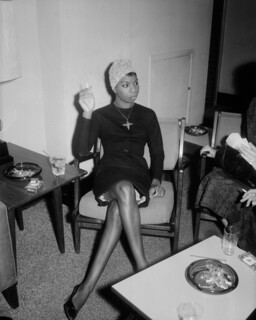

In June 1954, the tall, wary 21-year-old classical pianist Eunice Waymon found herself outside the Midtown Bar and Grill in Atlantic City, New Jersey a few blocks north of the Boardwalk. Waymon, who had spent most of her hard-striving life in North Carolina, the sixth of eight offspring born to grandchildren of slaves, had never before been in a bar. She had been hired at $90 a week to play five hours a night. The salary, considerably higher than her pay as an accompanist to a New York vocal coach, would help her to defray the cost of piano tuition and to pursue her lifelong ambition to become America’s first black classical pianist. By her own account, the Midtown was a ‘crummy joint’ but she approached it as a classical venue. For the gig, she brought her make-up, a pink chiffon dress, and a stage name, improvised on the spot, to hide her louche employment from her mother, a Methodist minister who moonlighted as a maid. ‘Nina Simone’ is how she announced herself to the Midtown regulars. With a glass of milk beside her on the piano, Simone shut her eyes and began to play. At 4 a.m., when the set was over, she approached Harry Stewart, the owner and ‘host’, to ask how he liked her playing. Why hadn’t she sung? he asked. ‘I’m only a pianist,’ she said. ‘Tomorrow night,’ Stewart said, ‘you’re either a singer, or you’re out of a job.’

‘I had a small voice, and the sense not to push it,’ she said later. As a child, she’d sung in church with her mother and sisters; she didn’t know, she said later, ‘that I could give it feeling with such limited means. My advantage was a perfect ear and that I knew how to play within my range.’ To fill each night’s long stint on the Midtown’s piano stool, she began to improvise with registers and inflections and to pronounce her own feelings inside the songs. To her surprise, she enjoyed the exercise. ‘The Midtown … made me looser,’ she said.

Singing was self-defining: it allowed Simone increasingly to speak from her black experience, not from the white milieu of classical music. ‘I didn’t know I could improvise like that,’ she said. ‘All the time I was practising. I’d practise Bach and Beethoven and Handel and Debussy and Prokofiev. Man, all the talent that I had inside me, that was created from me … I didn’t know anything about those songs until I first started playing in a nightclub.’ She went on: ‘I was repressed to the point where I hadn’t played any songs of my own for 14 years, and I didn’t even know I had them down there. I didn’t know until I first started playing at the Midtown Bar.’ Nonetheless, at first she conceived of her singing as part of her piano recital – ‘the third layer complementing the other two layers, my right and left hands’.

Simone’s husky contralto almost immediately found an audience. ‘The place was crowded. Couldn’t get in,’ her brother Carrol Waymon recalled of her initial wallop, in Alan Light’s gossipy What Happened, Miss Simone?, ‘inspired’ by Liz Garbus’s 2015 documentary of the same name. The gravity and grace of her performance – her moody interpolation of lyrics played against a filigree of dissonant chord clusters – was a new sound which won a new kind of attention at the Midtown. ‘No talk and no whispering, just music,’ her brother recalled. Over the next two years, her billing went from ‘continuous entertainment’ to ‘new sensation at the piano’ to ‘the incomparable Nina Simone’; yet she still felt ‘dirtied by going into the bars’.

