The most recent of William Kentridge’s works on display in Thick Time at the Whitechapel Gallery (until 15 January) is called Right into Her Arms. It’s also one of the best. A raised stage, three metres long, about a metre high, is dressed with a flimsy backdrop of beige, brown, grey; here and there are torn swatches of yellow, green and maroon. At first we seem to see an austere Kurt Schwitters collage from the early 1920s. Close up, we discover unadorned cardboard, plain or coloured card. The wings of the stage are decorated with pages from a dictionary. Front of stage are two rectangular, mobile panels, MDF or cork, decorated like the rest and attached to a guide rail that runs along the top of the proscenium. They are driven left and right by an electric motor, or angled, or made to pirouette through 360 degrees. Mostly they trundle to and fro; on occasion they whizz or flounce; once or twice they cross.

The show, which lasts 11 minutes, consists of a recorded montage of images, still and moving, beamed onto this protean set from a projector: ink splashes, ink and charcoal drawings, fragments of libretto and video outtakes, all retrieved from the workshop of ideas, materials and players that Kentridge put together for his production of Lulu, performed at the Met last year and coming to ENO on 9 November. Right into Her Arms restages the conception, design and history of the production as a kinetic notebook, full of surprise and comedy. As the panels go this way and that, the projected images are refracted across two, sometimes three planes. The little play reaches its climax over a soundtrack of Webern and Schoenberg and a recital by Kentridge of passages from Schwitters’s sound poem Ursonate. At that point we’ve begun to realise that the panels are no longer backdrops but ungainly understudies, doing their best to rehearse the torment of the opera’s characters.

All the Kentridge hallmarks are on this piece. The references to early 20th-century modernism that announce his loves and loyalties. The celebration of old, pre-wireless technologies and mechanical motion: we see clumsy loops of cable on the floor, scrawls of wiring, an overhead rig driving the panels back and forth. The presence of the artist in the work: a brief sequence shows Kentridge’s fingers on the brush as it launches a flurry of ink and then retires from view. The gentle reminder that a new work by Kentridge – even a new exhibition like Thick Time – is always a retrospective: he likes to revisit the sites of earlier victories and re-enact them as if the outcome still remained to be seen. There’s also his democratic surrender of drawing, along with its fine-art credentials, to HD video animation as one element in a rich, mixed-media assembly. Finally there’s the gag: the edgy sense of fun in Kentridge is never far from silent comedy, or the early talkie features, where disguise, desire and misunderstanding drive the laughs, along with the pathos. (Kentridge directed a production of The Magic Flute in 2005, but could just as well have done a Marriage of Figaro or Così Fan Tutte.) Animating physical objects is funny, and harder than making stop-motion sequences from great drawings. An artist who can bring two rectangles of wood to life as dramatis personae in a vexing modernist opera could probably animate an insurance policy.

Kentridge grew up in apartheid South Africa. His parents were lawyers: Sydney acted for regime opponents, including Mandela, and for their relatives, including Steve Biko’s family after he was murdered in custody; Felicia was one of the founders of the Legal Resources Centre, providing support inside and outside the courts for poor South Africans and campaigning against the pass laws. Apartheid is a lurking presence in a number of Kentridge’s prints and drawings, but so is the grime and oppression of an industrialised economy on the southern tip of Africa. In Kentridge the Afrikaner ascendancy is a moment in a longer history, which continues beyond apartheid: he is fascinated by colonialism and industrialisation, and the encounters they continue to produce between alien cultures that have yet to resolve their differences.

In The Refusal of Time (2012), a 30-minute piece with music, ‘soundscape’ and a five-channel video projection, empire-era maps appear with the names of anti-colonial revolts flagged up: the Herero rebellion in Namibia, for instance, and the Bambatha revolt in South Africa. Do we package up these episodes simply by naming and dating them? The notion, for the purposes of this piece, is that they persist in non-chronological time – the kind Kentridge wants us to think about. The Refusal of Time was inspired, in part, by his discussions with Peter Galison, a Harvard physicist and historian of science. Galison wrote a witty, difficult text to accompany the piece on its first outing in Kassel, but if you imagine time as a container ship of inconceivable dimensions filling up with endless cargo, you’re roughly on the right track. Or, as the soundtrack says, ‘a universal archive’: an expanding hulk loaded with containerised traces of what we did, who we were, perhaps even what we thought, all of it destined to hang around as carbon dust or glowing embers, or minuscule slivers of ice.

