In her short film, The Food Chain (2002), Ariella Aïsha Azoulay asked Israeli officials whether the people of Gaza and the West Bank were suffering from hunger. ‘The state is humanitarian. The army is humanitarian,’ Lieutenant Colonel Itzik Gorevitch of COGAT (Co-ordination of Government Activities in the Territories) told her. ‘First of all, there is absolutely no hunger … There won’t be hunger in the territories, period.’ In the film a chorus of blindfolded actors, wearing blankets, sang a refrain: ‘There is hunger in Palestine/there is no hunger in Palestine.’ Richard Cook, a director at UNRWA, the UN Relief and Works Administration, said to Azoulay that arbitrary, banal impediments to food supplies were jeopardising the nutritional health of many Palestinians.

After 7 October 2023, the Israeli government narrowed its definition of humanitarian aid to the delivery through the Gaza crossings of foodstuffs in quantities determined by the minimum calories needed by the population within the strip’s ‘humanitarian zones’ – a small fraction of the territory where people were ordered to congregate ‘for their own safety’, their lives minutely subject to the diktats of the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) and their quadcopter drones, bombers, snipers and mobile artillery. During the past year, as starvation started to appear in Gaza, Israel has clashed with the United Nations and aid agencies over the very nature and significance of data on humanitarian catastrophe. For decades, collecting and analysing statistics on families’ food consumption, child malnutrition and other indicators of distress has been a niche field staffed by specialists, who are skilled at reading the human tragedies in the numbers. And with painstaking caution a series of reports by international and US humanitarian analysts have explained that there is indeed starvation in Gaza, despite Israel’s insistence to the contrary: the blindfolds are off.

Even in its dying days, the Biden administration followed Israel’s script to the letter. In January Jack Lew, the US ambassador to Israel, insisted that he had worked hard ‘on the humanitarian assistance side, to make a bureaucratic system and a security system work so you don’t cross over into famine or malnutrition … Frankly, I don’t think Israel has gotten credit, and I don’t think the United States has gotten credit, for keeping the situation from crossing that line.’ Washington’s own famine warning system contradicted Lew. He and a senior official at USAID had the report suppressed.

The ceasefire that came into effect on 19 January makes brief reference to a ‘humanitarian protocol’. Over each of the succeeding days, more than six hundred trucks of supplies have crossed into Gaza. It’s far more than before and shows what the aid agencies can do when the restrictions are lifted. But it’s still far short of the order issued by the International Court of Justice ten months ago: ‘ensure, without delay, in full co-operation with the United Nations, the unhindered provision at scale … [of] basic services and humanitarian assistance, including food, water, electricity, fuel, shelter, clothing, hygiene and sanitation requirements, as well as medical supplies and medical care.’

Twenty years ago in the Horn of Africa, communities stricken by hunger asked why some places were receiving more aid than others, and aid donors with limited budgets wanted to know which to prioritise. The nutritionist Nicholas Haan and his colleagues at the UN’s food security and nutrition analysis unit in Somalia developed a five-phase scale with colour-coded maps to represent a composite of three kinds of data: on households’ access to food, child malnutrition levels and increased mortality rates. This scale was used as the basis for the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification system (IPC), which has since been extended to 55 countries on three continents; nineteen humanitarian agencies contribute data to it, including the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), established by the US Agency for International Development in the 1980s, and another handful work with the IPC’s West African sibling, the Cadre Harmonisé.

The IPC’s methods and metrics were designed with African rural populations in mind and have been applied most consistently in places such as Somalia and South Sudan (the mechanism was never activated in Syria, because Bashar al-Assad’s government didn’t want to cede any control over humanitarian information). In middle-income cities, food systems are very different, and baseline mortality rates much lower. Aid workers and journalists saw this in Sarajevo thirty years ago. The level of urban starvation in Gaza has not been seen since the Dutch Hunger Winter and the siege of Leningrad during the Second World War. In 2010, the journalist Amira Hass noted some of the cruelties of COGAT’s practices:

The ban on toilet paper, diapers and sanitary napkins was lifted three months ago. A little more than a month ago, following a long ban, Israel permitted the import of detergents and soaps into Gaza. Even shampoo was allowed. But one merchant discovered that the bottles of shampoo he had ordered were sent back because they included conditioner, which was not on the list. Five weeks ago Israel allowed margarine, salt and artificial sweetener to be brought into Gaza. Legumes have been allowed for the past two months and yeast for the past two weeks. Contrary to rumours, Israel has not banned sugar. COGAT commented that ‘the policy [on bringing in] commodities derives from and is co-ordinated with Israel’s policy towards the Gaza Strip, as determined by the cabinet decision on 19 September 2007.’

