After two hours on the tarmac at LaGuardia Airport, the flight was cancelled and we were deplaned. I had been seated next to a former congresswoman who lost to another incumbent in 2022 as a result of redistricting, after decades in the House of Representatives. Like me, she was on her way to Chicago to attend the Democratic National Convention. The next morning she was due to have breakfast with Nancy Pelosi, the former speaker of the House, and in the afternoon there was a tea for the Equal Rights Amendment prohibiting discrimination ‘on account of sex’, first proposed in 1922 and ratified by the required 38 states as of 2020, but still not officially part of the constitution because of legal and procedural obstacles relating to a time limit set by Congress in the 1970s for the amendment’s ratification. With the Supreme Court now tilting right and reproductive rights being curtailed in many states, getting the amendment in the constitution was more important than ever, she told me. Most other liberal democracies had constitutional provisions of this sort, ‘even Japan’. She didn’t mention it, but it was the 104th anniversary of the day American women won the right to vote, with the ratification of the 19th Amendment in Tennessee. I was planning to attend a party that evening thrown by the Nation for Jesse Jackson. It was not to be. We waited on standby at the airport late into the evening. The former congresswoman chastised me for being insufficiently read in the works of Robert Caro. We watched each other’s bags in the line to be re-ticketed and I tried to help her with the airline app on her phone. ‘I used to chair committees and have an entire staff to do these things for me,’ she said. The last flight to Chicago left without us and we went our separate ways. I caught an afternoon flight the next day.

With an extra night to myself before the convention, I returned to the literature of Kamala Harris. Her memoir, The Truths We Hold (2019) – an awkward title, the salience of the line from the Declaration of Independence being that the truths are self-evident, not the holding of them – is a campaign book, written in collaboration with a pair of Washington speechwriters, Vinca LaFleur and Dylan Loewe (‘You made this process a joy,’ Harris tells them in the acknowledgments). It makes for dreary reading (‘This is where I learned that “faith” is a verb,’ Harris writes about attending church as a child and hearing Christ’s injunctions to help the poor. ‘I believe we must live our faith and show faith in action,’ and so on) but it served as the blueprint for the biographical elements of the convention programme. There is the journey of Shyamala Gopalan from New Delhi to Berkeley in 1958, aged nineteen, ‘to pursue a doctorate in nutrition and endocrinology, on her way to becoming a breast cancer researcher’; the love story of Shyamala and Donald Harris, a graduate student in economics, ‘while participating in the civil rights movement’ and despite her family’s expectations that she return to India and an arranged marriage; the birth of Kamala and her sister, Maya; the marches they went on with their parents, where Kamala first spoke her favourite word, ‘fweedom’; Shyamala and Donald’s divorce after the family spent a few years in the Midwest; the move back to Berkeley, and riding the bus to school as ‘part of a national experiment in desegregation, with working-class black children from the flatlands being bused in one direction and wealthier white children from the Berkeley hills bused in the other’; the move to Montreal in middle school when her mother was hired at McGill; her decision to return to the US to attend Howard University and become a lawyer (‘I cared a lot about fairness and I saw the law as a tool that can help make things fair’); and, of course, Aretha, Miles and Coltrane on the stereo.

