warrior, when fighting was exclusively male work (that’s an underlying problem with the Amazons too). Then she’s a virgin, when the raison d’être of the female sex was breeding new citizens. And she wasn’t even born of a mother but directly from the head of her father, Zeus. It was almost as if Athena, woman or not, offered a glimpse of an ideal male world in which women could not just be kept in their place but dispensed with entirely.9

The point is simple but important: if we go back to the beginnings of Western history we find a radical separation – real, cultural and imaginary – between women and power. But one item of Athena’s costume brings this right up to our own day. On most images of the goddess, at the very centre of her body armour, fixed onto her breastplate, is the image of a female head, with writhing snakes for hair. This is the head of Medusa, one of three mythical sisters known as the Gorgons, and it was one of the most potent ancient symbols of male mastery of the dangers that the very possibility of female power represented. It’s no accident that we find her decapitated, her head proudly paraded as an accessory by this decidedly un-female female deity.

There are many ancient variations on Medusa’s story. One famous version has her as a beautiful woman raped by Poseidon in a temple of Athena, who promptly transformed her, as punishment for the sacrilege, into a monstrous creature with a deadly capacity to turn to stone anyone who looked at her face. It later became the task of the hero Perseus to kill this woman, and he cut her head off using his shiny shield as a mirror so as to avoid having to look directly at her. At first he used the head as a weapon since – even in death – it retained the capacity to petrify; but he then presented it to Athena, who displayed it on her own armour (one message being: take care not to look too directly at the goddess).10

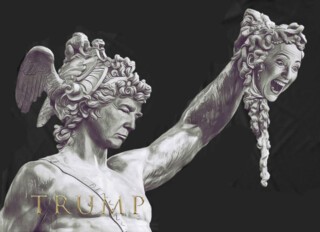

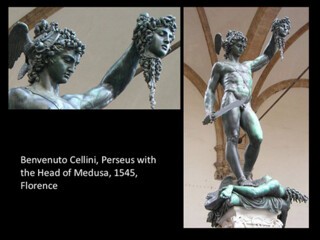

It doesn’t need Freud to see those snaky locks as an implied claim to phallic power. This is the classic myth in which the dominance of the male is violently reasserted against the illegitimate power of the woman. And Western literature, culture and art have repeatedly returned to it in those terms. The bleeding head of Medusa is a familiar sight among our own modern masterpieces, often loaded with questions about the power of the artist to represent an object at which no one should look. In 1598 Caravaggio did an extraordinary version of the decapitated head with his own features, so it is said, screaming in horror, blood pouring out, the snakes still writhing. A few decades earlier Cellini made a large bronze statue of Perseus which still stands in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence: the hero is depicted trampling on the mangled corpse of Medusa, and holding her head up in the air, again with the blood and the gunge pouring out of it.11

What’s extraordinary is that this beheading remains even now a cultural symbol of opposition to women’s power. Angela Merkel’s features have again and again been superimposed on Caravaggio’s image.12 In one of the more silly outbursts in this vein, a column in the magazine of the Police Federation called Theresa May the ‘Medusa of Maidenhead’ during her time as home secretary. ‘The Medusa comparison might be a bit strong,’ the Daily Express responded: ‘We all know that Mrs May has beautifully coiffed hair.’ But May got off lightly compared with Dilma Rousseff, who had to open a major Caravaggio show in São Paolo. The Medusa was naturally in it, and Rousseff standing in front of the very painting proved an irresistible photo opportunity.

