My first visit to the British Museum was on a date, and under duress. My objection wasn’t to elite cultural institutions or stolen goods, but to visiting a museum about Britain. I was studying classics to get away from all that. I can still remember the bewilderment of walking into those first long galleries with their five-legged bulls and giant stone kings. I saw the Rosetta Stone and burst into tears. It had never occurred to me that such things existed in a visible world beyond my books, or that places so far away really existed at all. I got that feeling again at the Silk Roads exhibition (until 23 February).

The most exquisite object in the show is also the simplest: a glass bowl tinted Strega yellow, not much larger than your cupped hand, with its sides cut down to hexagonal facets that intersect in a honeycomb pattern. Made in Iran in the sixth century ce, it was dedicated two centuries later by the Empress Kōmyō in the imperial treasury of Heijō-kyō, the capital of Nara Japan, 7500 km to the east. It isn’t clear how the bowl reached the Japanese court – via an envoy, perhaps, or a monk – but it almost certainly came by way of China, then ruled by the Tang dynasty.

The history of the glass bowl illustrates the twin themes of this astonishing show, the best I’ve seen at the museum in the last thirty years: the vast distances travelled by objects and ideas, and the local and regional circuits in which they moved. Right away it upsets the usual story – these Silk Roads led east from China. The exhibition starts with journeyways between China, Japan and Silla, a ‘kingdom of gold’ that united most of Korea in the seventh century and became an empire with Chinese characteristics, including Chinese script and the Chinese education system. The state academy that opened in the capital, Geumseong, in 682 was modelled on the Imperial Academy.

From there the displays snake west across the dark space of the gallery, evoking a journey made by starlight in cool desert air. The plinths and showcases vary in height to reflect the terrain and to avoid blocking views down the length of the gallery, connecting the lands of six broad regions. The names of cities hang from above in grey block letters like a dim Milky Way.

The focus is on the period from 500 to 1000 ce, traditionally Europe’s Dark Ages, and for the most part the regional sections explore overland routes, with appended case studies devoted to maritime connections. In the first, a ninth-century shipwreck discovered in 1998 off the island of Belitung near Sumatra demonstrates the complexity of transoceanic links. The vessel was on its return trip west from China when it sank, heading for the trading cities of the Abbasid caliphate (a journey contemporary Arabic accounts suggest could take around six months), but it seems to have diverted from the standard route through the Strait of Malacca to call at an Indonesian port, or perhaps even directly at the spice islands another thousand kilometres east. Whatever the ship was doing in these dangerous seas, its contents reveal a massive commercial operation at work. If the Silk Roads of the popular imagination are named for a light and costly fabric ideal for overland transportation, the weightier maritime equivalent was china itself: porcelain made of finer-grained clays than those found further west, which were then fired at higher temperatures to produce a stronger, whiter and even translucent effect. The merchants may have spent a year or more at a Chinese port acquiring their cargo: almost sixty thousand separate items made in Hunan province were recovered, more than 90 per cent of them painted and decorated bowls piled up and protected by straw, or layered in stacked circles within larger vessels. Bowls weren’t popular local products of the Changsha kilns, so these must have been a special order for shipment west.

The only overland routes from China to Central Asia ran through the Hexi corridor between Mongolia and Tibet to the Tarim Basin, where they continued north and south of the Taklamakan desert. Another showstopper, a plain bolt of silk made in the third or fourth century, was excavated at Loulan in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in the far north-west of modern China. It has a bracing functionality, but it is also fragile: a creased, flattened cylinder, yellow-brown and broken in two. Standard bolts of 12m x 54cm were used for tax payments in Tang China. On routes west they could serve as salary for Chinese soldiers, and as valuable currency.

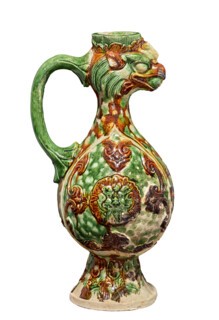

It wasn’t only silk, of course. Lightweight luxuries of all descriptions came through this region. The forests of Tibet supplied musk, made from the glands of the male musk deer. Visitors to the exhibition can smell this aroma (something like polished furniture), along with incense and balsam, from ‘scent boxes’, an alternative to the usual games and dressing-up chests. Scents, salt and Central Asian wine travelled east towards China. There, as often, exotic goods were prized more for looks than function. Incense burners were a necessary technological upgrade to make anything of the new aromatics, but wine could be enjoyed without specialised equipment, and barware from the west was at first a curiosity: imported drinking horns inspired local copies without spouts, while a dramatic porcelain jug fashioned in the form of a phoenix preserves the shape of a West Asian wine ewer, but there is no hole in the bird’s beak for the liquid to pour out. The conquest of distance has a power of its own: more than half of the items on display come from the British Museum’s own collections.

Traffic was heavy along these remote paths. One of the first stops on the southern branch was the town of Dunhuang, near a Buddhist temple complex built in the Mogao caves. In 1900, a ‘Library Cave’ was uncovered, with treasures including more than seventy thousand manuscripts in almost twenty different languages, from Chinese and Tibetan to Sanskrit and Old Uyghur. Some are bilingual, with necessary amendments: Buddhist texts in Sanskrit written vertically, for instance, to map onto Chinese characters alongside. Others are phrasebooks: a manual for Tibetan travellers supplies useful Chinese terms in Tibetan script, beginning with ‘chopsticks’ and ‘beer’ (which in Chinese becomes ‘barley wine’) and ending with ‘Be quiet!’

