Tariq Ali

A few weeks before the assault on Gaza, the Strategic Studies Institute of the US Army published a levelheaded document on ‘Hamas and Israel’, which argued that ‘Israel’s stance towards the democratically-elected Palestinian government headed by Hamas in 2006, and towards Palestinian national coherence – legal, territorial, political and economic – has been a major obstacle to substantive peacemaking.’ Whatever their reservations about the organisation, the authors of the paper detected signs that Hamas was considering a shift of position even before the blockade:

It is frequently stated that Israel or the United States cannot ‘meet’ with Hamas (although meeting is not illegal; materially aiding terrorism is, if proven) because the latter will not ‘recognise Israel’. In contrast, the PLO has ‘recognised’ Israel’s right to exist and agreed in principle to bargain for significantly less land than the entire West Bank and Gaza Strip, and it is not clear that Israel has ever agreed to accept a Palestinian state. The recognition of Israel did not bring an end to violence, as wings of various factions of the PLO did fight Israelis, especially at the height of the Second (al-Aqsa) Intifada. Recognition of Israel by Hamas, in the way that it is described in the Western media, cannot serve as a formula for peace. Hamas moderates have, however, signaled that it implicitly recognises Israel, and that even a tahdiya (calming, minor truce) or a hudna, a longer-term truce, obviously implies recognition. Khalid Mish’al states: ‘We are realists,’ and there is ‘an entity called Israel,’ but ‘realism does not mean that you have to recognise the legitimacy of the occupation.’

The war on Gaza has killed the two-state solution by making it clear to Palestinians that the only acceptable Palestine would have fewer rights than the Bantustans created by apartheid South Africa. The alternative, clearly, is a single state for Jews and Palestinians with equal rights for all. Certainly it seems utopian at the moment with the two Palestinian parties in Israel – Balad and the United Arab List – both barred from contesting the February elections. Avigdor Lieberman, the chairman of Yisrael Beiteinu, has breathed a sigh of satisfaction: ‘Now that it has been decided that the Balad terrorist organisation will not be able to run, the first battle is over.’ But even victory has its drawbacks. After the Six-Day War in 1967, Isaac Deutscher warned his one-time friend Ben Gurion: ‘The Germans have summed up their own experience in the bitter phrase “Mann kann sich totseigen!” — you can triumph yourself to death. This is what the Israelis have been doing. They have bitten off much more than they can swallow.’

Five hundred courageous Israelis have sent a letter to Western embassies calling for sanctions and other measures to be applied against their country, echoing the 2005 call by numerous Palestinian organisations for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) on the South African model. This will not happen overnight but it is the only non-violent way to help the struggle for freedom and equality in Israel-Palestine.

Tariq Ali’s latest book is The Duel: Pakistan on the Flight Path of American Power.

David Bromwich

Like the suicide bombings of the Second Intifada, the rockets from Gaza were a choice of tactics of a spectacular vengefulness. The spectacle was greater than the damage: no Israeli had been killed by a rocket before the IDF launched their assault. Yet the idea of rockets falling induces terror, whereas the idea of an army invading a neighbouring territory has an official sound. The numbers of the dead – as of 15 January, more than 1000 Palestinians and fewer than 20 Israelis – tell a different story. Many people remain unmoved by the tremendous disproportion because they cannot get the image of rockets out of their heads.

In the United States, since this one-sided war began on 27 December, facts are not suppressed but fiction pervades the commentary. We are offered an analogy: what would Americans do if rockets were fired from Canada or Cuba? The question has been repeated with docility by congressional leaders of both parties; but the rockets are assumed to come suddenly without cause. The choking of the Gaza Strip by land, sea and air, the rejection by the US of the Palestinian Unity Government, the coup launched by Fatah and bankrolled by the US, which ended in the seizure of power by Hamas – all of this happened before the rockets fell from the sky. It is as if it belonged to a prehistoric time.

American politicians exhibit an identification with Israel that is now in excess of the measurable effects of the Israel lobby. The blindness of the identification has led the US to respond with keen sensitivity to Israeli requests for assistance and moral support, and to underestimate the suffering caused by the Gaza blockade and by the settlements and checkpoints and the wall on the West Bank. Yet grant the potency of the lobby and the identification – even so, the arrogance with which Israel dictates policy is hard to comprehend on the usual index of motives. Ehud Olmert boasted to a crowd in Ashkelon on 12 January that with one phone call to Bush, he forced Condoleezza Rice to abstain from voting for the UN ceasefire resolution she herself had prepared. The depth, the efficacy and the immediacy of the influence are treated by Olmert as an open secret.

To judge by the nomination of Hillary Clinton as secretary of state, Obama wants to be seen as someone who intends no major change of course. In a televised interview on 11 January, he said he would deal with Israel and Palestine in the manner of the Clinton and Bush administrations. The unhappy message of his recent utterances has been reconciliation without truth; and reconciliation, above all, for Americans. This preference for bringing-together over bringing-to-light is a trait of Obama’s political character we are only now coming to see the extent of. It is an element – until lately an unperceived element – of a certain native moderation of temper that is likely to mark his presidency. Yet his silence on Gaza has been startling, even immoderate. The ascent of Barack Obama was connected in the world as well as in the US with peculiar and passionate hopes, and his chances of emerging as a leader of the world are diminished with every passing day of silence.

David Bromwich teaches English at Yale.

Alastair Crooke

‘We have to ask the West a question: when the Israelis bombed the house of Sheikh Nizar Rayan, a Hamas leader, killing him, his wives, his nine children, and killing 19 others who happened to live in adjoining houses – because they saw him as a target – was this terrorism? If the West’s answer is that this was not terrorism, it was self-defence – then we must think to adopt this definition too.’

This was said to me by a leading Islamist in Beirut a few days ago. He was making a point, but behind his rhetorical question plainly lies the deeper issue of what the Gaza violence will signify for mainstream Islamists in the future.

