Constable , as the V&A’s press release puts it, is ‘Britain’s best-loved artist’, and that in a way is the problem. (Constable: The Making of a Master is at the V&A until 11 January.) While his contemporary Turner bestrides the history of European art, Constable remains a largely domestic taste. There was a time when almost every home had a reproduction of The Hay Wain. Tours of ‘Constable country’ on the Essex-Suffolk border were popular by 1893 and are still going strong. It all contributes to the image of a local artist painting agreeable scenes. Those who have looked more closely at his work have seen more in it, but disagree about what the more is. Roger Fry admired the energy of the sketches, the aspect of Constable that flatters posterity by seeming to point to Post-Impressionism and abstraction. Kenneth Clark also thought that the sketches had a ‘force of sensation’, but found the finished oils a ‘bore’. John Berger took the opposite view, that the completed works were rich in brilliant light effects, but the sketches were weakened by vague Romanticism. More recent left-wing critiques, especially since John Barrell’s The Dark Side of the Landscape appeared in 1980, have disagreed again, taking Constable to task as a reactionary Tory, sentimentalising and tidying up the rural poor.

Since 1888 when Isabel, Constable’s last surviving daughter, gave the Victoria and Albert the hundreds of drawings and sketches that were the contents of her father’s studio, as well as a bequest of three finished oils, the museum’s collection has been at the heart of Constable studies and the management of his slippery reputation. It has borne the challenge bravely. The late Graham Reynolds, keeper of the Department of Paintings, wrote the catalogue raisonné and Mark Evans, curator of this exhibition, was also responsible for John Constable: Oil Sketches from the Victoria and Albert Museum, which toured to the United States in 2012. But while that exhibition could be presented as offering an insight into the artist’s working methods, the present show, perhaps hoping to underpin Constable’s position in art history, strains for an argument. The one it makes, that Constable was not a naive artist painting directly from nature but was influenced by old masters and contemporary painting is true, but nobody has seriously questioned it. As Ernst Gombrich wrote in 1960, ‘That the artist can learn from tradition … it never entered Constable’s mind to doubt.’

His friend and biographer C.R. Leslie described the attic bedroom in Constable’s house in Bloomsbury as so densely hung with engravings that ‘his feet nearly touched a print of the beautiful moonlight by Rubens.’ The most effective display in the exhibition brings together as many of those images as possible to re-create the scene that greeted Constable each morning. Elsewhere the point becomes laboured, the material better suited to a learned article than an exhibition. The real joy of the show is the opportunity to see the range of Constable’s work throughout his life and to revolve once more his curious afterlife.

It is ironic if perhaps predictable that the sustained comparison with earlier artists serves to emphasise the extent to which Constable was of his own time: a Georgian, a Romantic, the product of a generation that saw revolution abroad and disorder at home, that was torn between reaction and radicalism and lived on the brink of modern science and industrialisation. There is nothing very surprising in his choice of mentors and models, notably Claude, on whose landscapes the Picturesque taste of his own day was largely based, and the Dutch and Flemish masters who were also popular with his contemporaries. More revealing is what he did with them. Rubens’s Landscape by Moonlight is shown here with Constable’s Moonlight Landscape with Hadleigh Church of 1796. The influence is clear while the titles reflect the difference, the contrast between Rubens’s general and Constable’s particular scene, between the breadth of the 17th century and the intimate specificity of the late 18th. In Constable’s picture firelight from a Gypsy encampment reddens the tree trunks in the wood to the right of the canvas. It is a miniature scene within a scene conceived with a knowledge of Wright of Derby’s popular night pieces, The Blacksmiths’ Shops and An Iron Forge.