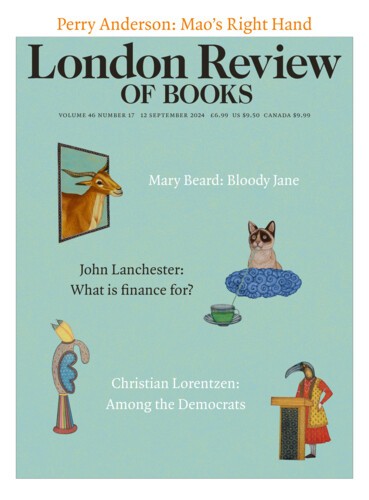

The convention leaned heavily on biography and family, a mix of relatability, struggle and aspiration. It had the feeling of a party thrown for the departing grandparents by the aunts and uncles, with an audience of cheering grandchildren. The Democrats have learned the lessons of 2016: no more will Donald Trump’s supporters be tarred as racist, sexist, homophobic or otherwise ‘deplorable’. Instead, the opponents were Trump ‘and his allies’ or Trump and his ‘billionaire allies’, who are ‘weird’, selfish, narcissistic, tortured by their own inadequacies, ‘lapdogs for the billionaire class who only serve themselves’. For the most part Trump wasn’t framed as an existential threat to democracy, as he was in the campaign playbook Biden was following until he exited the race. Instead, he was belittled as a ‘small man’, ‘not a serious man’, a ‘two-bit union buster’, a ‘scab’, a ‘bad ex-boyfriend’. Trump’s ideological destruction of the bond between the conservative movement and the Republican Party – previously united under the tripartite imperatives of free enterprise, Christianity and a strong military – and his transformation of the GOP into a personality cult with an atmosphere of white grievance and nativism have allowed the Democrats to open their tent to all-comers, from neocons to the self-proclaimed socialist left. It is now the party of labour and of capital; the party of debtors and of bankers; the party that mocks the Ivy League but is largely run by Ivy Leaguers; the party of anti-monopolists and of Silicon Valley; the party for immigrants and for border security; the party of insiders and of the marginalised; the party of the football team and of the sorority; the party of family and of freedom; the party of ceasefires and of the war machine; the party that opposes fascism but abets a genocide. In Chicago, we were constantly reminded that it was the party of joy, whatever that means.

And the convention was definitely a party. The lines to get in were long and slow, and the enthusiasm inside was very real. I have attended four previous political conventions and I have never witnessed a crowd so much in love with politicians or so ecstatic about expressing it. All such gatherings have a showbiz element, but the Democrats seemed to have borrowed from Trump and had amped up the musical numbers, bringing in fairly decent if not uncorny talent, from Stevie Wonder on down. I finally arrived at the United Center on Monday evening, too late to see the pro-Palestinian march that breached ramparts and led to thirteen arrests, but in time to hear Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez recounting her journey from taking omelette orders in Manhattan six years ago, with her family facing the loss of their home after her father’s death from cancer, to political stardom. She had been preceded by Shawn Fain, president of United Auto Workers, and between them the interchangeability of ‘working class’, ‘middle class’ and ‘everyday Americans’ in current Democratic vocabulary was made clear. That Ocasio-Cortez was granted a primetime slot signalled the alliance forged under Joe Biden between the party’s centrist establishment and its formerly insurgent left wing.

The uneasiness of that alliance became clear the next night when Bernie Sanders asserted that ‘billionaires in both parties should not be able to buy elections, including primary elections.’ It was a reference to his thwarted 2016 challenge to Hillary Clinton, but also to the recent defeat of two left-leaning congressional incumbents, Jamaal Bowman and Cori Bush, who had spoken out against Israel’s war in Gaza, to candidates funded by AIPAC (the American Israel Public Affairs Committee). Sanders was followed by J.B. Pritzker, governor of Illinois and son of the president of Hyatt Hotels. ‘Donald Trump thinks that we should trust him on the economy,’ Pritzker said, ‘because he claims to be very rich. But take it from an actual billionaire, Trump is rich in only one thing: stupidity!’ The applause from the hometown audience was overwhelming – it wasn’t a tough crowd – and the woman to my right, who had spent Sanders’s speech discussing Taylor Swift with the woman on her other side, gushed: ‘He’s such a badass!’ The juxtaposition showed that the Democratic tent is big enough for firebrands who denounce billionaires as well as the right sort of billionaire. Ocasio-Cortez and Sanders delivered two of the strongest calls for ceasefire in Gaza, with Sanders describing the war as ‘horrific’. He repeated his call for the US to ‘guarantee healthcare to all people as a human right, not a privilege’, a stance Harris held while campaigning for the presidential nomination in 2019, but which is no longer part of her programme.