Take Egypt. Mubarak has made no secret of his wish to see Israel teach Hamas a ‘lesson’. Hamas are sure that his officials urged Israel to proceed, assuring Amos Yadlin, Israel’s Head of Military Intelligence, at a meeting in Cairo that Hamas would collapse within three days of the Israeli onslaught.

Islamists in Egypt and other pro-Western ‘moderate’ alliance states such as Saudi Arabia and Jordan have noted Israel’s wanton disregard for the deaths of civilians in its desire to crush Hamas. They have seen the barely concealed pleasure of the regimes that run those states. The message is clear: the struggle for the future of this region is going to be uncompromising and bloody.

For all Islamists, the events in Gaza will be definitive: they will tell the story of a heroic stand in the name of justice against impossible odds. This archetype was already in place on the day of Ashura – which fell this year on 7 January — when Shi’ites everywhere commemorate the martyrdom of Hussein, the Prophet’s grandson, killed by an overwhelming military force at Kerbala. The speeches given by Hassan Nasrallah, Hizbullah’s secretary general, were avidly followed; the ceremony of Ashura drove home the message of martyrdom and sacrifice.

Islamists are likely to conclude from Gaza that Arab regimes backed by the US and some European states will go to any lengths in their struggle against Islamism. Many Sunni Muslims will turn to the salafi-jihadists, al-Qaida included, who warned Hamas and others about the kind of punishment being visited on them now. Mainstream movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood, Hamas and Hizbullah will find it hard to resist the radical trend. The middle ground is eroding fast.

At one level Gaza will be seen as a repeat of Algeria. At another, it will speak to wider struggles in the Arab world, where elites favoured by the West soldier on with no real legitimacy, while the weight of support for change builds up. The overhang may persist for a while yet, but a small event could trip the avalanche.

Alastair Crooke is co-director of Conflicts Forum and has been an EU mediator with Hamas and other Islamist movements. Resistance: The Essence of the Islamist Revolution will come out next month.

Conor Gearty

It is just possible the killings in Gaza may mark the end of Israel’s disastrous plunge into militant Zionism. The key is Obama: will he collapse under pressure like most of his predecessors, or is there more to him? Let us assume he knows how senseless it is for the US to collude in a crime of the kind going on in Gaza. There are ways of marking this without unleashing the pro-Israeli forces against him at too early a stage.

Clearly the new administration desires to re-engage with the global community and revive its commitment to international law: the ‘war on terror’ will be reconfigured and Guantanamo closed. A rededication of the US to law should also involve a more consensual approach to the UN – Security Council business in particular – including (for example) support for UN investigative missions to regions where egregious violations of human rights and breaches of the UN charter have occurred. It should entail the US signing up to the International Criminal Court – and urging its closest allies to do likewise. Framed in this way, a US engagement in the international human rights agenda would quickly lead to a crucial re-empowerment of the rapporteurs, special representatives, committees of experts and so on who have languished on the margins for so long.

This reformist energy would then need to be backed by mechanisms along the lines of the MacBride principles or the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act linking US financial and military aid to the newly emerging international legal order. The worst offenders against the new dispensation would run the risk of economic and intellectual boycotts. Since its application would be general, Obama could do all this without any mention of Israel, leaving the consequences to be worked through by various bureaucracies, while the phone calls and special pleas are politely fended off with an easy ‘it is out of my hands’. Were pressure from the lobbies to reach dangerous levels, the president might choose to take the issue to the American people, to discuss openly whether Israel should have an exemption from the system of values to which every other genuine ally and the US itself will by then have signed up. That is not likely to be a debate which the Israeli leadership will want.

Conor Gearty, Rausing Director of the Centre for the Study of Human Rights and professor of human rights law at the LSE, has written a number of books on terrorism and human rights.

Eric Hobsbawm

For three weeks barbarism has been on show before a universal public, which has watched, judged and with few exceptions rejected Israel’s use of armed terror against the one and a half million inhabitants blockaded since 2006 in the Gaza Strip. Never have the official justifications for invasion been more patently refuted by the combination of camera and arithmetic; or the newspeak of ‘military targets’ by the images of bloodstained children and burning schools. Thirteen dead on one side, 1360 on the other: it isn’t hard to work out which side is the victim. There is not much more to be said about Israel’s appalling operation in Gaza.

Except for those of us who are Jews. In a long and insecure history as a people in diaspora, our natural reaction to public events has inevitably included the question: ‘Is it good or bad for the Jews?’ In this instance the answer is unequivocally: ‘Bad for the Jews’.

It is patently bad for the five and a half million Jews who live in Israel and the occupied territories of 1967, whose security is jeopardised by the military actions that Israeli governments take in Gaza and in Lebanon; actions which demonstrate their inability to achieve their declared aims and which perpetuate and intensify Israel’s isolation in a hostile Middle East. Since genocide or the mass expulsion of Palestinians from what remains of their native land is no more on the practical agenda than the destruction of the state of Israel, only negotiated coexistence on equal terms between the two groups can provide a stable future. Each new military adventure, like the ones in Gaza and Lebanon, will make such a solution more difficult and will strengthen the hand of the Israeli right wing and the West Bank settlers who do not want it in the first place.

Like the war in Lebanon in 2006, Gaza has darkened the outlook for the future of Israel. It has also darkened the outlook for the nine million Jews who live in the diaspora. Let me not beat about the bush: criticism of Israel does not imply anti-semitism, but the actions of the government of Israel occasion shame among Jews and, more than anything else, they give rise to anti-semitism today. Since 1945 the Jews, inside and outside Israel, have enormously benefited from the bad conscience of a Western world that had refused Jewish immigration in the 1930s before committing or failing to resist genocide. How much of that bad conscience, which virtually eliminated anti-semitism in the West for sixty years and produced a golden era for its diaspora, is left today?

