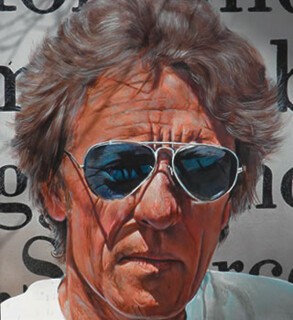

The publication in Britain of Edward Dorn’s Collected Poems is a big moment, a bonfire of the verities, for the embattled tribe of local enthusiasts, veterans of old poetry wars who are still, more or less, standing. Dorn’s face is news again, live and loud, on a cover laid out like a wanted poster, or the freeze-frame of a sun-bounced downhill skier, against a backcloth of enlarged script (his own words, not the usual blizzard of corporate logos). Here, cooling us out, is the essential leanness, the string and sinew of a Clint Eastwood with more candlepower and a much fiercer obligation to his nonconformist talent. Ed wrote his own one-liners. He wrote them, hand tied to the wheel like Count Dracula’s Whitby helmsman, as he commuted down 101 to a seasonal teaching job in San Diego. ‘A rather open scrawl,’ he said, ‘while one’s eyes are fixed to the road is the only trick to be mastered.’ He could hit it, when he chose, in a couple of lines. ‘The duty of every honest American/is to emigrate.’ ‘Recycling has grown to be/a major part of the pollution industry.’ The face on the Carcanet cover is a deeply scored calligraphy of experience, framed by rock-starish lightly silvered hair and reflective shades, behind which eyes that miss nothing flick from side to side, tracking through the exploitable sets of a working life: railside Illinois, Seattle and the Pacific Northwest, Alaska, Black Mountain College in North Carolina, a film festival in Havana, San Francisco, Rome, Avignon, Paris, London, Colchester.

That list comes in no particular order, but demonstrates a certain restlessness, and the gun-for-hire nature of academic near-employment twinned with necessary performance gigs and conference substitutions. Dorn trained himself to be a beautiful technical reader of the particulars of roads. He speaks of this, reporting on his expedition with the photographer Leroy McLucas through the Basin-Plateau, where Idaho meets Utah and Nevada. ‘I was tagging along making notes, looking. I was really looking at the kind of terrible awesomeness of the miscellanea of American upper landscape.’ That ability, ‘really looking’, was Dorn’s USP: an unblinking gaze behind the quasi-ironic aviator shades of a street-smart dealer in language. When J.H. Prynne dedicates his own single-volume gathering, Poems, to his friend and correspondent, he makes some play between the living spirit and the slick specs that were the signature of the poet’s transit through the noise of the white world: ‘For Edward Dorn, his brilliant luminous shade.’ The after-image flares and burns like the night the atom-bomb test in the Nevada desert overwhelmed the insolent rococo of the neon waterfalls of Las Vegas.

Dorn died of pancreatic cancer, on the cusp of the millennium, in December 1999. He took his alien, the tumour, with him. Which, as he reported in ‘The Decadron, Tagamit, Benadryl and Taxol Cocktail Party of 1 March 1999’, from Chemo Sábe, gave him considerable satisfaction. The tumour was interested in what interested him, but not interested in his essential fuel, love. The fruit of all those decades of hard research, two-lane blacktops and ravenous notebooks.

She’s like Wittgenstein’s lunch, utterly invariable,

and, she’s like your own private third world

she arrives and breeds like guinea pigs,

ever more progeny and evermore food

and the priest cells

demand evermore progeny and then

they all demand independence and this

is in Your territory. But then I see her

puzzled misapprehension and know

what she can never anticipate when my spirit

will watch this Bitch burn at my deliverance

in the furnace of my joyful cremation.

We were fortunate that Donald Davie, setting up an English Department at the University of Essex in 1965, invited Dorn to cross the Atlantic as a Fulbright lecturer. This was a pivotal episode for Dorn and for the mass of younger English poets who had heard rumours of Black Mountain College, read their Pound and William Carlos Williams, cannibalised Donald Allen’s influential anthology, The New American Poetry (1960), but never experienced a prime specimen of this fascinating otherness. Where Dorn was exceptional, as Prynne points out, in a conversation recorded at a reception after the funeral in Boulder, Colorado, was in the fineness of his ear ‘for spoken English and for the cadences of English speech, both grand and passionate, and ordinary off the street’. John Clare was an inspiration. Prynne took Dorn to Northampton to investigate the asylum where the poet spent his last years. John Barrell, another member of the new Essex University cluster, was working on his groundbreaking Clare study, The Idea of Landscape and the Sense of Place. When Dorn delivered The North Atlantic Turbine, his poems of English politics and place, to Stuart Montgomery of Fulcrum Press, the book was dedicated to Davie, Prynne and Tom Raworth (another Essex figure with whom Dorn had corresponded for years). A classic late modernist genealogy was being laid out; to be ignored, comprehensively, by the movers and promoters of the established verse manufacturing orders, those sharky cultural bureaucrats and strategic prize-givers who fix the syllabus and polyfilla inconvenient holes in sponsored periodicals.