But it’s with Hillary Clinton that we see the Medusa theme at its starkest and nastiest. Predictably Trump’s supporters produced a great number of images showing her with snaky locks. But the most horribly memorable of them adapted Cellini’s bronze, a much better fit than the Caravaggio because it wasn’t just a head: it also included the heroic male adversary and killer. All you needed to do was superimpose Trump’s face on that of Perseus, and give Clinton’s features to the severed head (in the interests of taste, I guess, the mangled body on which Perseus tramples in the original was omitted). It’s true that if you crawl around some of the darker recesses of the web, you can find some very unpleasant images of Obama, but they’re very dark recesses. This scene of Perseus-Trump brandishing the dripping, oozing head of Medusa-Clinton was very much part of the everyday, domestic American decorative world: you could buy it on T-shirts and tank tops, on coffee mugs, on laptop sleeves and tote bags (sometimes with the logo triumph, sometimes trump). It may take a moment or two to take in that normalisation of gendered violence, but if you were ever doubtful about the extent to which the exclusion of women from power is culturally embedded or unsure of the continued strength of classical ways of formulating and justifying it – well, I give you Trump and Clinton, Perseus and Medusa, and rest my case.

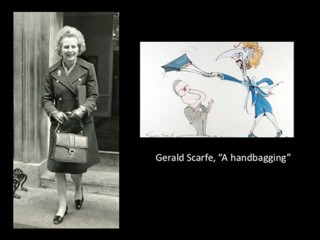

It isn’t enough to rest the case there without saying what we might actually do. What would it take to resituate women on the inside of power? Here I think we have to distinguish between an individual perspective and a more communal, general one. If we look at some of the women who have ‘made it’, we can see that the tactics and strategies behind their success don’t merely come down to aping male idioms. One thing that many of these women share is a capacity to turn the symbols that usually disempower women to their own advantage. Margaret Thatcher seems to have done that with her handbags, so that eventually the most stereotypically female accessory became a verb of political power: as in ‘to handbag’.13 And I suppose that at an incomparably more junior level I did something similar when I went for my first interview for an academic job, in Thatcher’s heyday as it happens. I bought a pair of blue tights specially for the occasion. It wasn’t my usual fashion choice, but the logic was satisfying: ‘If you interviewers are going to be thinking that I’m a right bluestocking, let me just show you that I know that’s what you’re thinking and that I got there first.’

As for Theresa May, it may be a bit too early to say, and there is a possibility that we will end up looking back to her as a woman who was put into power in order to fail. (I’m trying very hard here not to compare her to Clytemnestra.) But I do sense that her ‘shoe thing’ and those kitten heels are one of the ways she shows that she is refusing to be packaged into the male template. She is also rather good, as Thatcher was, at exploiting the weak spots in the armoury of traditional Tory male power. The fact that she isn’t part of the clubbable boys’ world, that she isn’t ‘one of the lads’, has helped her carve out independent territory for herself. She has gained power and freedom out of the exclusion. She is also allergic to ‘mansplaining’.

Many women could, I’m sure, share perspectives and tricks like this. But the big issues I’ve been trying to confront aren’t solved by tips on how to exploit the status quo. And I don’t think patience is likely to be the answer either, though gradual change very likely will take place. In fact, given that women in this country have only had the vote for a hundred years, we shouldn’t forget to congratulate ourselves for the revolution that we have all, women and men, brought about. That said, if the deep cultural structures legitimating women’s exclusion are as I have argued, gradualism is likely to take too long for me, thank you very much. We have to be more reflective about what power is, what it is for, and how it is measured. To put it another way, if women aren’t perceived to be fully within the structures of power, isn’t it power that we need to redefine rather than women?

So far the women’s power I’ve been referring to is the usual kind we imagine, possessed by national politicians, CEOs, prominent journalists, television executives and so on. This gives a very narrow version of what power is, largely correlating it with public prestige (or in some cases public notoriety). It’s very ‘high end’ in a very traditional sense, and bound up with the ‘glass ceiling’ image of power, which not only effectively positions women on the outside of power, but also imagines the female pioneer as the already successful superwoman with just a few last vestiges of male prejudice keeping her from the top. I don’t think this model speaks to most women, who even if they aren’t aiming to be president of the US or a company boss, still rightly feel that they want a stake in power. And it certainly didn’t appeal last year to sufficient numbers of American voters.