Israel in action in Gaza is not the victim people of history, nor even the ‘brave little Israel’ of 1948-67 mythology, a David defeating all its surrounding Goliaths. Israel is losing goodwill as rapidly as the US did under George W. Bush, and for similar reasons: nationalist blindness and the megalomania of military power. What is good for Israel and what is good for the Jews as a people are evidently linked, but, until there is a just answer to the Palestinian question, they are not and cannot be identical. And it is essential for Jews to say so.

Eric Hobsbawm’s most recent book is Globalisation, Democracy and Terrorism.

R.W. Johnson

The current crisis has probably not changed anything fundamental. As even the more pessimistic Israeli analysts have been noting for some time, the pressure of the crisis has turned many, perhaps most Palestinians into irreconcilable foes of Israel. To that extent the two-state solution, however much the great and good may wish it, gradually becomes less and less of a real solution. The present crisis was probably unavoidable given (a) Iran’s position, (b) the coming Israeli election and (c) the failure of Israel to achieve full-scale victory over Hizbullah last year. That last factor has weighed on all minds, showing Iran how much leverage it had, threatening to turn all Arab-occupied land into rocket-launching grounds and increasing Israeli determination to show that this is a prohibitively expensive option for anyone who opts to host such an exercise. The stalemate seems complete.

I doubt whether Obama will make much difference. His chief of staff is an ex-Israeli soldier and his administration will be heavily in hock to the Israel lobby from day one. Israel may be unhappy that he will talk to Hamas but this unhappiness is quite unnecessary. He is not going to soft-talk them into accepting Israel’s existence and laying down their rockets, so what will such talks really change?

The real key remains US-Iran relations. This was a period in which many expected an Israeli strike against Iranian nuclear facilities. The fact that it has not happened is promising and suggests that the CIA is right to say Iran is not close to having nuclear weapons. As it is the US has hugely strengthened Iran by handing Iraq over to Shi’ites and an Obama administration might try to capitalise on that by making a US-Iranian deal the cornerstone of Middle East politics, thus reducing Syrian, Saudi and Egyptian leverage. Iran would obviously be greatly tempted by such a deal. But if Obama and Ahmadinejad really could reach a deal it would probably be very bad news for both Hizbullah and Hamas, who might get cut off from Iranian aid. If that happens, I can’t see much joy for Palestinian militancy. But if it doesn’t and the US under Obama is left to face an unchanged position, he is bound to end up taking Israel’s side as much as Bush did. Which also doesn’t bode well for militant Palestinians. So whatever happens I’d expect the Palestinians to emerge worse off from this conflict and Israel stronger, though probably less popular.

R.W. Johnson lives in Cape Town.

Rashid Khalidi

It is commonplace to talk about the ‘fog of war’, but war can also clarify things. The war in Gaza has pointed up the Israeli security establishment’s belief in force as a means of imposing ‘solutions’ which result in massive Arab civilian suffering and solve nothing. It has also laid bare the feebleness of the Arab states, and their inability to protect Palestinian civilians from the Israeli military, to the despair and fury of their citizens. Almost from the moment the war began, America’s Arab allies – above all Egypt – found themselves on the defensive, facing accusations of impotence and even treason in some of the largest demonstrations the region has seen in years. Hassan Nasrallah, the secretary general of Hizbullah in Lebanon, reserved some of his harshest criticism for the Mubarak regime; at Hizbullah rallies, protesters chanted ‘Where are you, Nasser?’ – a question that is also being asked by Egyptians.

The Egyptian government and its Arab allies – Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Morocco – responded to the war much as they responded to the 2006 invasion of Lebanon: by tacitly supporting Israel’s offensive in the hope of weakening a resistance movement which they see as a proxy for Iran and Syria. When the bombing began, Egypt criticised Hamas over the breakdown of the reconciliation talks with Fatah that Cairo had brokered, and for firing rockets at Israel. The implication was that Hamas was responsible for the war. Refusing to open the Rafah crossing, the Mubarak government pointed out that Israel, the occupying power, not Egypt, was responsibile for the humanitarian situation in Gaza under the Fourth Geneva Convention. Egypt’s concern is understandable: ever since it recovered the Sinai in 1982, it has worried that Israel might attempt to dump responsibility onto it for the Strip’s 1.5 million impoverished residents, a fear that has grown as the prospects of ending the occupation have receded. But its initial refusal to open the crossing to relief supplies, medical personnel and reporters made it difficult for Cairo to deny charges that it was indifferent to Palestinian suffering, and that it valued relations with Israel and the US (its main patron) more highly than the welfare of Gaza’s people.

Since Hamas came to power in Gaza in 2006, Egypt’s press has been rife with lurid warnings – echoed in conservative Lebanese and Saudi newspapers, as well as Israeli ones – about the establishment in Gaza of an Islamic emirate backed by Iran. Cairo’s distrust of Hamas is closely connected with internal politics: Hamas is an offshoot of the Muslim Brothers, the country’s largest opposition movement; and it came to power in Gaza in the kind of democratic elections that Mubarak has done everything to prevent. (He is likely to be succeeded by his son, Gamal, after sham elections.) When there still seemed hope of a Palestinian Authority (PA) coalition government between Fatah and Hamas (which would have diluted the latter’s power), Egypt was careful to appear balanced. But after the deep split in Palestinian politics that followed the Hamas takeover of Gaza in 2007, Egypt tilted increasingly against Hamas. The division of occupied Palestine into two PAs – a Fatah-ruled West Bank and a Hamas-ruled Gaza Strip, both without sovereignty, jurisdiction or much in the way of authority – was seen in Cairo as a threat to domestic security: it promised greater instability on Egypt’s borders, jeopardised the negotiated two-state solution with Israel to which Egypt was committed, and emboldened allies of the Muslim Brothers.