Hass added that COGAT didn’t provide written lists. Instead, information about which items were permitted or prohibited was given by phone, at times that varied without warning. The routes that were open or closed also changed, sometimes daily. One day, all kinds of hummus might be allowed; the next day, only plain hummus could pass, while hummus garnished with pumpkin seeds would be blocked.

The cabinet decision that COGAT referred to is known as the ‘red lines’ document. It was obtained by Gisha, an Israeli human rights organisation, which petitioned Israel’s supreme court for three years. The Ministry of Defence had carefully examined food availability and consumption in Gaza and came up with a diet devised on the basis of a calorie count per head that would satisfy the bare minimum nutritional requirements, and this was used to determine what food – along with other essentials – would be allowed into Gaza, and when. Until Gisha won its legal battle, the contents of the document were secret, although Palestinians were conscious, every day, that they were subject to COGAT’s whim. This was a unique kind of food insecurity. Assessments before the war found that Gazan children were rarely underweight but had a restricted diet and, most important, that most families depended on food aid provided by UNRWA. Gaza’s water, electricity and health infrastructure also relied entirely on Israeli goodwill. Rarely has the wellbeing of a population been so fastidiously controlled.

In a much quoted phrase, Dov Weissglas, an adviser to Ehud Olmert, then the Israeli prime minister, said in 2006 that it was Israeli policy ‘to put the Palestinians on a diet, but not to make them die of hunger’. After the Hamas attack on 7 October 2023, this changed. In the following months, the government settled implicitly on a new red line: Palestinians might die in all kinds of ways, but not of famine, at least not according to the arcane formulas of the IPC. During its first two months, Operation Swords of Iron combined bombardment of an intensity with few if any parallels in modern warfare, far-reaching evacuation orders for the civilian population and a near total blockade of all essential commodities. There was a fierce debate over the legality of Israel’s actions, but what’s not in doubt is that humanitarian catastrophe ensued. As I have argued before in the LRB (15 June 2017), the verb ‘to starve’ should primarily be seen as transitive: something that people do to one another.

In the last week of November 2023, taking advantage of the brief ceasefire during which Hamas released 105 hostages, the aid agencies affiliated with the IPC collected data in Gaza, observing the protocols laid out in elaborate detail in their manuals. On the matter of ‘acute food insecurity’, their findings showed that most people in Gaza were struggling to survive with entirely insufficient levels of essential foods, water, shelter and medicine. An estimated 377,800 people, 17 per cent of the entire population, were in IPC phase 5 (‘catastrophe’) and a further 40 per cent in IPC phase 4 (‘emergency’): numbers that recall the nadir of the famine in Somalia in 2011. Acute food insecurity before 7 October was estimated to affect 1 per cent of the population: the speed of deterioration was without precedent over at least the previous twenty years and probably much longer than that. The vast majority of people in Gaza – 93 per cent of the population – were either in phase 3, ‘crisis’, or in phases 4 and 5: this level had never been recorded anywhere before by the IPC.

Data for malnutrition were patchy and figures for deaths from hunger and disease simply didn’t exist. The Ministry of Health in Gaza wasn’t reporting the number of children whose deaths were ascribed to malnutrition (they started doing so in February 2024, then stopped in June). An adult deprived of all nutrients but kept hydrated takes up to sixty days to die. With a few crumbs to eat each day the process is slower. The siege of Leningrad and the Dutch Hunger Winter were not the only occasions in the 20th century that helped us understand more about starvation. There was also the ‘starvation experiment’ of 1944-45 carried out at the University of Minnesota, in which volunteers were semi-starved in laboratory conditions under the supervision of a team headed by the physiologist Ancel Keys, later a champion of the sugar industry. In the Warsaw ghetto, Jewish physicians painstakingly documented the effects of starvation on the human body. Their handwritten notes, smuggled out and hidden until the end of the war, were published in English in the 1970s as Hunger Disease. They recorded how the ghetto doctors managed epidemics of typhus and tuberculosis, and the vicious interactions between malnutrition, infection, wounds, dehydration and cold. Some of their observations, for instance on ‘refeeding syndrome’ – the dangers associated with an emaciated person eating too much when she finally can – were years ahead of their time. The Israeli hostages released after fifty days in Hamas’s tunnels and bunkers showed symptoms that would have been familiar to the Warsaw doctors. Even the few who had a veneer of normality suffered from physical and psychological traumas. Adults, of course, had favoured children when allocating limited rations. (It’s to be hoped that the newly released Israeli hostages will not have their dignity compromised by details being released of their deprivations in captivity.)