The first night of the convention culminated with the fond exorcism of the party’s defeated or potentially defeated old guard. Hillary Clinton gave a speech about mothers. She recalled her own mother, Dorothy, who was born in Chicago before women had the right to vote. She referred to the anniversary of the previous day: the mother of a Tennessee lawmaker, ‘a widow who read three newspapers a day’, had, she said, swung the decision by telling her son, ‘No more delays. Give us the vote.’ She recalled Shirley Chisholm’s 1972 candidacy for president, Geraldine Ferraro’s selection as Walter Mondale’s running mate in 1984 and her own nomination in 2016. The 2016 convention in Philadelphia ended with images of a shattered glass ceiling, a victory declared too soon. Jubilant as the convention in Chicago was, the party is more circumspect now. The emphasis was less on historic firsts and more on the need to secure reproductive rights in the face of a Republican Party that would seek to ban abortion nationwide (as it has been banned in fourteen states since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade) and curtail access to fertility treatment. Clinton pointed out that both she and Harris had started their careers as lawyers representing children and young women who were victims of sexual abuse. The point was driven home by the stories of Hadley Duvall, a Kentucky woman who testified to being raped by her stepfather, and Wanda Kagan, a high-school friend of Harris’s who was taken in by Harris’s family after they found out that Kagan’s stepfather was abusing her. The paranoid fantasists of the right like to frame the Democrats as child traffickers (see Pizzagate), but the Democrats convincingly portrayed the Republicans as enablers of actual child rape. The Democrats are now trying to enshrine abortion rights, especially at state level, through legislation, but restoring Roe or something like it will depend on future appointments to the Supreme Court. Three right-leaning justices are 69 years old or older (Clarence Thomas is 76) and left-leaning Sonia Sotomayor is 70.

For a former secretary of state, Clinton’s remarks were light on foreign policy. The convention as a whole was light on foreign policy, which was generally alluded to in terms of ‘strengthening our alliances’ or ‘advancing our security and values abroad’ and, of course, ‘honouring our troops’. Actual US policies and interventions weren’t much mentioned, nor were Benjamin Netanyahu, Xi Jinping or Vladimir Putin. ‘I can tell you,’ Clinton said, ‘as commander-in-chief Kamala won’t disrespect our military and our veterans. She reveres our Medal of Honor recipients. She won’t be sending love letters to dictators.’ She smiled and basked in the irony of chants of ‘Lock him up!’ as she taunted Trump for falling ‘asleep at his own trial’ – an instance of the new politics of joy converging with the opposition’s politics of revenge. Before exiting to her 2016 campaign theme, ‘Fight Song’, Clinton declared: ‘We have him on the run now.’

That might not have been the case had Biden elected to continue his campaign for re-election, a sacrifice Bill Clinton two nights later compared to George Washington choosing not to stand for a third term (it was the baby boomers who provided the week’s historical trivia). To cries of ‘We love Joe!’ and ‘Thank you, Joe!’, Biden talked about his motivations for running in 2020: in Charlottesville in 2017 ‘Neo-Nazis, white supremacists and the Ku Klux Klan’ were ‘so emboldened by a president they saw as an ally, they didn’t even bother to wear their hoods. Hate was on the march in America.’ It was a return to the playbook of his abandoned campaign: democracy under threat, the US as ‘Germany in the early 1930s’. He had built up a foe too big and awful for him to beat in his old age, and now he was ready to joke about it. ‘I know more foreign leaders by their first names and know them as well as anybody alive, just because I’m so damn old,’ he said. ‘I’ve either been too young to be in the Senate because I wasn’t thirty yet or too old to stay as president.’ The list of his achievements in office was lengthy: insulin prices capped at $35 a month; ‘Covid no longer controls our lives’; record highs for the stock market and 401(k)s (a kind of savings plan); roads and bridges modernised; lead pipes removed from schools; a modicum of student debt relieved; 800,000 new manufacturing jobs; the first black woman on the Supreme Court.

As for Gaza, Biden said:

We’re working around the clock … to prevent a wider war and reunite hostages with their families and surge humanitarian health and food assistance into Gaza now to prevent the civilian suffering of the Palestinian people and finally, finally, finally deliver a ceasefire and end this war. Those protesters out in the street, they have a point. A lot of innocent people are being killed on both sides.

The protesters were also in the building. Outside my sightline and probably outside his, a group of delegates unfurled a banner reading ‘STOP ARMING ISRAEL’ in red, green and black. They were quickly blocked by fellow delegates holding ‘WE 🖤 JOE’ signs. On the way out of the United Center I heard a pair of Democrats lamenting that this had happened. ‘Well, at least they stopped it quickly,’ one said. ‘Doesn’t matter,’ the other said. ‘It’s the pictures that matter.’