The scene was being set for the arrival in Colchester of Charles Olson, last rector of the now collapsed and dispersed Black Mountain College, theorist and psychopomp of ‘Projective Verse’ and open-field poetics, author of the great post-Poundian epic The Maximus Poems, and headline star of Donald Allen’s anthology. At six foot eight or thereabouts, Olson was an inconvenient guest, as Tom Clark, another itinerant US poet and Essex academic, told me when I visited him in California. Sunset to sunrise, Olson would rumble, thump, burn, growl; whaling his chain of Camels, as Dorn said, in one gulp. He hibernated, postponing an expedition to Dorchester to dig into the records of the founding of the colony at Gloucester, Massachusetts, the germ of The Maximus Poems. ‘Oh yes,’ Dorn remembered, ‘those were amazing times. Jeremy Prynne came over from Cambridge. Olson turned our house into a kind of salon. Those were beautiful active times. I mean not literary active, but more expanded. It was never literary with Charles. He liked the literary, but that was a small role for him.’ A taxi arrived, sent by Olson’s wealthy lover, to carry him back to London. All his books and effects were piled on the roof, Dorn said, like a gypsy caravan or an Indian train.

It was Olson, with A Bibliography on America for Ed Dorn, published in 1964, who set the agenda for the younger poet’s lifelong engagement with the American West. This document, in part a letter, a set of instructions (in the exploded typography of Pound), a reading list, gave Dorn some of the tools he needed to assemble the volumes of close observation and laconic comedy now revealed through the multiple collisions of the Collected Poems. Olson was a theorist, a monster of endless high-risk nocturnal monologues. Dorn was a tough but delicately nuanced geographer, a discriminator of landscape. Clark makes those distinctions clear. ‘Ed was a lovely guy, with that brilliance of being on the edge,’ he told me. ‘He knew the world. And to travel with him, the landforms were a map he could read like a story. There is no comparison with Olson in terms of being able to understand these things. With Charles, it was all from books. Charles was Ed’s guiding teacher, the one who taught him that the adventure of the mind was something that he should embark on. Charles encouraged him. And he loved Charles for that, always.’

Although the appearance of Dorn’s Collected Poems, almost a thousand pages of them, is a substantial and welcome event, it is inevitably something of a tombstone. The book – for all its brightness of address, with the voices of supporting editors and friends – is an endgame, a public production. This comprehensive round-up, swallowing the original fugitive booklets along with unresolved sequences from the notebooks, is made uniform, laid across plains of white paper in orthodox ribbons of tarmac, tight to the margin. The hope is that new readers can be attracted onto the reservation. Dorn, who had been a hands-on printer, the man who went through the labour of setting and producing Olson’s Apollonius of Tyana at Black Mountain College, had his reservations when he was confronted with the unyielding lump of 652 pages of The Maximus Poems, posthumously assembled by the University of California in 1983. ‘The thing’s too heavy, should have been put on fine bible paper to give it wave,’ he wrote in Abhorrences: A Chronicle of the 1980s (1990).

And the inking isn’t perfect, it’s got California

stiff-as-a-board sensibility all over it.

The dark, threatening, diamond studded

baton of the neo cortex leeches out into the Nowhere.

It smells like eucalyptus instead of cod.But I’m concerned, everybody around here’s concerned.

Therefore we pass it around the table

and for some time thereafter

we throw words all over the page.

