In the autumn of 1928, a previously unknown painting turns up on the London art market. It belongs to a Major Henry Howard of Surrey. He is 45 years old. His father has just died and left him a large estate, and he’s selling off much of it – houses, land, family heirlooms. There are death duties; he has five young daughters and a marriage that’s going to end soon. He needs cash.

Howard is knowledgeable about art. He’s a serious connoisseur and collector, an expert on Wenceslaus Hollar, the prolific 17th-century Bohemian printmaker. Among his inheritance is the family’s great collection of paintings, including first-rate 18th-century portraits by Thomas Gainsborough, Joshua Reynolds, Arthur Devis, John Opie, Jonathan Richardson and Richard Cosway, among others. The small, unattributed canvas he disposes of in 1928 is not in the same league. But it does come with an intriguing back story. Most of Henry Howard’s family’s wealth originally came from sugar plantations worked by enslaved people in Jamaica. And this portrait had been owned by a famous ancestor, of whom they are very proud, an 18th-century planter and writer called Edward Long.

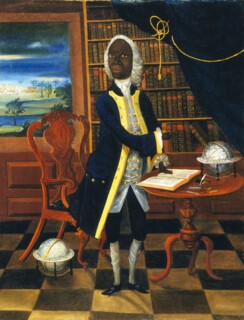

So when Howard takes the painting to a London dealer, he explains that it had belonged to his great-great-great-grandfather, who had lived in Jamaica in the mid-18th century; that it was painted in Spanish Town, the colony’s capital; and that it showed a man called Francis Williams, about whom Long had written a whole chapter in his celebrated History of Jamaica (1774). Not only that, he says, but when Long was writing that chapter, he had this painting in front of him and was describing it.

The dealer, Jack Spink, is delighted to have this information and uses it to advertise the picture. He recognises it as an unusual object, with excellent ‘associative’ value, and is sure it will make a quick sale for a good price, probably in America. They like this kind of thing over there. He has some leaflets printed and takes out a full-page advert in Country Life. At the top is a photograph of the painting, and beneath it a lengthy extract from Long’s chapter about Francis Williams – the first two and a half pages of it, no less, in tiny but legible print. That’s the only description provided. To the Howard family, and to Spink, Long’s words explain this picture. It’s an understandable presumption, since pretty much all that is known about Francis Williams comes from Long’s ten-page chapter about him. It remains the only detailed contemporary account of his life, and it was written by someone who had known him.

The problem is that Long was, in fact, Williams’s greatest enemy. His potted biography was a malicious hatchet job, full of lies and half-truths, that sought to bury rather than to commemorate its subject. Long’s huge, three-volume History of Jamaica wasn’t really a ‘history’ at all. Angrily composed in the aftermath of the Somerset ruling of 1772, which had undermined the certainty of slaveholding in England, it was above all a defence of West Indian slavery as ‘inevitably necessary’ and an attempt to prove that all ‘black’ people were naturally inferior to the ‘white race’.*

It is ironic, therefore, that Long is our main source about Francis Williams, who in his lifetime (he died in 1762) had been the most famous Black person in the world, at least among educated English-speaking people. He was rich; he was a gentleman; he was a scholar; he was celebrated as a clever and accomplished person. His memory lived on after his death. In 1774, when trying to argue that Black people were inherently less intelligent than ‘Whites’, Long had to accept that his readers would already know about Williams. He was forced to write about him because, to prove his theory of innate white superiority, he needed to take him down.

Francis Williams was born a slave on a Jamaican plantation in the 1690s. His parents, John and Dorothy Williams, were enslaved Africans. They gained their freedom when Francis was a young boy, and eventually, as successful merchants in Spanish Town, became rich enough to send him to England to continue his education. Like most wealthy free people of colour in slave societies, they themselves bought and sold enslaved people. When Williams returned to Jamaica in 1724, after spending almost fifteen years in England, he inherited their wealth, their lands – and their slaves.

Long, who was born in 1734 and only arrived in Jamaica in the late 1750s, gives a garbled account of all this in his History. He also refers in passing to other information about Williams that must have been widely known at the time. For example, he notes that Williams composed elaborate poems in Latin – then the most prestigious form of literary expression among learned gentlemen. In an attempt to denigrate Williams’s abilities, Long printed one of these, a series of verses addressed to the Scottish politician George Haldane, who had arrived in Jamaica as its new governor in 1759. It’s a striking piece, in that although the first half eulogises Haldane, the second half is about Williams himself, and what he represented. It celebrates his having been born in Jamaica and educated in Britain. It speaks proudly of his Black Muse, Black mouth and Black skin. And it argues against racial prejudice: ‘God has given the same soul to all kinds of men … virtue itself has no colour, nor does understanding; there is no colour in an honest mind, none in artistic skill … upright morals adorn the black man, and desire for learning, and eloquence in his learned mouth.’ This is now the only text by Williams that survives. If Long hadn’t tried to ridicule it, it would have been lost for ever, like all his other writings.

