There has been a certain amount of huffing and puffing among the usually imperturbable gallery-going set about David Shrigley’s Brain Activity exhibition at the Hayward (until 13 May). People who value the power of art to shock far too highly ever to be shocked by it themselves, have nevertheless been somewhat put out, complaining that Shrigley, who is best known as a cartoonist, should have been given a solo show in such a prominent venue for serious modern art. Shrigley himself, who describes his work as ‘somewhere between handwriting and drawing’, and furthermore ‘not the kind of drawing where you’re trying to get their eyes in the right place’, has confirmed that he is being taken ‘far more seriously’ than he should be. It is the irony of course that annoys his critics as much as anything.

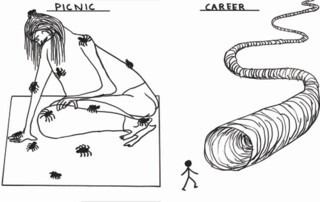

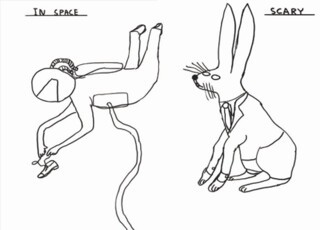

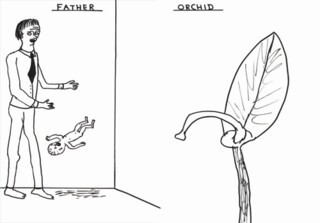

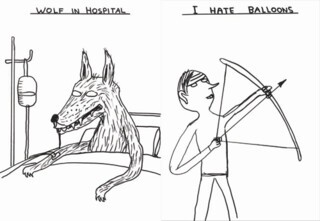

At the simple level of taxonomy the exhibition shows him to be more than a cartoonist. It includes painting, sculpture, photography and installation as well as the drawings which have made him popular. These are grouped into blocks where, instead of reading in sequence like a conventional strip, they ricochet off one another in a variety of moods. There are pure, Saul Steinberg-like jokes such as the man invisible behind his newspaper with its two headlines, ‘Misery’ on the front page and ‘Sport’ on the back. There is the blotted aphorism of ‘when you’re playing against yourself it’s always your move’ over a hand about to lift a misshapen chess piece. And there is Shrigley’s all-pervading anti-cuteness in ‘family camping holiday’, which shows three smiley faces labelled ‘me’, ‘mum’ and ‘dad’ each peeping out from a different tepee under the explanatory ‘we have to have separate tents because we all stink.’

Not quite satire, not quite comedy, the mood of the drawings swerves between irony, melancholy and a certain ruefulness. To some extent, like all cartoons, you like them or you don’t, they either hit or miss your take on daily existence. But the effect en masse is cumulative. They pass the test an exhibition sets: more is more. Shrigley worked for a while as a political cartoonist for the New Statesman, but gave it up as too restrictive. The targets of his drawings are not individuals so much as the general human and animal condition. This is less true of the other work in the show, in which the self-deprecating humour extends to the teasing deprecation of some of his fellow artists and indeed the viewer.

One of the ways in which Shrigley offends against the tenets of much contemporary art practice is that he admits to presenting a persona in his work. He does not offer the direct expression of interior experience or conviction the Romantic tradition requires. With the sculpture in Brain Activity he moves on from persona into something more like impersonation. There is his Martin Creed, an animation of a hand turning a light switch on and off; his Gillian Wearing, a stuffed dog holding a placard saying ‘I’M DEAD’; and his Andy Goldsworthy, a photograph of some nicely coloured leaves, on one of which is written ‘one day a big wind will come and’. The cartoonist exaggerates for effect. Here, Shrigley suggests, are some rather simple effects for which exaggerated claims have been made. The best-aimed shot is the puppy with its simultaneous poke at cuddly anthropomorphism and, perhaps, the cheapness of the emotion evoked in Wearing’s photographs, famously the one of a clean-cut, well-dressed man holding a handwritten notice saying: ‘I’M DESPERATE.’

There is an element of audience participation too. Most people miss Rat the first time round and have to go back for it. And the doorway shape cut out of one of the interior partitions at floor level encourages you to get down on all fours to look through it. The only point of this, as far as I could tell, is to make you feel foolish and conspicuous. At the end if you want to pay £6 to go home with a Shrigley bag that says ‘museums are full of crap’ on the side, you can.

Sometimes the impersonations get too easy and verge on the glib, as in Five Years of Toenail Clippings, solemnly presented in a glass sphere. They work better when he takes on bigger subjects. The wittiest piece is Finger, an immensely elongated bronze finger stretched, in the manner of Giacometti, into a cartoon Giacometti making an insulting gesture of itself. Less successful, but interesting, is Gravestone, an excursion into Ian Hamilton Finlay territory in the form of a granite headstone inscribed with a banal shopping list, ‘bread, milk, cornflakes’ etc, in carefully cut and gilded letters. As a comment on the uneventful lives commemorated by standard issue slabs in municipal cemeteries it is of a piece with the mood of Shrigley’s glummer drawings. As a critique it highlights Finlay’s qualities as a man with no persona but possessed of a violent sincerity, an artist whose irony, like his lettering, was sharper than Shrigley’s. Gravestone recalls Finlay’s more elegant Poussinesque stone marker Bring Back the Birch, which stands in Little Sparta – Finlay’s garden – in front of a small birch tree.

Finlay was also scrupulous about crediting his collaborators while the craftsman who made Gravestone remains anonymous. Shrigley, who claims to like the ‘crafty’ aspects of art, does do his own ceramics, however. They are as technically unrefined as the drawings, making play with modish studio pottery as well as the humbler end of domestic ware. The Philosopher is a planter in the shape of a lumpen bearded head with cacti growing out of it. It is just good enough to make the point and that is Shrigley’s greatest skill. In words and image he is a master of the exactly good enough. The eyes in his drawings are in just the right place for his purposes. As he said in a rare defence of his work, ‘the opposite of humour is not seriousness. The opposite of seriousness is incompetence.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.