The facts are political. And it does matter. As Jennifer Dorn makes clear in her introduction to the Collected Poems, Ed published with persons, not publishing houses. There was always a firm engagement, a direct relationship carried through by regular and active correspondence, or face to face. LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka) argued out the first US publications, The Newly Fallen and Hands Up!; Tom Raworth, in England, another reliable card and letter-writer, delivered From Gloucester Out. In other words, poets published poets, signalling their affinities the best way, through production, while continuing to strengthen transatlantic traffic, through readings, academic exchanges, hospitality. Distribution was nicely random, with many of these books and pamphlets being trusted to the postal service, as gifts to peers, known and unknown. News had a frontier quality, coming in on the railway (in my case the clapped-out North London Line between Dalston Junction and Camden Road, for the great souk of Compendium Books). Control of production kept the process well away from corporate adventurism and required a network of fly-by-night independent bookshops. Dorn was comfortable in this world. Mike Hart, or one of the others from the communal Camden Town operation, would be on the phone to let customers know that the latest volume of Gunslinger had arrived. It really was as tight as that, 18th century in a way Dorn would have appreciated. That was his period. He took Johnson’s Lives of the English Poets as his prose model. ‘My desire,’ Dorn said, ‘is to be/a classical poet.’

Compendium Books, the window for Dorn’s uncollected poetry, was one of the miracles of the late 1960s and early 1970s, parachuted into the North London railway zone before the strangling apotheosis of Camden’s leather and vinyl street market. The success of this operation was remarkable. It grew, seemingly overnight, from a tall sallow man hunched in a wretched, holed-at-the-elbow, down-to-the-knees sweater at a foldout table with a dozen paperbacks laid on it, to an interconnected series of well-stocked caves, one of them given over entirely to poetry. I bought Dorn’s Gunslinger 1 & 2, published in England by the very handy Fulcrum Press, soon after the shop opened. The steady traffic towards Compendium, the meetings with knapsacked poets carrying their own wares, felt like a confirmation of that unitary vision expressed at the 1967 Congress for Dialectics of Liberation, up the road at the Roundhouse, the former engine-turning shed.

Stuart Montgomery, the publisher of Gunslinger (and of Robert Duncan, Gary Snyder, Basil Bunting, David Jones and Roy Fisher), a wispy-moustached medical man with a significant hobby, decided to do something about the sluggishness and indolence of mainstream critics. He flew off to Las Vegas and took a cab to the hotel where Howard Hughes was rumoured to be sequestered in the penthouse, intending to present him with a copy of the poem in which Dorn shaped his non-existence into a divine comedy of cocaine and cactus; virtual travel through high sierras and white deserts zeroing towards the vanishing line of the horizon like the bad craziness of a Monte Hellman western. It was that craziness we used to call the possible: that an invisible London publisher could provoke a reaction from the richest hermit on the planet, an unbarbered Texan tool-bit weirdo guarded by Mormon goons; that Howard Hughes, a fabulous entity capable of impersonation by Leonardo DiCaprio, would sue an impoverished poet and doctor with prime unsold stock stashed in his garage. Oh yes, those were the days. The bibliographic cornucopia of Camden Town, with its US imports, French theorists, New Age primers, was an admirable small business model. Money laundering to a purpose. The whole, pre-Thatcherite, wild dog enterprise was underwritten by the area’s other growth industry: recreational drugs. Arrest, incarceration, downsizing followed, with the shop taken over by a management committee of workers.

The discrete volumes that make up the Collected Poems came in all shapes and sizes, but the feel and texture was always striking. Dorn’s contribution didn’t end with the submission of a typescript. The early books from Totem Press were tough, stapled, easy to handle. Fulcrum offered cloth-covered boards, dustwrappers and screened Dorn portraits by Ron Kitaj. Recollections of Gran Apachería swaggered out of San Francisco like a comic on cheap pre-smoked paper. They were received, devoured, commented on, with a special kind of intensity. Now the exhaustive, and frankly exhausting, cartography of the trawl through the Dorn oeuvre presents us with something as heavy as a cabin trunk of severed limbs packed at an improbable density for deposit in a left-luggage office. That image is sustained by the belief that a certain kind of book, produced by poets, and frequently published by them, and delivered to a modest audience of fellow practitioners, could exist and thrive only in a culture of small independent shops, with complex agendas, operating at the outer limits of the possible. The arrival, if it is achieved, of a sepulchral Collected Poems, makes an appeal for canonical status. Dorn’s big book has a terminus quality not found in the collection of Prynne’s work put out by Bloodaxe. The Prynne Poems have been revised, corrected, added to, and somehow, through layout or spacing, the right amount of white breathing space, they offer a reasonable simulation of their original appearance in limited editions, very much designed and controlled in distribution by the poet himself. That fierce independence is an absolute and maintained condition of publication.

