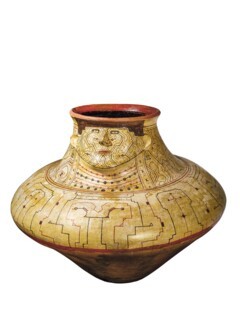

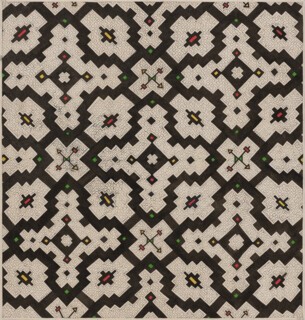

The Shipibo-Konibo people, who live along the banks of the Ucayali river in Peru, are one of several Amazonian groups whose art is intimately connected to their use of ayahuasca, a vision-inducing brew of jungle vines and leaves that contains the mind-altering compounds harmaline and dimethyltryptamine (DMT). Their textiles and ceramics are characterised by kené, geometric patterns that represent the life energy of the ayahuasca plants, which are absorbed by those who drink the brew. Kené means simply ‘design’, but the patterns themselves are far from simple, with thick lines forming complex grids that are filled by series of finer lines. To Western eyes, they resemble the maze-like etchings on an electronic chip.

Kené aren’t straightforward representations of the visual patterns generated by ayahuasca intoxication. Neuroscientists can explain the way DMT induces geometrical patterning across the visual field, but the meaning of the kené is distinctive to Shipibo-Konibo culture. One of the Shipibo-Konibo artists interviewed for the Sainsbury Centre’s exhibition catalogue describes them as part of the Shipibo worldview, ‘which integrates space, earth (forest), water, fire and wind’. Explanations of this kind can sound like platitudes, but they reflect an Amazonian notion of perspective that is difficult for us to grasp. Anthropologists such as the Brazilian Eduardo Viveiros de Castro have described it as an ontological shapeshifting whereby the observer in an ayahuasca-induced state no longer experiences the world from their habitual point of view but from that of the plants or animals they are observing, thereby becoming them.

The Shipibo-Konibo textiles and ceramics on display at the Sainsbury Centre form the core of Ayahuasca and Art of the Amazon (until 2 February), an exhibition transferred, with some additions, from the ethnographic museum at quai Branly in Paris. It traces the growth of ayahuasca from an Amazonian practice to a drug of global interest. Since the 1950s, when William Burroughs visited in search of ayahuasca – ‘the ultimate fix’ – traditional representations have been joined by those of outsiders, and ayahuasca now pervades an international genre of psychedelic art in which Indigenous Amazonian themes merge with tropes of Eastern mysticism, science fiction and computer-generated fractal geometries. At the same time, a new generation of Amazonian artists has responded by feeding these tropes back into their work, adapting their designs to appeal to lucrative Western markets.

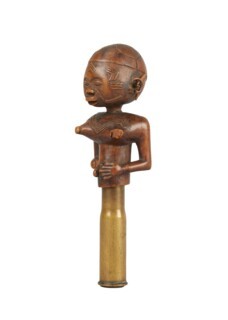

Similar journeys from the local to the global can be observed in the smaller accompanying exhibition, Power Plants: Intoxicants, Stimulants and Narcotics, which features a selection of artefacts generated by drug habits across the globe. Some of these – palm wine vessels from Central Africa, or betel-nut chewing accessories from Papua New Guinea – accompany a practice that remains largely confined to its Indigenous cultures. Others show localised elaborations of drug habits that have long since gone global (a collection of snuff tobacco utensils by Zulu and Xhosa craftsmen, the highly ritualised layout of a Japanese tea ceremony) or catch a drug culture in transition. Bowls used for the ceremonial drinking of kava, a cloudy liquid suspension of narcotic pepper root which is consumed across the islands of Melanesia, are accompanied by modern cellophane packages of kava powder, which is sold to markets including the US, where themed kava bars can be found in student and hipster neighbourhoods as a more relaxed alternative to Starbucks.

The most visually striking pieces on display in Power Plants are the yarn paintings of the Huichol people of northern Mexico. These are created by pressing brightly coloured threads onto a wooden board spread with beeswax, and depict animals and plants – deer, hummingbirds and the mescaline-containing peyote cactus – which are often outlined in red and gold and dance across fields of stars and geometric patterns. The yarn paintings have become established classics of both Indigenous and psychedelic art, commanding high prices in galleries from London to Tokyo, and the income they raise is now central to the Huichol economy. But they bear little resemblance to the traditional works from which they derive. Robert Zingg, the anthropologist who introduced Huichol art to the West in the 1930s, collected not yarn paintings but gourd and clay bowls, decorated with patterns in subdued earth tones and designed to be left as votive objects in sacred spots. Creating such pieces for sale was unthinkable. It was only in the late 1960s, when the anthropologist Peter Furst asked Huichol artists what their designs signified, that they began to include figurative subjects, spelling out narratives that had previously been implicit. The arrival of synthetic aniline dyes spurred the transition to ‘psychedelic’ coloured yarns, and it was allegedly an art dealer in Guadalajara who advised them to mount their work on ply or hardboard instead of tree bark or rough planks, in order to facilitate transport and gallery sales. For the Huichol, the new artworks are still ritual creations that mediate between the human and non-human worlds, but they are also a co-creation with the Western gaze and a commercial product.

