Lucian Freud resembled certain film directors – Ingmar Bergman, for example – in that the lead characters in his works influenced the way the creation took shape, often guiding it into entirely new territory. There is an unspoken understanding between the film director and the actor that their involvement isn’t permanent: the actor may be offered a more desirable part, or the director may feel the need to make a different kind of film. The separation is often painful because the collaboration can be intense, especially so if they had loved each other. In the same way, Freud was always moving on, though the ending could be frayed. When the break-up was especially traumatic, it effected a drastic change in Freud’s painting style, as in the case of the end of his marriage to Caroline Blackwood, when a Dürer-like precision was replaced by a Bacon-inspired freedom.

Freud’s first wife was Kitty Garman, the daughter of Jacob Epstein. In Girl with Roses (1947-48), Kitty is shown sitting on an elegant wicker chair with a curved dark frame. The wood looks newly polished, though its perfection is broken by a few tufts of wicker poking through where the armrest meets the seat. She is wearing a black wool jumper decorated with horizontal green stripes, and a black velvet skirt. The textures of the materials are astonishingly conveyed. The thorns on the stem of the rose that Kitty is holding up to her alarmed face are needle-sharp – you can sense their sharpness, and how risky it was to hold the stem. There is a large brown birthmark on the hand holding the rose. The texture of the birthmark is rougher than the porcelain-smooth white of her upheld hand. The flower is a pale pink bud just beginning to open. This discreet opening is a contrast to the cleft that slashes apart the bright red tulip – echoing her lipsticked mouth – in the portrait of Kitty’s aunt Lorna Wishart, with whom Lucian had previously been in love. Lorna was nearly twelve years older than him, and married.

Kitty is wearing no make-up. Her pink mouth has a full underlip and you can see the glint of small white teeth. Her brown eyes are wide open. She is looking towards the light source and her pupils are so precisely defined that they reflect the window divided by the horizontal bar of the window frame she is looking at. The mirror of her eyes reminds me of the mirror in Jan van Eyck’s Marriage of Arnolfini, which similarly reflects the part of the room unseen by the viewer, and the colouring in Freud’s painting, with its ochres and greens, is just as reminiscent of van Eyck.

When Lucian painted his portrait of Kitty, their marriage was nearing its end. Domesticity made him claustrophobic and he was searching for a change. Four years later, Caroline Blackwood looks as if she is dreaming of a voyage in the luminous portrait of her called Girl in Bed (1952), painted near the start of their marriage. There is the suggestion of a misty sea under a pearly grey sky in the background; her beautiful head is supported by her viridian-veined wrist; her hand cups the side of her brow to keep back the waves of golden hair so that her pensive face is revealed in its entirety. Her blue eyes are enormous. She is looking away, into the distance. The line separating the lips of her mouth is as delicate as the central vein of a rose petal. Each hair – on her eyebrows and head – is recorded with a fine sable brush. The only other painter who achieved this perfection of detail without pedantry is Dürer.

The portrait of Blackwood painted in 1956 and titled Girl by the Sea has a very different mood. The sea that had been hinted at in the 1952 portrait has now become much more definite. Blackwood’s profile is framed by turquoise water and a brooding sky. Her sad eyes are lowered and her mouth turned down. Her hair looks thick with sea salt and rope-like curls hang around her face and neck. She has endured an arduous journey and is worn out. Lucian had been compulsively unfaithful throughout the years of their relationship. He had felt, as with Kitty, imprisoned by marriage, though the status of marriage was important to him. Caroline, in her sea-lit portrait, is longing to leave. She needs to be back on land.

