One evening a few months ago when Clinton was still President, I found myself in a dive on Eighth Avenue between 41st and 42nd Street. A Democratic Congressman, ‘a friend of the people of Kashmir’, was addressing a meeting of Kashmiri Muslims. Recently returned from a visit to the country, he had been ‘deeply moved’ by the suffering he had witnessed and was now convinced that ‘the moral leadership of the world must take up this issue.’ The beards nodded vigorously. They recalled no doubt the help the ‘moral leadership’ had given in Kabul and Kosovo. The Congressman paused; he didn’t want to mislead these people: what was on offer was not a ‘humanitarian war’ but an informal Camp David. ‘It needn’t even be the United States,’ he continued. ‘It could be a great man. It could be Nelson Mandela … or Bill Clinton.’

The beards were unimpressed. One of the few beardless men in the audience rose to his feet and addressed the Congressman: ‘Please answer honestly to our worries,’ he said. ‘In Afghanistan we helped you defeat the Red Army. You needed us then and we were very much loyal to you. Now you have abandoned us for India. Mr Clinton supports India, not human rights in Kashmir. Is this a good way to treat very old friends?’

The Congressman made sympathetic noises, even promising to tick Clinton off for not being ‘more vigorous on human rights in Kashmir’. He needn’t have bothered. A beard rose to ask why the US Government had betrayed them. The repetition irritated the Congressman. He took the offensive, complaining about this being an all-male meeting. Why were these men’s wives and daughters not present? The bearded faces remained impassive. As I went up the stairs the Congressman had changed tack again, and was speaking about the wondrous beauty of the valley of Kashmir.

‘The buildings of Kashmir are all of wood,’ the Mughal Emperor Jehangir wrote in his memoirs in March 1622. ‘They make them two, three and four-storeyed, and covering the roofs with earth, they plant bulbs of the black tulip, which blooms year after year with the arrival of spring and is exceedingly beautiful. This custom is peculiar to the people of Kashmir. This year, in the little garden of the palace and on the roof of the largest mosque, the tulips blossomed luxuriantly … The flowers that are seen in the territories of Kashmir are beyond all calculation.’ Surveying the lakes and waterfalls, roses, irises and jasmine, he described the valley as ‘a page that the painter of destiny had drawn with the pencil of creation’.

The first Muslim invasion of Kashmir took place in the eighth century and was defeated by the Himalayas. The soldiers of the Prophet found it impossible to move beyond the mountains’ southern slopes. Victory came unexpectedly five centuries later, as a result of a palace coup. Rinchana, the Buddhist chief from neighbouring Ladakh who carried out the coup, had sought refuge in Kashmir and embraced Islam under the guidance of a sufi with the pleasing name of Bulbul (‘nightingale’) Shah. Rinchana’s conversion would have been neither here nor there had it not been for the Turkish mercenaries who made up the ruler’s elite guard and were only too pleased to switch their allegiance to a co-religionist. But they swore to obey only the new ruler, not his descendants, so when Rinchana died, the leader of the mercenaries, Shah Mir, took control and founded the first Muslim dynasty to rule Kashmir. It lasted for seven hundred years.

The population, however, was not easily swayed and despite a policy of forced conversions it wasn’t until the end of the reign of Zain-al-Abidin in the late 15th century that a majority of Kashmiris embraced Islam. In fact, Zain-al-Abidin, an inspired ruler, ended the forced conversion of Hindus and decreed that those who had been converted in this fashion be allowed to return to their own faith. He even provided Hindus with subsidies enabling them to rebuild the temples his father had destroyed. The different ethnic and religious groups still weren’t allowed to intermarry but they learned to live side by side amicably enough. Zain-al-Abidin organised visits to Iran and Central Asia so that his subjects could learn bookbinding and woodcarving and how to make carpets and shawls, thereby laying the foundations for the shawl-making for which Kashmir is famous. By the end of his reign a large majority of the population had converted voluntarily to Islam and the ratio of Muslims to non-Muslims – 85 to 15 – has remained fairly constant ever since.

The dynasty went into a decline after Zain-al-Abidin’s death. Disputes over the succession, unfit rulers and endless intrigues among the nobility paved the way for new invasions. In the end the Mughal conquest in the late 16th century probably came as a relief to most people. The landlords were replaced by Mughal civil servants who administered the country rather more efficiently, reorganising its trade, its shawl-making and its agriculture. On the other hand, deprived of local patronage, Kashmir’s poets, painters and scribes left the valley in search of employment at the Mughal Courts in Delhi and Lahore, taking the country’s cultural life with them.

What made the disappearance of Kashmiri culture particularly harsh was the fact that the conquest itself coincided with a sudden flowering of the Kashmiri Court. Zoonie, the wife of Sultan Yusuf Shah, was a peasant from the village of Tsandahar who had been taken up by a Sufi mystic enchanted with her voice. Under his guidance, she learned Persian and began to write her own songs. One day, passing with his entourage and hearing her voice in the fields, Yusuf Shah, too, was captivated. He took her to Court and prevailed on her to marry him. And that is how Zoonie entered the palace as Queen and took the name of Habba Khatun (‘loved woman’). She wrote:

I thought I was indulging in play, and lost myself.

O for the day that is dying!

At home I was secluded, unknown,

When I left home, my fame spread far and wide,

The pious laid all their merit at my feet.

O for the day that is dying!

My beauty was like a warehouse filled with rare merchandise,

Which drew men from all the four quarters;

Now my richness is gone, I have no worth:

O for the day that is dying!

My father’s people were of high standing,

I became known as Habba Khatun:

O for the day that is dying.

Habba Khatun gave the Kashmiri language a literary form and encouraged a synthesis of Persian and Indian musical styles. She gave women the freedom to decorate themselves as they wished and revived the old Circassian tradition of tattooing the face and hands with special dyes and powders. The clerics were furious. They saw in her the work of Iblis, or Satan, in league with the blaspheming, licentious Sufis. While Yusuf Shah remained on the throne, however, Habba Khatun was untouchable. She mocked the pretensions of the clergy, defended the mystic strain within Islam and compared herself to a flower that flourishes in fertile soil and cannot be uprooted.

Habba Khatun was Queen when, in 1583, the Mughal Emperor, Akbar, despatched his favourite general to annex the Kingdom of Kashmir. There was no fighting: Yusuf Shah rode out to the Mughal camp and capitulated without a struggle, demanding only the right to retain the throne and strike coins in his image. Instead, he was arrested and sent into exile. The Kashmiri nobles, angered by Yusuf Shah’s betrayal, placed his son, Yakub Shah, on the throne, but he was a weak and intemperate young man who set the Sunni and the Shia clerics at one another’s throats and before long Akbar sent a large expeditionary force, which took Kashmir in the summer of 1588. In the autumn the Emperor came to see the valley’s famous colours for himself.

Habba Khatun’s situation changed dramatically after Akbar had her husband exiled. Unlike Sughanda and Dida, two powerful tenth-century queens who had ascended the throne as regents, Habba Khatun was driven out of the palace. At first she found refuge with the Sufis but after a time she began to move from village to village, giving voice in her songs to the melancholy of a suppressed people. There is no record of when or where she died – a grave, thought to be hers, was discovered in the middle of the last century – but women mourning the disappearance of young men killed by the Indian Army or ‘volunteered’ to fight in the jihad still sing her verses:

Who told him where I lived?

Why has he left me in such anguish?

I, hapless one, am filled with longing for him.

He glanced at me through my window,

He who is as lovely as my ear-rings;

He has made my heart restless:

I, hapless one, am filled with longing for him.

He glanced at me through the crevice in my roof,

Sang like a bird that I might look at him,

Then, soft-footed, vanished from my sight:

I, hapless one, am filled with longing for him.

He glanced at me while I was drawing water,

I withered like a red rose,

My soul and body were ablaze with love:

I, hapless one, am filled with longing for him.

He glanced at me in the waning moonlight of early dawn,

Stalked me like one obsessed.

Why did he stoop so low?

I, hapless one, am filled with longing for him!

Habba Khatun exemplified a gentle version of Islam, diluted with pre-Islamic practices and heavily influenced by Sufi mysticism. This tradition is still strong in the countryside and helps to explain Kashmiri indifference to the more militant forms of religion.

The Mughal Emperors were drawn to their new domain. Akbar’s son, Jehangir, who had described Kashmir as ‘a page that the painter of destiny had drawn with the pencil of creation’, lost his fear of death there, since paradise could only transcend the beauties of Kashmir. While his wife and brother-in-law kept their eye on the administration of the Empire, he reflected on his luck at having escaped the plains of the Punjab and spent his time planning gardens around natural springs so that the reflection of the rising and setting sun could be seen in the water as it cascaded down specially constructed channels. ‘If on earth there be a paradise of bliss, it is this, it is this, it is this,’ he wrote, citing a well-known Persian couplet.

