The collection of modernist art from Ukraine currently on show at the Royal Academy is both an exhibition and a conservation project. In the Eye of the Storm (until 13 October) comprises 65 pieces, most of them on loan from the National Art Museum of Ukraine in Kyiv. After the removal of works from Kherson Art Museum at the beginning of Russia’s invasion (ten thousand pieces are missing and have reportedly been taken to Crimea) and Mariupol’s Museum of Local Lore (there are Russian plans to build a ‘liberation museum’ in the city), a travelling exhibition was organised to get some of Ukraine’s most important remaining artworks out of the country. Zelensky’s office arranged a military escort to Poland. The paintings left Kyiv on 15 November 2022 under heavy shelling. Their arrival at the border coincided with a stray missile exploding on Polish territory.

The exhibition covers the period from 1909 to 1932, when Ukraine went through a series of political transitions, from tsarist rule to the national revolution and the establishment of a short-lived independent Ukrainian state, the War of Independence and the subsequent creation of Soviet Ukraine in 1922. The tumultuous period of independence from 1918 to 1921 saw the establishment of new cultural institutions: the revolutionary government founded the Ukrainian Academy of Art – Ukraine’s first higher arts institution – and the Kultur Lige, an organisation dedicated to contemporary Yiddish culture. In the 1920s, the Soviet authorities introduced an indigenisation programme to foster national varieties of socialism. This endorsement of artistic freedom and local specificity did not last long. The exhibition concludes with the Stalinist crackdowns of the 1930s, which resulted in the execution or suppression of many Ukrainian artists, and the imposition of Socialist Realism as the only acceptable artistic style.

The exhibition’s aims are twofold: to introduce audiences unfamiliar with this history to the great diversity of artists working in Kyiv, Kharkiv and Odesa during the first decades of the 20th century, and to challenge ‘Russo-centric’ art historical interpretations, which have traditionally categorised them as part of an extended Russian avant-garde. In the first it succeeds – there are examples of Constructivist typography, abstract and figurative painting, avant-garde costume design – but the second is more complicated. Many of the artists on display at the RA had connections across the Russian Empire and Europe. Most of the names appear in their transliterated Ukrainian spellings (including ‘Kazymyr Malevych’), a decision the curators justify as in keeping with their attempt to reframe this history.

The Cubo-Futurist painter Alexandra Exter is representative of the cosmopolitanism of the period. She was born in 1882 in Białystok, now in Poland but then part of the Russian Empire. Her family moved to Kyiv when she was three and as a young woman she studied at the newly established Kyiv Art School, leaving after graduation in 1906 for Paris and the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. Here she met Fernand Léger, who became an important friend and supporter, though she was criticised for her bold palette (criticism she didn’t take to heart).

Exter once told a sceptical Léger that colour was the ‘Eastern’ contribution to Cubism. There is certainly an abundance of it in the opening rooms at the RA. The Caucasus landscapes of Alexander Bogomazov, a classmate of Exter’s in Kyiv, are one of the surprises of the exhibition, with their rolling scrolls of fuchsia and royal blue hills and mountains. Bogomazov admired Gauguin’s Polynesian pictures, which he saw in Moscow in 1911, though his own landscapes are more dramatic in tone, with brighter whites, large areas of dark blue and very little green.

The exhibition also includes works by Sonia Delaunay, who was born Sara Stern to Jewish parents in Odesa in 1885. Orphaned at the age of five, she was sent to live with her aunt and uncle in St Petersburg and later studied art in Germany and then in Paris. She shared Exter’s interest in vivid colour (the two women met in Paris in 1911), and with her husband, Robert Delaunay, developed a technique they called Simultanism, in which contrasting colours are placed alongside each other, or allowed to overlap, creating an impression of motion and gesture. Exter’s Composition (Genoa) of 1912 is displayed next to Delaunay’s Simultaneous Contrasts (1913). Both are composed of abstract forms, but follow different chromatic patterns. In Exter’s painting, a hazy cityscape is conjured from chunks of colour that shade into one another. A soft sweep of curves in paler colours carves a space through the centre of the canvas – a street or a river perhaps – while darker curves rise towards a central arch. Delaunay’s painting is made up of cleaner geometric shapes: her marks are sharp where Exter’s are loose, and the effect of her interlocking colours is flatter but more rhythmic. In the gallery text, the curators suggest that such use of colour was influenced by local folk traditions, though no examples are given of the folk art in question.