Egypt has also been alarmed by Hamas’s deepening relationship with its fiercest adversaries: Iran, Syria and Hizbullah. ‘Moderate’ Arab regimes like the one in Egypt – deeply authoritarian, at best, but friendly with the US – have favoured peaceful negotiations with Israel, but negotiations have not led to Palestinian independence, or even translated into diplomatic leverage. Resistance movements such as Hizbullah and Hamas, by contrast, can plausibly claim that they forced Israel to withdraw from occupied Arab land while scoring impressive gains at the ballot box; they have also been reasonably free of corruption. As if determined to increase the influence of these radical movements, Israel has undermined Abbas and the PA at every turn: settlements, bypass roads and ‘security barriers’ continue to encroach on Palestinian land; none of the 600 checkpoints and barriers in the West Bank has been removed; and more than 10,000 Palestinian political prisoners languish in Israeli jails. The result has been the erosion of support for the PA, and for the conciliatory approach pursued by the PA and Arab states such as Egypt and Saudi Arabia, which reacted by moving even closer to the Bush administration in its waning days. Mubarak, according to Ha’aretz, urged Olmert to continue the Gaza offensive until Hamas was severely weakened – though Egypt has, of course, denied these reports.

But Hamas will not be so easily defeated, even if Israel’s merciless assault and Hamas’s own obduracy have brought untold suffering on the people of Gaza and much of the Strip lies in ruins: like Hizbullah in Lebanon in 2006, all it has to do in order to proclaim victory is remain standing. The movement continued to fire rockets into Israel under devastating bombardment, and it looks likely to emerge politically stronger when the war is over, although as with Hizbullah, it may have provoked popular resentment for bringing Israeli fire down on the heads of the civilian population: there was little Palestinian popular support for the firing of rockets at Israel in the months before the Israeli offensive. It is doubtful, moreover, whether any Hamas leader will be as shrewd as Hassan Nasrallah after the 2006 Lebanon war, when he admitted that had he known the damage Israel would do, he would not have offered the pretext that triggered its onslaught.

Israel began a propaganda campaign several months ago, when it closed Gaza to journalists in what appears to have been an effort to remove witnesses from the scene before the crime took place. Cell phone transmission was interrupted to prevent the circulation of photos and videos. The result, in Israel and the US, has been an astonishingly sanitised war, in which, in a bizarre attempt at ‘balance’, the highly inaccurate rocket attacks against Israel and their three civilian victims since the fighting began on 27 December have received as much attention as the levelling of Gaza and the killing of more than 1000 Palestinians and the wounding of nearly 5000, most of them civilians. But Arabs and Muslims (and indeed most people not living in the US and Israel) have seen a very different war, with vivid images of those trapped in the Gaza Strip, thanks in large part to Arab journalists on the ground.

During the large demonstrations that erupted in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Jordan and Yemen, condemnation was directed not only at the usual targets, Israel and the US, but also at the passivity, even complicity, of Arab governments. Stung by the protests and fearing popular unrest, several Arab states sent their foreign ministers to New York, led by Prince Sa’ud al-Faisal, the Saudi foreign minister, and forced through a Security Council resolution in the face of American resistance. Jordan withdrew its ambassador from Tel Aviv; Qatar broke off ties with Israel and offered $250 million for the rebuilding of Gaza. At the same time, Egypt made limited concessions, taking some wounded Gazans to hospitals in Egypt, providing medical supplies, and belatedly allowing a few medical personnel into the Strip through the Rafah crossing. Yet the Mubarak regime has otherwise continued to play the role of even-handed mediator.

As I write, its proposals for a ceasefire have met with a positive response from both Hamas (which has significantly modulated its criticism of Egypt) and Israel. It is still unclear how Egypt will respond to Israel’s demands that it halt arms smuggling through tunnels into Gaza; when and if the crossings will be fully opened; under what arrangements, and how reconstruction aid will be channelled to the devastated area; and indeed how an Egyptian-brokered arrangement, should it come into force and endure, will be regarded by Egyptian and Arab public opinion.

For the moment, the shaky legitimacy of Abbas’s government in Ramallah, and of the authoritarian Arab governments that have cast their lot with Israel and the United States in the regional contest with Iran, appears to have grown shakier still. Should Iran and Syria succeed in rapidly establishing new relationships with Washington under the Obama administration, these governments will be further weakened. Moreover, their inability (or their unwillingness) to do more to resolve the Palestine question, or even to alleviate Palestinian suffering, has been exposed once again. It contrasts starkly with democratic and non-Arab Turkey’s robust support for the Palestinians. Palestine has been a rallying cry for opposition movements in the Arab world since 1948, and in the decade after the first Arab-Israeli war a series of domestic upheavals, revolutions and coups took place in several Arab countries, including Egypt, where veterans of the Palestine war led by Nasser came to power in the 1952 coup against King Farouk. The repressive capacities of a government such as Egypt’s, whose secret police is said to employ more than a million people, should not be underestimated. But several unpopular regimes may face serious consequences at home for having aligned themselves with Israel.

Rashid Khalidi is Edward Said Professor of Arab Studies at Columbia.

Yitzhak Laor

We’ve been here before. It’s a ritual. Every two or three years, our military mounts another bloody expedition. The enemy is always smaller, weaker; our military is always larger, technologically more sophisticated, prepared for full-scale war against a full-scale army. But Iran is too scary, and even the relatively small Hizbullah gave us a hard time. That leaves the Palestinians.

Israel is engaged in a long war of annihilation against Palestinian society. The objective is to destroy the Palestinian nation and drive it back into pre-modern groupings based on the tribe, the clan and the enclave. This is the last phase of the Zionist colonial mission, culminating in inaccessible townships, camps, villages, districts, all of them to be walled or fenced off, and patrolled by a powerful army which, in the absence of a proper military objective, is really an over-equipped police force, with F16s, Apaches, tanks, artillery, commando units and hi-tech surveillance at its disposal.