The edgy emotional intelligence of Simone’s singing broadcast not just a new sound but a new time. Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne, Nat King Cole – great black song stylists who emerged out of the 1940s and crossed over into the commercial white mainstream – succeeded precisely because their tone and diction took race out of their voices; they swung but without soul, which made the songs and the singers ‘easy listening’. ‘Easy’ wasn’t a word that was ever associated with Simone. In her life and in her lyrics, she always found drama. The feelings she called out of herself were complex and unsettling. She could be playful, cruel, arrogant, rapacious, furious, joyous, bereft. Her singing was at once ravishing and lacerating; it left its mark. ‘She didn’t sing jazz, because in jazz you have to submit to the force of the band – it’s a collective experience and I don’t think Nina liked to play like that. I think she liked it to be about her,’ the African-American music and cultural critic Stanley Crouch said of Simone’s musicianship, adding: ‘Her sound is freer than many sounds because she doesn’t imitate an instrument. She actually wants her sound to be a human sound.’ Listen to the resigned loneliness in her magnificent, trademark version of Gershwin’s ‘I Loves You, Porgy,’ released on her first 1958 album Little Girl Blue and in 1959 as her first hit single, in which she drills into the lyric to uncover a new seam of intimacy and anguish. ‘I love you … Porgy!’ she sings, her breathy voice cutting out the demotic ‘s’ of the song’s title, then taking a beat before it rises on the name as if a plea. ‘Don’t let him take me/Don’t let him handle me/with his … hot hands.’ On the same 1958 record, she pumps up ‘My Baby Just Cares for Me’ with a frisky stride piano; again, her plangent rendition of the album’s title song begins with her suggestive improvising of ‘Good King Wenceslas’ and Bach figures as if the singer were distracting herself at the piano from the self-pity of the lament in which the song shows her to be stuck.

Sit there and count the raindrops

Falling on you

It’s time you knew

All you can ever count on

Are the raindrops

That fall on little girl blue.

As social unrest began to rumble through America in the early 1960s, Simone’s raised voice, her particular combination of truculence and artfulness, spoke to a voiceless, demoralised African-American community; it was a thrilling antidote to what Zora Neale Hurston called ‘the muteness of slavery’. ‘In representing all of the women who had been silenced, she was the embodiment of the revolutionary democracy we had not yet learned how to imagine,’ Angela Davis observed. ‘My people need inspiration,’ Simone said. In the spectacle she made of herself as well as in her voice – ‘I want people to know who I am,’ she said – Simone became a race champion. In the mid-1960s Vernon Jordan, the head of the Urban League, asked her how come she wasn’t ‘more active in civil rights’. ‘Motherfucker, I am civil rights,’ she replied. She was the first African-American performer to wear an Afro and to adopt African dress, ‘the first true music industry radical feminist’, according to Pete Townshend. In the process, Simone and her songs – the performance of self – had become part of the ground on which African Americans stood. ‘White people had Judy Garland. We had Nina,’ the comedian Richard Pryor said.

Simone’s voice answered the radical call for a profound articulation of the Black Tradition and incidentally made her ‘the patron saint of rebellion’, according to Crouch. Her singing, an African-American critic wrote in the Philadelphia Tribune in 1966, brought the listener ‘into abrasive contact with the black heart and to feel the power and beauty which for centuries have beat there’. Take her extraordinary ‘Be My Husband’, conjured mostly with clapped hands and stomped feet, which becomes a field chant, forcing ‘an awareness of what the blood knows and the mind has forgotten: a sense of origin’, as August Wilson said of the blues.

Be my husband man I be your wife

Be my husband man I be your wife

Be my husband man I be your wife

Loving all of you the rest of your life yeah

Simone’s voice – its power and penetration – was her achievement; she insisted fiercely on proper attention being paid to it. (In the Liz Garbus documentary you can see Simone in high dudgeon, pushing up from the piano and pointing to a hapless paying customer. ‘You! – Sit down!! Now!!!’) However, for most of her early life, as Light’s biography inadvertently shows, she was voiceless.

Simone grew up in a pious household, with a stern, distant mother who never hugged or kissed her; her beloved father, a jack-of-all-trades, was sidelined by illness during part of her childhood, which deprived him of a breadwinner’s authority. Emotional impoverishment was an even greater deprivation than lack of money. The sadness which would seep into her songs contained a solitude which was part of her confounding early inheritance: love that was not love, a parental presence that was not presence. ‘I needed to touch. I needed someone to play with me,’ she said. In the strict Waymon household, seriousness ruled, and Simone knuckled under. ‘There were never any jokes … never any games. My mom didn’t allow Chinese checkers, she didn’t allow cards. No dancing, no boogie-woogie playing. Everything was “no”.’ Fearing the withdrawal of her mother’s conditional affection, she was dutiful to a fault. ‘I never disobeyed at all. Never.’ She put her unexpressed and inexpressible feelings into the long hours of piano practice, and in her surrender to the keyboard, found a way to mother herself. The containment, playfulness, undivided attention and joy that were absent at home, she found at the piano.