Long also mentions in passing that Williams had studied at Cambridge. He tries to dismiss him as a mediocre student: ‘He was fixed at the University of Cambridge, where he studied under the ablest preceptors, and made some progress in the mathematics.’ But again, his sneer records something that is not attested anywhere else. This is what historians call the problem of the archive. Our surviving written and visual materials from the past are not neutral. They don’t do equal justice to different people and groups. On the contrary, they perpetuate the disparities of the past. And this is a particular problem for the era of the transatlantic slave trade. Millions on millions of men, women and children were kidnapped, enslaved, systematically abused and murdered yet the only now remaining traces of their lives were created by people who treated them as disposable ciphers. We have to engage with this hostile and dehumanising evidence in order to speak about the enslaved and the silenced because we have almost nothing else, but it’s extremely problematic material.

In 1928, none of this matters to anyone. The extract from Long’s text that is used to advertise and explain Williams’s picture is a racist diatribe. It makes fun of a Black man presuming to dress as a gentleman, or behaving as a scholar, or trying to discuss geometry. It scoffs that ‘African’ and ‘Negro’ brains simply couldn’t cope with abstract mathematical problems: attempting to understand such things would only drive them mad. When Long made these assertions, in 1774, they had been controversial: he was himself pushing back against growing sentiments about the equal humanity of other-skinned people. But by 1928, at the zenith of empire, scientific racism has carried the day in England. No one bats an eyelid. They look at this painting and see what Long wanted them to see: a ridiculous figure, a Black man pretending to be an intellectual.

The National Portrait Gallery says it is not interested in the picture. It is bought by the Victoria and Albert Museum, the national collection of decorative arts and design – because of its fine rendition of an 18th-century mahogany table and chair. It is hung in the furniture galleries, alongside woodwork from the period. The curator who acquires it, Harold Clifford Smith, is an upper-middle-class Englishman straight out of central casting: the son of a wine merchant, educated at public school and Oxford, devoted to his old college, a regular contributor to Country Life. During the Great War, he serves in the intelligence corps; in civilian life he owns a large house in Holland Park and an Old Rectory in Berkshire. The 18th-century canvases on his own walls are valuable canine portraits by George Stubbs. Clifford Smith dates the new acquisition to around 1735 and explains to the world that it is clearly a mockery of ‘poor Williams’, a ‘curious satirical portrait’ recording a failed ‘experiment in Negro education’. But he’s very excited about its excellent depiction of a table and chair.

For almost a century, this interpretation of the picture has affected the way people see it. When it was rediscovered by modern scholars in the 1990s, many distinguished commentators presumed that it was a caricature. ‘It was clearly an exercise in mockery,’ Chinua Achebe wrote in 1998, ‘intended to put him in his place.’ At the start of the 21st century, two scholars produced pathbreaking new work on Francis Williams, finally expanding on Edward Long’s problematic account. Neither of them could decide about the painting’s meaning, however. Vincent Carretta suggested that it might well be a satire; John Gilmore, in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, simply ignored it. Though the V&A eventually moved the picture out of the furniture galleries, its modern curators, too, didn’t know what to make of it. The museum’s constantly changing public descriptions have always left open the possibility that it was a deliberate mockery.

Apart from the fact that it was previously owned by Long, this reading of the image rests on the imperfections in the way Williams’s body is portrayed: the hands are crudely delineated; the legs look strangely thin and out of proportion. But the suspicion that this might be a caricature is also shaped, inescapably, by our collective awareness of centuries of racist visual polemic. Lay and expert viewers of varied backgrounds have instinctively worried that the portrayal of Williams might fit into the long tradition of Western image-making that denigrates Black bodies for white entertainment. In 2018, when the painting was included in a landmark Brazilian exhibition of Afro-Atlantic art across the centuries, it was warily presented as ‘a Europeanised travesty … perhaps [made] with satirical intentions’. Since the 1990s, though, some art historians have presumed that the painting is a realistic portrait, albeit of a distinctively colonial character and quality. Last year, the art historian David Bindman, who has studied the picture closely for thirty years, proposed that it is in fact a self-portrait, painted by Williams himself.

What is the intent of the image and what is created by its beholders? The problem of Francis Williams’s portrait shows the degree to which personal identity depends on both. Three hundred years after Williams lived, it remains especially true for people of colour in the white world: the way you present yourself to others and the way you are perceived are two different things. But the more basic reason for the huge range of opinion about whether this painting is an honest portrait or a caricature is that we have no hard evidence about it at all.

The only certainty about the picture is that it shows Francis Williams. No one has ever been able to discover who painted it, when, where or why. Two years ago, at the instigation of David Bindman, Catherine Hall, Esther Chadwick and myself, the V&A subjected the canvas to a lengthy, state-of-the-art scientific examination. Frustratingly, its published report could not answer any of these questions.