The extent of the cruelty, the lack of shame and the refusal of self-restraint are striking, both in anthropological terms and historically. The worldwide Jewish support for this vandal offensive makes one wonder if this isn’t the moment Zionism is taking over the Jewish people.

But the real issue is that since 1991, and even more since the Oslo agreements in 1993, Israel has played on the idea that it really is trading land for peace, while the truth is very different. Israel has not given up the territories, but cantonised and blockaded them. The new strategy is to confine the Palestinians: they do not belong in our space, they are to remain out of sight, packed into their townships and camps, or swelling our prisons. This project now has the support of most of the Israeli press and academics.

We are the masters. We work and travel. They can make their living by policing their own people. We drive on the highways. They must live across the hills. The hills are ours. So are the fences. We control the roads, and the checkpoints and the borders. We control their electricity, their water, their milk, their oil, their wheat and their gasoline. If they protest peacefully we fire tear gas at them. If they throw stones, we fire bullets. If they launch a rocket, we destroy a house and its inhabitants. If they launch a missile, we destroy families, neighbourhoods, streets, towns.

Israel doesn’t want a Palestinian state alongside it. It is willing to prove this with hundreds of dead and thousands of disabled, in a single ‘operation’. The message is always the same: leave or remain in subjugation, under our military dictatorship. We are a democracy. We have decided democratically that you will live like dogs.

On 27 December just before the bombs started falling on Gaza, the Zionist parties, from Meretz to Yisrael Beiteinu, were unanimously in favour of the attack. As usual – it’s the ritual again – differences emerged only over the dispatch of blankets and medication to Gaza. Our most fervent pro-war columnist, Ari Shavit, has suggested that Israel should go on with the assault and build a hospital for the victims. The enemy is wounded, bleeding, dying, desperate for help. Nobody is coming unless Obama moves – yes, we are all waiting for Godot. Maybe this time he shows up.

Yitzhak Laor lives in Tel Aviv. He is the editor of Mita’am.

John Mearsheimer

The Gaza war is not going to change relations between Israel and the Palestinians in any meaningful way. Instead, the conflict is likely to get worse in the years ahead. Israel will build more settlements and roads in the West Bank and the Palestinians will remain locked up in a handful of impoverished enclaves in Gaza and the West Bank. The two-state solution is probably dead.

‘Greater Israel’ will be an apartheid state. Ehud Olmert has sounded a warning note on this score, but he has done nothing to stop the settlements and by starting the Gaza war he doomed what little hope there was for creating a viable Palestinian state.

The Palestinians will continue to resist the occupation, and Hamas will still be able to strike Israel with rockets and mortars, whose range and effectiveness are likely to improve. Palestinians will increasingly make the case that Greater Israel should become a democratic binational state in which Palestinians and Jews enjoy equal political rights. They know that they will eventually outnumber the Jews, which would mean the end of Israel as a Jewish state. This proposal is already gaining ground among Israel’s Palestinian citizens, striking fear into the hearts of many Israelis, who see them as a dangerous fifth column. This fear accounts in part for the recent Israeli decision to ban the major Arab political parties from participating in next month’s parliamentary elections.

There is no reason to think that Israel’s Jewish citizens would accept a binational state, and it’s safe to assume that Israel’s supporters in the diaspora would have no interest in it. Apartheid is not a solution either, because it is repugnant and because the Palestinians will continue to resist, forcing Israel to escalate the repressive policies that have already cost it significant blood and treasure, encouraged political corruption, and badly tarnished its global image.

Israel may try to avoid the apartheid problem by expelling or ‘transferring’ the Palestinians. A substantial number of Israeli Jews – 40 per cent or more – think that the government should ‘encourage’ their fellow Palestinian citizens to leave. Indeed, Tzipi Livni recently said that if there is a two-state solution, she expects the Palestinians inside Israel to move to the new Palestinian state.

Why would American and European leaders intervene? The Bush administration, after all, backed Israel’s creation of a major humanitarian crisis in Gaza, first with a devastating blockade and then with a brutal war. European leaders reacted to this collective punishment, which violates international law, not to mention basic decency, by upgrading Israel’s relationship with the European Union.

Many in the West expect Barack Obama to ride into town and fix the situation. Don’t bet on it. As his campaign showed, Obama is no match for the Israel lobby. His silence during the Gaza war speaks volumes about how tough he is likely to be with the Israelis. And the lobby will keep constant pressure on Obama. After he’d selected George Mitchell to be his special envoy for the Israel-Palestinian conflict, Abraham Foxman, the powerful head of the Anti-Defamation League, criticised Mitchell for being ‘fair’ and ‘meticulously even-handed’: just the right qualities for the job, you might have thought, but not for Foxman, who demands that Obama and his lieutenants favour Israel over the Palestinians at every turn.

In a recent op-ed about the Gaza war, Benny Morris said that ‘it would not be surprising if more powerful explosions were to follow.’ I rarely agree with Morris these days, but I think he has it right in this case. Even bigger trouble is in the offing for Israel – and above all for the Palestinians.

John Mearsheimer is a professor of political science at the University of Chicago and co-author of The Israel Lobby and US Foreign Policy.

Yonatan Mendel

It’s very frustrating to see Israeli society recruited so calmly and easily to war. Hardly anyone has dared to mention the connection between the decision to go to war and the fact that we are only a few weeks away from an election. Kadima (Tzipi Livni’s party) and Labour (Ehud Barak’s) were doing very badly in the polls. Now that they have killed more than 1000 Palestinians (250 on the first day – the highest number in 41 years of occupation) they are both doing very well. Barak was expected to win eight seats in the Knesset; now it is around 15. Netanyahu is the one sweating.