In her family Simone was idealised as a ‘genius’ but not seen for herself. Playing the piano was how she won attention and affection from the world. (‘I need people to like me in order to like myself – I can’t seem to do alone – my ego and self-confidence was shattered somewhere,’ she wrote in an adult diary.) She grew up in a paradoxical emotional climate of grandiosity and insecurity. At two and a half, she’d memorised and played ‘God Be with You Till We Meet Again’, a spiritual that her mother used to play; according to Simone, her parents ‘literally fell to their knees’. ‘It’s a gift from God they cried.’ ‘Anything musical made me quiver ecstatically, as if my body was a violin and somebody was drawing a bow across it,’ she recalled. She was playing piano at her mother’s church services from the age of three and by the age of five was the regular pianist at the Tryon, North Carolina Methodist Church, her mother’s ministry. ‘The little prodigy’ was her nickname in town; at home, she was excused from domestic chores. ‘She was preserved,’ Simone’s sister Dorothy said. ‘Her fingers were protected.’

When her mother, Mary Kate, drew the talent of her daughter to the attention of Katherine Miller, a white woman for whom she cleaned house, Simone found her first patron. Miller paid for the piano lessons which the Waymon family couldn’t afford and steered the child at the age of five to Muriel Mazzanovich (‘Miss Mazzy’), the British piano teacher who became ‘her white Momma’. ‘She took more care of me than my mother,’ Simone said, who walked two miles every Saturday to ‘Miss Mazzy’s house for an hour’s lesson’. In due course, Miss Mazzy organised local concerts for Simone, which helped to raise money for the Eunice Waymon Fund that she and Miller set up to further Simone’s musical education. Miss Mazzy latterly engineered Simone’s attendance at a six-week summer session at the Juilliard School of Music in New York. Recalling her white benefactors years later, Simone said: ‘The two of them got together and did a job for me … And on me.’

From the age of ten, practising six or seven hours a day, Simone submerged herself in the music and manners of the white world. ‘Bach made me dedicate my life to music,’ she said. Her bedroom walls were decorated with portraits of Bach, Beethoven and Liszt. For her high school years, a place was found at Allen High School for Girls in Ashville, North Carolina, where the faculty was all white and where she boarded for three years on a full scholarship, rising at 4 a.m. every day to practise the piano until school began at 7 a.m. ‘I traversed two worlds, two cities, two states of mind each week,’ she said. ‘I was a baby and bombarded by a weight heavier than most children bear.’ She felt she didn’t ‘fit in anywhere’.

Compelled to be a model child, then a model student (high school valedictorian), Simone was also a model of the Southern species that Zora Neale Hurston, a Barnard-trained anthropologist, identified as the Pet Negro: ‘someone whom a particular white person or persons wants to have do all the things forbidden to other Negroes’. The price Simone paid for her white punctilio was a deep, if unspoken, self-loathing. Her stage surname was borrowed from Simone Signoret; in the first flush of recording success, riding down the West Side Highway with her guitarist Al Schackman in her new red Mercedes 200 SCE convertible with red top and matching red leather luggage, she enjoyed cutting a dash with a long scarf which she let trail dramatically behind her in the wind. ‘Grace Kelly,’ she said to Schackman. In her private memos, which are the most interesting – and best-written – part of Light’s haphazard book, she spelled out her ambivalence about being black. ‘I can’t be white and I’m the kind of coloured girl who looks like everything white people despise or have been taught to despise,’ she wrote.

All her musical ambition had been directed at winning a place at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, a destination which seemed so inevitable her family moved north to be with her. But, at the age of 17, Simone was rejected by Curtis (two days before she died, they awarded her an honorary doctorate). She put the rejection down to racism. ‘Nobody told me that no matter what I did in life the colour of my skin would always make a difference,’ she said. ‘I learned that bitter lesson from Curtis.’ True or not, the narcissistic wound never healed; her humiliation fed a desire for revenge. She was so badly shaken by the failure that she rejected the opportunity to go to Oberlin College on a full scholarship. ‘I thought it was beneath my talents. Had I gone I would have polished my technique for a year and then I could have gone to Juilliard.’

Instead, she moved her bruised dream to Harlem. In her telling, after breaking up with her hometown sweetheart and going north, ‘I lost my love and gained a career.’ But her losses were greater than that. Having befriended a high-class hooker, Faith Jackson, who introduced her to bisexuality, she was confused about her sexual as well as racial identity. The 21-year-old woman who paused before entering the Midtown Bar and Grill on that June evening in 1954 had no career, no prospects, no life, and nothing to fall back on other than a tarnished faith in her own gift. She was a stalled, lost soul.