There is no ‘progress’ in this model, but there can be forward movement, and circular motion. In The Refusal of Time this is represented as a kind of dance: a procession of the downtrodden, clearly African, projected onto three walls of the gallery. The room is spacious and so the cortège of silhouettes following itself around the walls, through a shadowy Kentridge landscape reminiscent of the industrial sprawl beyond Johannesburg, achieves an impressive scale. Weary yet somehow rolling with the pace, these are the labouring poor, hewers of wood and drawers of water, adults and children carrying shovels, megaphones, odds and ends that might have been ripped from a miners’ ablution block – old showerheads, a tub – and arcane mechanical parts, suggesting bits of pithead gear. But why do we associate their wretchedness with the passion for counting and calibrating that drove the great advances of the industrial era? In a jokey reference to time-and-motion studies from the 1950s, two figures operating a handcar are also rotating the hands of an analogue clock. Yet for all its drudgery, the procession is seditious, menacing, propelled by a wild music – part carnivalesque, part dirge (Philip Miller is the composer) – and by the moves of a jubilant dancer, in silhouette like the rest of the troupe.

Elsewhere in the piece, we’re asked to think about time as if it weren’t the thing we experience. That’s not easy: just as ideas about the materiality of the sign are mostly expressed in the medium they’re investigating, Kentridge’s exploration can only unfold in tick-tock time. But it’s cleverly disruptive. In the overture, giant metronomes are shown marking the same beat; when they kick out of sync, it’s like a jolt to the body. Later we watch a filmed double-act starring two Kentridges; one of him leaves the studio and the other remains behind. I’m unsure of my ground here, but the reference is surely to Einstein’s famous twins, one of whom leaves for space, and ages less rapidly than the other, who stays at home. In Galison’s text, Einstein’s scientific twin is Friedrich Adler, a close friend and, like Einstein, a disciple of Ernst Mach. We’re left wondering whether Adler, who assassinated the Austrian ‘minister-president’ Karl von Stürgkh in Vienna in 1916, aged more quickly during his brief jail term than Einstein, who was rocketing round the German science academies at the time.

In the middle of the gallery an imposing contraption raises and lowers embossed catflaps on wooden rods, to the rhythmic sound of a bellows. It’s billed as a ‘breathing machine’, but Kentridge and his collaborators call it ‘the elephant’. Part of its purpose is to make us think about the place of monotony in the age of coal and steam, standardised measures of time, weight and distance, and the hunger for precision, which reaches a weird apogee, for Kentridge, with the arrival of pneumatic timekeeping in the 1880s in Paris. But the contraption also reminds us of the human body measuring out a life by breaths (eight or nine million breaths a year): not the gusts of compressed air that drove the minute hands on thousands of Parisian clocks to the next graduation, but a single breath as a sign of life. We turn our gaze from the ungainly, puffing elephant to the images on the walls – of tuba players, trombonists, figures with megaphones to their mouths – and realise, with a sigh of relief, that breath is also a precondition of music and speech.

Much of this is paradoxical, or would be if Kentridge were making an argument. In fact he is rearranging sets of ideas, often by intuition, like objects turned out of a box. The results are deeply satisfying, even if we’re left to order our own thoughts. What he once said of animated film holds for the eclectic montages in this piece: they are ‘a demonstration of how we make sense of the world, rather than an instruction about what the world means’. While his breathing machine toils on, heroically uninstructed, at the centre of the room, we have begun to grasp that we exist in a timescape where nothing is ever fully erased: the worldwide web is more than just an analogy; it’s evidence that this vast repository of doings and sayings may actually exist. On the soundtrack Kentridge wonders how to ‘undo, unsay, unremember’, make things ‘unhappen’ – a question, perhaps, about how to live with the endless dissemination of one’s life in the chamber of everything. We hear his voice repeating, ‘Here I am,’ as if he longed to stay put and age normally, in a well-defined space with walls, a floor and a ceiling.

That place is the artist’s studio, the setting for nine short films, made in 2003 – Day for Night, Journey to the Moon and 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès – all projected in a large room upstairs at the Whitechapel. Shot on 16 and 35 mm film and edited in video by his colleague Catherine Meyburgh, the fragments turn the studio into a magician’s den. Stop-motion and reverse-motion produce bizarre effects as Kentridge is shown drawing, erasing, reinscribing – sometimes a line inscribes or reinstates itself – on sheets of paper. A damaged life-size portrait is repaired and reassembled; writing is sucked off the page and into the nib of a pen; new work ingests earlier work and everything is up for revision. Kentridge paces and gestures like a silent movie actor (Soviet cinema now, not Keystone studios); he returns to the desk and the artist’s materials perform at his bidding.