I am terribly sad about all this, and frustrated. On the first day of the operation I wrote an article for the Walla News website and within four hours I had received 1600 comments, most calling for my deportation (at best) or immediate execution (at worst). It showed me again how sensitive Israeli society is to any opposition to war. It is shocking how easily this society unites behind yet another military solution, after it has failed so many times. Hizbullah was created in response to Israel’s occupation of Lebanon in 1982. Hamas was created in 1987 in response to two decades of military occupation. What do we think we’ll achieve this time?

The state called up more than 10,000 reservists, and even people who had not been called also travelled to military bases and asked to be sent to Gaza. This shows once again how efficient the Israeli propaganda and justification machine is, and how naturally people here believe in myths that have been disproved again and again. If people were saying, ‘We killed 1000 people, but the army is not perfect, and this is war,’ I would say it was a stupid statement. But Israelis are saying: ‘We killed 1000 people, and our army is the most moral army in the world.’ This says a lot about the psychology of the conflict: people are not being told what to think or say; they reach these insights ‘naturally’.

Since I was a soldier myself ten years ago, I worry I might be called up as a reservist. If I were to refuse now, when Israel is at war, I would be sent to prison. But still, I tell myself, that would be so much easier than being part of what my country is doing. Apparently, every single Jewish member of the Knesset, except one from the Jewish-Arab list, believes that killing more Palestinians, keeping the Gazan population under siege, destroying their police stations, ministerial offices and headquarters will weaken Hamas, strengthen Israel, demonstrate to the Palestinians that next time they should vote for Fatah, and bring stability to the region. I have no words. Only one Jewish member of the Knesset, out of 107, went to the demonstration that followed the deliberate bombing by the Israelis of an UNRWA school being used to house refugees, resulting in the deaths of 45 civilians. Once again, the Israeli slogan is ‘Let the IDF win’ and once again everybody agrees. People have short memories. By 2008, two years after the Second Lebanon War ended, Hizbullah had more soldiers than before, three times more weapons, and had dramatically improved its political position. It now even has a right of veto in parliament. The same could happen to Hamas, but once again military magic enchants Israeli society.

I have a friend whose brother is a pilot in the IDF. I asked to speak to him. I told him what I thought about Israel’s behaviour and he seemed to agree with my general conclusions. He said, however, that a soldier should not ask himself such questions, which should be kept to the political sphere. I can’t agree. But the second thing he told me was more important. He told me that for pilots, a day like the first day of the war, when so many attacks are being made simultaneously, is a day full of excitement, a day you look forward to. If you take these words into account, and bear in mind that in Israel every man is a soldier, either in uniform or in reserve, there is no avoiding the conclusion that there are great pressures for it to act as a military society. Not acting is damaging to the IDF’s status, budget, masculinity, power and happiness, and not only to the IDF’s. This could explain why in Israel the military option is almost never considered second best. It is always the first choice.

Ha’aretz too is a source of unhappiness for me, since in wartime the paper is part of this militaristic discourse, shares its values and lack of vision. Ha’aretz did not criticise Israel when its troops deployed to Lebanon in 2006. Nor did it have anything to say when the same soldiers bombed Gaza’s police, schools and people. Even when there was a demonstration against the war, with more than 10,000 people taking part, both Jews and Palestinian citizens of Israel, the Ha’aretz website chose to publish a picture of a counter-demonstration, in which a few hundred participated, waving Israeli flags and shouting: ‘Let the IDF win.’

I have problems speaking to my closest friends and family these days, because I can no longer bear to hear the security establishment’s propaganda coming from their mouths. I cannot bear to hear people justifying the deaths of more than 200 children killed by Israeli soldiers. There is no justification for that, and it’s wrong to try to find one. Usually I feel part of society in Israel. I feel that I am on one side of the political map and other people are on the opposite side. But over the last few days, I feel that I am not part of this society any more. I do not call friends who support the war, and they do not call me. The same with my family. It is a hard thing for me to write, but this is how it is.

Yonatan Mendel was a correspondent for the Israeli news agency Walla. He is currently at Queens’ College, Cambridge working on a PhD that studies the connection between the Arabic language and security in Israel.

Ilan Pappe

In 2004, the Israeli army began building a dummy Arab city in the Negev desert. It’s the size of a real city, with streets (all of them given names), mosques, public buildings and cars. Built at a cost of $45 million, this phantom city became a dummy Gaza in the winter of 2006, after Hizbullah fought Israel to a draw in the north, so that the IDF could prepare to fight a ‘better war’ against Hamas in the south.

When the Israeli Chief of General Staff Dan Halutz visited the site after the Lebanon war, he told the press that soldiers ‘were preparing for the scenario that will unfold in the dense neighbourhood of Gaza City’. A week into the bombardment of Gaza, Ehud Barak attended a rehearsal for the ground war. Foreign television crews filmed him as he watched ground troops conquer the dummy city, storming the empty houses and no doubt killing the ‘terrorists’ hiding in them.

‘Gaza is the problem,’ Levy Eshkol, then prime minister of Israel, said in June 1967. ‘I was there in 1956 and saw venomous snakes walking in the street. We should settle some of them in the Sinai, and hopefully the others will immigrate.’ Eshkol was discussing the fate of the newly occupied territories: he and his cabinet wanted the Gaza Strip, but not the people living in it.

Israelis often refer to Gaza as ‘Me’arat Nachashim’, a snake pit. Before the first intifada, when the Strip provided Tel Aviv with people to wash their dishes and clean their streets, Gazans were depicted more humanely. The ‘honeymoon’ ended during their first intifada, after a series of incidents in which a few of these employees stabbed their employers. The religious fervour that was said to have inspired these isolated attacks generated a wave of Islamophobic feeling in Israel, which led to the first enclosure of Gaza and the construction of an electric fence around it. Even after the 1993 Oslo Accords, Gaza remained sealed off from Israel, and was used merely as a pool of cheap labour; throughout the 1990s, ‘peace’ for Gaza meant its gradual transformation into a ghetto.