By the 18th century, the Mughal Empire had begun its own slow decline and the Kashmiri nobles invited Ahmed Shah Durrani, the brutal ruler of Afghanistan, to liberate their country. Durrani obliged in 1752, doubling taxes and persecuting the embattled Shia minority with a fanatical vigour that shocked the nobles. Fifty years of Afghan rule were punctuated by regular clashes between Sunni and Shia Muslims.

Worse lay ahead, however. In 1819 the soldiers of Ranjit Singh, the charismatic leader of the Sikhs, already triumphant in northern India, took Srinagar. There was no resistance worth the name. Kashmiri historians regard the 27 years of Sikh rule that followed as the worst calamity ever to befall their country. The principal mosque in Srinagar was closed, others were made the property of the state, cow-slaughter was prohibited and, once again, the tax burden became insufferable – unlike the Mughals, Ranjit Singh taxed the poor. Mass impoverishment led to mass emigration. Kashmiris fled to the cities of the Punjab: Amritsar, Lahore and Rawalpindi became the new centres of Kashmiri life and culture. (One of the many positive effects of this influx was that Kashmiri cooks much improved the local food.)

Sikh rule didn’t last long: new conquerors were on the way. Possibly the most remarkable enterprise in the history of mercantile capitalism had launched itself on the Indian subcontinent. Granted semi-sovereign powers – i.e. the right to maintain armies – by the British and Dutch states, the East India Company expanded rapidly from its Calcutta base and, after the Battle of Plassey in 1757, took the whole of Bengal. Within a few years the Mughal Emperor at the Fort in Delhi had become a pensioner of the Company, whose forces continued to move west, determined now to take the Punjab from the Sikhs. The first Anglo-Sikh war in 1846 resulted in a victory for the Company, which acquired Kashmir as part of the Treaty of Amritsar, but, aware of the chaos there, hurriedly sold it for 75 lakh rupees (10 lakhs = 1 million) to the Dogra ruler of neighbouring Jammu, who pushed through yet more taxes. When, after the 1857 uprising, the East India Company was replaced by direct rule from London, real power in Kashmir, and other princely states, devolved to a British Resident, usually a fresh face from Haileybury College, serving an apprenticeship in the backwaters of the Empire.

Kashmir suffered badly under its Dogra rulers. The corvée was reintroduced after the collapse of the Mughal state and the peasants were reduced to the condition of serfs. A story told by Kashmiri intellectuals in the 1920s to highlight the plight of the peasants revolved round the Maharaja’s purchase of a Cadillac. When His Highness drove the car to Pehalgam, admiring peasants surrounded it and strewed fresh grass in front of it. The Maharaja acknowledged their presence by letting them touch the car. A few peasants began to cry. ‘Why are you crying?’ asked their ruler. ‘We are upset,’ one of them replied, ‘because your new animal refuses to eat grass.’

When it finally reached the valley, the 20th century brought new values: freedom from foreign rule, passive resistance, the right to form trade unions, even socialism. Young Kashmiris educated in Lahore and Delhi were returning home determined to wrench their country from the stranglehold of the Dogra Maharaja and his colonial patrons. When the Muslim poet and philosopher Iqbal, himself of Kashmiri origin, visited Srinagar in 1921, he left behind a subversive couplet which spread around the country:

In the bitter chill of winter shivers his naked body

Whose skill wraps the rich in royal shawls.

Kashmiri workers went on strike for the first time in the spring of 1924. Five thousand workers in the state-owned silk factory demanded a pay rise and the dismissal of a clerk who’d been running a protection racket. The management agreed to a small increase, but arrested the leaders of the protest. The workers then came out on strike. With the backing of the British Resident, the opium-sodden Maharaja Pratap Singh sent in troops. Workers on the picket-line were badly beaten, suspected ringleaders were sacked on the spot and the principal organiser of the action was imprisoned, then tortured to death.

Some months later, a group of ultra-conservative Muslim notables in Srinagar sent a memorandum to the British Viceroy, Lord Reading, protesting the brutality and repression:

Military was sent for and most inhuman treatment was meted out to the poor, helpless, unarmed, peace-loving labourers who were assaulted with spears, lances and other implements of warfare … The Mussulmans of Kashmir are in a miserable plight today. Their education is woefully neglected. Though forming 96 per cent of the population, the percentage of literacy amongst them is only 0.8 per cent … So far we have patiently borne the state’s indifference towards our grievances and our claims and its high-handedness towards our rights, but patience has its limit and resignation its end.

The Viceroy forwarded the petition to the Maharaja, who was enraged. He wanted the ‘sedition-mongers’ shot, but the Resident wouldn’t have it. As a sop he ordered the immediate deportation of the organiser of the petition, Saaduddin Shawl. Nothing changed even when, a few years later, the Maharaja died and was replaced by his nephew, Hari Singh. Albion Bannerji, the new British-approved Chief Minister of Kashmir, found the situation intolerable. Frustrated by his inability to achieve even trivial reforms, he resigned. ‘The large Muslim population,’ he said, ‘is absolutely illiterate, labouring under poverty and very low economic conditions of living in the villages and practically governed like dumb driven cattle.’

In April 1931, the police entered the mosque in Jammu and stopped the Friday khutba which follows the prayers. The police chief claimed that references in the Koran to Moses and Pharaoh quoted by the preacher were tantamount to sedition. It was an exceptionally stupid thing to do and, inevitably, it triggered a new wave of protests. In June the largest political rally ever seen in Srinigar elected 11 representatives by popular acclamation to lead the struggle against native and colonial repression. Among them was Sheikh Abdullah, the son of a shawl-trader, who would dominate the life of Kashmir for the next half-century.

One of the less well-known speakers at the rally, Abdul Qadir, a butler who worked for a European household, was arrested for having described the Dogra rulers as ‘a dynasty of blood-suckers’ who had ‘drained the energies and resources of all our people’. On the first day of Qadir’s trial, thousands of demonstrators gathered outside the prison and demanded the right to attend the proceedings. The police opened fire, killing 21 of them. Sheikh Abdullah and other political leaders were arrested the following day. This was the founding moment of Kashmiri nationalism.

At the same time, on the French Riviera, Tara Devi, the fourth wife of the dissolute and infertile Maharaja Hari Singh – he had shunted aside the first three for failing to produce any children – gave birth to a boy, Karan Singh. In the Srinagar bazaar every second person claimed to be the father of the heir-apparent. Five days of lavish entertainment and feasting marked the infant heir’s arrival in Srinagar. A few weeks later, public agitation broke out, punctuated by lampoons concerning the Maharaja’s lack of sexual prowess, among other things. The authorities sanctioned the use of public flogging, but it was too late. Kashmir could no longer be quarantined from a subcontinent eager for independence.

The Viceroy instructed the Maharaja to release the imprisoned nationalist leaders, who were carried through the streets of Srinagar on the shoulders of triumphant crowds. The infant Karan Singh had been produced in vain; he would never inherit his father’s dominion. Many years later he wrote of his father:

He was a bad loser. Any small setback in shooting or fishing, polo or racing, would throw him in a dark mood which lasted for days. And this would inevitably lead to what became known as a muqaddama, a long inquiry into the alleged inefficiency or misbehaviour of some hapless young member of staff or a servant … Here was authority without generosity; power without compassion.

On their release from jail, Sheikh Abdullah and his colleagues set about establishing a political organisation capable of uniting Muslims and non-Muslims. The All Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference was founded in Srinagar in October 1932 and Abdullah was elected its President. Non-Muslims in Kashmir were mainly Hindus, dominated by the Pandits, upper-caste Brahmins who looked down on Muslims, Sikhs and low-caste Hindus alike, but looked up to their colonial masters, as they had to the Mughals. The British, characteristically, used the Pandits to run the administration, making it easy for Muslims to see the two enemies as one. Abdullah, though a Koranic scholar, was resolutely secular in his politics. The Hindus may have been a tiny minority of the population, but he knew it would be fatal for Kashmiri interests if the Brahmins were ignored or persecuted. The confessional Muslims led by Mirwaiz Yusuf Shah broke away – the split was inevitable – accusing Abdullah of being soft on Hindus as well as those Muslims regarded by the orthodox as heretics. From the All India Kashmir Committee in Lahore came an angry poster addressed by the poet Iqbal to the ‘dumb Muslims of Kashmir’.