And then, a few months ago, everything changed. On a hunch, I asked the V&A for the ultra-high-resolution scans that had been made of the painting’s surface. Within a few hours of opening those on my computer I found something completely unexpected. And that in turn catapulted me into the most exciting series of intellectual discoveries I have ever made.

This was not a fluke. When I first started looking at the painting years ago, three things had jumped out at me that no one else seemed to have noticed. I had been puzzling over them ever since. The problem was that I didn’t know what they meant. Even standing in front of the picture itself for hours didn’t help. It’s behind glass, it’s not in great condition and it’s hard now to decipher all its intricate details with the naked eye. All I had was an intuition – until I started looking at those high-resolution scans.

In 1771, nine years after the death of Francis Williams, a tiny snippet of information about him surfaced in the London press. It was published in the Gentleman’s Magazine, one of the most widely read periodicals of the time, in the Caribbean as in England. On his remote plantation in the west of Jamaica, Thomas Thistlewood carefully copied into his diary the lines about Williams. In England, while composing his History, Edward Long must have read them too. Three years later, his chapter about Williams would make no mention of the facts that they had revealed – but one could go so far as to say that his own account was a rejoinder to them.

The Gentleman’s Magazine piece was called ‘Strictures on Mr Hume’s Character of the Negroes’. In 1753, while Williams was still alive, David Hume had published a revised version of one of his celebrated essays, on ‘National Characters’. In a lengthy new footnote, he asserted that ‘negroes’ were in every way ‘naturally inferior’ to ‘whites’. He claimed that there never had been, and never would be, a single Black person distinguished in either arts or sciences. We know nothing about the composition of this tirade, except that Hume had been in touch with his friend Adam Smith about the updates he was planning. Perhaps it was Smith who pointed out the obvious counter-example of the famous Francis Williams. In any case, the final sentence of Hume’s footnote trains its sights on Williams, dismissing him as a freak: ‘In Jamaica indeed, they talk of one negro, as a man of parts and learning; but ’tis likely he is admir’d for very slender accomplishments, like a parrot, who speaks a few words plainly.’

Later scientific racists, including Long, invariably quoted Hume as a great authority. But others strongly disagreed. In 1771, for example, the piece in the Gentleman’s Magazine was an extract from a new book by the philosopher and abolitionist James Beattie, criticising Hume and arguing for the equal intellectual capabilities of all races. Beattie himself didn’t mention Williams, but at the end of the extract, the Gentleman’s Magazine added a brief, anonymous comment that did. It was written by someone who’d known Williams when he had lived in London as a young man, and it highlighted his intellectual talents. It mentioned that Williams had been friends with several ‘men of science’; that he’d attended meetings of the Royal Society; that he had been proposed for election to its fellowship; and that he had been ‘rejected solely for a reason unworthy of that learned body, viz. on account of his complection’.

The Royal Society’s rejection of Williams on racial grounds happened in the autumn of 1716. It was a scandal. It was still being talked about as a scandal in the 1720s. It was still remembered in the 1770s. It’s a significant fact. But there’s a more fundamental fact: Williams’s abilities were such that he was considered worthy of election. And that meant he had serious support among senior members of the society.

The minutes of the meeting at which he was formally proposed seem to show that. It was attended by an unusual constellation of scientists, almost all of whom had studied or taught at Cambridge. Williams was proposed by Martin Folkes, a young polymath, just a few years older than Williams himself and particularly distinguished in mathematics and astronomy. Also present were Folkes’s close collaborator Robert Smith, another youthful mathematical prodigy, who had just been appointed to Cambridge’s Plumian Chair of Astronomy, and a third leading young Cambridge Newtonian, James Jurin. Both Jurin and Smith had been given special permission to attend this particular meeting, as they were not yet fellows.

Then there were three older men, already acclaimed as scientific giants. The first was William Whiston, Isaac Newton’s successor as professor of mathematics and astronomy at Cambridge and one of the most important exponents of Newton’s new theories of physics. Next, Edmond Halley, Newton’s closest collaborator for many decades and the editor of his great, groundbreaking work, the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687). Halley was another immensely versatile scientist, whose most advanced work was on comets. And presiding over the meeting was the president of the Royal Society, Isaac Newton himself, who had recently published a second, expanded edition of the Principia.

In 1716, Francis Williams, who was then about 21 or 22 years old, knew all these people, could hold his own among them and was esteemed by many of them. That is proof of a very rarified level of scientific ability.

What exactly might this have meant? In the early 18th century, the cutting edge of scientific inquiry was the study of physical objects and the way they behaved, both on Earth and in the skies. We call this physics and astrophysics; Newton and his contemporaries called it natural philosophy. For various reasons, natural philosophy was the hardest and most prestigious form of intellectual endeavour. For one thing, it was about figuring out how the universe worked: the biggest questions of all. For another, grasping the workings of the universe meant understanding God’s laws and actions. For Newton, Whiston and other scientists, as for devout Christians more generally, the spiritual and theological implications of astronomy were profoundly important. And finally, natural philosophy was highly prestigious because the mathematics involved, especially in astronomical calculations, were very, very hard.