Frank starvation at this scale is what the historian Cormac Ó Gráda calls the ‘modern’ pattern of famine mortality. In the ‘traditional’ model – in Ireland during the Great Hunger, in colonial India and contemporary sub-Saharan Africa – infectious diseases are the principal threat to life. Wallace Aykroyd, the first director of the nutrition division at the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation, summarised the state of the science after the famine in Biafra of 1967-70. ‘Famine has often been associated with outbreaks of disease which have killed more people than starvation itself. But this association is in the main social rather than physiological, i.e., it is due to the disruption of society, facilitating the spread of epidemic disease, rather than lowered bodily resistance to invading organisms.’

In the 19th century, typhus was known as ‘famine fever’, spread by fleas in overcrowded, unsanitary workhouses and famine shelters. In the famine I studied in Sudan in the 1980s, malnutrition was rarely identified as the cause of death. More common culprits by far were measles, malaria and diseases causing diarrhoea, which were spread by people moving around in search of food, overcrowding in unsanitary camps, the collapse of vaccination against childhood diseases – and were more lethal because so many children were underfed. Mass starvation isn’t simply individual starvation aggregated, but the collapse of human health in a collapsing society: first displacement and the disruption of water, sanitation and shelter, attended by a drop in consumption of essential foods; then child malnutrition; and in the absence of remedial health and nutrition efforts, the prospect of mass deaths.

During the war in Darfur between 2003 and 2005, deaths by violence were far more conspicuous, but were fewer by two-thirds than the toll of indirect deaths from hunger and disease. In Iraq, after the Bush-Blair intervention, the ratio leaned the other way, with only a third of victims succumbing to ‘non-trauma’ deaths, as they’re known. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, from the 1990s until the present, approximately 90 per cent of fatalities have been ‘non-traumatic’.

The weapon of starvation in the hands of a belligerent is on a lead that can be lengthened or shortened, for strategic or arbitrary reasons. COGAT put Gazans on a short lead. The practicalities of getting aid to Gaza, unlike Darfur or the DRC, are straightforward, and Israel can take action in a matter of days if it wants to. When polio was detected in Gaza last August, it reacted promptly, collaborating with the World Health Organisation to mount a highly effective vaccination programme throughout the strip. Israel acted from self-interest: the ultra-orthodox Haredi community are opposed to vaccination, leaving 175,000 of their children vulnerable to a virus that spreads swiftly and silently.

Rarely has the space for humanitarian action been as constricted as it was in Gaza when the IPC made its first assessment. The number of humanitarian workers killed around the world in 2023 was 280. Of these, 163 were in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Until then, the highest total loss per country had been 37 in Syria in 2016. The global numbers for 2024 were 344, 204 of whom died in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Relief agencies have developed sophisticated protocols for staff safety in armed conflicts, including marking vehicles and ensuring their movements are approved in advance with governments and armed groups. This is known as ‘deconfliction’. All the agencies use this process in Gaza, where Israel tracks every mobile phone and every vehicle. A single instance in which aid workers die, such as the attack on the vehicles carrying World Central Kitchen staff on 1 April 2024, which killed seven, may plausibly be called an error. Yet it’s hard to believe that the killing of so many aid workers is the result of a series of regrettable mistakes, any more than that of medical staff – 1054 killed according to Gaza’s Ministry of Health – or journalists and media workers: at least 158 according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