The convention was an exercise in celebrity creation. Harris has been on the national stage for years but in a subordinate role, dispatched most often to speak to the liberal choir on friendly talk shows and at rallies for reproductive rights. She hasn’t figured as an object of hate for the right-wing media on the scale of Ocasio-Cortez, let alone Hillary Clinton. Dan Morain’s 2021 biography, Kamala’s Way, reissued in 2022 with a new epilogue, charts Harris’s rise in San Francisco politics. Morain is a veteran reporter for the Los Angeles Times and the Sacramento Bee. He recalls a conversation with the San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen:

Caen told me one of the secrets of his success: San Francisco was a town without celebrities, so he had to create them. It’s one way his three-dot column became a must-read for San Franciscans for fifty years. He defined the city, was its champion, its scold, its arbiter of class and the classless. And no one played a bigger part in the world he chronicled than his good friend Willie Brown.

Brown was the speaker at the California State Assembly for decades, until term limits were imposed in the early 1990s. Near the end of his tenure, he started dating a young prosecutor in the Alameda County district attorney’s office. She made her first appearance in Caen’s Chronicle column in an account of Brown’s birthday in 1994. ‘Caen reported,’ Morain writes, ‘that Barbra Streisand was at Brown’s sixtieth and that Clint Eastwood “spilled champagne on the speaker’s new steady, Kamala Harris”.’

According to Morain, ‘Brown gave Harris a BMW … she travelled with him to Paris, attended the Academy Awards with him and was part of the entourage’ that went with him to the East Coast, where among other business, he met with Donald Trump, who wanted to discuss a potential hotel project in Los Angeles. Harris rode with Brown on Trump’s private jet from Boston to New York but ‘likely’ didn’t meet him. Morain’s point is that Harris had an early introduction to down-and-dirty transactional politics. She split up with Brown when he was elected mayor of San Francisco in 1995. He was married, and though he had long been separated from his wife, divorce wasn’t on the cards. In 2003, when Harris ran for San Francisco district attorney and her rivals raised the issue of her relationship with the now retired Brown, whose administration had come under investigation by the FBI for corruption, as well as appointments he gave her during their relationship, she responded:

I refuse to design my campaign around criticising Willie Brown for the sake of appearing to be independent when I have no doubt that I am independent of him – and that he would probably right now express some fright about the fact that he cannot control me. His career is over; I will be alive and kicking for the next forty years. I do not owe him a thing.

After winning that election, Harris ran afoul of the police when she announced that, in keeping with one of her campaign pledges, she would not seek the death penalty in the case of a suspect accused of killing a police officer in 2004. Even Senator Dianne Feinstein turned on her, announcing at the officer’s funeral that the crime ‘is not only the definition of tragedy, it’s the special circumstance called for by the death penalty law’. The remark was directed at Harris, who was sitting in the front row. She lost the support of the police union, though this didn’t stop her being elected as attorney general in 2010 or as senator in 2016. Morain points to a broader pattern in her political style. She tends to defer taking stands on issues for as long as possible. While she was in office in California, she couched this approach as being in deference to existing laws, but it has made her a logical standard-bearer for a Democratic Party that seeks to be all things to all voters in the face of Trump. Some claims made by Harris and others on her behalf at the convention have since been revealed to be inflated: it was repeatedly said that she ‘took on the big banks’ and won, but the $20 billion settlement she gained from lenders as California attorney general did little for those who faced foreclosure. Some received compensation amounting to a month’s rent, while others were forced to sell their homes at a loss; most of the money went back into the state budget. Overall, Morain’s book portrays a canny political fighter against a fascinating backdrop of ruthless, money-soaked California politics. He traces her on-and-off alliance with Gavin Newsom, now governor of California and previously Brown’s successor as mayor of San Francisco, who with Harris administered the country’s first gay marriages; her rivalry with his ex-wife, Kimberly Guilfoyle, now the fiancée of Donald Trump Jr, who rose to prominence in the right-wing mediasphere after prosecuting the case of a pair of defence attorneys accused of manslaughter, after one of a pair of vicious dogs that they were minding for a client, an Aryan Brotherhood gang leader called Cornfed, mauled to death a university lacrosse coach who lived in their apartment building; and her long-standing alliance with Barack Obama.

Obama’s speech on the second night was a medley of his greatest hits, with passages recalling his national debut at the DNC in 2004 and his ecumenical message against the notion of red states and blue states:

All across America, in big cities and small towns, away from all the noise, the ties that bind us together are still there. We still coach Little League and look out for our elderly neighbours. We still feed the hungry, in churches and mosques and synagogues and temples. We still share the same pride when our Olympic athletes compete for the gold.