In 1687, Newton’s Principia had put forward a revolutionary new hypothesis that eventually transformed science – a unified theory of motion, and of gravity, the invisible force that governed the universe. His book was written entirely in Latin, the international language of higher learning, and used complicated mathematical formulae that only the most advanced scientists could grasp. Probably only a few dozen people in the world could understand it all. (Even John Locke, one of its earliest reviewers, admitted he could not.) It wasn’t until 1714 that a copy made it to North America; by 1726 there were only three. John Winthrop, the brilliant young professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at Harvard, didn’t read the Principia until he was appointed to that chair in 1738. Half a century after its publication, only a handful of colonial mathematicians were sufficiently skilled to grapple with the book’s fiendishly difficult new forms of calculus. As in England, though the text and its author were endlessly referred to, their principles became largely known only at second hand, through the work of Newtonian popularisers.

The climax of the Principia, Book 3, concerns the application of the new theory of gravity to the motions of planets and other astronomical objects. And the most advanced mathematical proofs that Newton proposed had to do with comets. These mysterious objects were at the heart of Newtonian physics: two of them were crucial to it. The first was the so-called ‘great comet’ of 1680. Newton had observed that when the comet passed behind the sun, its trajectory was bent by some invisible force. This observation led to his theory of gravity, as he celebrated in the Principia by including a large engraving of the comet’s arc. That same comet also featured prominently in the grand monument that was erected to Newton in Westminster Abbey in 1731, a few years after his death.

In the first edition of the Principia, Newton hadn’t been able to fully explain comets or to fit them properly into his theory of gravity. It was Halley who subsequently made a series of breakthroughs. Using centuries of observational data, he speculated that some comets might return every few decades or centuries, meaning that you could measure the effects on their orbits of the gravity of the planets they flew past. That would explain their changeable trajectories, as well as the variable timing of when they returned past Earth. In 1705, Halley predicted that, if he was right, a comet last seen in 1682 was likely to show up again around 1758. This became known as ‘Halley’s comet’.

Much remained unknown. Throughout the 18th century, computing cometary orbits and interpreting their role in the universe remained one of the hardest mathematical and scientific problems. Comets appeared randomly and were hard to glimpse from Earth; they travelled many millions of miles through space and their trajectories were unpredictable. Understanding them depended on a huge collective, international scientific effort. It could only be done by collating and analysing vast amounts of data from around the world. Slave forts on the African coast, the plantations of American and Caribbean colonists and naval convoys en route to the East Indies all funnelled useful observations back to the Royal Society and its Continental counterparts. European scientific endeavour, even of the most benign and abstract kind, was always heavily indebted to imperial force.

When Francis Williams met Newton, Halley and their colleagues in 1716, they were in the middle of this exhilarating scientific challenge. On the wall of the very room where they met that autumn was framed a grand, engraved illustration, recently composed by Whiston and John Senex, the London maker of maps and globes, showing all 21 known comets, with detailed notes about the attempt to establish their precise orbits. When Newton revised his Principia in 1713, and again in 1726, just before his death, he included new observational data about past comets – and predictions about the future return of some of them. He had proposed a brilliant hypothesis about the way gravity affected even the most seemingly random cosmic objects, and was thus the universe’s guiding force. But it was just a theory. Only the return of Halley’s comet would prove it.

Several fellows of the Royal Society who had been present when Williams was proposed for election later had portraits of themselves painted next to the Principia, to demonstrate their closeness to its author and his brilliant new scientific principles. Martin Folkes posed holding a large folio that probably represented the Principia, with Newton’s bust towering over him for good measure. James Jurin is depicted reading it, Edmond Halley leaning on it. A celebrated late portrait, of which several versions were made, showed Newton seated in his study, surrounded by all the standard pictorial conventions symbolising his distinction as a man of learning – a bookcase full of weighty tomes, a table and a large chair, a celestial globe – and, open in front of him, the third and final edition of the Principia.

One of my earliest discoveries about Francis Williams was that, already as a young man, he collected paintings. He was a connoisseur of art as well as a man of science. As a work of art, his own portrait is not hugely accomplished. But that’s in keeping with the style and quality of most mid-18th-century oil paintings made in the Americas. What’s much more interesting is its composition. First, it was very uncommon in this period for a scholar in his study to be portrayed standing, instead of sitting down. The full-length portrayal of the sitter signified status – it was a mark of prestige. The fact that in this case it was done on a fairly small canvas, whose size would normally have been used for a bust or a half-length, is part of what makes it look odd to our eyes. Second, and more important, I know of no other 18th-century portrait of a scholar that is quite so busy, crammed with intricate, interlocking elements. All those minutiae are clues to its meaning, and to the fact that it was created by a man of unusual ambition and self-possession. This is, without a doubt, Williams’s self-representation. He composed it to convey a particular set of messages about himself.

