Illustrators of the Divine Comedy find it hard to graduate from Hell, easy going for all the arts, to Paradise, which can look dreary by comparison. The Inferno, after all, is of the earth – an interesting place – aligned with the loins of Lucifer, the gigantic armature which holds the damned in their place. Dante’s Paradise is about unmitigated light, before it drains through the spheres to the earth. Nature, St Thomas explains in Canto xiii, cannot transmit these remains of the divine day, but fumbles them ‘like an artificer/Who knows his trade but has a trembling hand’. There is far more scope for the artist in the observation of this fumbling than in the blinding effect of heavenly effulgence.

Botticelli’s illustrations for the Divine Comedy were begun about a century and a half after Dante’s death. Between 1480 and 1495, the artist followed the poet canto by canto. Ninety-two of the drawings survive and can be seen in the Sackler Wing of the Academy. It is a good idea to take the third room first, on the grounds that the dazzling decontamination chambers and the stringent out of body dress codes of Paradise were more of a challenge for Botticelli with his voluptuary eye.

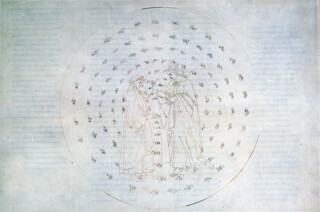

He excels against the odds. In Paradise, for the most part, the illustrations stick fast to Dante and Beatrice, with very little else to tell us where they are or what they might be about. In Canto i we see them rise from a circle of Edenic saplings towards the heaven of fire. From Canto v, they are the only human forms in prospect. As their ascent continues through the planetary spheres, the occupants of heaven assume the guise of small, decorative flames marshalled in concentric rings. The couple gaze on. They advance or recoil in ecstasy; they float or come to rest, like exquisite mime artists, reacting to beings and contingencies which to us are matters of conjecture. It’s not until Canto xxi that the emblematic flame-creatures surrounding them like votive lamps are replaced by small, putto-like figures, with limbs and so on, sailing weightlessly beside the base of Jacob’s Ladder.

But even here, the poet and his spirit-guide seem importunately human, as mime artists must. And they remain so. By Canto xxv, in the Heaven of the Fixed Stars, where John the Evangelist explains the disembodied nature of beings in Paradise, there is no doubt that Beatrice is a very material girl, her right leg bent, and forward just a touch, her left leg braced under a sidling hip.

The celebrity appearances by Adam and Saints James, John (Evangelist) and Peter take the form of little soul-flames, like the others, distinguished only by the tags inscribed beside them. The couple converse and pass on. We see the last of them as they rise through the river of light (Canto xxx). Beatrice leads the way upstream, turning her head to the poet. His arms are raised, his face is a mask of sublime consternation.

The work for Canto xxxii of the Paradise is incomplete, leaving the Queen of Heaven, Christ and Gabriel stranded on the rim of a monumental blank which would have been the Celestial Rose. They are diminutive figures in a daunting emptiness created by large-scale erasures: proof that the Empyrean is beyond depiction or description. As for the preceding Canto, there is nothing at all. Botticelli took the parchment set aside for this illustration and bore it straight to Hell. It was used for the lower half of a double-spread figure of Lucifer, in which Dante and Virgil clamber out of the Inferno (xxxiv, 2). At the groin of the huge, shaggy figure – the centre of the earth – down becomes up, as they turn through 180 degrees in order to emerge head first in the southern hemisphere.

An erasure at the bottom of the parchment tells us it had once been reserved for the Paradise cycle. The change of plan – and the touching mark of defeat – alerts us, again, to the fact that Hell is a doddle. A magnificent place, nonetheless, where the literal almost always prevails over the symbolic. Here and in Purgatory, Botticelli goes about his business with the workmanlike serenity of a war artist (so much to get down!).

The further Dante’s illustrators are from late 13th and early 14th-century Florence, the more they have to think aloud – from the bearded ancients of Blake’s Paradise to the Busby Berkeley sets of Doré’s and on to Rauschenberg’s Inferno with its oil derricks and track-and-field chastisements. For the three-headed Lucifer of the Inferno, Tom Phillips inverts three photographs of the Turin shroud and sets them on three stout necks over a single, up-ended triangular torso. From the inversion of ‘the features of Jesus’ this sinister ‘pattern of the Antichrist’, with its threefold invocation of the gangster, the paramilitary and the modern interrogator, derives ‘some residue of glory’, while the whole effects ‘a travesty of the Trinity’. No illustration, then, without imagination and interpretation – even if one needs the notes from time to time.

Botticelli’s Dante runs until 10 June. The catalogue is published by the Royal Academy (360 pp., £48, 17 March, 0 900 94685 7). Tom Phillips’s illustrations are on display in the Print Gallery.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.