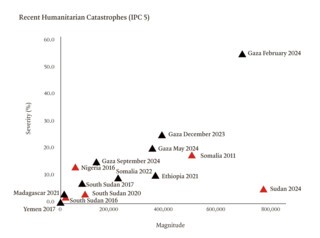

Declaring a famine, as the IPC has been on the brink of doing in Gaza on several occasions, has moral force rather than legal consequence. The IPC drew on the ‘famine scales’ drawn up by the scholars Paul Howe and Stephen Devereux. Their prototype had two dimensions. ‘Magnitude’ was measured by the number who had perished from starvation and related causes, and by extension, the total affected population. ‘Severity’ measured the intensity of starvation in a particular place. The IPC didn’t want to wait until ten thousand or a hundred thousand people had died before crying famine, and chose severity as its scale. The threshold for a ‘famine’ diagnosis is very high: one in five households in a given area absolutely without food access, 30 per cent of children suffering severe acute malnutrition and death rates of two per ten thousand per day or higher. If all three criteria aren’t met, or the people meeting them aren’t concentrated in a specific area, the IPC describes it as ‘catastrophe’ rather than ‘famine’, but for the people afflicted, this is a distinction without a difference (both classifications are IPC phase 5). It has the ironic consequence that a large population can be in a situation that falls short of ‘famine’ on the severity index even while tens or hundreds of thousands of children perish of hunger and disease. ‘Famine’ was declared in two counties in South Sudan in 2017. Several thousand perished in those places. But far higher numbers – an estimated 190,000 – died from hunger and disease across the wider area classified as IPC phase 4 ‘emergency’. Some UN staff argued that hundreds of children who drowned in the swamps while desperately gathering edible water lilies should be counted among the famine deaths, but the South Sudanese government objected. Palestinians in Gaza usually describe those killed while trying to find food – 118 were killed in the ‘flour massacre’ on 29 February 2024, twelve in a drone attack on an aid convoy in December, dozens of other cases are yet to be tabulated – as victims of famine.

Before a famine can be determined, the IPC data are scrutinised by the independent Famine Review Committee. Its half-dozen members are all volunteers, drawn from academia and international agencies, and it has met just over twenty times over the last decade, including four times on Gaza. Their analysis is scrupulously cautious; they are resistant to alarmist calls. And if the data aren’t available, they can’t determine the existence of a famine. At the end of 2016, they assessed post factum that there had been a famine in north-eastern Nigeria: the key data had only become available several months later. The IPC and its Famine Review Committee require data from all three fields of information – households’ lack of access to food, child malnutrition and death rates – to make their determination. The last are the hardest to ascertain, and the more disrupted the community, the harder it is to conduct a survey or to obtain essential baseline information such as the size of the affected population.

Advocates from the afflicted communities may complain that they are suffering famine and that the food security technocrats, in their citadel of expertise, are deaf to their entreaties – a fair point, but the more salient risk is that the political authorities don’t want the stigma of being seen to preside over famine and so block data gathering. If there’s no data, they can say the claims are made up. In Ethiopia in 2021, IPC data pointed to an impending famine in the besieged region of Tigray. The central government, which was using starvation as its weapon, expelled the IPC, and then argued that the absence of evidence for famine was evidence for its absence.

The number of people in Gaza in IPC 4 ‘emergency’ and IPC 5 ‘catastrophe’ is extraordinary. The graph below shows the numbers in phase 5 in all the cases considered by the IPC Famine Review Committee since 2014, plus Somalia in 2011. The horizontal axis is magnitude: the absolute numbers. The vertical axis is severity: the percentage of the population in the worst affected location. The cases where the Famine Review Committee has determined ‘famine’ are shown in red.

The graph shows that the Gaza numbers are outliers. It also shows that the controversy over whether or not Gaza has crossed the red line into ‘famine’ is a distraction. Since the inception of the IPC, cases determined as ‘famine’ aren’t the worst by overall numbers, just as the altitude of the highest peak isn’t a guide to the total mass of a mountain range. Technical advisers to the IPC have debated whether the threshold for ‘famine’ should be changed. Should a second dimension of magnitude – aggregate numbers rather than intensity in specific locations – be added? The latter would work on the logic that if a population is in IPC 4 for (let us say) a year, its level of deprivation will gradually add up to famine levels of mortality. (When the IPC was designed, the nutritionists and epidemiologists involved assumed that ‘emergency’ status would be transient – either aid donors would respond, or there would be a harvest and conditions would improve.) The data show another important anomaly: the figures in Gaza vary wildly over the four assessments. It’s normal for the numbers of people in need to fluctuate, in line with levels of aid, conflict and migration, and harvests, but in Gaza they shot up at unparalleled rates until March 2024. They came down in the months that followed because the system worked: the IPC showed that Gaza was on the brink of ‘famine’, at which point the US and Israel reacted.