Huichol art is commonly assumed to be a representation of the visions induced by peyote, but as with ayahuasca the relationship between the experience and the art is not so simple. The most literal representation of drug-induced visions on show is a virtual reality installation by the French filmmaker Jan Kounen, Ayahuasca: Kosmik Journey (2019). In places it captures the visual component of the ayahuasca experience with striking precision – the seething mass of serpents that assails the viewer in the opening phase has a properly claustrophobic intensity – but the dancing fractal animations into which the trip resolves eventually become generic eye candy. There’s a difference between watching a visual spectacle, however elaborately realised, and experiencing it in your own mind. Unlike with ayahuasca, you can always just take the headset off.

The emphasis on visual experience is one of the ways in which the Western category of ‘psychedelic’ can mislead when approaching the Indigenous cultures of mind-altering plants. As a Huichol shaman explained to the anthropologist Barbara Myerhoff in the 1960s, the visions induced by peyote should not be allowed to predominate: their beauty is a gift from the plant but it’s also a distraction from the deeper experience, a snare for the unprepared mind. Ayahuasca’s traditional users attach at least as much importance to the ‘purge’, the emetic effects of the brew which clean out blockages and bad spirits. At the Sainsbury Centre, there is a warning notice outside the booth showing footage of a Shipibo-Konibo ceremony: ‘Please be aware that this video shows people taking ayahuasca and vomiting.’ The purge is regarded by Western users as an undesirable side effect, but emetic plants are central to the pharmacopeia of rainforest people who battle against intestinal parasites. In Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon (2009), Stephan Beyer speculates that the combination of plants in the ayahuasca brew may have been developed for its spectacular purgative qualities as much as its visionary ones.

The global spread of ayahuasca has been driven by two overlapping beliefs in its possibilities: as a life-changing spiritual experience and as a miraculous healing intervention. Both of these bear an at best oblique relationship to its traditional use. In the Amazon, ayahuasca is most commonly used at sub-psychedelic doses, by children as well as adults, with no expectation of insight or transformation. It is deeply implicated in healing, but within a paradigm where sickness is regarded as spiritual rather than biological. Shipibo-Konibo healers see the body as covered in kené, the patterns of which are used to visualise the ‘air’ or aura surrounding a person. Bad or dark air can be sucked out with the aid of tobacco smoke. Tobacco and ayahuasca help the shaman to produce flema, a ‘phlegm’ they can project into the patient’s body, which contains virotes, darts deployed to attack the source of the dark air: these may be invisible, or may take the material form of tree spines, porcupine quills or stinging caterpillars. The invisible cause of illness is often revealed to be a curse placed on the victim by an enemy.

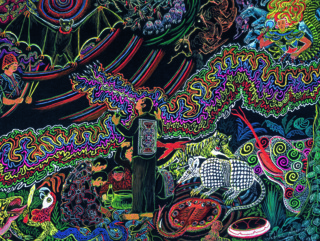

The engagement of ayahuasca art with global modernity began with Pablo Amaringo, a mestizo ‘artist-shaman’ from Pucallpa in the Peruvian Amazon, several of whose large and crowded canvases are displayed here. In the 1980s Amaringo collaborated with the anthropologist Luis Eduardo Luna, much as Furst did with his Huichol subjects in the late 1960s, with similar results. Under Luna’s guidance, Amaringo began to incorporate more pictorial and figurative elements into his work, creating extravagant scenes that included Western motifs such as UFOs, hi-tech surgeries and bodies depicted in X-ray, alongside iconography of anacondas, jungle vines, tropical birds and rainbows. Within a decade Amaringo’s work was being shown on the international art circuit to great acclaim. A younger generation of artists adopted his vivid style, inserting familiar psychedelic motifs into their work – spirals, fractals, disembodied eyes – and extending them into new media. The Shipibo-Konibo section of the show includes contemporary sculptures of jungle fauna such as anteaters, rendered in fibreglass and decorated with kené.

Writing about the use of psychoactive mushrooms in the Mazatec culture of southern Mexico, Claude Lévi-Strauss suggested that they should be understood as ‘triggers and amplifiers of a latent discourse that each culture holds in reserve and for which drugs can allow or facilitate the elaboration’. The kené may be prompted by the visual patterning seen by the ayahuasca drinker, but the art isn’t determined by the drug’s effects; similarly, a new generation can reflect a changing world without compromising their cultural inheritance.

In the 1980s the anthropologist Angelika Gebhart-Sayer suggested that the kené are actually musical scores, denoting the chants sung during ayahuasca rituals. This explanation was adopted by Shipibo-Konibo traders, who hummed the chants while selling the textiles to foreign customers. Subsequent ethnographers have questioned this explanation, which appears to be a recent introduction, yet it has established itself not just among tourists and anthropologists but among the Shipibo-Konibo themselves. In his essay for the exhibition catalogue, the curator of the Paris show, David Dupuis, argues that the power of motifs such as the kené emerges from deep communal immersion in the ayahuasca state: they are keys or ciphers that ‘enchant’ by unlocking a shared experience. They are ‘devices for making us see rather than images made to be contemplated’: a matrix not for looking at, but looking through. Western psychedelic art can incorporate these motifs, but copying the pattern doesn’t copy its meanings. In contrast to Indigenous art, which binds the individual more tightly into the weave of their shared traditions, ‘globalised shamanism’ promises an escape from the dominant paradigm of materialism, in which the patterns manifested by ayahuasca are ‘hallucinations’, by definition unreal and even pathological. If the kené enchant, the aim of Western psychedelic art is to re-enchant.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.