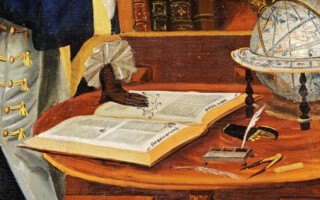

When I first looked at this picture, several years ago, I took in all the details that others had already remarked on. The two fine globes, terrestrial and astronomical, very likely made by Senex; the quills and inkstand; the box of instruments for mathematical drawing and calculation; and the bookcase, in which many of the books have names inscribed on their spines. But three further things also jumped out at me, which seemed to have been overlooked. There was a particular detail about the book on the table. The view through the window appeared to me significant in a way that had gone entirely unnoticed. And then there were Williams’s stockings. Men’s stockinged legs were usually painted completely smooth, even though in reality their silk and cotton bindings were often loose and messy. But Williams’s are curiously wrinkled, presumably painted as they appeared. I couldn’t find another painted example like this. It struck me as a very unusual painterly detail. But it was all just a tantalising puzzle – until I opened the high-resolution scans.

The first thing I did was look closely at the titles and authors on the bookshelves. The letters on the spines are now badly faded and hard to decipher, but they were meant to be clearly legible: indeed, even in 1928, words were visible that have now completely vanished. Nine authors had been identified: Andrea Palladio, the Renaissance architect; Abraham Cowley, the 17th-century poet; Francis Bacon, Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton, the founders of modern science; John Locke, their philosophical counterpart; John Milton, represented by Paradise Lost; William Sherlock, the theologian; and Paul de Rapin, author of the bestselling History of England, published in the 1720s.

Peering at the scans, I was able to make out several more lines: originally, as many as twenty of the spines may have been inscribed. And then, one discovery abruptly transformed my understanding of the whole painting. I had zoomed in on an unidentified volume with a lavishly decorated binding. It’s a big, fat book: that’s one clue. Alongside it, largely hidden behind the curtain, is what looks like an identical volume: that may be another clue. The inscription on the spine is now hard to make out: the V&A’s scientific team read it as ‘COM … ON/DIAR …’ But after several hours of fruitless puzzling over 18th-century authors and titles that might fit that reading, I suddenly noticed that there was, in fact, a tiny third line of text squeezed into the very bottom of the label. This at last unlocked the puzzle and allowed me to read the full title: IOHNSON/DICKTYON/ARY. It is Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary. A huge, very expensive, very prestigious publication. It’s fascinating to know that Williams owned this book – and is here associating himself intellectually with Samuel Johnson, the opponent of slavery and protector of his formerly enslaved Jamaican servant Francis Barber, as well as with Johnson’s great modernising project for the English language. But most important was that Johnson’s Dictionary was published in London on 15 April 1755. For Williams to have a copy on the shelf of his library in Jamaica means that this painting does not date from around 1735 or 1740, as has always been presumed. Instead, it must have been painted towards the end of Williams’s life – between the middle of 1755, the earliest point that the Dictionary could have reached Jamaica, and the summer of 1762, when he died.

Once I had made this breakthrough, other things started to fall into place. First, the redating suggested who painted the picture. The only oil painter known to have been active in Jamaica during these years was an Anglo-American artist called William Williams, who was then in his early thirties. This Williams, the son of an ordinary mariner, had been born in Bristol in 1727. He’d always loved to draw. Sent to sea as a youth, he abandoned his crew in Virginia and spent a few years knocking around the West Indies and Central America, sometimes living among Indians, learning their language and trying his luck as a painter for the local colonists. Eventually, around 1747, he ended up in Philadelphia, where he worked for a theatre, painting sets and backdrops, and in a boatyard, painting ships, as well as doing sign-painting and lettering, teaching music, writing poetry and composing what is now regarded as the first American novel. Though he was entirely self-taught, he also made landscapes and portraits; he collected engravings; he used a camera obscura as a drawing aid; he studied the lives of the great artists and wanted to be one himself. He was the earliest teacher of the young Benjamin West, who later succeeded Joshua Reynolds as president of the Royal Academy and in the 1770s commemorated his old mentor by including his likeness in one of his monumental historical canvases.

William Williams kept a list of every painting he ever made. The original doesn’t survive, but in the 19th century someone jotted down a summary of it. In the spring of 1760, Williams travelled from Philadelphia to Jamaica to offer his services as an artist. His list recorded that during his months in Jamaica, he painted 54 pictures. None of these has ever been found. I am confident that the portrait of Francis Williams is one of them.