No longer constrained by the orthodox faction in his own ranks, Sheikh Abdullah drew closer to the social-revolutionary nationalism advocated by Nehru. He wasn’t the only Muslim leader to do so: Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan in the North-West Frontier Province, Mian Iftikharuddin in the Punjab and Maulana Azad in the United Provinces all decided to work with the Indian National Congress rather than the Muslim League, but it was not enough to tempt the majority of educated urban Muslims away from the Muslim League.

The Muslims had arrived in India as conquerors. They saw their religion as infinitely superior to that of the idol-worshipping Hindus and Buddhists. The bulk of Indian Muslims were nonetheless converts: some forced and others voluntary, seeking escape, in Kashmir and Bengal especially, from the rigours of the caste system. Thus, despite itself, Islam in India, as in coastal Africa, China and the Indonesian archipelago, was affected by local religious practices. Muslim saints were worshipped like Hindu gods. Holy men and ascetics were incorporated into Indian Islam. The Prophet Mohammed came to be regarded as a divinity. Buddhism had been especially strong in Kashmir, and the Buddhist worship of relics, too, was transferred to Islam, so that Kashmir is the home today for one of the holiest Muslim relics: a strand of hair supposedly belonging to Mohammed. The Koran expressly disavows necromancy, magic and omens and yet these superstitions remain a strong part of subcontinental Islam. Many Muslim political leaders still have favourite astrologers and soothsayers.

Muslim nationalism in India was the product of defeat. Until the collapse of the Mughal Empire at the hands of the British, Muslims had dominated the ruling class for over five hundred years. With the disappearance of the Mughal Court in Delhi and the culture it supported, they were now merely a large religious minority considered by Hindus as lower than the lowest caste. There was an abrupt retreat from the Persian-Hindu cultural synthesis they had created, orphaning the scribes, poets, traders and artisans who had flourished around the old Muslim courts. The poet Akbar Allahabadi (1846-1921) became the voice of India’s dispossessed Muslims, speaking for a community in decline:

The Englishman is happy, he owns the aeroplane,

The Hindu’s gratified, he controls all the trade,

’Tis we who are empty drums, subsisting on God’s grace,

A pile of biscuit crumbs and frothy lemonade.

The angry and embittered leaders of the Muslim community asked believers to wage a jihad against the infidel and to boycott everything he represented. The chief result was a near-terminal decline in Muslim education and intellectual life. In the 1870s, Syed Ahmed Khan, pleading for compromise, warned Muslims that their self-imposed isolation would have terrible economic consequences. In the hope of encouraging them to abandon the religious schools where they were taught to learn the Koran by rote in a language they couldn’t understand, he established the Muslim Anglo-Oriental College in Aligarh in 1875, which became the pre-eminent Muslim university in the country. Men and women from all over northern India were sent to be educated in English as well as Urdu.

It was here, at the end of the 1920s, that Sheikh Abdullah had enrolled as a student. The college authorities encouraged Muslims to stay away from politics, but by the time Sheikh Abdullah arrived in Aligarh, students were divided into liberal and conservative camps and it was difficult to avoid debates on religion, nationalism and Communism. Even the most dull-witted among them – usually those from feudal families – got involved. Most of the nationalist Muslims at Aligarh University aligned themselves with the Indian National Congress rather than the Muslim League, set up by the Aga Khan on behalf of the Viceroy.

To demonstrate his commitment to secular politics, Sheikh Abdullah invited Nehru to Kashmir. Nehru, whose forebears were Kashmiri Pandits, brought Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the ‘Frontier Gandhi’, with him. The three leaders spoke at consciousness-raising meetings and addressed groups of workers, intellectuals, peasants and women. What the visitors enjoyed most, however, was loitering in the old Mughal gardens. Like everyone else, Nehru had a go at describing the valley:

Like some supremely beautiful woman, whose beauty is almost impersonal and above human desire, such was Kashmir in all its feminine beauty of river and valley and lake and graceful trees. And then another aspect of this magic beauty would come into view, a masculine one, of hard mountains and precipices, and snow-capped peaks and glaciers, and cruel and fierce torrents rushing to the valleys below. It had a hundred faces and innumerable aspects, ever-changing, sometimes smiling, sometimes sad and full of sorrow … I watched this spectacle and sometimes the sheer loveliness of it was overpowering and I felt faint … It seemed to me dreamlike and unreal, like the hopes and desires that fill us and so seldom find fulfilment. It was like the face of the beloved that one sees in a dream and that fades away on wakening.

Sheikh Abdullah promised liberation from Dogra rule and pledged land reform; Nehru preached the virtues of unremitting struggle against the Empire and insisted that social reform could come only after the departure of the British; Ghaffar Khan spoke of the need for mass struggle and urged Kashmiris to throw fear to the wind: ‘You who live in the valleys must learn to scale the highest peaks.’

Nehru knew that the main reason they had been showered with affection was that Abdullah had been with them. There was now a strong political bond between the two men, though they weren’t at all similar. Abdullah was a Muslim from a humble background whose outlook remained provincial and whose political views arose from a hatred of suffering and of the social injustice he perceived to be its cause. Nehru, a product of Harrow and Cambridge, was a lofty figure, conscious of his own intellectual superiority, rarely afflicted by fear or envy, and always intolerant of fools. He was a left-wing internationalist and a staunch anti-Fascist. Yet, the ties established between the pair proved vital for Kashmir when separatism took over the subcontinent in 1947.

In a hangover from Mughal days and to make up for their lack of real power, the Muslims of India had developed an irritating habit of elevating their leaders with fancy titles. In this scheme Sheikh Abdullah became Sher-i-Kashmir, the Lion of Kashmir, and his wife Akbar Jehan Madri-i-Meharban, the Kind Mother. The Lion depended on the Kind Mother to impress famous visitors, to receive them during his frequent absences in prison, and to give him sound political advice. Akbar Jehan was the daughter of Harry Nedous, an Austro-Swiss hotelier, and Mir Jan, a Kashmiri milkmaid. The Nedous family had arrived in India at the turn of the last century and invested their savings in the majestic Nedous Hotel in Lahore – later there were hotels in Srinagar and Poona. Harry Nedous was the businessman; his brothers, Willy and Wally, willied and wallied around; his sister, Enid, took charge of the catering and her pâtisserie at their Lahore hotel was considered ‘as good as anything in Europe’.

Harry Nedous first caught sight of Mir Jan when she came to deliver the milk at his holiday lodge in Gulmarg. He was immediately smitten, but she was suspicious. ‘I might be poor,’ she told him later that week, ‘but I am not for sale.’ Harry pleaded that he was serious, that he loved her, that he wanted to marry her. ‘In that case,’ she retorted wrathfully, ‘you must convert to Islam. I cannot marry an unbeliever.’ To her amazement, he did so, and in time they had 12 children (only five of whom survived). Brought up as a devout Muslim, their daughter Akbar Jehan was a boarder at the Convent of Jesus and Mary in the hill resort of Murree. Non-Christian parents often packed their daughters off to these convents because the education was quite good and the regime strict, though there is evidence to suggest they spent much of their time fantasising about Rudolph Valentino.

In 1928, when a 17-year-old Akbar Jehan had left school and was back in Lahore, a senior figure in British Military Intelligence checked in to the Nedous Hotel on the Upper Mall. Colonel T.E. Lawrence, complete with Valentino-style headgear, had just spent a gruelling few weeks in Afghanistan destabilising the radical, modernising and anti-British regime of King Amanullah. Disguised as ‘Karam Shah’, a visiting Arab cleric, he had organised a black propaganda campaign designed to stoke the religious fervour of the more reactionary tribes and thus provoke a civil war. His mission accomplished, he left for Lahore. Akbar Jehan must have met him at her father’s hotel. A flirtation began and got out of control. Her father insisted that they get married immediately; which they did. Three months later, in January 1929, Amanullah was toppled and replaced by a pro-British ruler. On 12 January, Kipling’s old newspaper in Lahore, the imperialist Civil and Military Gazette, published comparative profiles of Lawrence and ‘Karam Shah’ to reinforce the impression that they were two different people. Several weeks later, the Calcutta newspaper Liberty reported that ‘Karam Shah’ was indeed the ‘British spy Lawrence’ and gave a detailed account of his activities in Waziristan on the Afghan frontier. Lawrence was becoming a liability and the authorities told him to return to Britain. ‘Karam Shah’ was never seen again. Nedous insisted on a divorce for his daughter and again Lawrence obliged. Four years later, Sheikh Abdullah and Akbar Jehan were married in Srinagar. The fact of her previous marriage and divorce was never a secret: only the real name of her first husband was hidden. She now threw herself into the struggle for a new Kashmir. She raised money to build schools for poor children and encouraged adult education in a state where the bulk of the population was illiterate. She also, crucially, gave support and advice to her husband, alerting him, for example, to the dangers of succumbing to Nehru’s charm and thus compromising his own standing in Kashmir.