In 2000, Doron Almog, then the chief of the southern command, began policing the boundaries of Gaza: ‘We established observation points equipped with the best technology and our troops were allowed to fire at anyone reaching the fence at a distance of six kilometres,’ he boasted, suggesting that a similar policy be adopted for the West Bank. In the last two years alone, a hundred Palestinians have been killed by soldiers merely for getting too close to the fences. From 2000 until the current war broke out, Israeli forces killed three thousand Palestinians (634 children among them) in Gaza.

Between 1967 and 2005, Gaza’s land and water were plundered by Jewish settlers in Gush Katif at the expense of the local population. The price of peace and security for the Palestinians there was to give themselves up to imprisonment and colonisation. Since 2000, Gazans have chosen instead to resist in greater numbers and with greater force. It was not the kind of resistance the West approves of: it was Islamic and military. Its hallmark was the use of primitive Qassam rockets, which at first were fired mainly at the settlers in Katif. The presence of the settlers, however, made it hard for the Israeli army to retaliate with the brutality it uses against purely Palestinian targets. So the settlers were removed, not as part of a unilateral peace process as many argued at the time (to the point of suggesting that Ariel Sharon be awarded the Nobel peace prize), but rather to facilitate any subsequent military action against the Gaza Strip and to consolidate control of the West Bank.

After the disengagement from Gaza, Hamas took over, first in democratic elections, then in a pre-emptive coup staged to avert an American-backed takeover by Fatah. Meanwhile, Israeli border guards continued to kill anyone who came too close, and an economic blockade was imposed on the Strip. Hamas retaliated by firing missiles at Sderot, giving Israel a pretext to use its air force, artillery and gunships. Israel claimed to be shooting at ‘the launching areas of the missiles’, but in practice this meant anywhere and everywhere in Gaza. The casualties were high: in 2007 alone three hundred people were killed in Gaza, dozens of them children.

Israel justifies its conduct in Gaza as a part of the fight against terrorism, although it has itself violated every international law of war. Palestinians, it seems, can have no place inside historical Palestine unless they are willing to live without basic civil and human rights. They can be either second-class citizens inside the state of Israel, or inmates in the mega-prisons of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. If they resist they are likely to be imprisoned without trial, or killed. This is Israel’s message.

Resistance in Palestine has always been based in villages and towns; where else could it come from? That is why Palestinian cities, towns and villages, dummy or real, have been depicted ever since the 1936 Arab revolt as ‘enemy bases’ in military plans and orders. Any retaliation or punitive action is bound to target civilians, among whom there may be a handful of people who are involved in active resistance against Israel. Haifa was treated as an enemy base in 1948, as was Jenin in 2002; now Beit Hanoun, Rafah and Gaza are regarded that way. When you have the firepower, and no moral inhibitions against massacring civilians, you get the situation we are now witnessing in Gaza.

But it is not only in military discourse that Palestinians are dehumanised. A similar process is at work in Jewish civil society in Israel, and it explains the massive support there for the carnage in Gaza. Palestinians have been so dehumanised by Israeli Jews – whether politicians, soldiers or ordinary citizens – that killing them comes naturally, as did expelling them in 1948, or imprisoning them in the Occupied Territories. The current Western response indicates that its political leaders fail to see the direct connection between the Zionist dehumanisation of the Palestinians and Israel’s barbarous policies in Gaza. There is a grave danger that, at the conclusion of ‘Operation Cast Lead’, Gaza itself will resemble the ghost town in the Negev.

Ilan Pappe is chair of the history department at the University of Exeter and co-director of the Exeter Centre for Ethno-Political Studies. The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine came out in 2007.

Gabriel Piterberg

Israel’s onslaught on Gaza may well do permanent damage to one of the most effective tools in its propaganda kit: the image of the morally handsome, ‘shooting and crying’ Israeli soldier.

Three weeks after the 1967 War, Avraham Shapira and Amos Oz, then a rising young author, were summoned to Labour Party headquarters. They were asked to make the demobilised soldiers from the kibbutzim break the wall of silence and discuss their war experience. Soldiers’ Talk (Siah Lohamim), the collection of interviews they edited, was a national and international success. The book, which forged the image of the handsome, dilemma-ridden, existentially soul-searching Israeli soldier, was a hymn to that frightening oxymoron, ‘purity of arms’ and the ideal of an exalted Jewish morality.

It was also a kind of ‘central casting’ from which Oz drew many of his fictional protagonists. Rabin (when he was ambassador to Washington) and Elie Wiesel read extracts in the US ‘in order to present the Israeli soldier’s profile’; and Golda Meir called it ‘a sacred book’: ‘we are fortunate to have been blessed with such sons.’ The latest version of Soldiers’ Talk, in terms of register and success, is Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir.

Given the might of Israel’s warriors and the vulnerability of their targets, now that the country no longer engages in wars against other state armies, the image is hard to keep alive. At the same time it no longer matters in the way it once did: for political and military elites in Israel, and the War on Terror constituency in the US, the killing of Arabs and Muslims no longer requires any weeping or soul-searching. It’s just what freedom-loving people do. The war adulation of the recent pro-Israel demonstrations in Los Angeles is chastening but you couldn’t call it hypocritical.

Perhaps with the benefit of hindsight, the attack on Gaza will be seen as the action of a colonial power that is running out of ideas; not unlike France in the final stage of the Algerian war.

Gabriel Piterberg teaches history at UCLA. The Returns of Zionism was published last year.