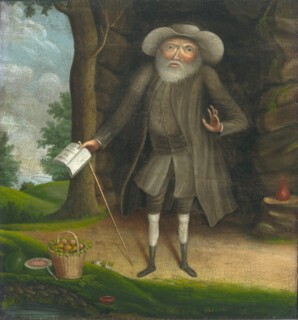

There is in fact a scientific test that could prove this, because it has recently been discovered that William Williams prepared his canvases with a distinctive and very unusual triple layer of underpainting. I’m pressing the V&A to undertake this new test as soon as possible. Meanwhile, the reason for my confidence is stylistic. Williams’s later paintings are increasingly grand and assured in their handling of human figures, though he never fully mastered bodily proportions: his people always remained a bit top-heavy. In a pair of full-length male portraits that he created in Philadelphia in 1766, the handling of the sitters’ hands and bodies is more assured than in the Francis Williams portrait of six years earlier. But there are clear similarities of composition, and probably between 1750 and 1760 William Williams was still finding his way as a competent painter of the human form. This is suggested by the only two earlier portraits known to be by him. The first, made in 1755 but now lost, was a half-length of the most famous Amerindian in the English-speaking world, the Mohawk chief Theyanoguin (also known by his baptismal name, Hendrick), proudly dressed in European clothes. We know what this looked like because it was engraved soon afterwards. So was the second image, painted for Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia, probably in 1758, just before Williams travelled to Jamaica. This canvas, of which two versions survive, was a small full-length portrait of the radical Quaker abolitionist Benjamin Lay. It’s remarkable that William Williams’s first three known paintings celebrated a powerful Native American, an outspoken abolitionist and – if I’m right – a Black Jamaican intellectual.† It’s also notable that his unpublished novel, The Journal of Penrose, excoriated slavery, extolled the equal humanity of ‘negroes’ and white people and included Indigenous, African, Black and mixed-race characters, such as the aged fugitive Quammino, who had fled his long and brutal West Indian enslavement. But when I first looked at his paintings I knew none of this. What immediately struck me instead about the Benjamin Lay and Francis Williams portraits was the great similarity in their handling of the sitters’ legs and feet – and of their stockings. In both cases, these are portrayed in the same untutored but distinctive way: carefully delineated bindings, wound around a pair of spindly legs.

What difference does it make to know that this picture dates from 1760, rather than two or three decades earlier? Quite a lot. It signifies that we are looking at Francis Williams after David Hume’s vicious, racist attack on him in 1753. Williams would have been acutely aware of that intellectual assault: it could not have been more public. The portrait is a rejoinder to it. It demonstrates that its sitter is indeed a ‘man of parts and learning’ – someone of talent and accomplishment in many fields. It was painted just a few months after his poem to George Haldane, with its eloquent arguments about the nobility of Black people and Black minds, and during the period when Williams knew and interacted with Edward Long, a newly arrived young English planter come to seek his fortune in Jamaica.

What is more, the painting represents Francis Williams, himself a planter and slaveowner, at the time of Tacky’s Revolt, the huge uprising of thousands of enslaved people that convulsed Jamaica in 1760. This image was painted while the island was under martial law, and its planters and their free Black Maroon allies were attempting to put down the largest slave rebellion the British Empire had ever seen. There is no trace of this in the painting. No other figures disturb the composition. Through the window everything is calm. But the knowledge of that bloody context reminds us of everything that is omitted from this view, as from any equivalent 18th-century painting – the ‘dark side of the landscape’, in John Barrell’s evocative phrase.

Finally, this is Francis Williams towards the end of his life, in his late sixties. It has always been supposed that by this point he had fallen on hard times and been reduced to living in a rented house in Spanish Town, with only a few possessions. But the portrait disproves that: in 1760 he was rich, confident, unbowed and at the height of his intellectual powers. The redating of the painting completely changes our understanding of the arc of his life and career. On his return to Jamaica in the 1720s, Williams had inherited from his father a large, landed estate, Frog Hall. There is still a dwelling on the spot where Williams’s house must have stood, and where this portrait was almost certainly painted. It’s on a high ridge to the north-west of Spanish Town, with a vast, uninterrupted view of the sky and land beyond. From Frog Hall, you can see all the way to the sea. Spanish Town is plainly visible in the distance. The buildings through the window in the painting surely represent the capital as it then looked.

What does the picture mean? It shows Francis Williams, the scholar of Jamaica, in his study. The objects around him, and the titles of the books on the shelves, testify to the huge, polymathic range of his interests and scholarship – English, Latin, history, medicine, architecture, poetry, theology, philosophy, geography, science, astronomy. If the painting was nothing more than a realistic portrait of an 18th-century Black scholar in his study, that would be extraordinary enough. It’s the earliest such image in Western art, the first self-presentation of a Black person as an intellectual.

But in fact, it is much more than that. It is a very detailed message from Francis Williams, which its original viewers would have immediately recognised. It says not just: ‘This is who I am!’ It also says: ‘Look! This is what happened, and this is what I did!’ This painting commemorates an event, one with huge significance for Williams – and not just for him, but for everyone across the 18th-century Enlightenment world.

The key to understanding that is the book lying on the table in front of him. It is very carefully inscribed with three clues. First, it is labelled ‘Newton’s Philosophy’. Second, Williams’s left hand is resting on a complicated diagram. Finally, the clue that first jumped out at me when I looked at the painting is that the book has a carefully inscribed page number. It is open at page 521. The painter has taken some artistic liberties in order to signify to viewers exactly what this text is. But the page number clinches it. The book is Newton’s Principia – the third and final edition, the only Newtonian text that had a page 521.