Few politicians in the 1930s believed that the subcontinent would ever be divided along religious lines. Even the most ardent Muslim separatists were prepared to accept a federation based on the principle of regional autonomy. In the 1937 elections the Congress Party swept most of the country, including the Muslim-majority North-West Frontier Province, where Ghaffar Khan’s popularity was at its peak. The Muslim-majority provinces of the Punjab and Bengal remained loyal to the Raj and voted for secular parties controlled by the landed gentry. Contrary to Pakistani mythology, separatism wasn’t at this stage an aim so much as a bargaining tool to ensure that Muslims received a fair share of the post-colonial spoils.

The Second World War changed everything. India was included in Britain’s declaration of war against Germany and the Congress Party was livid at His Majesty’s Government’s failure to consult them. Nehru would probably have argued in favour of participating in the anti-Fascist struggle provided the British agreed to leave India once it was all over, and London would probably have regarded such a request as impertinent. As it was, the Congress Governments of each province resigned. Gandhi, who, despite his pacifism, had acted as an efficient recruiting-sergeant for the British during the First World War, was less sure what to do this time. A hardline ultra-nationalist current within the Congress led by the charismatic Bengali Subhas Chandra Bose argued for an alliance with Britain’s enemies, particularly Japan. This was unacceptable to Nehru and Gandhi. But when Singapore fell in 1942, Gandhi, like most observers, was sure that the Japanese were about to take India by way of Bengal and argued that the Congress had to oppose the British Empire, whatever the cost, in order to be in a position to strike a deal with the Japanese. The wartime coalition in London sent Stafford Cripps to woo the Congress back into line. He offered its leaders a ‘blank cheque’ after the war. ‘What is the point of a blank cheque from a bank that is already failing?’ Gandhi replied. In August 1942 the Congress leaders authorised the launch of the Quit India movement. A tidal wave of civil disobedience swept the country. The entire Congress leadership, including Gandhi and Nehru, was arrested, as were thousands of organisers and workers. The Muslim League backed the war effort and prospered. Partition was the ultimate prize.

When Nehru and Ghaffar Khan revisited Srinigar as Abdullah’s guests in the summer of 1945 it was evident that divisions between the different nationalists were acute. The Lion of Kashmir had laid on a Mughal-style welcome. The guests were taken downriver on lavishly decorated shikaras (gondolas). Barred from gathering on the four bridges along the route, Abdullah’s local Muslim opponents stood on the embankment, dressed in phirens, long tunics which almost touched the ground. In the summer months it was customary not to wear underclothes. As the boats approached, the male protesters, who had not been allowed to carry banners, faced the guests and lifted their phirens; the women turned their backs and bared their buttocks. Muslims had never protested in this way before, and have not done so since. Ghaffar Khan roared with laughter, but Nehru was not amused. Later that day Ghaffar Khan referred to the episode at a rally and told the audience how impressed he had been by the wares on display. Nehru, asked at a dinner the next day how he compared the regions he had visited most recently, replied: ‘Punjabis are crude, Bengalis are hysterical and the Kashmiris are simply vulgar.’

The confessional movement was gaining strength, however. Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the founding father of Pakistan, had left the Congress in the 1930s partly because he was uneasy about Gandhi’s use of Hindu religious imagery. He had then joined the Muslim League in a partially successful attempt to wrest it from the collaborationist landlords of the United Provinces. Jinnah had half-hoped, half-believed that Pakistan would be a smaller version of India, but one in which Muslims would dominate, with Hindus and Sikhs still living there and forming a loyal minority. Had a confederal solution been adopted this might have been possible, but once the decision to split had been accepted as irrevocable by the departing British, it was out of the question. Bengal and the Punjab were mixed provinces and so they, too, would have to be divided. As they were.

Crimes were committed by all sides. Those who were reluctant to abandon their villages were driven out or massacred. Trains carrying refugee families were attacked by armed gangs and became moving coffins. There are no agreed figures, but according to the lowest estimates, the slicing of the subcontinent cost nearly a million lives. No official monument marks the casualties of Partition, there is no official record of those who perished. Amrita Pritam, an 18-year-old Sikh, born and brought up in Lahore but now forced to become a refugee, left behind a lament in which she evoked the medieval Sufi poet and free-thinker, Waris Shah, whose love-epic ‘Heer-Ranjha’ was (and is) sung in almost every Punjabi village on both sides of the divide:

I call Waris Shah today:

‘Speak up from your grave,

From your Book of Love unfurl

A new and different page.

One daughter of the Punjab did scream

You covered our walls with your laments.’

Millions of daughters weep today

And call out to Waris Shah:

‘Arise you chronicler of our inner pain

And look now at your Punjab;

The forests are littered with corpses

And blood flows down the Chenab.’

Kashmir is the unfinished business of Partition. The agreement to divide the subcontinent had entailed referendums and elections in the Muslim majority segments of British India. In the North-West Frontier Province, which was 90 per cent Muslim, the Muslim League had defeated the anti-Partition forces led by Ghaffar Khan. It did so by intimidation, chicanery and selective violence. The Muslim League never won a free election there again and Ghaffar Khan spent much of the rest of his life – he died in the 1980s – in a Pakistani prison accused of treason. His defeat seemed to prove that secular Muslim leaders, despite their popularity, were powerless against the confessional tide. Would Sheikh Abdullah be able to preserve a united Kashmir?

In constitutional terms, Kashmir was a ‘princely state’, which meant that the Maharaja had the legal right to choose whether to accede to India or to Pakistan. In cases where the ruler did not share the faith of a large majority of his population it was assumed he would nevertheless go along with the wishes of the people. In Hyderabad and Junagadh – Hindu majority, Muslim royals – the rulers wobbled, but finally chose India. Jinnah began to woo the Maharaja of Kashmir in the hope that he would decide in favour of Pakistan. This enraged Sheikh Abdullah. Hari Singh vacillated.

Kashmir’s accession was still unresolved when midnight struck on 14 August 1947 and the Union Jack was lowered for the last time. Independence. There were now two armies in the subcontinent, each commanded by a British officer and with a very large proportion of British officers in the senior ranks. Lord Mountbatten, the Governor-General of India, and Field Marshal Auchinleck, the Joint Commander-in-Chief of both armies, made it lear to Jinnah that the use of force in Kashmir would not be tolerated. If it was attempted, Britain would withdraw every British officer from the Pakistan Army. Pakistan backed down. The League’s traditional toadying to the British played a part in this decision, but there were other factors: Britain exercised a great deal of economic leverage; Mountbatten’s authority was resented but could not be ignored; Pakistan’s civil servants hadn’t yet much self-confidence. And, unknown to his people, Jinnah was dying of tuberculosis. Besides, Pakistan’s first Prime Minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, an upper-class refugee from India, was not in any sense a rebel. He had worked too closely with the departing colonial power to want to thwart it. He had no feel for the politics of the regions that now comprised Pakistan and he didn’t get on with the Muslim landlords who dominated the League in the Punjab. They wanted to run the country and would soon have him killed, but not just yet.

Meanwhile, something had to be done about Kashmir. There was unrest in the Army and even secular politicians felt that Kashmir, as a Muslim state, should form part of Pakistan. The Maharaja had begun to negotiate secretly with India and a desperate Jinnah decided to authorise a military operation in defiance of the British High Command. Pakistan would advance into Kashmir and seize Srinagar. Jinnah nominated a younger colleague from the Punjab, Sardar Shaukat Hyat Khan, to take charge of the operation.

Shaukat had served as a captain during the war and spent several months in an Italian POW camp. On his return he had resigned his commission and joined the Muslim League. He was one of its more popular leaders in the Punjab, devoted to Jinnah, extremely hostile to Liaquat, whom he regarded as an arriviste, and keen to earn the title of ‘Lion of the Punjab’ that was occasionally chanted in his honour at public meetings. An effete and vainglorious figure, easily swayed by flattery, Shaukat was a chocolate-cream soldier. It was the unexpected death of his father, the elected Prime Minister of the old Punjab, that had brought him to prominence. He was not one of those people who rise above their own shortcomings in a crisis. I knew him well: he was my uncle. To his credit, however, he argued against the use of irregulars and wanted the operation to be restricted to retired or serving military personnel. He was overruled by the Prime Minister, who insisted that his loud-mouthed protégé, Khurshid Anwar, take part in the operation. Anwar, against all military advice, enlisted Pathan tribesman in the cause of jihad. Two extremely able brigadiers, Akbar Khan and Sher Khan from the 6/13th Frontier Force Regiment (‘Piffers’ to old India hands), were selected to lead the assault.