Buddhism had reached Chinese cities from India in the first or second century ce and spread from there to Korea and Japan. It was entirely compatible with commerce, including in human beings: documents record the involvement in the slave trade of monks and nuns in the Tarim Basin. The silkworms fared better: unlike in China, the silk producers of Buddhist Khotan on the southern route round the Taklamakan practised a no-kill method, allowing the larvae to hatch as moths before harvesting their fabric cocoons.

North of the arid desert the rulers of the Uyghur kingdom of Kocho adopted a different Asian religion from China. In the third century ce, a Mesopotamian prophet called Mani had invented a new form of Christianity that incorporated aspects of Judaism, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism and Mithraism. It was based on the dualism of light and dark, good and evil, God and matter, and it focused on the possibility of redemption, though of a rather gradual kind: only a limited number of ‘Elect’ could achieve an end to the wandering of their souls at the end of their lives, and only if they rejected worldly possessions and concerns and became vegetarians. The best the larger class of ‘Hearers’ could hope for was to be reborn as members of the Elect. Manicheanism survived in China until the 14th century, and travelled west as far as Rome. Its shadow would hang over Western Christianity for more than a millennium, calling into question the orthodoxy of Catholic sects including the Bogomils and Cathars.

Our journey continues past emotional camels and a well-preserved ancient jam tart. At the heart of the Silk Roads were the Sogdians, traders who lived in Central Asian cities between the Oxus and Jaxartes in modern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, spoke a form of Persian that still survives in Tajikistan, and travelled between Iran, India, Siberia and China. They made an impression there: an octagonal gold cup from the Yangzhou region, found on the Belitung wreck, depicts seven Central Asian musicians and a dancer with his arms and one leg in the air. This is a spinning dance or ‘Sogdian whirl’ that had become very popular among the Chinese, who called it the huteng wu (‘foreign leaping dance’). At the same time, the Sogdians’ Aramaic script was adopted by Uyghurs to the east, and later inspired the Mongolian and Manchu writing systems.

At home the Sogdian city-states thrived under the nominal suzerainty of semi-nomadic Altaic-speaking Türks to the north, who used their urban centres for trade and took a share of their profits. When the Türks fell to the Tang in the seventh century, Sogdians made common cause with China. This is the era that produced the centrepiece of the Sogdian case study: a painting in jewel colours of almost unearthly intensity that once covered the southern wall of a reception room in an aristocratic house in Samarkand, the leading Sogdian city-state. A loan from Uzbekistan’s Samarkand State Museum-Reserve, it depicts the ritual procession King Varkhuman makes to a shrine where he will sacrifice to his ancestors in honour of Nowruz, the spring equinox festival that marks the Iranian New Year. His train includes soldiers, wives (the most favoured riding an elephant) and Zoroastrian priests wearing mouth coverings to avoid polluting the sacred fire altars which they tended.

Further west there is a greater choice of routes. They lead us through the Red Sea, the Mediterranean, the Sahara, and along the Austrvegr or ‘Eastern Way’ that travelled from Baghdad and Constantinople down the Volga and the Don to the Baltic, bringing silk to the graves of Vikings (here relabelled Scandinavians, though #notallScandinavians). Islamic silver came too, with Asian balances to weigh it out. The main trade along these routes was again in human beings: one display case juxtaposes an iron restraining collar found in Birka in Sweden with a fine silver neck ring from Estonia, no doubt forged from the proceeds of the slave trade.

Buddhism made no significant inroads west of India, where the rise of Islam didn’t help its chances, though the impact of the Buddhist monastic tradition on early Christian institutions in Egypt and then Western Europe is still an open question. The story of the Buddha himself fared better. Originating in India, it is first found in texts written by Manichaeans in Uyghur and Persian in the Tarim Basin. It was translated into Arabic as the tale of Bilawhar and Būdhāsaf, and from there into Georgian as The Life of the Blessed Iodasap, a Christianised story of an intolerant Indian king and the hermit, Barlaam, who converts the crown prince to Christianity despite his father’s threats and the efforts of various evil spirits. In the 11th century, it was translated into Greek by a Georgian abbot (the stage represented here, with an attractively illustrated manuscript), and then Latin and Old French; by the 13th century it could be found in Iceland in Old Norse. In medieval Europe the story was known as ‘Barlaam and Josaphat’ – the latter a corruption through multiple translations of Bodhisattva, the ‘future Buddha’ born Prince Siddhartha – and ‘Saint’ Josaphat got his own Christian feast day.

The exhibition ends in these western lands, a canny strategy for keeping the attention of visitors as they move towards the better known: it’s the first time I’ve seen a show at the British Museum where the queue didn’t scatter at some point along the route as people got restless and sped up. Their reward is a single object in a final spotlit case: a sturdy whalebone casket made in a Northumbrian monastery around 700 ce, carved around with vivid cartoons of Roman, Norse, Jewish and Christian stories, and dedicated in runes in Old English to the whale.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.