That page comes almost at the end of the book, in the culmination of the whole work. So does the diagram, which resembles a particular image at the start of that section (it’s Newton’s Proposition 41, Problems 21 and 22). Those passages concern the hardest mathematical and astronomical problem of all (‘exceedingly difficult’, the text warned), the highest proof of Newton’s theory of gravity and its workings throughout the universe. They are about the way to compute the orbit of a returning, periodic comet – if, as Newton and Halley had theorised, such an event came to pass. There is one more visual clue in the painting. Prominently pointing down at the pages of the book is a tasselled golden cord, arranged in a very unusual knot. It resembles an illustration of the trajectories of comets around the sun.

The reason Francis Williams is drawing our attention to this section of the third edition of the Principia would, I suspect, have been evident to any scientifically literate 18th-century intellectual. It would, for example, have made perfect sense to the scholar Ezra Stiles, who was born in New England in 1727, was friends with Benjamin Franklin, John Winthrop and other important colonial thinkers, and who ended up as president of Yale University. In the 1740s, Stiles had been an undergraduate at Yale, where, as at Oxford, Cambridge and Harvard, astronomy was an important university subject. It involved calculating future astronomical events, including the trajectories of comets. Stiles wasn’t very good at the hardest maths: he was never in Williams’s league. But for the rest of his life, he and his friends remained in thrall to astronomy in general, and comets in particular; in 1751 he even wrote across the Atlantic to the elderly Whiston, soliciting his opinion about the likely return of Halley’s comet. For Stiles, as for Newton, Halley and Whiston, and probably for Williams, comets weren’t just scientifically interesting, but also theologically. What they were made of, and what exactly they did, was mysterious but momentous, part of God’s providential plan for humanity. Many scientists believed, for example, that some comets must have caused the great flood and other extreme and unusual climactic events that were recorded in the Bible; and that other comets had eventually turned into planets.

We know all this about Stiles and his views because of the imbalances of the archive. Because he was part of an enduring family dynasty, held public office, became the head of a university and didn’t live on a hurricane-prone West Indian island – but above all because he was a powerful white man – many of Stiles’s papers have survived, and we can reconstruct a huge amount about his life and outlook. The opposite is true of the surviving archive for Francis Williams, as for any non-white person living in the racialised European slave societies of this era.

In 1771, during his time as a clergyman ministering to white and Black Christians, Stiles sat for a portrait. In his diary he explained that it was the various symbolic details depicted around him, rather than his bodily appearance, that showed who he really was: ‘These Emblems are more descriptive of my Mind, than the effigies of my Face.’ He designed his own picture and told the painter what to draw. What is the first book on the shelves behind Stiles? It’s Newton’s Principia. And what is the curious emblem on the pillar next to him? It signifies, he tells us, ‘the Newtonian system’: that long elliptical shape is the trajectory of a comet.

Throughout the decades of Ezra Stiles’s childhood and early adulthood, the 1730s and 1740s and 1750s, excitement about the return of Halley’s comet built on both sides of the Atlantic, not just among scientists but among the wider public. Its eventual sighting, at the end of 1758 and in the first half of 1759, provoked intense celebration and frenzied activity among scientists across the globe. For the general public, though, the comet proved a rather disappointing sight, even when viewed through a telescope. The great Parisian astronomer Charles Messier described it as ‘a very feeble light, evenly spread out around the … nucleus’. Sometimes its tail was visible, sometimes not. Often it seems to have looked like a very small luminous cloud, or just a blurry shape in the sky. But we don’t really know, because no pictures were painted or engraved recording its actual appearance. Instead, observers across the world recorded its passage in numerical calculations, by drawing lines on charts, and by describing it in words.

In all the Americas, only John Winthrop at Harvard seems to have been expert enough not only to observe Halley’s comet systematically, but also to compute and fully understand the significance of its trajectory through the skies. Stiles filled page after page with observations, calculations and diagrams, but his grasp of the underlying principles was much less solid. Further south, over the Caribbean, the comet was clearly discernible for several weeks. As it approached Earth, it was often visible with the naked eye from the early evening onwards. In Barbados, the colonist Thomas Stevenson observed it and wrote to the Astronomer Royal in London arguing that Halley and Newton’s theory was wrong. (It wasn’t.) In the west of Jamaica, Thomas Thistlewood twice noted its passage in his diary, without much detail. Near Black River Bay on the south coast, the doctor and naturalist Patrick Browne more carefully recorded the comet’s position in the sky over several days and sent his data to a newspaper in London, though without seeming to understand why its location was changing and what that signified. In fact, as both entities hurtled through space on their separate trajectories, Halley’s comet had achieved its perigee, its closest approach to the Earth, during the hours between 25 and 27 April 1759. At dusk on that last day, low in the sky over Spanish Town, it had aligned with two important constellations that were discernible below it: the stars of Centaurus and of the Southern Cross.