Jacqueline Rose

The only abiding law for Israel in this onslaught seems to be the ethics of self-defence, and yet Israel’s defence cannot be secured by such a path and there are, it would seem, no ethics. How can such unrestrained and indiscriminate violence – a hundred, and more, dead for every Israeli, including hundreds of children – be justified? ‘We are very violent,’ the commander of the Yahalom unit observed, according to Ha’aretz. ‘We do not balk at any means to protect the lives of our soldiers.’ Another senior IDF officer was reported as commenting on the offensive so far, ‘It’s not the movie, it’s only the coming attractions,’ with a knowing smile.

If it sometimes seems as if a new limit has been breached, we need to trace this language back to the creation of Israel and before, to the founding belief that Israel would be the redemption for the historic suffering, and passivity, of the Jews, a belief given new urgency by the genocide in Europe and which would lay the grounds for the ruthless dispossession of the Palestinians. At a rally in support of Israel’s war in Gaza in Trafalgar Square, one banner read: ‘We will not be victims again.’ As the rally dispersed, those of us protesting as Jews against Israel’s actions were spat at and met with cries of ‘Kapos’. The Holocaust is still the felt justification, in the midst of this new war. Israel is the fourth most powerful military nation in the world, yet it lives in a permanent state of fear, always fighting the last war.

So while everyone is asking ‘Who is the aggressor?’, another equally important question is going unasked. Who claims the monopoly of suffering? Whose suffering is felt to warrant a form of state power that is above the law? Already we are being told that there will be no legal reckoning. Faced with war crimes allegations in the past, Israel has blocked all attempts by the UN to investigate its conduct and it is not a signatory to the International Criminal Court.

To say this is in no way to diminish the traumatic impact of the Holocaust but to register it all the more powerfully. The effect of trauma is precisely to freeze people in time. There is a psychological dimension to this conflict that seems almost impossibly difficult to shift. In its own eyes, Israel is never the originator and agent of its own violence, and to that extent its violence is always justified. The Palestinians do not count. Even when the worst of what has been done to them is registered inside Israel, it is still the Israeli who suffers more.

We are all waiting to see what Barack Obama will do. My hope is that he is ring-fencing his new appointees (Rahm Emanuel and Hillary Clinton) so he can intervene more forcefully to change the US’s unconditional support for Israel. But even if he were to do so early on, a single breach of any agreement by Hamas – even if, as most likely, provoked by Israel – might be enough for him to adopt Israel’s language of state security as the justification of all means. ‘As soon as anyone mentions security,’ Miri Weingarten of Physicians for Human Rights commented on a visit last year to Britain, ‘everyone stands up straight and stops thinking.’

Jacqueline Rose is a co-founder of Independent Jewish Voices.

Eliot Weinberger

1. Who remembers the original dream of Israel? A place where the observant could practice their religion in peace and the secular would be invisible as Jews – where being Jewish only mattered if you wanted it to matter. That dream was realised, not in Israel, but in New York City.

2. The second dream of Israel was of a place where socialist collectives could flourish in a secular nation with democratic freedoms. Who remembers that now?

3. ‘Never again’ should international Jews invoke the Holocaust as justification for Israeli acts of barbarism.

4. As in India-Pakistan, blaming the Brits is true enough, but useless.

5. A few days ago, to illustrate the Gaza invasion, the front page of the New York Times had a large pastoral photograph of handsome Israeli soldiers lounging on a hill above verdant fields. Unquestioning faith in the ‘milk and honey’ Utopia of Israel is the bedrock of American Judaism, and reality does not intrude on faith.

6. Any hope for some sort of peace will not come from the US, even without Bush. It must come from within an Israel where the same petrified leaders are elected time and again, where masses of the rational have emigrated to saner shores and have been replaced by Russians and the American cultists who become settlers. It is hard to believe that this will be anytime soon.

7. It is hard to believe that two states will ever be possible. So why not a new dream of Israel? A single nation, a single citizenry with equal rights, three languages– English as a neutral third – and three religions, separate from the state. Give it a new name – say, Semitia, land of the Semites.

Eliot Weinberger’s recent books include What Happened Here: Bush Chronicles.

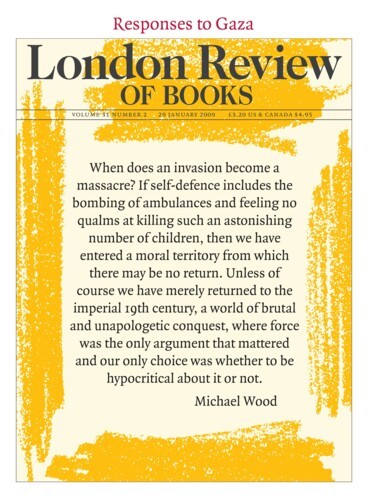

Michael Wood

A New York Times reporter describes the ‘lethal tricks’ of Hamas in Gaza. I don’t doubt the existence of the tricks, but the implication is that the far more lethal directness of the Israeli attack is not only justified but morally superior to the enemy’s underhand modes of action. This is an adaptation of an old paradigm, in which Israel gets to play the role of the rational modern state. The straightforward, civilised West meets the endlessly devious, backward Orient, and takes care of things in its up-to-date efficient way. What’s wrong with that? They are always ‘they’; their deaths don’t count as ours do.

When does an invasion become a massacre? How many Palestinians have to die just because they are Palestinians before we recognise another old paradigm? Herzl thought the native population of what was to become Israel would have to be ‘spirited’ across the border; now the very deaths of that population are being spirited off into arguments about the right to self-defence. If self-defence includes the bombing of ambulances and feeling no qualms at killing such an astonishing number of children, then we have entered a moral territory from which there may be no return. Unless of course we have merely returned to the imperial 19th century, a world of brutal and unapologetic conquest, where force was the only argument that mattered and our only choice was whether to be hypocritical about it or not.

Michael Wood teaches at Princeton. His most recent book is Literature and the Taste of Knowledge.

These responses were updated on 23 January

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.