The extrovert author of numerous books, including the highly enjoyable Affluent Society and Great Crash of 1929, longtime Harvard professor (now emeritus), once New Delhi’s greatest celebrity (since Edwina) as Kennedy’s Ambassador to India, witty excoriator of the scholarly pretences of his fellow economists and of all manner of other balderdash, John Kenneth Galbraith’s only reticence hides a skilfully disguised but intense puritanism. He may not suffer the classic puritan’s agonies at the thought that somebody, somewhere is having a good time, but if contentment is a goal for the rest of us, it is clearly a goad for Galbraith, for whom it is only the tolerant companion of evils that a suitably restless discontent might abolish. After reading this far from unpersuasive essay inflated into a book by means of an uncrowded typeface and thick paper, one feels morally certain that his starting point was not the derived evils, but contentment itself. And in lieu of one chapter of conclusions he has two on the inevitable punishments to come (‘The Reckoning I’ and ‘The Reckoning II’, à la Stephen King) and a final mournful coda, ‘Requiem’ – for unlike redemptionists who denounce sin and threaten hellfire only to preach and promise salvation, Galbraith forecasts an inevitable downfall of relative economic decline, further tormented by underclass uprisings of the South-Central LA variety.

His argument begins by noting that the financially contented of any society provide an eager market for economic theories that justify their prosperity, readily finding economists willing to supply them, from the Physiocrats who suited the landed interest and Malthus who served the first industrialists (by proving the demographic inevitability of subsistence wages) to Laffer, he of the ‘curve’ which explains why lower income taxes increase tax revenues. More important, the contented naturally reject ideas or facts that challenge the legitimacy or durability or societal sufficiency of their affluence, and therefore resist economic, social or political reforms – including those that end up safeguarding their best interests when carried out all the same, as most famously with the New Deal.

Historically, however, the financially contented were a small minority. As such, they were subject to sometimes intense redistributive pressures on the part of the much more numerous poor, albeit applied locally and personally and within accepted conventions (that is how apprentices and journeymen obtained entitlements from merchant-craftsmen, and landless peasants could gain some cultivation rights). And of course privileged minorities were vulnerable to occasional revolutionary upheavals or, given forms of government more or less democratic, they could be forced to accept levelling reforms imposed by electoral majorities.

The colossal achievement of contemporary capitalism, its elevation of the majority to an affluence sufficient to ensure their contentment, has eliminated each of these agencies of redistribution and imposed change. With the discontented minority powerless under a democratic dispensation, the result is an electorally-assured social stasis that would be complete were it not for the assorted enhancements and dislocations brought about by scientific and technological change (which Galbraith does not address). In contemporary America in particular, the contentment of the more or less affluent majority induces, according to Galbraith, a tacit acceptance, or even positive electoral approval, of all manner of avoidable evils from extreme income inequalities remediable by more progressive taxation to an exceptionally frivolous foreign policy. It also sanctions the intellectual and political malpractice of deficit public finance to pay for current public consumption rather than self-redeeming investment. Galbraith denounces defence spending in particular, but of course in recent years transfer payments to individuals have annually exceeded the defence budget.

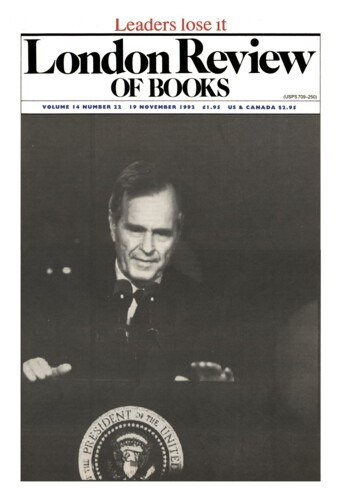

In that regard it is most revealing that even at a time of prolonged recession, and even stronger economic dissatisfactions than current unemployment or income figures would seem to justify (and they reflect very justifiable future fears), the American electorate rejected the zero-change candidate Bush only to vote for the minimum-change candidate Clinton. True, the radical-change candidate Perot was simply too bizarre to be widely acceptable. But during the earlier Democratic primaries the American public did have serious alternatives, who variously offered more public investment and protectionism to safeguard US wage levels (Kerrey), much more generous welfare programmes (Brown), or a full-scale reversion to fiscal probity and recapitalisation (Tsongas). Instead it was Clinton who won the primaries, very obviously because his campaign themes stressed his centrist opposition to any sort of change that might trouble the contented. After acknowledging that the globalisation of the US job market was leading to a convergence with Third World wage levels, Clinton nevertheless refused to oppose the free-trade treaty with Mexico; after making his obligatory visit to the smoking ruins of South-Central LA, he stayed away from inner-city scenes, and made a point of spurning Jesse Jackson’s fatal embrace on live TV; and after noting the irrefutability of the Tsongas (and Perot) calculations, he nevertheless declared the results void because they were too painful. More broadly, after challenging the Bush claims that all was well, after insisting that ‘change’ was needed, he was careful to proffer only feel-good solutions that excluded the tax increases needed for either recapitalisation or social welfare, or both. A smiling, contented man, he is a fit candidate for the contented electoral majority.