When she did leave, Lucian’s world fell apart. He needed to find a new way of painting so that he could control his inner turbulence and panic. He no longer had the equilibrium to keep a steady hand and paint with the precision of Dürer. He had been abandoned, so his painting style needed to be abandoned too. The change in technique coincided with the start of his friendship with Bacon. Bacon suggested that his work verged on illustration and advised him to give up drawing so the paint could take over. The subsequent loosening up of Freud’s painting occurred while his marriage was breaking up. He would never marry again. He needed to free himself from emotional ties and, at the same time, he wanted to be liberated from painterly constraints. He gave up the sable brush for a hog-hair one. The new gestural acrobatics are exciting but something has been lost: the paintings are less charged with romantic tenderness. Disillusionment and sadness – nearly despair – haunted his paintings from now on. The female nude became his main subject matter, and the vehicle for his distress.

Naked Girl, from 1966, is a portrait of Penelope Cuthbertson. It is a powerful representation of vulnerability. Penelope lies on her back on a white sheet, her claw-like hands clutched above her nipples, as if she’s warding off an attack. The red wound of her vagina is like a blister caused by her chafing thighs, which are clenched together. Her ribcage is erupting from her skin like an alien life form. Freud had turned away from realism: his 1960s technique is closer to expressionism.

Frank Auerbach described Cuthbertson as ‘a sweet girl’ who ‘worked with the kindergarten in Brunswick Square’. Freud met her at a party hosted by Blackwood’s brother. ‘Lucian thought there were lots of girls like her, very, very nice.’ The last painting of Cuthbertson is one of my favourite paintings by Freud. It is titled Night Interior and dated 1968-69. Penelope is a small figure in a large, desolate room. You can sense the silence. The big, dark, uncurtained window behind her is lit with mysterious reflections, though the bright light bulb in the ceiling under which Freud must be standing glares. He is quietly watching her. She looks alone, even so, and unobserved. She is sitting sideways on an armchair, her legs thrown over it. An old water tank, plus stained bath and sink, stand on the right of the picture. The bare floorboards rise steeply towards the left, brought to a sudden stop by a tall cupboard in the corner. The door of the cupboard is ajar, and you can see Freud’s grey overcoat inside, suspended on a hanger: a signal that it was time to leave. Freud was in love with someone else.

Jacquetta Eliot was Freud’s next great love. She was an heiress, renowned for her beauty. The paintings Lucian made of her are full of intensity; the specificity tells you how much she mattered to him. They represent a homecoming. He wanted to return to his earlier meticulousness, though he didn’t replace the coarse hog-hair brushes he was now using with his old sable brushes. ‘Concentration is everything,’ he used to say. He shifted away from Bacon’s influence. It became important to record every detail, as he had done in the portraits of Kitty and Caroline. The precision of his early work returns, now with a freer rendering. Nothing is fixed. Jacquetta seems always to be in movement.

In 1972, as he was falling in love with Eliot, Freud started to paint his mother. He had never been able to paint her before. He had always found her concern for him intrusive. He interpreted her loving focus as curiosity he didn’t welcome. He became secretive. But after her husband’s death two years earlier Lucie Freud had tried to kill herself. She lost interest in the world and stopped worrying about her son. Her new lack of concern liberated him. His paintings of her are some of the most memorable he ever made. Each is distinct and urgent.

Freud brought his two loves together in Large Interior W9 (1973). His mother sits in a black armchair, her hands resting on the arm. Her wedding ring is plainly visible. She is warmly dressed in a grey wool suit and bolero. By contrast, Eliot, behind her, is lying naked to the waist on a narrow bed. A brown blanket covers the lower part of her body. Her arms are raised and crossed behind her head. She is looking upwards with a rapt expression. A pestle and mortar under Lucie’s chair are surreal additions to the painting, and lead one to question the symbolism of the connection between the two women – to each other, and to Freud himself. They were both mothers with three sons, and neither had left their husband.

In 1975, Freud and Eliot split up. Their relationship had been too tempestuous to last. They both had affairs. They made each other jealous. This was sexually stimulating but unsustainable. The painting of her known as Last Portrait is unfinished. It is a painful image of loss and grief. Lucian took a long time to get over her.