The Famine Review Committee’s second report on Gaza was issued on 18 March 2024. ‘Famine is imminent,’ it stated, ‘unless there is an immediate cessation of hostilities and full access is granted to provide food, water, medicines and protection of civilians as well as to restore and provide health, water and sanitation services, and energy (electricity, diesel and other fuel) to the population in the northern governorates.’ In its response, Israel blamed Hamas for the catastrophe. It justified its operation by referring to the 7 October attacks and ‘Hamas’s actions within the populated areas in Gaza, such as the launching of rockets, use of tunnels or abuse of hospitals’. It accused Hamas of obstructing or stealing aid. Senator Ted Cruz challenged the USAID administrator, Samantha Power, on this issue at the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He appeared not to want any aid at all to go to Gaza and spoke of ‘videos of Hamas terrorists riding on top of aid trucks’. ‘We do not have reports from our [aid] partners of diversion by Hamas,’ Power responded. ‘Israel is not shy about presenting to us evidence of things it finds problematic, UNRWA being the most glaring example, and this is not something that has come to our attention in other ways as well. The government of Israel has eyes on everything that goes into Gaza … The system that has been in place since 7 October is the most stringent and vigilant form of surveillance that I have ever seen.’ The Senate hearing was on 10 April, at the height of press attention over famine in Gaza. After the attack that killed the World Central Kitchen staff on 1 April, Biden called Netanyahu and ‘made clear the need for Israel to announce and implement a series of specific, concrete and measurable steps to address civilian harm, humanitarian suffering and the safety of aid workers’. Aid deliveries improved and the number of people in the most severe categories decreased.

Several senators, among them Bernie Sanders and Chris Van Hollen, had threatened to invoke a section of the Foreign Assistance Act 1961 that prohibits US assistance to countries that violate international humanitarian law or block humanitarian aid from reaching its intended recipients. To pre-empt this, the White House quickly issued an administrative measure, National Security Memorandum 20, which had a more modest requirement: the US secretary of state, Antony Blinken, had to obtain ‘credible and reliable written assurances’ from Israel that it would ‘facilitate and not arbitrarily deny, restrict, or otherwise impede, directly or indirectly, the transport or delivery of US humanitarian assistance’ and then to assess whether Israel was in compliance. If it wasn’t, US weapons transfers would be imperilled. State Department human rights experts were tasked with assessing the evidence. When it became clear that its report would fail Israel, the matter was taken out of their hands. A senior adviser resigned in protest. Blinken announced the required assurance on 10 May: ‘We do not currently assess that the Israeli government is prohibiting or otherwise restricting’ aid. Much hinged on the word ‘currently’. There had indeed been an aid surge in the preceding two months, but three days before Blinken’s certification, Israel closed the crucial Rafah crossing and mounted an offensive across southern Gaza that brought aid operations to a near halt. Presumably, Netanyahu had advance knowledge of Blinken’s finding but did not wait until after the public statement before tightening the blockade. Aid deliveries dropped precipitously, first in southern Gaza, then in the north, as a team headed by Francesco Checchi, an authority on disaster epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, showed, having compiled information on all sources of food available in Gaza: pre-existing stocks, local production, commercial imports and aid. It’s the most comprehensive picture to date. The illustration above shows supplies being used up – rapidly in the north, more gradually in the south and centre – as hunger set in. There is then a respite from March until May, followed by a bigger, more sustained collapse.

The third report by the Famine Review Committee on 25 June found that increased food aid plus an improvement in water and sanitation meant that the very worst had been averted. ‘In this context,’ it stated, ‘the available evidence does not indicate that famine is currently occurring. However, the situation in Gaza remains catastrophic and there is a high and sustained risk of famine across the whole Gaza Strip.’ It emphasised that ‘whether a famine classification is confirmed or not does not in any manner change the fact that extreme human suffering is without a doubt currently ongoing in the Gaza Strip … All actors should not wait until a famine classification is made to act accordingly.’ As the IPC data became available and the ‘no famine’ finding became more probable, defenders of Israel made their case. In May, using COGAT numbers for air drops and trucks crossing into Gaza, a group of Israeli nutritionists submitted a paper to the Israel Journal of Health Policy Research arguing that the calorie count for Gaza was more than enough to feed the population. Seven months later it has still not been published. Checchi dismissed it as ‘more like a political document than a scientific article’. He argued, among other things, that the COGAT data are opaque. The trucks aren’t all full, and the data don’t cover the most crucial periods. Two professors at Columbia University Business School defended Israel on the same grounds. Their expertise is in supply chains and marketing, not famine.