Even if we do restrict our sights to national politics the question of the way we judge women’s success within it is tricky. There are plenty of league tables charting the proportion of women within national legislatures. At the very top comes Rwanda, where more than 60 per cent of the members of the legislature are women, while the UK is almost fifty places down, at roughly 30 per cent. Strikingly, the Saudi Arabian National Council has a higher proportion of women than the US Congress. It’s hard not to lament some of these figures and applaud others, and a lot has rightly been made of the role of women in post-civil war Rwanda. But I do wonder if, in some places, the presence of large numbers of women in the national legislature means that that is where the power is not.

I’m also not sure that we’re being quite straight with ourselves about what we want women in parliaments for. A number of studies point to the role of women politicians in promoting legislation in women’s interests (in childcare, for example, equal pay and domestic violence). A report from the Fawcett Society recently suggested a link between the 50/50 balance between women and men in the Welsh Assembly and the number of times ‘women’s issues’ were raised there. I’m certainly not going to complain about childcare and the rest getting a fair airing, but I’m not sure it’s a good idea that such things continue to be perceived as ‘women’s issues’, and – for me at least – they aren’t the main reasons we want more women in parliaments. Those reasons are much more basic: it is flagrantly unjust to keep women out, by whatever unconscious means we do so; and we simply can’t afford to do without women’s expertise, whether it is in technology, the economy or social care. If that means fewer men get into the legislature, as it must do (social change always has its losers as well as its winners), I’m happy to look those men in the eye.

But this is still treating power as an elite thing, coupled to public prestige, to the individual charisma of so-called ‘leadership’, and often, though not always, to a degree of celebrity. It’s also treating power very narrowly as something only the few – mostly men – can possess or wield (that’s exactly what’s summed up by the image of Perseus or Trump, brandishing his sword). On those terms, women as a gender – not as some individuals – are by definition excluded from it. You can’t easily fit women into a structure that is already coded as male; you have to change the structure. That means thinking about power differently. It means decoupling it from public prestige. It means thinking collaboratively, about the power of followers not just of leaders. It means above all thinking about power as an attribute or even a verb (‘to power’), not as a possession: what I have in mind is the ability to be effective, to make a difference in the world, and the right to be taken seriously, together as much as individually. It’s power in that sense that many women feel they don’t have – and that they want. Why the popular resonance of ‘mansplaining’ (despite the intense dislike of the term felt by many men)? It hits home for us because it points straight to what it feels like not to be taken seriously: a bit like when I get lectured on Roman history on Twitter.

So should we be optimistic about change when we think about what power is and what it can do, and women’s engagement with it? Maybe, we should be a little. I’m struck, for example, that one of the most influential political movements of the last few years, Black Lives Matter, was founded by three women; few of us, I suspect, would recognise any of their names, but together they had the power to get things done in a different way.14

I’m not sure that culturally we’ve got anywhere near subverting those foundational stories of power that serve to keep women out of it, and turning them to our own advantage, as Thatcher did with her handbag. I have been playing the part of the pedant, objecting to Lysistrata being played as if it were about girl power (maybe that’s exactly what we should be doing). There have been all kinds of well-known feminist attempts over the last fifty years or more to reclaim Medusa for female power (‘Laugh with Medusa’, as the title of one recent collection of essays almost put it) – not to mention the use of her as the Versace logo – but it’s made not a blind bit of difference to the way she has been used in attacks on female politicians.

The power of those traditional narratives is very nicely, though fatalistically, captured by Perkins Gilman. There is a sequel to Herland, in which Vandyck decides to escort Terry back home to Ourland, taking with him his wife from Herland, Ellador: it’s called With Her in Ourland. In truth, Ourland doesn’t show itself off very well, not least because Ellador is introduced to it in the middle of World War One. And before long the couple, having ditched Terry, decide to go back to Herland. By now Van and Ellador are expecting a baby, and – you may have guessed it – the last words of this second novella are: ‘In due time a son was born to us.’ Perkins Gilman must have been well aware that there was no need for another sequel. Any reader in tune with the logic of the Western tradition would have been able to predict exactly who would be in charge of Herland in fifty years’ time. That boy.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.