Singing stops stuttering; Simone’s increasing success brought a new kind of flow to her life. ‘She has hit the Big Town, and the big towns, the LP discs and the TV shows – and she is still from down home. She did it mostly all by herself. Her name is Nina Simone,’ Langston Hughes kvelled in his newspaper column, ‘Week by Week’. ‘She is unique,’ he continued: ‘You either like her or you don’t. If you don’t, you won’t. If you do – wheee-ouuueu! You do!’ Hughes was the first, but not the last, black intellectual to mentor Simone, who now found herself in the company of the likes of James Baldwin and Lorraine Hansberry, who was particularly influential in raising her political conscience. Part of Simone’s momentum was down to her talent, and part to the burly macho former police detective, Andrew Stroud, who took over managing her blossoming career. He did a good job. ‘He used to tell me to put on the blackboard, I’ll be a rich black bitch by such and such date, and then I could quit. And I always believed him, and I never could quit.’

Stars are kings of capitalism, performing workhorses who prove that the system works. For Simone, the system seemed to be paying off. She shook the money tree. She had a house and garden in leafy Mount Vernon outside New York City, a gardener, a maid, a daughter, closets full of clothes, her own music publishing company, a music room of her own, a long list of high-class engagements, even two fan clubs. Stroud, a light-skinned black man, was the cleft in the rock of the world where the lonely fragile Simone could hide. (‘My Stud Bull! And sometime Bully,’ she called him.) Their relationship recapitulated the paradigm of Simone’s masochistic connection to her cruel mother. She both loved Stroud –‘You gave me my life back,’ she wrote to him – and feared the quality of his attention. ‘You worship me but that’s a far cry from love, motherfucker,’ she wrote to him. Stroud may have been guilty of putting Simone on a pedestal; he was certainly guilty of knocking her off it. On the night of their engagement, liquored up and jealous of a fan’s attention, he started hitting her in the taxi, and continued in the street and up to his apartment, where, his knuckles bloody, according to Simone, ‘he tied my legs and my hands to a bed and struck me, and raped me, and fell asleep.’ Reader, she married him.

In a short time she began to question whether the battle for popular success was worth the prize. Stroud, she said, ‘loved me like a serpent. He wrapped himself around me and he ate and breathed me, and without me he would die.’ Inevitably, undermined by the rage she had to contain, Simone began to act out. ‘I must hurt someone – I can’t help it – I am also pushed too far,’ she wrote to Stroud, trying to reason with her empire-building Svengali. She went on:

Work most of the time is like deadly poison seeping into my brain, undoing all the progress I’ve made, causing me not to see the sun in the daytime, not to smile, not to want to get dressed, not to care about anything except death – and death to my childish mind is simply escaping into the unconscious. Lisa [her daughter] is okay as long as she doesn’t want too much from me and is just content with my presence and letting me watch her at play.

On 15 September 1963, the Ku Klux Klan bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four children. On hearing the news, Simone rushed to her garage to make a zip gun. ‘I had it in mind to go out and kill someone,’ she said, ‘Someone I could identify as being in the way of my people.’ In the end, her murderous fury was projected into the first of her serious political songs. Her ambition was ‘to shake people up’: ‘I want them to be in pieces. I want to go in that den of those elegant people with their old ideas, smugness, and just drive them insane.’ ‘Mississippi Goddamn’ was written in an hour. Set to a sprightly backbeat – ‘This is a show tune/But the show hasn’t been written for it yet’ – it created a seismic disturbance. ‘You don’t have to live next to me,’ Simone sang. ‘Just give me my equality.’ Instead of hymning non-violence and stoic endurance, the song promised mayhem:

Oh, but this whole country’s full of lies

You’re all gonna die and die like flies

‘We all wanted to say it, but she said it,’ the comedian Dick Gregory recalled: ‘That’s the difference that set her aside from the rest of them.’