The invasion was fixed for 9 September 1947, but it had to be delayed for two weeks: Khurshid Anwar had chosen the same day to get married and wanted to go on a brief honeymoon. In the meantime, thanks to Anwar’s lack of discretion, a senior Pakistani officer, Brigadier Iftikhar, heard what was going on and passed the news to General Messervy, the C-in-C of the Pakistan Army. He immediately informed Auchinleck, who passed the information to Mountbatten, who passed it to the new Indian Government. Using the planned invasion as a pretext, the Congress sent Nehru’s deputy, Sardar Patel, to pressure the Maharaja into acceding to India, while Mountbatten ordered Indian Army units to prepare for an emergency airlift to Srinagar.

Back in Rawalpindi, Anwar had returned from his honeymoon and the invasion began. The key objective was to take Srinagar, occupy the airport and secure it against the Indians. Within a week the Maharaja’s army had collapsed. Hari Singh fled to his palace in Jammu. The 11th Sikh Regiment of the Indian Army had by now reached Srinagar, but was desperately waiting for reinforcements and didn’t enter the town. The Pathan tribesman under Khurshid Anwar’s command halted after reaching Baramulla, only an hour’s bus ride from Srinagar, and refused to go any further. Here they embarked on a three-day binge, looting houses, assaulting Muslims and Hindus alike, raping men and women and stealing money from the Kashmir Treasury. The local cinema was transformed into a rape centre; a group of Pathans invaded St Joseph’s Convent, where they raped and killed four nuns, including the Mother Superior, and shot dead a European couple sheltering there. News of the atrocities spread, turning large numbers of Kashmiris against their would-be liberators. When they finally reached Srinagar, the Pathans were so intent on pillaging the shops and bazaars that they overlooked the airport, already occupied by the Sikhs.

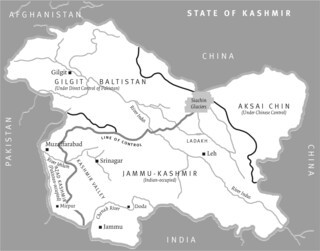

The Maharaja meanwhile signed the accession papers in favour of India and demanded help to repel the invasion. India airlifted troops and began to drive the Pakistanis back. Sporadic fighting continued until India appealed to the UN Security Council, which organised a ceasefire and a Line of Control (LOC) demarcating Indian and Pakistan-held territory.* Kashmir, too, was now partitioned. The leaders of the Kashmir Muslim Conference shifted to Muzaffarabad in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, leaving Sheikh Abdullah in control of the valley itself.

If Abdullah, too, had favoured Pakistan, there wouldn’t have been much that the Indian troops could have done about it. But he regarded the Muslim League as a reactionary organisation and rightly feared that if Kashmir became part of Pakistan, the Punjabi landlords who dominated the Muslim League would stand in the way of any social or political reforms. He decided to back the Indian military presence, provided the Kashmiris were allowed to determine their own future. At a mass rally in Srinagar, Nehru, with Abdullah at his side, publicly promised as much. In November 1947, Abdullah was appointed Prime Minister of an Emergency Administration. When the Maharaja expressed nervousness about this, Nehru wrote to him, insisting that there was no alternative: ‘The only person who can deliver the goods in Kashmir is Abdullah. I have a high opinion of his integrity and his general balance of mind. He may make any number of mistakes in minor matters, but I think he is likely to be right in regard to major decisions. No satisfactory way out can be found in Kashmir except through him.’

In 1944 the National Conference had approved a constitution for an independent Kashmir, which began:

We the people of Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh and the Frontier regions, including Poonch and Chenani districts, commonly known as Jammu and Kashmir State, in order to perfect our union in the fullest equality and self-determination, to raise ourselves and our children for ever from the abyss of oppression and poverty, degradation and superstition, from medieval darkness and ignorance, into the sunlit valleys of plenty, ruled by freedom, science and honest toil, in worthy participation of the historic resurgence of the peoples of the East, and the working masses of the world, and in determination to make this our country a dazzling gem on the snowy bosom of Asia, do propose and propound the following constitution of our state . . .

But the 1947-48 war had made independence impossible, and Article 370 of the Indian Constitution recognised only Kashmir’s ‘special status’. True, the Maharaja was replaced by his son, Karan Singh, who became the non-hereditary head of state, but it was a disappointed Abdullah who now sat down to play chess with the politicians from Delhi. He knew that most of them, apart from Gandhi and Nehru, would like to eat him alive. For the moment, though, they needed him. Since the split with the confessional element in the Jammu and Kashmir Conference, Abdullah had moved to the left. As the elected Chief Minister of Kashmir he pushed through a set of major reforms, the most important of which was the ‘land to the tiller’ legislation, which destroyed the power of the landlords, most of whom were Muslims. They were allowed to keep a maximum of 20 acres, provided they worked on the land themselves: 188,775 acres were transferred to 153,399 peasants, while the Government organised collective farming on 90,000 acres. A law was passed prohibiting the sale of land to non-Kashmiris, thus preserving the basic topography of the region. Dozens of new schools and four hospitals were built, and a university was founded in Srinagar with perhaps the most beautiful location of any campus in the world.

These reforms were regarded as Communist-inspired in the United States, where they were used to build support for America’s new ally, Pakistan. A classic example of US propaganda is Danger in Kashmir, written by Josef Korbel. Korbel had been a Czech UN representative in Kashmir before he defected to Washington. His book was published by Princeton in 1954, and in the second edition, in 1966, Korbel acknowledged the ‘substantial help’ of several scholars, including Mrs Madeleine Albright of the Russian Institute at Columbia University – his daughter.

In 1948 the National Conference had backed ‘provisional accession’ to India, on condition Kashmir was accepted as an autonomous republic with only defence, foreign affairs and communications conceded to the centre. A small but influential minority, made up of the Dogra nobility and the Kashmiri Pandits, fearful of losing their privileges, began to campaign against Kashmir’s special status. In India proper, they were backed by the ultra-right Jan Sangh (which in its current reincarnation as the Bharatiya Janata Party heads the coalition Government in New Delhi). The Jan Sangh provided funds and volunteers for agitation against the Kashmir Government. Abdullah, who had gone out of his way to integrate non-Muslims at every level of the Administration, was enraged. His position hardened. At a public meeting in the enemy stronghold of Jammu on 10 April 1952, he made it clear that he was not willing to surrender Kashmir’s partial sovereignty:

Many Kashmiris are apprehensive as to what will happen to them and their position if, for instance, something happens to Pandit Nehru. We do not know. As realists, we Kashmiris have to provide for all eventualities . . . If there is a resurgence of communalism in India how are we to convince the Muslims of Kashmir that India does not intend to swallow up Kashmir?

Abdullah was mistaken only in his belief that Nehru would protect them. When the Indian Prime Minister visited Srinagar in May 1953 he spent a week trying to cajole his friend into accepting a permanent settlement on Delhi’s terms: if a secular democracy was to be preserved in India, Kashmir had to be part of it. Nehru pleaded. Abdullah wasn’t convinced: Muslims were a large minority in India even if Kashmiris weren’t included. He felt that Nehru shouldn’t be putting pressure on him but on politicians inside the Congress who were susceptible to the chauvinistic demands of the Jan Sangh.

Three months later, Nehru gave in to the chauvinists and authorised what was effectively a coup in Kashmir. Sheikh Abdullah was dismissed by Karan Singh and one of his lieutenants, Bakhshi Ghulam Mohammed, was sworn in as Chief Minister. Abdullah was accused of being in contact with Pakistani intelligence and arrested. Kashmir erupted. A general strike began which was to last for twenty days. There were several thousand arrests and Indian troops repeatedly opened fire on demonstrators. The National Conference claimed that more than a thousand people were killed: official statistics record 60 deaths. An underground War Council, organised by Akbar Jehan, orchestrated demonstrations by women in Srinagar, Baramulla and Sopore.