Along the way, Galbraith has mild fun exposing the hollowness of the current crop of socially-approved American myths, notably the transmutation of almost unfailingly risk-averse corporate bureaucrats into daringly innovative entrepreneurs, who must of course have the incentive of ample remuneration lest they become extinct; of every highly successful and not yet convicted financial manipulator into a bold architect of economic progress, likewise deserving of huge wealth; of perfectly ordinary military bureaucrats into hero-warrior-strategists (Hannibal-Schwarzkopf being the greatest beneficiary at present); and of congenial publicists such as George Gilder into philosophers of Heraclitean profundity.

In more sustained fashion, Galbraith also demolishes what I would call the ‘Adam Smith syndrome’. The symptoms of this especially Anglo-Saxon malady are: 1. the belief that all non-ceremonial state action is at least wasteful and often counterproductive, except to provide for the national defence on a most lavish scale; 2. the fervent conviction that all state handouts are in addition demoralising, unless given to troubled banks or (very large) corporations, farmers (often quite wealthy ones), or any other group to which the victim of the syndrome happens to belong (e.g. middle-class homeowners with tax-deductible mortgage interest payments), but in any case fatally destructive of character and self-respect when given to the poor; and 3. the delusion that Adam Smith propounded any such beliefs – i.e. that his ‘invisible hand’ implied a paraplegic state.

In the familiar manner, the victims of Adam Smith syndrome ignore the legal and indeed governmental foundations of the ‘free market’; viewing it as a celestial mechanism, they oppose all merely human interference with its divine workings, such as anti-leveraged-buyout laws that could have saved American businesses from crippling indebtedness, caused not by investment but by the perpetrators’ upfront enrichment through cash extractions and merchant-banking fees. In the same vein, they in effect impute moral purpose to the morally-neutral workings of the marketplace and go on to assume the morality of high incomes, the presumptive moral culpability of low incomes, and the outright immorality of redistributive taxation which overthrows the market’s own allocations of each.

Next, by a process of secondary infection, as it were, the victims of the syndrome become phobic not merely about redistributive taxation but about taxation altogether. Some, only a very few, are logically consistent ‘libertarians’ (their party fielded a candidate in the Presidential elections) who insist that they are willing to live in a state of nature, sans taxation or the state. But in most victims, taxphobia coexists with a lively insistence on the continuation of the many state activities they approve of, such as the national defence and the supply of services and hand-outs to themselves and whoever else is not poor (for the poor must be shielded from demoralisation). The resulting arithmetical impasse might have troubled delicate souls if complaisant economists had not come forward to resolve the contradiction, by offering supply-side theory (aka the Laffer curve, in soufflé form). Thus arithmetic was abolished, or at least the plain arithmetic of public finance was subverted, by the joyous prediction that if marginal income tax rates were lowered, reducing total revenues by X, government spending would not have to be reduced by X, because growth would be so greatly stimulated that income tax revenues would increase by at least X if not more, in spite of the lower marginal rates. The theory’s essential requirement (accelerated growth) was made into its guaranteed outcome by simply taking it for granted that: 1. people were actually not working or entrepreneuring as hard as they might because some of their incremental income would be taxed away; 2. the desire to work harder/risk more would increase in the predicted proportion; and 3. the ambient circumstances of the national and global economy would allow the conversion of imputed desires into the objective reality of higher earnings. The actual result, needless to say, has been an X-squared accumulation of public debt.

If it is so hard to believe that the Reagan crowd believed the scarcely believable there is a good reason: mostly they did not. What they did believe was that Congress would be forced to cut spending when the promised revenue alchemy failed, thereby achieving the contraction of state activity which was their real goal all along. But for a bunch of would-be cynics that was proof of an innocence truly astounding, for Congress is a mechanism designed to dilute, and not to assume, responsibility. Some others outside government who also enthusiastically applauded the supply-side gurus and the tax reductions they wrought were likewise undeceived. By purchasing high-yielding US Treasury bonds with the money left to them by tax reductions, high earners loaned their money to the government instead of paying it over in taxation, sometimes being able to become non-working public debt rentiers in the process (with-long term rates well over 7 per cent even now, and inflation below 3 per cent, the true interest rate of 4 per cent is just about the highest since Jesus Christ). The new rentiers, needless to say, showed that they were much more intelligent than supply-side economists had believed: instead of working even harder to do their bit to fulfil the promise of the theory, they retired early to crowd all the leisure spots of America, to fish, mess about in boats, golf or play tennis in the pastel Ralph Lauren outfits that are the semi-official rentier uniforms. Exceptionally contented, they are nevertheless politically very active: they are now campaigning to abolish the taxation of interest income – to remove a disincentive to frugality of course.

Galbraith is also most persuasive in defining the conduct of American foreign policy as a largely recreational activity. His evocation of the State Department’s ordinary workings, and of the élite Boston-New York-Washington foreign-policy seminars in which so often ‘policy’ is actually made (because that is where the conventional wisdom is cast and polished), reminds us how little they both matter: of the 150-plus diplomatic relationships of the United States, only a few have any importance whatsoever for all but scattered handfuls of Americans. Indeed, except in rather rare instances, the ‘foreign policy process’ in both its official and quasi-official aspects is mostly a striving to endow trivialities with significance.

As always before, Galbraith is much less persuasive in writing of military matters. In The Affluent Society he popularised the most simplistic argument against the efficacy of World War Two strategic bombing. In contending with today’s military issues, Galbraith, the puritan sophisticate, is again unsophisticated: indeed he echoes every Reagan-era anti-defence cliché going.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.