The great piece in this room is an idiosyncratic ‘remake’ of Le Voyage dans la lune, Méliès’s most famous film, from 1902. In Kentridge’s version the artist takes off from his studio by converting an Italian stove-top coffee-maker into a rocket. On touchdown he gazes out at what might be a stretch of unreclaimable ground at the back of a mine dump. Inside the little macchinetta spacecraft a nude figure – his wife – approaches him from behind and lays a hand on his back, as he gazes through the window. He reaches over his shoulder to put his hand on hers, but she’s gone. Outside, ragged, defiant figures make their way across the broken ground: the wretched of the moon.

In South Africa, a highly capitalised economy, mainstream opposition to apartheid took the form of class struggle, not race war, and Kentridge is fascinated both by the failures of the Russian Revolution and the successes of revolutionary avant-gardism. A dazzling multi-channel video collaboration with Miller and Meyburgh from 2008, I am not me, the horse is not mine, reimagines Stalin’s assault on Soviet modernism in the 1930s. At the Whitechapel, a more recent, five-channel video installation uses a recording of a speech in French that Trotsky was rehearsing at the time of his exile in Turkey, film footage of Trotsky, a comic appearance by Kentridge as Trotsky, and a perplexing slapstick vignette which may or may not be a day in the life of his secretary, Evgenia Shelepina. The title, O Sentimental Machine, plays with the notion – here ascribed to Trotsky himself – that humans are ‘sentimental but programmable machines’, but it’s soon apparent that the Shelepina figure is having trouble conforming to the programme. The waters of the Bosphorus seem to rise and subside around the figure of Trotsky in the film footage. Amid the mounting anarchy, the secretary does a routine in front of a full-length mirror, reminding us that Duck Soup was released in the same year – 1933 – as the speech was being rehearsed. This is a frustrating piece, unfinished but hardly open-ended; it has an awkward surrealist manner, unusual in Kentridge, whose theatrical surprises and metamorphoses are closer to the older French tradition of féerie.

Recent Kentridge pieces can achieve a reassuring lightness that was not always there in the earlier work. His run of animated films featuring Soho Eckstein, the capitalist, and Felix Teitelbaum, the thoughtful melancholic, made in the closing stages of apartheid, caught the sombre mood of the times; the draughtsmanship invited comparisons with Goya and – more to the point – Käthe Kollwitz: exhausted labourers, workforce dormitories, the rockface and the sparkling drill bit. Eckstein’s own surroundings were full of sinister clutter: mechanical cash registers and bakelite phones that morphed into cats. On his breakfast tray in Mine (1991) there’s a demonic cafetière: when he pushes down the plunger it goes clean through the pot, the building, the ground, boring deep into the world populated by his workers. But there were little feats of reclamation in these sooty films. In Felix in Exile (1994), Kentridge handles the victims of the township wars, fought in the run-up to Mandela’s victory at the polls, with ritual care. The body on the ground whose head the family has just covered with a newspaper is a typical sight to be ‘unremembered’, as far as I’m concerned (I was working in the townships at the time). But watching the film recently on DVD, the unsentimental kindness of the artist’s eye, as it mourned the dead, felt to me like a prompt to ‘unforget’.

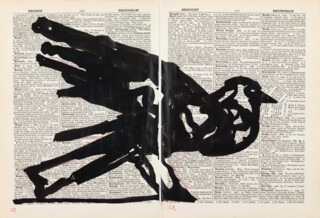

Kentridge’s reclamation work goes on. In Accounts and Drawings from Underground (2015), a collaboration with the anthropologist Rosalind Morris, he has drawn forty landscapes – charcoal with ink and what looks like gouache – on the pages of an accounts register kept by the East Rand Proprietary Mines Company in 1906. We can see a stretch of ground changing subtly or suddenly as if we were observing different states of a painting. The sequence is preoccupied chiefly with these local changes, wrought by money and extractive industry; only near the end does the curve of the earth appear, as a warning about environmental degradation. Accounts and Drawings is one of Kentridge’s many small-scale virtuoso achievements. So too is Second-Hand Reading (2013), a flipbook drawn on the pages of a Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, and projected in a small room next to The Refusal of Time. A hint of the landscapes in Accounts and Drawings can be found here, along with free-standing studies – a bird, a singleton tree, the artist himself and his long-suffering Sancho Panza: the stove-top coffee-maker. Works like these address us quietly and clearly, over the fun and hubbub of the bigger pieces.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.