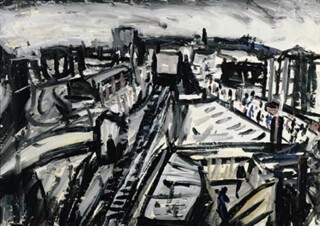

Silent, heavy doors open on a line of dense and minatory charcoal drawings, linked like coal trucks, and arranged on the floor in a provisional order – I visited before the all-encompassing Leon Kossoff show, London Landscapes, opened last month (it closes on 6 July). Tolerated afternoon light insinuated from a west-facing window, to be swallowed in that privileged and subtle incandescence they finesse in these off-Bond Street galleries. Pale grey chambers host a complicated negotiation between high art, patronage and publicity, with the challenge, for all of these, to confront this raw and overwhelming revelation of the metropolitan soul: one man’s repeated raids on, rebuffs and captures of certain favoured urban motifs. The hit is immediate. The confirmation that it really can be done: sixty years of making London drawings, often as preparation for paintings, but always because that is just how it is, a solid proof of continuity for man and city.

I was thrown off-balance by the intense energy of these marks: the dashes, counter-strokes, over-reaching arcs, sweeps and surges; the structural skeletons lodged in each of these panels. And by how, taken together, and processed down the length of the room, they amounted to something more: a history of struggle and release in the form of a monumental graphic novel from a remembered and reconstituted place. Tension and rapture. Excavation and elevation. The numinous Kossoff drawings are an autobiography forged through engagement with the dirty particulars of place. He’s like a man coming back from long exile in order to make a map of locations where he can begin to search for himself, to confirm his existence. There is a steady pressure to interrogate the specifics of a living past, the oases of ordinary activity that act like radio beacons: a postwar building site close to St Paul’s, a public pool seething with swimmers, a spectral staircase in the revamped Midland Hotel at St Pancras, the molten cliff of a school in Willesden like a glowing crown of red clay. The wrestling of mass into free articulation only confirms the sense of localised fragility. These things will disappear. And the witnesses with them. The pain in this contract is one of the sources of joy in the physical act of drawing: Blakean joy among soot and mud, chains and engines.

It has been said, in relation to his swirling child’s-eye visions of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s intimidating Christ Church in Spitalfields, that Kossoff assimilates hostility, confronting the alien stack of this Anglican invader in order to make stone spring upwards into the light. Kossoff speaks of the burden of accumulated memories. His earlier life in the streets surrounding the church created a ‘pressure’ that fuelled the urgency of his duty to work, to carry his drawing board, time and again, to places he acknowledged as sites of unappeased narrative. The act of making a drawing was recognition. When developers swept in, and architects laboured to visualise new towers, he celebrated the wounds. Kossoff favoured impressionist zones – stations, suburban streets, small public gardens – but his performance had the expressionist delirium of Ludwig Meidner. The drawings are land-scrapes: gouged, sculpted, pressed into an exhilarating calligraphy of affect. They do not belong within the English tradition of the pastoral, those tactfully organised views as records of continuity, promotions for aristocratic real estate. Kossoff’s figures do not own the ground, they are in motion, passing through.

Railways play a large part in the story. Railways as ladders of memory and as metalled rivers sliced by the branches of a cherry tree at the bottom of a Willesden Green garden. A chronological expedition down the length of the gallery begins with a funnelled spillage of tracks, converging on the western horizon, seen from a high bridge close to the studio Kossoff occupied in Willesden Junction. The railway drawings are epics of inhibited spontaneity, monochrome Turner seizures of elemental forces choked back by the broken ribs of cancelled strokes, weighed down under a curtain of solid smoke. Along the edges of the drawings you will find small puncture marks like sprocket holes on a strip of film. Many of these furiously worked sheets have been recovered from the studio, where they were pinned to the wall among postcards, names and quotations. This show, for all its generosity, represents only a fraction of Kossoff’s output, his daily practice. If a regular sitter was not coming to the studio that day, he took to the streets, journeying to one of his target locations: King’s Cross, Willesden Junction, Embankment, Kilburn. One of the chosen stations of a secular pilgrimage around railway cathedrals where humans flood like fleshed ghosts through spaces made strange by neurotic revision.

Kossoff walked around the show with me, pausing when I paused, shaking his head, perhaps things were not quite as bad as he had anticipated. The modesty was genuine, but difficult to comprehend in the face of such evidence of achievement. We talked about the way, when he came to paint the interior of Kilburn underground station, friends and family members appeared like welcome revenants. Sometimes there might be a voice: ‘Here comes the diesel.’ Kossoff’s grandson is not seen, but his presence informs the slices of trains caught in excited shorthand as they rush past the end of the garden. The intimate circle of the familiar is the support system for the painter’s raids on railway London. When we sat down, after our little tour, Kossoff quoted Blake’s Jerusalem: ‘The Male is a Furnace of beryll; the Female is a golden Loom.’ He is a great reader and a rememberer. ‘I behold them and their rushing fires overwhelm my Soul;/In London’s darkness, and my tears fall day and night.’

The coda to the show comes with the most convincing justification I have seen for those weeks of Olympic hallucination. When parts of London, away from the flares and trumpets of the action, enjoyed a quietness and a stillness that was quite unreal and outside time, Leon Kossoff returned to Arnold Circus in Shoreditch, to the Boundary Estate where he grew up. He no longer had the strength to take on a major painting, but he carried his drawing board, day after day, to make a series of flightier, pinker works. They move and shimmer as he moves, as he positions himself on the mound beside the bandstand to look back down Calvert Avenue to the site where his father owned a bakery. The Arnold Circus drawings, bereft of boast, are the perfect riposte to the unnecessary Cultural Olympiad. They generate emotion without that compulsion to improve, explain and make loud. Kossoff’s drawing board was left overnight at the artists’ studios that were once the school he attended. Freed from the obligation to act as outriders for future paintings, the Arnold Circus captures have a freshness and throwaway lyricism. Set alongside the impacted darkness of his View of Hackney with Dalston Lane, they float like feathers. The paintings from 1970-75, made in a studio that overlooked Hackney’s German Hospital and Ridley Road Market, come with such a burden of history, of matters extrinsic to the act of painting. Loss of physical strength, the stamina required to plant himself out there as a special witness, has relieved Kossoff of certain obligations. The Arnold Circus panorama, catching shifts in the constantly changing light, carries him back into the London dream he has made his own. Loved places have been absorbed into a skein of consciousness that, through the revelations of this dazzling show, become ours to share.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.