The unrest subsided after a month, but now Kashmiris were even more suspicious of India. The situation was no happier in Pakistani-controlled Kashmir, which had the additional disadvantage of being made up of the least attractive part of the old state, a barren moonscape. Appalling living conditions gave rise to large-scale economic migration. Today, more Kashmiris live in Birmingham and Bradford than in Mirpur or Muzaffarabad. An Islamist Kashmiri sits in the House of Lords as a new Labour peer; another Kashmiri is the Tory candidate for Bolton East.

Sheikh Abdullah, detained for four years without trial, was released without warning one cold morning in January 1958. Declining the offer of government transport, he hired a taxi and was driven to Srinagar. Within days he was drawing huge crowds at meetings all over the country, which he used to remind Nehru of the promise he had made in 1947. ‘Why did you go back on your word, Panditji?’ Abdullah would ask, and the crowds would echo the question. By spring, he had been arrested again. This time the Indian Government, using British colonial legislation, began to prepare a conspiracy case against him, his wife and several other nationalist leaders. Nehru vetoed Akbar Jehan’s inclusion: her popularity made it inadvisable. The conspiracy trial began in 1959 and lasted more than a year. In 1962 the special magistrate transferred the case to a higher court with the recommendation that the accused be tried under sections of the Indian penal code for which the punishment was either death or life imprisonment.

In December 1963, with the higher court still considering the conspiracy charges, the single hair of the Prophet’s head was stolen from the Hazrat Bal shrine in Srinagar. Its theft created uproar: an Action Committee was set up and the country was paralysed by a general strike and mass demonstrations. A distraught Nehru ordered that the strand of hair be found – and it was, within a week. But was it the real thing? The Action Committee called on religious leaders to inspect it. Faqir Mirak Shah, regarded as ‘the holiest of the holy men’, announced that it was genuine. The crisis abated. Nehru concluded that a lasting solution had to be found to the problem of Kashmir. He had the conspiracy case against Abdullah dropped, and the Lion of Kashmir was released after six years in prison. A million people lined the streets to mark his return: Nehru spoke of the necessity of ending hostilities between India and Pakistan.

Kashmir troubled Nehru’s conscience. He met Abdullah in Delhi and told him that he wanted the problem of Kashmir resolved in his lifetime. He suggested that Abdullah visit Pakistan and sound out its leader, General Ayub Khan. If Pakistan was ready to accept a solution proposed by Abdullah, then Nehru would, too. For a start, India was prepared to allow free movement of goods and people across the ceasefire line. Abdullah flew to Pakistan in an optimistic mood. After a series of conversations with Ayub Khan he felt progress was being made. On 27 May 1964, he reached Muzaffarabad, the capital of Pakistani-controlled Kashmir, and was cheered by a large crowd. He was addressing a press conference when a colleague rushed in to inform him that All India Radio had just announced Nehru’s death. Sheikh Abdullah broke down and wept. He cancelled all his engagements and, accompanied by Pakistan’s Foreign Minister, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, flew back to Delhi to attend his old friend’s funeral.

Fearing that there would be no peaceful solution without Nehru, Abdullah travelled around the world, trying to get international support, and was received in several capitals with the honours accorded a visiting head of state. His meeting with the Chinese Prime Minister Zhou En Lai (‘Chew and Lie’ in the ultra-patriotic sections of the Indian press) created a furore in India. And so, on his return, Abdullah was imprisoned again. This time he and his wife were sent to prisons far away from Kashmir. The response was the usual: strikes, demonstrations, arrests and a few deaths.

Encouraged by this, the military regime in Pakistan despatched several platoons of irregulars in September 1965, hoping to spark off an uprising. As usual, they had misjudged the situation. The unrest was not an expresion of pro-Pakistan sentiments. The Pakistan Army crossed the Line of Control, aiming to cut Kashmir off from the rest of India. The Military High Command was confident. On the eve of the invasion, the self-appointed Field Marshal Ayub Khan had boasted that they might even be able to take Amritsar – the Indian town closest to Lahore – as a bargaining chip. A senior officer present (another of my uncles) muttered loudly: ‘Give him a few more whiskies and we’ll take Delhi as well.’ The Indian Army, caught by surprise, suffered serious reverses. They responded dramatically by crossing the Pakistan border near Lahore. Had the war continued, the city would have fallen, but Ayub Khan appealed to Washington for support. Washington asked Moscow to bring pressure on India and a peace agreement was signed in Tashkent under the watchful eye of Alexei Kosygin.

The war had been Bhutto’s idea. Ayub Khan, publicly humiliated at home and abroad, sacked his Foreign Minister. Bhutto had always been the most awkward member of the Government and, embarrassed at having to serve under a general, he had ratcheted up his nationalist rhetoric. Government ministers, fearing trouble, tended to avoid the universities, but a few years before this, in 1962, Bhutto had decided to address a student meeting on Kashmir at the Punjab University in Lahore, at which I was present. He spoke eloquently enough, but we were more concerned with domestic politics. We began to talk to each other. He was offended. He stopped in mid-flow and glared at us aggressively. ‘What the hell do you want? I’ll answer your questions.’ I raised my hand. ‘We’re all in favour of a democratic referendum in Kashmir,’ I began, ‘but we would like one in Pakistan as well. Why should anybody take you seriously on democracy in Kashmir when it doesn’t exist here?’

He glared at me angrily, but wouldn’t be drawn, pointing out that he had only agreed to speak on Kashmir. At this point the meeting erupted, with everyone demanding a reply and chanting slogans. At one point Bhutto took off his jacket and challenged a heckler to a boxing match outside. This was greeted with jeers and the meeting came to an abrupt halt. That night Bhutto cursed us roundly as one drained whisky glass after another was hurled against the wall, an affectation he had picked up during an official trip to Moscow. Many months later he told me that the encounter had made him realise how powerful the students were.

A week after Bhutto’s dismissal in spring 1966 – by which time I was a student in the UK – I received a phone call from J.A. Rahim, Pakistan’s Ambassador to France. He needed to see me in Paris the next day. He would pay my return ticket and offered the bribe of a ‘sensational lunch’.

An Embassy chauffeur picked me up at Orly and drove me to the restaurant. His Excellency, a cultured Bengali in his late fifties, greeted me with a conspiratorial warmth, which was surprising since we had never met. Halfway through the hors-d’oeuvres he lowered his voice and asked: ‘Don’t you think the time has come to get rid of the Field Marshal?’ Concealing my surprise, not to mention fear, I asked him to elaborate. He raised his hand above the table, pointed two fingers at me and pulled an imaginary trigger. He wanted me to help organise Ayub Khan’s assassination. My instinctive reaction was to forget the main course and leave. How could this be anything other than a set-up? Rahim ordered another bottle of Château Latour, courtesy of the Pakistan Government. I pointed out the danger of removing an individual military leader while leaving the institution intact. In any case, I added, it would be difficult for me to organise the assassination from Oxford. He glared at me. ‘Drastic action is needed,’ he said, ‘and you’re just trying to avoid the issue. The Army is enfeebled after this wretched war. Everyone is fed up. Remove him and anything is possible. I’m surprised at you. I don’t expect you to do it yourself. One of your uncles is always boasting about the hereditary assassins in your villages who’ve acted for your family in the past.’

I tried to talk about Kashmir but Rahim wasn’t interested. ‘Kashmir,’ he said, ‘is irrelevant. It’s the dictatorship we’re after.’ A week later, Rahim resigned his ambassadorship. A few months after that he turned up in London with Bhutto and summoned me to the Dorchester. I had heard that Bhutto was depressed, but there was no trace of it that day. Conscious of the shortness of life, he was the sort of man who was determined that it should flash by with brilliance, romance and verve. He could also be silly, arrogant, childish and vindictive – defects which cost him his life.

At one point, when Rahim was out of the room, I began to describe our lunch in Paris, but Bhutto already knew about it. He laughed and insisted that Rahim had just been testing me. Then he whispered: ‘When you met Rahim in Paris did he introduce you to his new mistress?’ I shook my head regretfully. ‘I’m told she’s very pretty and very young. He’s hiding her from me. I was hoping you might have . . .’ Rahim came back with a bulky typescript. It was the manifesto of the Pakistan People’s Party, which he had drafted on Bhutto’s instructions.

‘Go into the next room, read it carefully and tell me what you think,’ Bhutto ordered. ‘I want you to become a founding member.’ I was halfway through it when the author walked in with an apologetic smile. ‘Bhutto wants to be alone. He’s booked a call to Geneva. Did you know he’s got a Japanese mistress there? Have you met her?’ I shook my head. ‘He’s hiding her from me,’ Rahim said. ‘I wonder why.’