By this time, Newton, Halley and Whiston were long dead. So was Martin Folkes, who had proposed Francis Williams for election to the Royal Society when they were both young men and had himself later become its president. Not many people were still alive who had known and discussed the cutting-edge mathematics of comets with those great luminaries, decades ago. Almost certainly no one outside Europe.

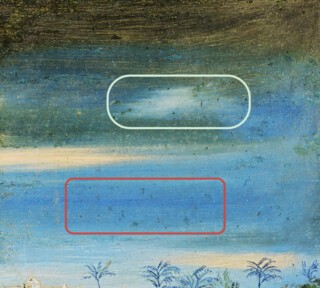

Except Francis Williams. Look again at the window behind him in his portrait. Through it, you can see palm trees, a river, thatched colonial buildings. The light coming through the window is bright – it is casting shadows on Williams’s legs and furniture. This is the final clue that jumped out at me when I first looked at the picture, though it took me years to figure out its exact significance: it is not daytime. That bright light is not coming directly from the sun. The top of the sky is pitch black. There are tiny yellow points of starlight in the distant firmament. It is night-time. More precisely, it is dusk – an excellent time to observe Halley’s comet during its passage over Jamaica, and its nearest approach to Earth, in late April 1759. In the middle of the sky is a curious arrangement of darkish painted asterisks in a roughly oval formation. It’s supposed to stand out: in the earliest photographs of the painting, taken a century ago, it shows up even more clearly than it does now. It looks like a pattern of stars. That is how astronomers computed the trajectory of comets: by alignment with particular constellations. Page 521 of the Principia is about plotting the changing latitude and longitude of a returning, periodic comet by reference to the fixed stars around it. It is part of Problem 22, the Principia’s ultimate, incredibly taxing observational and mathematical puzzle: how to correct the computation of a comet’s parabolic trajectory for the motion of the Earth, allowing for the difference in plane between the planet’s own orbit and that of the passing comet – a further refinement of the already ‘exceedingly difficult’ Problem 21. In this final case, Newton says, you must start by determining, ‘by very accurate observations’, the exact location of the comet at its perigee.

Immediately above that starry formation in the atmosphere is a small, furry white blob. You could easily miss it. For the past century, no one has noticed it. But more than 250 years ago, it was deliberately placed in that exact location. We can see that on the infrared scans of the picture. When William Williams made his first pencilled marks on this canvas, to plot the composition, he carefully ruled a series of lines to show where that white object in the sky should go – and to mark its relation to the constellations he was told to paint below. His sitter made sure of that, as he made sure of every other carefully placed detail in his portrait.

The portrait of Francis Williams is the only painting ever made of Halley’s comet in 1759, on its momentous first predicted return. This is the occasion that this object commemorates. It was an event with huge significance for Williams – and for every other intellectual across the Enlightenment world. It marked the triumph of Newtonian science, of a new, rational scientific and religious outlook. A triumph of British scientists. A triumph of scholars from Cambridge. To all those overlapping, Enlightened worlds, Williams’s painting conveys a proud visual message:

I, Francis Williams, free Black gentleman and scholar, born in Jamaica and educated in Britain, witnessed the return of Halley’s comet – and I calculated its exact trajectory, according to the rules of the third edition of Isaac Newton’s Principia.

On the table, dipped in ink, are the mathematical instruments with which he has done this; behind him is the comet. It is a work of breathtaking intellectual poise and self-confidence.

Edward Long almost certainly knew the meaning of this picture. He was in Jamaica in 1759 and 1760. He would have seen Halley’s comet, and known about the visit of the painter, William Williams, the following year. He interacted with Francis Williams at exactly this time. Long was a well-connected and powerful young man: a judge, an assembly man, a published author, the brother-in-law of the lieutenant-governor. But in 1760, Williams was older and possibly richer than Long. Better educated. Cleverer. Proud of himself. Perhaps he was condescending towards Long, who had never been to university or learned sophisticated mathematics. And so, after Williams’s death, and his own return to England in 1768, Long suppressed the facts, hid the painting away, and helped instead to create the malicious fable that Africans and other Black people were intellectually backwards, especially when it came to science. That became a terribly powerful myth, the legacy of which we are still wrestling with. As far as I know, the Royal Society did not elect a Black fellow until 2023.

This picture proves the opposite. It shows a Black person, born to enslaved African parents, who already as a youth was mathematically talented enough to understand the most complicated, avant-garde science in the world. As a young man he engaged, as a fellow-scientist, with the brilliant creators of the new, Newtonian principles of the Enlightenment. At the end of his life, aged almost seventy, he celebrated that they had been proved right, and associated himself with that achievement – the greatest revolution in science before the 20th century. It’s a miracle that this painting survives. Everything about it is extraordinary. But so was the man who commissioned, designed and bequeathed it to posterity.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.