But the compacted meteorite of the Dorn Collected Poems, so rich and dense, now bombed into our cultural badlands, offers spectacular rewards, as the strategic shifts and heretical inspirations of the poet’s long career are revealed. First, his courage. Then his persistence. Out of the mid-continental hardship of his beginnings in Illinois, through years of physical labour and migration, Dorn refined his ability to articulate a precise report from wherever he stood. He mastered a ‘terrific actualism’. Clark explained how, looking at the land with an eye trained by Olson and by the geographer Carl Ortwin Sauer, Dorn learned to see its crucial role in determining cultural and individual fates: ‘A prairie village called Chicago,’ Olson said, ‘is still, despite itself, a prairie village.’ Dorn would launch one of his seminars by unrolling a railroad map of the US, which showed the sections awarded to the piratical magnates of the 19th century by giveaways of public land. He identified, most powerfully, with the Apache, the warrior remnants of the southwest.

The first law of the desert

to which animal life of every kind

pays allegiance

is Endurance & Abstinence

Dorn’s breakthrough arrived with the American epic Gunslinger, initiated by poems begun in Colchester and published, as tail gunners, in The North Atlantic Turbine. His always acute sense of history was heightened by the casual way that a morning stroll through the old garrison town brought him up against the bulwark of the Roman wall. His true territory, the American West, was now seen during a visit, under the moon’s ‘rough coin’, to the local Odeon for The Magnificent Seven, a Kurosawa film given the Hollywood treatment, in which a Mexican samurai is played by a hyperactive German. Just the kind of arbitrary, credit-juggling cultural flimflam that fired the super-hip comedy of Gunslinger. The grand mythopoeic structures of Pound and Olson, magnificent but unresolved, beacons of high modernism, were succeeded by Dorn’s synapse-frying Lenny Bruce performance, long sections of which he read, at various English venues, to hypnotic effect. With his belief that all poetry was derived from either the Iliad or the Odyssey, siege or quest, Dorn sculpted Gunslinger from the cast of John Ford’s Stagecoach sent out on the road to nowhere (or Las Vegas) in a chemically induced haze. Some commentators have read the progression by way of the marginalia of available and site-specific drugs: grass, LSD, cocaine.

Questioner, you got some strange

obsessions, you want to know

what something means after you’ve

seen it, after you’ve been there

or were you out during

That time?More likely you can’t keep your nose

out of those $50 bags,

observed the Horse. Anyway

we can drop it off at a bus stop

as we go thru Albuquerque

the populationll never know the difference.

The timelessness of New Mexico’s bandit opportunism means that Dorn’s characters fit very comfortably into the world of the TV series Breaking Bad (celebrated in the LRB of 3 January by James Meek). Dorn, forty years ahead of the game, exploited that clarity of light, where bad things have a hyper-real outline and the borders between countries and states of consciousness are dangerously porous. As a former high school quarter-miler, he was alert to the ugly potentialities of college athletes being industrially grazed on steroids, and of dysfunctional troglodytes with mail-order weaponry. He treated the supermall parking lot, and the snarling dogs in pick-up trucks, with the glancing precision Wordsworth reserved for changing seasons and solitary reapers. One of the charms of Gunslinger, perhaps anticipating Breaking Bad, was the Literate Projector, an instrument intended to uncover a new form of literature ‘which was Already There’, while restoring big novels to a form suitable for future internet consumption.

To put it in another Can

the Literate Projector

enables the user to fail insignificantly

and at the same time show up

behind a vocabulary of How It Is

The visceral excitement palpable in the performance of the writing of Gunslinger, supremely a work of its moment, faded. Dorn recognised early the bleakness of the 1980s, when a Gunslinger president operating with less battery power than his talking horse would front for the bankers and corporate despoilers. He chose not to publish for much of this period, but to assemble instead, from an amused and alarmed scrutiny of newsprint, the sequence that became Abhorrences. The poems could be called compulsively occasional, whips and scorpions of electively intemperate satire. ‘My tongue has been/my genius and my downfall,’ Dorn said. The position was not popular and he took pride in that. Some of the poems were as taut and crudely signalled as bumper stickers. ‘Mediocrity rises to the top in America like cream on milk, and it always has,’ he remarked. ‘If you’re a writer who lets these things bother you, you’re in the wrong business.’