The scenic possibilities of industrialisation, the blazing furnaces and hurtling engines that attracted Turner, didn’t interest Constable greatly, though the exhibition includes one oil sketch of a kiln on Hampstead Heath, its red glow and black smoke against yellowing autumn leaves and a sky of high clouds. As in his politics so in his art his response was to resist, to look back from a personal as much as a historical perspective. His most famous mature works were done largely from memory, after he had left Constable country and moved to London in 1817. The Hay Wain was painted in Keppel Street on a site that now lies beneath Charles Holden’s monumental London University Senate House and was, even then, entirely urban. The painting recalls the pre-enclosure landscape of Constable’s childhood. Its setting, at noon, evokes a high point, a brief moment of stasis in the business of life or of a lifetime. It is in such latent tensions between one moment and the next, movement and stillness that Constable’s peculiar genius is most striking.

Responding to contemporary opinion he noted that his work had been condemned by a French critic as being like ‘rich preludes in musick … which mean nothing’. Surely, Constable wrote to a friend, this was ‘the highest praise?’ ‘What is poetry?’ he continued, ‘what is Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner (the very best modern poem) but something like this?’ The Ancient Mariner has a narrative, but that isn’t its meaning, any more than Constable’s landscapes are documents of rural life and work. They are, as much as any poem, the products of emotion recollected in tranquillity, which isn’t to say that Constable was apolitical, any more than Coleridge was. A Tory, a landowner’s son who dreaded the Reform Act of 1832, his Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, painted in 1831 as the bill was struggling through Parliament, shows the cathedral, the beau idéal of English Gothic, under storm clouds riven with a great rainbow. By then Salisbury Cathedral had become a symbol for reformers like Cobbett as much as for Tories of all that was best and worst in England at a time when it was experiencing the most serious civil unrest in its history. Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows is not a polemic: it represents a moment of suspense at a point of crisis.

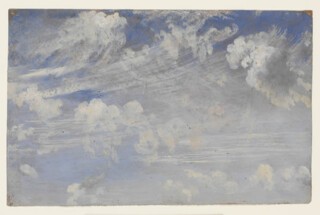

The current of contemporary ideas flows through Constable’s work. It is there in his remark that painting was a ‘science’, a loaded word at that date. William Whewell, prompted by Coleridge, coined the term ‘scientist’ in 1833, but before that there was, for most of Constable’s life, a free-flowing interchange between art and the ever expanding catch-all of ‘natural philosophy’. Luke Howard’s essay of 1803, ‘On the modification of clouds, and on the principles of their production, suspension and destruction’, established the categories, cumulus, cirrus and nimbus, by which clouds are still known. Howard’s taxonomy inspired Thomas Rickman to establish the phases of Gothic Architecture – Norman, Early English, Decorated and Perpendicular – on the same principle, and Howard’s clouds also lie behind Constable’s. His meticulous sky studies are often annotated in pencil. ‘Cirrus’, he writes on the back of one and ‘wind very brisk & effect bright & fresh. Clouds moving very fast with occasional very bright openings to the blue’ on another. If Keats affected to think that science had destroyed all the poetry of the rainbow, Constable saw how the close observation of the scientist well became a painter who was interested in rainbows.

The cloud studies are among those oil sketches of ineffable brilliance that Clark and many others have preferred since Constable’s death to the pictures he regarded as finished works, and they are well represented in the exhibition. As well as skies and landscapes there are scenes, like the fair in his native East Bergholt, where out of streaks of light and cloud and dots of white a landscape of tents and fair-goers arranges itself before the eye. The sketches appeal to us now in a way that Constable would not have foreseen or perhaps liked. That hardly matters. What the exhibition demonstrates is the range of an artist too often seen as narrow, and his mastery of Romantic spots of time. One of his strangest finished paintings, The Leaping Horse, is here; a canal-side scene in which a barge horse is being jumped over a cattle barrier on the towpath so that it can continue on the other side. Meanwhile the boat waits. Horse and rider are in motion against a scene of stillness. As a whole the narrative is undramatic to the point of banality, yet the picture is imbued with immanent mystery, with Constable’s idea of the poetic landscape which resonates and ‘means’ nothing.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.