Caged in private and a freedom fighter in public, Simone found herself by degrees at the crossroads of her marriage and her career. Her obsession with social justice put her at odds with her husband’s obsession with success. She wanted to make a different kind of killing. The Movement gave a mission to her voice; its promise of action was an antidote to her ennui. ‘All I can do is expose the sickness, that’s my job,’ she said, adding: ‘I am not the doctor to cure it however, sugar.’ ‘Backlash Blues’, set to Langston Hughes’s last poem, stared directly at the Gorgon’s head of racism and defied it:

You give me second-class houses

And second-class schools

Do you think that alla coloured folks

Are just second-class fools

Mr Backlash, I’m gonna leave you

With the backlash blues

At the finale of her thrilling, head-bobbing rendition – you can watch it on YouTube* – Simone, full of grudge and glee, pushes up from the piano to face the audience and speak the poem’s warning, which in her mouth feels like a curse: ‘You’re the ones who’ll have the blues, not me!,’ she sings. Her voice, raw with rebuke, leaves its audience with a bruise which has never lost the throb of pain.

By the late 1960s, Simone’s message from the stage grew fiercer and more apocalyptic. In her version of Brecht/Weill’s ‘Pirate Jenny’ from The Threepenny Opera, she turned the swashbuckling saga into a call for racial retaliation. ‘Kill them now, or kill them later,’ she sang with unmistakeable emphasis. ‘I’m not non-violent!’ she told Martin Luther King, when they first met. In private and in public, she didn’t back down from her bow-wow position; her deracinated behaviour was in some way a barometer of the American madhouse. On 13 August 1967 in Detroit, two weeks after a five-day race riot left forty dead and the city in ruins, she sang ‘Just in Time’ to the crowd, adding: ‘Detroit, you did it … I love you, Detroit … you did it!’ She was still trying to start a riot the following year, exhorting the crowd at an outdoor concert in Harlem: ‘Are you ready black people … Are you ready to smash white things, to burn buildings? Are you ready to build black things?’

The only thing she managed to burn down was the foundation of her own life. As early as 1967, there was a foreshadowing of collapse. Before one concert, Stroud found her incoherent at her dressing table, putting make-up in her hair, unable to recognise him. ‘I had visions of laser beams and heaven, with skin – always skin – involved in there somewhere,’ she said later, about her psychotic breakdown. The assassination of Martin Luther King was another crazy-making blow. ‘It killed my inspiration for the civil rights movement, and the United States,’ she said, dubbing the republic ‘The United Snakes of America’. In 1970 she divorced Stroud; by 1974, she’d left America more or less for good, shuttling for the rest of her life mostly between Europe and Africa. ‘Andy was gone and the Movement had walked out on me too,’ she wrote, ‘leaving me like a seduced schoolgirl, lost.’ The Movement had served her as an antidepressant. It had contained her rage and without it the volatility that made her exciting and eloquent on stage made her hectic and impossible off it. Her roiling emotions were distressing to her as well as to those around her. She sought help and found little. ‘I sing from intelligence,’ she said, but she couldn’t live by it. Her behaviour ran to sensational, self-destructive extremes. Over the next 19 years of her life – she died in France of breast cancer in 2003 – she was hauled off to a hospital in a straitjacket; discovered naked in a hotel corridor, knife in hand; tried to burn down her house; fired a gun at a record producer who she claimed owed her royalties, and at two French boys who’d interrupted her when she was practising. (She missed the promoter, but hit one of the boys in the leg.) The tyrannical will that helped forge the artist ruined the life. She was physically and emotionally abusive to her daughter; she quarrelled with her family and fell out with her once-beloved father, refusing to see him even on his deathbed. As her emptiness grew, so did her grandiosity. ‘I compare myself to a queen,’ she told Time in 1999. ‘A black queen … I have to be a queen all the time.’

Her distressing expatriate life had its small victories even so. In 1977, she was awarded an honorary doctorate by Amherst College. (She insisted after that on being called ‘Doctor Nina Simone’.) Her 1958 recording of My Baby Just Cares for Me became the anthem for a 1987 Chanel ad campaign, subsequently going gold in France and platinum in England. In 1991, she sold out the Olympia in Paris for almost a week. Simone understood her singing as a form of enchantment. ‘You can hypnotise an entire audience and make them feel a certain way,’ she said. ‘It’s a spell that you cast.’ Her singing always worked its magic on the public but not on her life, which didn’t stop her from trying to cast its mojo over herself. At night, she said in 2001, ‘I sing a song called “Jesus Paid It All”. I chant it.’

Jesus paid it all.

To him I owe.

Sin has left the crimson stain.

He washed it white as snow.

She added: ‘I sing that over and over and over again. Until I fall asleep.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.