I finished reading the manifesto. It was strong on anti-imperialist rhetoric, self-determination for Kashmir, land reform, nationalisation of industry, but far too soft on religion. I couldn’t associate myself with a party that wasn’t 100 per cent secular and Rahim smiled in agreement, but Bhutto was angry and denounced us both. Later that evening, during dinner, I asked why he had embroiled the country in an unwinnable war. The reply was breathtaking. ‘It was the only way to weaken the bloody dictatorship. The regime will crack wide open soon.’

Subsequent events appeared to vindicate Bhutto’s judgment. In 1968 a prolonged uprising of students and workers finally toppled it. The traditional parties on the Left had not grasped the importance of what was happening, but Bhutto put himself at the head of the revolt, promised that after the people’s victory, they would ‘dress the generals in skirts and parade them through the streets like performing monkeys’, and prospered politically.

When I met him in Karachi in August 1969, he was in ebullient mood. The stopgap dictator had promised a general election and he was sure his party would win. Once again he mocked me for refusing to join. ‘There are only two ways: mine or Che Guevara’s. Are you planning to start a guerrilla war in the mountains of Baluchistan?’

Bhutto scored an amazing triumph in the 1970 election, but only in West Pakistan. In what was then East Pakistan and is now Bangladesh the nationalist leader Sheikh Mujibur Rehman and his Awami League won virtually every seat. Since 60 per cent of the population lived in East Pakistan, Mujib gained an overall majority in the National Assembly and expected to become Prime Minister. The Punjabi elite refused to hand over power and instead arrested him. General Yahya (‘fuck-fuck’ in Lahori Punjabi) Khan attempted to crush the Bengalis, and Bhutto, desperate for power, supported him. It was his most shameful hour. A Bangladeshi Government-in-Exile was set up in neighbouring Calcutta. Millions of refugees poured into the Indian province of West Bengal and, finally, at the request of the Bengali leaders in exile, the Indian Army moved into East Pakistan to be greeted by the population as liberators. Pakistan surrendered and Bangladesh was born.

Bhutto came to power in a truncated Pakistan, but the old game was over: in 1972, at the Indian hill resort of Simla, he agreed to the status quo in Kashmir and in return got back the 90,000 soldiers who had been captured after the fall of Dhaka in what had been East Pakistan. In Kashmir every political group, with the exception of the confessional Jamaat-i-Islami, was shocked by the brutalities inflicted on fellow Muslims in Bengal. Had a referendum been held at this point, a majority would have opted to remain within the Indian Federation, but Delhi refused to take the risk. Pakistan’s reputation continued to sink when its third military dictator, a Washington implant called Zia-ul-Haq, executed Bhutto in 1979 after a rigged trial. A large rally in Srinagar turned into a prayer meeting for the dead leader.

Sheikh Abdullah (released from prison on grounds of ill-health in the mid-1970s) had made his peace with Delhi and was again appointed Chief Minister in 1977, courtesy of Mrs Gandhi, who forced Congress yes-men in the Kashmir Assembly, themselves elected by dubious means, to switch sides and vote for him. The change-over was calm: Kashmiris were pleased at Abdullah’s return, but mindful of the fact that Mrs Gandhi was calling the tune.

Abdullah seemed stale and tired, his time in prison had affected both his health and his politics. He now mimicked other subcontinental potentates by attempting to create a political dynasty. It’s said that Akbar Jehan insisted he do so and that he was too old and weak to resist. At a big rally in Srinagar he named his oldest son, Farooq Abdullah – an amiable doctor, fond of wine and fornication, but not very bright – as his successor.

As he lay dying in 1982, Sheikh Abdullah told an old friend of a dream that had haunted him for the past thirty years. ‘I am still a young man. I’m dressed as a bridegroom. I’m on horseback. My bridal party leaves our home with all the fanfare. We head in the direction of the bride’s house. But when I arrive she’s not there. She’s never there. Then I wake up.’ The missing bride, so it has alway seemed to me, was Nehru. Abdullah had never fully recovered from his betrayal.

In 1984 I asked Indira Gandhi about India’s loss of nerve over Kashmir. She didn’t offer any explanation for the failure to hold a referendum and agreed that 1979 might have been the time to take the risk, but, she reminded me with a smile, ‘I was not in power that year. If I had been Prime Minister,’ she added, ‘I would not have let them hang Bhutto next door.’

When I met Sheikh Abdullah’s son at a conclave of opposition parties in Calcutta, he was scathing about Delhi’s failures, but still convinced that a referendum would not go Pakistan’s way. ‘She’s getting too old,’ he said about Mrs Gandhi. ‘Look at me. Who am I? In Indian terms a nobody. A provincial politician. If she had left me alone there would have been no problems. Her Congressmen in Kashmir were bitter at having been defeated so they began to agitate, but for what? For power which the electorate had denied them. I met Mrs Gandhi a number of times to assure her that we were loyal, intended to remain so and wanted friendly relations with the centre. Her paranoia was such that she wanted one to be totally servile. That was impossible. So she gave the Kashmir Congress the green light to disrupt our Government’s functioning. It was she who made me a national leader. I would have been far happier left alone in our lovely Kashmir.’

When I passed this on to her, Mrs Gandhi snorted derisively. ‘Yes, yes, I know that’s what he says. He said similar things to me, but he acts differently. Tells too many lies. The boy is totally untrustworthy.’ Meanwhile her ‘sources’ had informed her that Pakistan was preparing a military invasion of Kashmir. Could this be so? I doubted it. General Zia-ul-Haq was brutal and vicious, but he wasn’t an idiot. He knew that to provoke India would be fatal. In addition, the Pakistan Army was busy fighting the Soviet Union in Afghanistan. To open a second front in Kashmir would be the height of irrationality.

‘I’m surprised at you,’ she said. ‘You of all people believe that generals are rational human beings?’

‘There is a difference between irrationality and suicide,’ I said.

She smiled, but didn’t reply. Then, to demonstrate the inadequacies of the military mind, she described how after Pakistan’s surrender in Bangladesh, her generals had wanted to continue the war against West Pakistan, to ‘finish off the enemy’. She overruled them and ordered a ceasefire. Her point was that in India the Army was firmly under civilian control, but in Pakistan it was a law unto itself.

Later that evening – I was staying in Delhi – I received a phone call from a civil servant. ‘I believe you had a very interesting discussion with the PM. We have an informal discussion club meeting tomorrow and would love you to come and talk to us.’ The members of the club were civil servants, intelligence operatives and journalists from both the US and Soviet lobbies. They tried to convince me that I was wrong, that the Pakistani generals were planning an attack. After two hours of argument and counter-argument I began to tire. ‘Listen,’ I said, ‘if you lot are preparing a pre-emptive strike against Zia or the nuclear reactor in Kahuta, that’s your decision. You might even win support in Sind and Baluchistan, but don’t expect the world to believe you acted in response to Pakistani aggression. It’s simply not credible at the moment.’ The meeting came to an end. Back in London I described these events to Bhutto’s daughter, Benazir. ‘Why did you deny that Zia was planning to invade Kashmir?’ she interrupted.

Four months later Mrs Gandhi was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards. A civil servant I met in Delhi the following year told me they had evidence linking the assassins with Sikh training camps in Pakistan set up with US assistance with a view to destabilising the Indian Government. He was sure the US had decided to eliminate Mrs Gandhi in order to prevent a strike against Pakistan that would have derailed the West’s operation in Afghanistan. Bhutto certainly believed that Washington had orchestrated the coup which toppled him. He smuggled out a testament from his death-cell which included Kissinger’s threat to ‘make a horrible example’ of him unless he desisted on the nuclear question. Many people in Bangladesh still insist that the CIA, using the Saudis as a conduit, was responsible for Mujib’s downfall. Mujib’s daughter Haseena, currently Prime Minister of Bangladesh, was out of the country and thus the only member of the family to survive. The US may or may not have been involved, but it was a remarkable hat-trick: in the space of a decade three populist politicians, each hostile to US interests in the region, had been eliminated.

After the break-up of 1971, Pakistan appeared to lose interest in Kashmir and South Asia as a whole. A young and ambitious State Department official visited the country in 1980, a year after Bhutto’s execution, and advised Zia to look towards the petrodollar surplus being accumulated by Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States. Pakistan’s large army was well positioned to guarantee the status quo in the Gulf. The Arabs would pay the bill. Francis Fukuyama’s position paper, ‘The Security of Pakistan: A Trip Report’, was taken very seriously by the military dictatorship. Officers and soldiers were despatched to Riyadh and Abu Dhabi to strengthen internal security. Salaries were much higher there and a posting to the Gulf was much sought after. Pakistan also exported carefully selected prostitutes, recruited from elite women’s colleges. Islamic solidarity recognised no bounds.

