I heard a few bars of Chris Corner’s song ‘I Salute You Christopher’ a day or so before the new IAMX album, Volatile Times, was released. The song, which appears on the album, is subtitled ‘Ode to Christopher Hitchens’:

I salute you Christopher

I salute your life

How you played the dice …

That ‘played’, in the past tense, has the ring of a funeral bell and a cracked one at that. I’d like to think that Sexton Corner had got this wrong, but what do I know? ‘I’m dying,’ Christopher Hitchens told Jeffrey Goldberg last year. ‘Everybody is, but the process has suddenly accelerated on me.’ The worry at this stage is that the system may soon have failed entirely and we’ll be left in the lurch. I don’t relish a world without Hitchens: along with many people, I like to hear from a man of principle at moments when recourse to principle strikes him as the greater part of valour, and listen in on his boisterous indiscretion when it doesn’t.

So no thanks, not ‘played’. Not quite yet. And who but the press looks forward to the homage from the Hitchens camp: the opera buffa novelists, the prickly atheists and Muslim-baiters, the warrior intellectuals pondering their just wars? Can anything strike a harsher blow to a celebrity’s standing, dead or alive, than the thoughts of his close friends? Hitchens has an army of those. The silence of erstwhile comrades and the barbs of enemies old and new will do him more credit.

Hitchens’s strong, almost gamey opinions produce a whiff of well-hung grouse in the reactions he provokes, and it tends to linger in the house. Stefan Collini, for the opposition, imagines Hitchens ‘as twilight gathers and the fields fall silent, lying face down in his own bullshit’ (LRB, 23 January 2003). Colin MacCabe, for the friends, tells us that passages of the memoir, Hitch-22, are ‘among the most affecting writing that I know in English’ (New Statesman, 17 November 2010). That’s a pungent claim and it bears repeating, or MacCabe must have thought so. Last month in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, he recalled telling Hitchens that the first two chapters of the memoir were ‘among the most affecting prose that I had ever read in English’. Hitchens, it seems, seldom meets with moderation and when he does, it’s apt to give way to exasperation. And so John Barrell, reviewing his book on Tom Paine (LRB, 30 November 2006):

Rights of Man (not The Rights of Man, as Hitchens persistently calls it) was written as an answer to Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France, and Hitchens tells us that among others who wrote replies to Burke … was William Godwin, which he wasn’t. He says that, unlike Paine, Wollstonecraft advocated votes for women, which she didn’t. Paine himself, Hitchens says, was not discouraged from writing Part One of Rights of Man by the rough treatment he received at the hands of a Parisian crowd following Louis XVI’s flight to Varennes. Nor should he have been, for Part One was published several months before the king fled and Paine was manhandled. According to Hitchens, Part Two was produced partly to explain to Dr Johnson the need for a written constitution, and partly to endorse Ricardo’s views on commerce and free trade, but when it was written Johnson had been dead for seven years and Ricardo, not yet 20, had published no views that required endorsing.

Hitchens’s fans are prepared to overlook the odd slip in favour of the flow (or the ‘words’, as Chris Corner goes on to say in his lugubrious ode):

Your words will live in us

Timelessly insane

Explosive, fresh and wise

But which words? ‘Wise’ he’s never done. And ‘fresh’? His flirtatious, boom-boody-boom examination of Tony Blair at close quarters is the best contender. Dr Hitchens says of the appealing patient who followed him into the deserts of Mesopotamia: ‘There is a moral pulse to be detected here and it’s quite a strong one’ (Vanity Fair, February). Hitchens in ‘explosive’ mode is hard to monitor: he is a one-man North Korea. For timeless insanity – and ‘timeless’, I guess, means anything either side of the long happy hour – one goes to the vexed sentence in the book on Paine that amused Barrell after a morning’s irritation: ‘Just as Paine’s joke about dress and lost innocence was intended to remind his audience of a mythical Eden, so his appeal to a lost but golden and innocent past was a trope that Milton and Blake knew very well.’

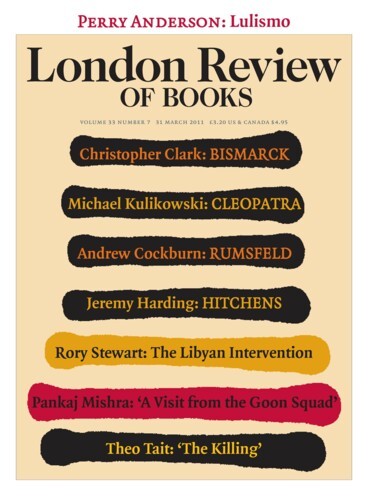

The LRB was one of several papers lucky enough to catch Hitchens before he took to writing so affectingly in English. There are many better sentences in the paper’s archive than these. There is also a consistency, in his pieces in the LRB (62 in all) and elsewhere, about his voice and his approach. One formula which he liked to set before the LRB: louche for three column inches, bare-chested at the barricades for another four or five, incisive over a spot of lunch, then back to the struggle. That Left Opposition-Balliol dialectic, a tussle between the truth-teller out on a limb and the inveterate cynic, made for gripping journalism and seemed to those who read him – as well as the editors to whom he condescended – to work pretty well. After 2001, as he became embedded, the contradictions began to multiply and then in the heat of battle to resolve. He was quite suddenly a sabre-rattling polemicist with stark views, and as the tensions in the writing slackened, to accommodate the weight of brute opinion, so the reader’s jaw fell open. The best remedy for the hanging jaw is generally to walk away with one’s hand cupping one’s chin, but you could also cure the condition by hearing Hitchens hold forth in person: to this day he is a captivating talker, as his recent recordings with CBS’s 60 Minutes attest.