Nonetheless, a headline in the Jerusalem Post on 18 June ran: ‘Experts: ICC and UN blamed Israel for a famine that never happened in Gaza – exclusive’. The story claimed that the IPC’s earlier prediction was false and malign. Israel in fact was reverting to its former approach, whose aim, as the Israeli philosopher Adi Ophir wrote in 2010, was to ‘suspend “the real” catastrophe’ in Gaza. This meant adjusting the aid flow just enough to satisfy Washington and controlling the humanitarian data to ensure a no-famine decision. As Lew made clear, the US played a key role both in drawing the line and in deciding that Israel hadn’t crossed it. Increased deliveries had an important impact, but aggregate numbers of trucks are a small part of the picture. Food distribution is more important. Food availability is not the same as food access. In his landmark book Poverty and Famines (1981), Amartya Sen wrote that ‘starvation is the characteristic of some people not having enough food to eat. It is not the characteristic of there being not enough food to eat.’ Recall that famine requires only that 20 per cent of a given population are starving. These are invariably the poorest and most vulnerable, those hardest to reach.

As Israel mounted a campaign to restrict and then to shut down UNRWA – the one institution capable of reaching everyone – and systematically killed policemen on the grounds that they were affiliated with Hamas, it created a free-for-all. One element in the 29 February flour massacre appears to have been that traders couldn’t establish a safe system. Israel, at best, made no obvious effort to create an alternative. Mafia-style gangs run by prominent families stole food, fuel and anything else. Meanwhile, Israeli soldiers shot both aid workers and people trying to collect aid. In a press release dated 6 January this year, the head of the UN Office for the Co-ordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Tom Fletcher, wrote that ‘statements by Israeli authorities vilify our aid workers even as the military attacks them. Community volunteers who accompany our convoys are being targeted. There is now a perception that it is dangerous to protect aid convoys but safe to loot them.’ It’s indeed possible that Hamas is stealing some of this aid and hoarding it, as Israel alleges. But the procedures used in humanitarian emergencies around the world – providing UN agencies with protection, allowing monitoring and reporting mechanisms – have been systematically precluded by Israel. The breakdown of law and order in Gaza will be a huge impediment to humanitarian efforts during the ceasefire.

Palestinians in Gaza have been reduced to eating famine foods – things that are often barely edible. Some are scavenging or eating animal fodder. There has been high demand for wild plants, such as common mallow, known locally as khubeza, a green leaf described as somewhere between spinach and kale. A reliance on aid rations is also demoralising. In a recent column for Middle East Eye, the Palestinian professor Ghada Ageel quoted Hamed Ashour, a neighbour in the Khan Younis camp, who wrote on Facebook:

We received three eggs as a meal for three displaced families staying with us in the house. Believe me, I am not writing this to complain, but we now face the challenge of distributing three eggs among twenty people. Who can turn this into a mathematical equation that leads us to a solution – one that is both practical and satisfying – so we can overcome hunger together?

Ashour is right: mass starvation cannot be reduced to a mathematical equation. It’s an act as well as an outcome and its effects are much broader than limiting the calorie count. These two critical points can be found in the definition of the war crime of starvation, enshrined in Article 8(2)(b)(xxv) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, adopted in 1998: ‘Intentionally using starvation of civilians as a method of warfare by depriving them of objects indispensable to their survival, including wilfully impeding relief supplies as provided for under the Geneva Conventions.’ There is no legal definition of famine, but there is one for starvation, and this is it.

The crime of starvation has not yet been tested in a court, so there is no case law. But it is deemed to be committed when people are intentionally deprived. There’s no requirement that anyone should have starved to death, though an authoritative determination of famine would certainly lend gravity to the charge. ‘Objects indispensable to survival’ include not only food but water, healthcare, shelter, sanitation and care for the young. ‘Impeding relief supplies’ is included in the prohibition but is not its main focus. The crime against humanity of extermination is defined in the same statute, and prohibits the ‘intentional infliction of conditions of life, inter alia the deprivation of access to food and medicine, calculated to bring about the destruction of part of a population’.