With Islamabad’s attention elsewhere, the Indian Government could have reached an amicable settlement in Kashmir. But during the 1980s India interfered in the region with increasing ferocity, dismissing elected governments, imposing states of emergency, alternating soft and hard governors. Delhi’s favourite despot, Jagmohan, was responsible for the suppression of the ultra-secular Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front and the imprisonment and torture of its leader, Maqbool Bhat. Young Kashmiri men were arrested, tortured and killed by Indian soldiers; women of all ages were abused and raped. The aim was to break the will of the people, but instead many young men now took up arms without bothering where they came from.

I had met Bhat in Pakistani-controlled Kashmir in the early 1970s. He seemed equally hostile to Islamabad and New Delhi and determined to remake a Kashmir that was not a helpless dependant of either. He was a great admirer of Che Guevara and when I talked to him, in the euphoric aftermath of the 1969 uprising in Pakistan that had led to the fall of Ayub Khan, he was dreaming of a quick victory in Kashmir. When I suggested that the rickety enthusiasm of a tiny minority was not enough, he reminded me that every revolutionary group (Cuba, Vietnam, Algeria) had started off as a minority.

The Indian authorities arrested Bhat in 1976, and charging him with the murder of a policeman, sentenced him to death. He was kept in prison as a bargaining counter until 1984, when he was executed in response to the kidnapping and murder of an Indian diplomat by Kashmiri militants in Birmingham. The vacuum he left would soon be filled by the men with beards, infiltrated, armed and funded by Pakistan.

By the late 1990s, after years of intra-Muslim factional violence, Afghanistan had come under the control of the Taliban – themselves funded, armed and sustained by the Pakistan Army. Pakistan itself was in the grip of corrupt politicians, and sectarian infighting was claiming dozens of lives each month. In India, the Congress Party had lost its hold on national politics, paving the way for the Hindu fundamentalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). In Kashmir the number of armed Islamist groups multiplied as more and more veterans of the Afghan war came across the border to continue their fight for supremacy there. The main rivals were the indigenous Hizbul Mujahideen and the Pakistani-sponsored and armed Lashkar-i-Tayyaba and Harkatul Mujahideen.† The groups killed each other’s militants, kidnapped Western tourists, drove Kashmiri Hindus out of regions where they had lived for centuries, punished Kashmiri Muslims who remained stubbornly secular and occasionally knocked off a few Indian soldiers and officials. Each group was willing when convenient to make terms with Delhi rather than combine with other groups to inflict punishment on the Indian Government. Governor Jagmohan responded by making it as hard as he could for these Muslim groups to find new recruits. Night-long house-to-house searches became a part of everyday life. Young men were abducted by Indian soldiers, never to be seen again. In his self-serving memoirs, Frozen Turbulence, Jagmohan explained: ‘Obviously, I could not walk barefoot in a valley full of scorpions. I could leave nothing to chance.’ The result of his policy was to win support for the gunmen.

Kashmir was ruled, more or less unhappily, by Delhi until 1996, when Farooq Abdullah came back to power – most of the other parties boycotted the elections. Since then his collaboration with the BJP has destroyed his remaining reputation and if a free election were permitted, his career as a politician would soon be over.

The Indian and Pakistani Armies are among the largest in the world. In September 1998, the Pakistani High Command decided to test Indian border defences in the virtually undefended Kargil-Drass region, a Himalayan wasteland 14,000 feet above sea-level where Kashmir meets Pakistan and China. The region is one of mountain ridges and deep valleys, with temperatures averaging –20°c; it is also an area colonised by wild yellow roses, which bloom for a month each summer; the petals are eaten by villagers, who believe the rose nourishes the body and heals the soul. Most of the villagers are Shiite Muslims or Buddhists who live quiet, harmonious lives, sharing, among other things, an aversion to the Sunni fundamentalist imports from next door. The Pakistani Army, wholeheartedly backed by Nawaz Sharif’s Government, crossed the Line of Control accompanied, just as it had been in 1947 and 1965, by soldiers disguised as irregulars and Lashkar-i-Tayyaba contingents, and occupied several ridges and villages. The Indian Army moved troops to the area from Srinagar and artillery duels became a daily nightmare for the locals.

Why had Pakistan embarked on an adventure of such obvious strategic futility? There was no possibility of triumphant entrances by victorious generals or politicians. Most Pakistani citizens, other than the Islamists, knew very little about what was happening in the mountains. Nor were they particularly interested in the fate of Kashmir. The real reasons for the war were ideological. Hafiz Mohammed Saeed, the head mullah of the Lashkar, told Pamela Constable of the Washington Post: ‘Revenge is our religious duty. We beat the Russian superpower in Afghanistan; we can beat the Indian forces too. We fight with the help of Allah, and once we start jihad, no force can withstand us.’ His argument was echoed by Pakistani officials. The Indians weren’t as powerful as the Russians and since they no longer possessed a nuclear monopoly in the region there was no danger that a limited war would escalate. Second, and more important, Pakistan’s actions would internationalise the conflict and bring the United States ‘on side’, as in Afghanistan and the Balkans.

In the war-zone itself, India suffered initial reverses, then brought in more troops, helicopter gunships and fighter jets and began to bomb Pakistani installations across the border. If Nato could overfly borders without any legal sanction, so could they. By May 1999, as the yellow roses were about to bloom, the Indian Army had retaken most of the ridges it had lost. A month later its forces were poised to cross the Line of Control. Pakistan’s political leaders panicked and, falling back on an old habit, made a desperate appeal to the White House.

A US general was sent to Pakistan to have a quiet word with the military, and Nawaz Sharif was summoned to the White House. Clinton told him to withdraw all his troops, as well as the fundamentalists, from the territory they had occupied. Nothing was promised in return. No pressure on India. No money for Pakistan. Sharif capitulated. His Information Minister, Mushahid Hussain, had told the press just before the Washington visit that ‘we did not start insurgency in Kashmir which is populous [sic], spontaneous and indigenous and we cannot stop it.’ But they did. The dispute had indeed been internationalised, though not exactly as Pakistan had wanted. With China as the main enemy, Washington had dumped on Pakistan and was leaning heavily in India’s direction.

In private, Sharif told the Americans that he supported a rapprochement with India and had resisted the Kargil war, but had been outmanoeuvred by the Army. The lie went down well in Washington and Delhi, but angered the Pakistani High Command. When he got home, Sharif hatched a plan to replace the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, General Pervaiz Musharraf, with one of his placemen, General Khwaja Ziaudin, Head of the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), regarded by many as the ‘invisible government’. Sharif’s brother Shahbaz made an unpublicised visit to Washington with Ziaudin in tow in order to get approval for Ziaudin’s appointment. The two men were received at the White House, the Pentagon and the CIA and made many rash promises.

On 11 October 2000, while Musharraf was on his way back from a three-day official visit to Sri Lanka, Nawaz Sharif announced his dismissal and Ziaudin’s promotion. The authorities at Karachi airport were instructed to divert the General’s plane to a tiny airstrip in the interior of Sind, where he would be taken into custody. But the Army refused to accept Ziaudin’s authority and the Karachi commander occupied the airport and ordered the plane to land. Musharraf was received with full military protocol. The Army commander in the capital arrested the Sharif brothers and General Ziaudin. This was the first coup d’état carried out in the face of explicit American instructions to the contrary: in a statement issued three days before these events, Clinton had warned against a military takeover. In Pakistan the fall of the Sharif brothers was celebrated on the streets of every city.

Musharraf pledged to wipe out corruption, restore standards in public life and, in an unguarded interview, stressed his affinity with Kemal Ataturk, the founder of secular Turkey. No restrictions were placed on the press or political parties. Nearly two years later, Musharraf’s early anti-corruption zeal has dissipated. The fiercely incorruptible General Amjad was transferred from the Accountability Bureau to a military command in Karachi: he had amassed evidence revealing extensive corruption in every institution in the country. Supreme Court judges were for sale to the highest bidder (defence lawyers asked clients for six-figure sums as the ‘judge’s fee’, payable before a trial began); many senior civil servants were on the payroll of big business and the narco-barons; businessmen pocketed bank loans worth billions of rupees; senior military officers had succumbed to bribery. Amjad insisted to no avail that the new regime clean up the Armed Forces. Unless retired and serving officers were tried, sentenced and punished, he believed, Pakistan would remain a failed state, dependent on foreign handouts and a black economy fuelled by narco-profits. His transfer shows that he lost this battle.