Yes, but the writing. One effect of Hitchens’s movement from not quite left to not quite right is that he seems at one time or another to have covered every base. And so as you vainly attempt to flag down the later Hitchens, rumbling towards you in his juggernaut, you notice a charming younger man slipping from the trailer and escaping on a moped by a dusty track he’d charted earlier. The point you wanted to argue is one he’s already dealt with somewhere back down the road (and he’ll tell you exactly where). Much to your astonishment, he agrees with you entirely, he’s as true to you now, after his fashion, as he was when he first raised that very question. The Balliol boy wobbles off through the woods, while the juggernaut comes thundering on with a red-eyed ghoul at the wheel. And wait, there’s Martin Amis in the cab beside him, with a frozen alcopop in one hand and an unread novel by Victor Serge in the other.

Which is another problem: few of Hitchens’s friends are as clever, or fastidious, or well read, or hungry for the telling detail, as he is. Few have the same root and branch obsession with the recent past or the avenger’s recall (‘the necessity for long memory and sarcasm in argument’, as he wrote apropos the old left intelligentsia in New York). No one nowadays has his divorce attorney’s style when it comes to a historic grudge. It’s a particular, keenly attentive disposition and it needs people who can keep the conversation going. Thirty years ago, when I called Hitchens to set up an interview from a gloomy radio studio in New York, his answering machine announced that anyone with news of fame or money was welcome to leave their number after the tone. Irony and panache of that kind were rare among the left-wing producers with whom I worked at WBAI and brought a little air into the room. But I wonder now about the road to fame and money and how much more bracing it would have been to follow him along it if he hadn’t been obliged to break with his friends on the left, particularly the NLR crowd, who have their own juggernauts parked out the back. Hitchens has described Blair as a prophet unacknowledged in his own country and you could go along with Collini in seeing Hitchens himself as a flawed seer lying face down in his own bullshit or someone else’s – Chris Corner’s would do. But he seems to me a tempestuous figure with many devotees and enemies, and a shortage of equals. And when he falls it won’t be on his face.

That remark about long memory and sarcasm in argument was made in an essay he published 20 years ago in the LRB. It goes round the houses in an enchanting way – reading Hitchens always was an education – beginning with a swipe at the New York Times, plunging into the arcana of left tradition on the Upper West Side, ruminating on the source of Bellow’s pessimism and the fortunes of Augie March, flipping elegantly off to Norway 1936 (‘Trotsky is on the run’) and back to New York to assert that ‘all the strands of the “New York intellectual” milieu are in some sense Trotskyist or post-Trotskyist’ (4 April 1991). And so to the New York magazines, and a discussion of Jewishness (Hitchens was by this stage partly ‘Jewish’); from there to abstract expressionism and on to the schisms among the left ‘elites’. Now comes an update on the left’s failure to say anything coherent about the first Gulf War. ‘Only the Nation (for which, I should say, I myself write a column) opposed the escalation and published regular reminders that America’s role in the region is not that of a disinterested superpower. As I write, only the Nation has protested at the scale of Iraqi civilian and “collateral” casualties.’ We go out on a tribute to Trotsky: ‘In the rush of confession, revision, repudiation, self-advancement and mere ageing that has overtaken the New York crowd, the idea of the fearless unpublished, unimpressed and uncompromised intelligence has taken rather a beating. That is why, long after Trotskyism has become irrelevant, the admonishing figure of Trotsky himself has not.’

The following year – the year of lawyering dangerously, at least at the LRB – saw Hitchens’s wet job on Henry Kissinger (22 October 1992). As he does with many of his subjects, he walked straight up to this one and dropped the guillotine, likening the book under review – an authorised biography – to ‘the profile of a serial murderer’. Out came the rest in eloquent sequence: the stuff about Kissinger’s ‘cushy’ war; his ‘pathetic adoration of the winning or the stronger side’; his cool application of ‘wet smackeroos to the buttocks of the powerful’; his pitch for a ‘racialist and absolutist’ version of Zionism; his duplicity over Vietnam; and so to the main chargesheet – Bangladesh, Chile, Cyprus, Kurdistan, East Timor. And on in a moment to the argument with a certain kind of realpolitik, which is essentially the argument that brings us up to the minute, and the figure in the truck and trailer:

There have, of course, been brutal and cynical statesmen in the past. But they were generally statesmen – Talleyrand and Bismarck come to mind – who could show something for the exercise of realpolitik. Will anyone say what Kissinger’s achievement was? Will anyone point to a country, not excluding his own, which is in the slightest degree ameliorated by his attention? And the old ‘realists’, of Vienna and Locarno and Yalta, though they may have looked at nations and peoples and borders as disposable and dispensable, did not axiomatically confuse crudeness and brutality with strength and (a significant Kissinger favourite) ‘will’. They did not reach hungrily for the homicidal, self-destructive solution.

Much of this could be turned against the post-socialist Hitchens – the one who told Lynn Barber in 2002 that henceforth his politics would have to be ‘à la carte’ – or at any rate trouble the surface of his writing with bizarre reflections. But the enduring puzzle is the big one: a working intellectual framework – for instance socialism – isn’t something you abandon for reasons of principle, yet there’s more than a germ of principle, or the wish for principle, in a quarrel with crude realpolitik that ends up as a sterling defence of imperial adventure. Perhaps the writing is the overriding thing. That and the cause, any cause that ends with the gloves off. No doubt we should all have one. And a large following, though Hitchens might want to exclude Chris Corner on grounds that he’s already stuck him in the past tense and canonised him in the process (‘Saint Christopher of the truth’). That’s surely the worst of both worlds, even if you don’t believe there’s more than one.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.