The Genocide Convention prohibits starvation in Article 2(c), which reads: ‘deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part’. This differs from the crime of extermination in a crucial respect: genocide is the attempt to destroy a group as such. Does the physical destruction of a group require the death of its members? Or is it sufficient for the group to be physically dismantled, by dispersion, or by the irretrievable sundering of the social bonds that tie its members together? In an essay on the siege of Leningrad in Hunger and War: Food Provisioning in the Soviet Union during World War Two (2015), Rebecca Manley writes about the language city-dwellers developed for starvation. The words in the rich Russian lexicon for hunger all had associations with famines that particularly afflicted the peasantry. When starvation affected urban intellectuals, they used the expression ‘nutritional dystrophy’, which came to signify not just a biological state but a social and psychological condition. In her fictionalised diary of the siege, Notes from the Blockade, Lydia Ginzburg, who lived through it, wrote that ‘dystrophy, the emaciated pharaonic cow, devoured everything – friendship, ideology, cleanliness, shame, the intelligentsia’s habit of not stealing whatever is lying about. But more than everything, love. Love disappeared from the city, much like sugar or matches.’

The legal scholar Tom Dannenbaum describes siege starvation as ‘societal torture’. By weaponising a human being’s will to put an end to unbearable pain, the torturer compels the victim to betray their friends and family. ‘Siege starvation,’ Dannenbaum writes, ‘is not merely an anomalously slow mechanism by which harm or death is inflicted in war … It is better understood as a process by which biological imperatives are turned against fundamental human capabilities in a manner more normatively reminiscent of torture than it is of a kinetic attack.’ Historians and anthropologists who have recorded the daily cruelties of famine – Breandán Mac Suibhne on Ireland, Pitrim Sorokin on the post-revolutionary Russian famines, Colin Turnbull in his ethnography of the Ik of Uganda, Janam Mukherjee on the 1943 Bengal famine and Cormac Ó Gráda in his encyclopedic writings – describe a descent into a space between life and death, where moral judgment becomes impossible. Primo Levi called it the ‘grey zone’. In January, the IDF’s chief psychiatrist, Lieutenant Colonel Lucian Tatsa-Laur, claimed that an Israeli hostage held by Hamas would be ‘stripped of all his humanity and all of his being … you are starved, and you are also manipulated psychologically and physically.’ The US journalist Arwa Damon posted a remark by a friend in Gaza on Facebook: ‘They have reduced us to what they want us to be … subhumans living in filth. They don’t need to kill more of us. We are already the walking dead.’ While the labour of killing by starvation is onerous for the perpetrator, the task of destroying a community can be devolved to the victims in a familiar sequence: after massacre and mass starvation comes anarchy.

By October last year, the situation in northern Gaza was deteriorating again, with a tightened siege and intensified Israeli attacks. Normally, the IPC and the Famine Review Committee await new data before releasing a statement, but data-gathering in northern Gaza had become impossible and the Famine Review Committee took the unprecedented step of issuing an alert although it didn’t have new statistical updates. ‘There is a strong likelihood that famine is imminent in areas within the northern Gaza Strip,’ it wrote on 8 November, and called for immediate action. Four days later USAID followed suit: FEWS NET promised to collaborate with the IPC on a new famine assessment. On 23 December it published a report: ‘Gaza Strip Food Security Alert: A famine (IPC phase 5) scenario continues to unfold in North Gaza Governorate’. A senior USAID official had ‘strongly’ recommended that the report be headlined ‘risk of famine’, which would have allowed the Biden administration to claim that it had averted actual famine, but FEWS NET refused to back down. Its report was available online for a few hours but then disappeared at USAID’s instigation. The clause allowing USAID, headed by Power, a former journalist and celebrity activist against genocide, to override FEWS NET had existed for forty years but had never before been invoked.

During the brief period the FEWS NET report was online, Lew published a statement on the website of the US embassy in Israel objecting that the figures were out of date: ‘It is now apparent,’ he wrote, ‘that the civilian population in that part of Gaza is in the range of 7000-15,000, not 65,000-75,000 which is the basis of this report … relying on inaccurate data is irresponsible.’ That’s demonstrably false: the suppressed report – which survives on the internet’s Wayback Machine – stated that ‘an update from [UNRWA] on 22 December suggests the population may be as low as 10,000-15,000.’ The population in northern Gaza was reduced by the killing of Palestinians and the creation of conditions under which human life was impossible, forcing the inhabitants to leave through an act of starvation.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.