His list of the malignant forces dividing the nation now includes ‘algorithms’. Obama also, with a hand gesture, made a joke about Trump’s anxieties about the size of his penis.

Michelle Obama was the convention’s most effective anti-Trump speaker:

See, his limited, narrow view of the world made him feel threatened by the existence of two hard-working, highly educated, successful people who happen to be black. I want to know – I want to know – who’s going to tell him, who’s going to tell him, that the job he is currently seeking might just be one of those black jobs?

Trump’s supreme agon is with the meritocratic professional class the Obamas personify. Michelle surprised some in the audience by referring to her own fertility struggles, which had over the first two nights become a leitmotif of the proceedings, an unambiguously pro-family counterpoint to the message against abortion bans. She also reframed the campaign as the return of ‘the contagious power of hope’, casting Harris as a challenger to a failed president rather than a principal in the incumbent administration.

The next evening, I passed through Union Park on the way to meet a few journalists. A few hundred people were gathered to protest the war in Gaza. Jill Stein, the Green Party candidate, was calling for a weapons embargo: ‘Free Palestine! Not another nickel, not another dime, for Harris’s genocide!’ went the refrain. A vote for the Democrats was ‘consent for genocide’ and there should be no more ‘nonsense about the lesser evil’. ‘We have two greater evils being rammed down our throat,’ Stein said. The next speaker, from Students 4 Gaza, drew a parallel between Israel’s war and the ‘scholasticide’ being committed by the local government, which was ‘systematically closing schools in Chicago’. The Democrats were ‘a party that does nothing for us’. ‘A new face for the Democrats will not stop us.’ The goal of the movement was, he said, ‘a sea change in mass consciousness’.

Though the crowd was small, it was a bracing departure from the euphemisms on offer in the hall, where ‘uncommitted’ delegates representing the pro-Palestinian protest votes (the only votes not cast for Biden and transferred to Harris) had their requests to speak turned down. One of them, Georgia state representative Ruwa Romman, a Palestinian American, delivered her refused speech outside the arena. Around seventy arrests were made over the course of the week, and phalanxes of police were arrayed around the arena on the last night for a confrontation that didn’t erupt into violence. The protests didn’t match the historic confrontation in 1968 between Vietnam War protesters and the Chicago police and National Guard, but no one could enter by the main gate to the arena without hearing the names and ages of Gazan children killed since October being read out over a megaphone.

The final two nights brought few surprises. Bill Clinton, meandering and digressive but not uncharming, seemed out to prove he could execute Trump’s improvisational self-referential style in a manner slicker than Trump’s. Oprah Winfrey took to the stage as though to remind the crowd of a time when everybody watched the same things on television, though she now looks younger than she did back then. Tim Walz, the high school football coach turned Minnesota governor, brought onto the ticket for his earnest populist touch and his potential to reach white guys who like sports, told the story of his own family’s experience of the ‘hell of infertility’. I was disappointed he didn’t cast it as a football metaphor, something about the Republicans declaring a touchdown gained by IVF in the fourth quarter a penalty and sending families back twenty yards to kick the field goal of adoption. (He did use some of those metaphors in a closing exhortation to the crowd to donate to the campaign and get out the vote.)

Harris herself reprised all the convention’s themes with poise and confidence, if not quite joy: her family story; coming to the aid of victims of sexual assault such as her friend Wanda; her fights for veterans, homeowners, defrauded and abused elders; her campaigns against drug cartels and for a secure border; her championing of reproductive rights; her loyalty to the middle class. She settled into one of the convention’s slogans as a refrain: ‘We are not going back.’ Not going back to a Trump presidency and not going back to the retrograde vision of America on offer from him and ‘his billionaire friends’. Of late, American elections are decided by a few thousand votes in a handful of states, even when the margins of the national popular vote are in the millions. As I write, the week after the convention, Trump was last seen hawking ‘digital trading cards’ of himself for $99 each, with the promise of a ‘physical trading card’ and a swatch of the suit he wore during the debate with Biden (‘people are calling it the knockout suit’) if you buy a complete set of fifteen. I will be surprised if Trump and Vance defeat Harris and Walz in November. The Democratic Party is the most powerful force in American society. It has won the popular vote in seven out of the last eight presidential elections, and the nation’s organised money and institutions are behind it. A real sea-change will occur when it faces significant resistance from someone other than a gang of rich scumbags and the folks they manage to con.

30 August

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.