The coming gossip-stew of the internet didn’t help. ‘Email is MEmail,’ Dorn reckoned. Private remarks or classroom provocations went virally rancid as he was whistled and gibed at for his scorn towards all manifestations of political correctness. Multiculturalism in most of its discursive forms, Dorn said, was ‘the cult par excellence of late imperialism’, dogma customised to serve the agendas of strategic internationalism. Such a position, as Clark noted, laid Dorn wide open to the self-inflating hysteria and reflex moral outrage that were the defining characteristics of Pacific Rim academia. ‘In Boulder, if you tell an obscene politically incorrect joke, someone may laugh,’ Clark said. ‘And if you say something incredibly insulting to a person of another race, and you are incriminating yourself in every deep form of awfulness, they laugh. Ed found that he couldn’t get a reaction. So he increasingly exaggerated the attempt, by saying more and more outrageous things. His students, who were all poetry students, will do anything they think will help locate themselves and give themselves some minimal celebrity. Several of them spew back reports of things he said. And distorted, illiterate, stupid versions. And that began the process that led to the noose being put around his neck.’

Out of favour, and under attack from twitching fingers, Dorn gave his attention to European heretics, the Cathars of Languedoc. He wanted to go to Rome, where he visited the room in which Keats died, and noticed the abundance of feral cats on the streets. The wheel had turned full circle. He was being published, once again, by small presses in England. The poet Nicholas Johnson, through his Etruscan Books imprint, delivered Westward Haut and High West Rendezvous. ‘It’s a lot easier to be a heretic than it used to be,’ Dorn remarked. ‘There are more religions willing to kill you.’

My rendezvous with Dorn occurred in Bath in 1999. He was stepping westward to witness the solar eclipse, which he described as a ‘big event’. Jeremy Prynne was with him. They had read together at the Arnolfini gallery in Bristol. The unusual, probably unique, aspect of this was that Prynne never gave public readings of his poetry in England. He explained once that there might be a confusion of identity; he had a professional role as lecturer and tutor. The other business was conducted on his own terms. He might perform in Canada or Paris, but not here. So this was something very special. And given, without prior publicity, out of respect and friendship. Prynne spoke of his admiration for ‘Thesis’, the opening poem of The North Atlantic Turbine, a poem of the far north written in Colchester. Dorn arrived, Prynne recalled, at a remote settlement in the Northwest Territories, so impoverished that the people there had no desire to know anything of casual visitors. They turned their backs on them, pushing Dorn, not towards resentment or shame, but pride: the rare achievement of getting the complicated scene down in measured, careful description. Mapping it just as it stood. ‘They have gone who walk stiltedly/on the legs of life.’ This is a great poem and a great report. It lifts like frozen smoke from the page. ‘The fallen are the pure Children of the Sun.’ I was involved with filming the Dorn part of the evening, none too effectively, and keeping my distance. Prynne of course banished the cameras and ripped out the microphone. He explained, quite slowly, what he was going to read. And then he read it, without Dorn’s anecdotal asides and obvious, chemically enhanced emotion. He read the whole book.

When we met next day, by arrangement, in the garden of a cheese-stone Georgian house in Bath, it wasn’t easy to set aside the knowledge that this would be one of the last interviews. Dorn had always been lean, hard times known and survived. But there was no surviving the evil pregnancy of the tumour, or the news from Baghdad, that ruined ‘Cradle of Civilisation’. ‘My tumour is interested in what interests me

What were Dorn’s memories, I wondered, of his years in England, in Colchester and London? ‘A lot more traffic and a lot less clutter. The traffic, as random as it sometimes seemed, seemed also purposeful. People actually did have things on their minds, no matter how strange those things were. They were actually going to a place, no matter if they arrived there or not, or if it was the wrong place. For a poet the world is always static in the sense that you’re a mass observer and you can’t afford to care whether people are busy or not. You’re a witness.’

And the Arnolfini reading, did it matter that there was no proper documentary record? ‘I think last night’s reading was historically interesting and significant. But things of that nature have to be borne away by the witnesses. Sometimes I think that it’s a shame it’s not captured. But, in a way, it’s such a moment that capturing it is defeating it.’

I thought about a story that is not part of the Collected Poems, but which demonstrates, right back at the start, why Dorn has been such an abiding influence for me. He had taken on the task of driving through the Basin-Plateau, but he had trouble deciding just what the job was. The people there didn’t need him. He didn’t even know what to call them. They were not Indians or Native Americans or even Shoshoni. He wanted to bear witness, that was an obligation, even of youthful foolishness, drunken cow rides at midnight, everything. The trail led to a great-grandfather, 102 years old, living in complete squalor with a wife who was willing a death that was slow to come. To talk, Dorn had to put his mouth right to the old man’s ear. He could hear, but he wasn’t responding. Then he broke into a lovely, long line chant. It became important, Dorn says, to register this, beyond the immediate circumstances of the contrived meeting. ‘We think death is some rather large event. We don’t have the sense that death is simply another occurrence, like any occurrence that might happen on this string we call our lives

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.