On this point the catalogue is more instructive, though it doesn’t bear out the colour assertion. Both Exter and Delaunay experimented with textiles and embroidery: Exter took a particular interest in local crafts before her introduction to Cubo-Futurism in Paris. In 1914, she became artistic director of the Verbivka embroidery studio near Kyiv, where, with the help of the Kyiv Handicraft Society, she put together an exhibition of textiles, Contemporary Decorative Art, which showed in Moscow in November 1915. It was made up of 214 works of embroidery by folk artists (‘peasant-futurists’ as Exter called them) from Verbivka and another co-operative, near Poltava, based on sketches and designs by avant-garde artists including Malevich.

Malevich, who is represented in the show by a handful of works, was born in 1879 to Polish parents who had settled near Kyiv. As a young man, he found rural labourers more intriguing than their urban counterparts, who ‘never drew … nor were they capable of decorating their houses, in contrast with the peasants who all were. Country people were interested in art (a word I did not then know).’ This habitual decoration was, he wrote in his autobiography, ‘the background against which the feeling for art and artistry developed within me’. Exter’s textiles show predated by a month the first public exhibition of Malevich’s 39 Suprematist paintings, leading one of the RA curators, Katia Denysova, to suggest that ‘Suprematism first appeared in public not on canvases but as needlework.’ It does seem significant that Malevich chose to inaugurate Suprematism at an exhibition of decorative art – an early testing ground for his belief in the extra-artistic applications of his new forms.

Not all the artists represented here moved towards abstraction and non-academic experimentation. One of the virtues of the exhibition is its breadth, taking in many of the artistic movements that flourished in the early days of Soviet Ukraine. The Boichukists (named after their founder, Mykhailo Boichuk) were among the beneficiaries of indigenisation, painting state-commissioned murals in opera houses and sanatoriums. Their scenes of peasant life drew on Byzantine iconography, which they considered part of Ukraine’s artistic heritage. In 1937 Boichuk, along with his wife and two of his followers, were executed in the Stalinist purges, their depictions of rural work having become evidence of what was considered a dangerous (and specifically Ukrainian) ‘bourgeois nationalism’. The murals were whitewashed, but even the smaller temperas that survive retain an air of being public works, with their solemn, composed figures looking out to meet our gaze.

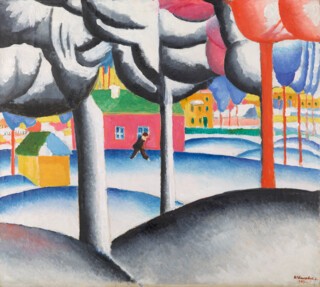

Malevich, who worked with Boichuk at the Kyiv Art Institute, didn’t approve of the murals, believing that a tradition with its roots in monasticism had no place in a proletarian state. He began teaching in Kyiv in 1928 after the State Institute of Artistic Culture in Leningrad was forced to close. It was around this time that he returned to figuration, painting a startling series of faceless peasants looming over patterned fields. None of these works is on display at the RA, but we do get Landscape (Winter), which shares those paintings’ rounded lines and brilliant shading. The turn to figuration has sometimes been explained as an attempt by Malevich to placate a Soviet government increasingly hostile to abstraction. But if that was the case, Landscape (Winter) is a work of misdirection. There’s something sinister about its prettified brightness, a sense that the landscape is trying to masquerade as something it isn’t. Perhaps this is why the season needs to be identified in parentheses. Other elements contribute to the air of disquiet: a tree in the foreground is missing one of its grey lobes and Malevich has set the main picture plane behind the trees, so that we seem to spy out on the man striding across the scene.

During the 1930s, many of the works on display at the RA became part of the spetsfond, a secret cache of art by ‘public enemies’ held in the basement of the State Ukrainian Museum. In the 1950s, the archive was separated into categories in order of public merit. Almost all the spetsfond pieces were deemed ‘Category V’, works of ‘low ideological and professional quality’. These pieces, subsequently referred to as ‘zero-category’ works, were taken out of their frames and rolled up. They weren’t looked after but neither were they destroyed. Forgotten in the basement, they remained there undisturbed, overlooked, waiting to be retrieved.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.