Head of a Girl (1975-76) shows Katie McEwen. Katie was sixteen when Lucian started sleeping with her. She was a talented artist, the daughter of friends. In Lucian’s portrait she looks tragic. Her eyes show absolute despair. For me, this is the saddest and most haunting of all his portraits. When Katie and Lucian separated, she went on to enrol at the Slade School of Art, where I was also a student.

Lucian’s first portrait of me is titled Naked Girl with Egg and dated 1980. I had been going out with him for two years. I had met him when he was a visiting tutor at the Slade when I was 18 and he was 55. I was twenty when I started sitting for him. I was a very romantic, self-conscious young woman. My voluptuousness (as Lucian described my curves) gave me a maternal air. I offered the notion of comfort to Lucian, which he felt badly in need of. But the intimacy that evolved between us was a challenge for him. He was threatened by it. He told me that he preferred to have sex with strangers and that he abhorred the constraints of monogamy (for himself, though it was a quality he particularly respected in couples he knew). He needed to turn me into a stranger so that he could paint me.

Naked Girl with Egg is a cruel objectification. I am shown lying on a black bedsheet; one hand cups my full breast, the other is raised to my excruciated face. A halved boiled egg sits in a white dish on a marble-topped table. The brown swirling veins of the marble echo my pubic hair and the egg resembles my breasts. The painting was bought by the British Council and widely exhibited. It has been included in most of the important Freud shows. Sarah Lucas’s self-portrait Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab, a powerful feminist statement, had no impact on the art world’s conscience.

Between 1980 and 1985, Lucian worked on a small portrait of me, the mood of which is the complete opposite to Naked Girl. It is titled Girl in a Striped Nightshirt. Lucian had bought me a blue and white nightshirt made of brushed cotton to wear for the portrait. It was very soft and comfortable. My head is resting on the curve of the sofa’s arm and one hand lies close to my face. I radiate peace. Over the years, Lucian and I had grown close. He had lost his fear of intimacy with me. The painting, I think, is an image of love. It took two years to finish. During that time, I got pregnant and gave birth to our son, Frank Paul. After the birth, a distance started to impose itself between Lucian and me.

I am and always have been dedicated to my own painting, and ambitious for it. I had managed to organise my time so that I could paint and sit for Lucian with equal commitment. But after I had Frank, I became less available as a sitter. I was also gaining recognition as an artist and had my first solo show in 1986. It was a success. Lucian started to look for someone to replace me. I noticed that there were often muddy paw prints left on the smooth white floor of Lucian’s kitchen. And I found a hair slide with a dark strand of hair clinging to it on the bed.

Triple Portrait (1986-87) is a portrait of Susanna Chancellor, Lucian’s new lover. Susanna is seen in profile sitting on the studio bed in front of a pile of paint rags. Two whippets are lying at her feet and she is resting her hand on the one turned towards the viewer. The dog is more acutely observed than Susanna, whose face is in shadow and half-hidden by her hair. She was to remain Lucian’s companion for the rest of his life and he painted her often, yet somehow none of the portraits of her has the same stamp of urgency – an unforgettable urgency – as the paintings of Kitty, Caroline, Jacquetta or Lucie, or perhaps of me.

Lucian’s involvement with Susanna occasioned another change in technique. He started to apply paint more thickly. Auerbach now supplanted Bacon as the painter Freud was most affected by. In Triple Portrait, the three figures seem suffocated by the impacted paint.

Lucian had a big retrospective at the Hayward Gallery in 1988. Bacon wrote a letter to his friend Eddy Batache to say what he thought about it. (A bitter rivalry now existed between them. Bacon had rivalrous feelings towards Auerbach, too, thanks to Auerbach’s close friendship with Freud.) ‘Lucian Freud’s exhibition’, Bacon wrote, ‘is here now to great acclaim – I was myself very disappointed in his new style it is a mixture of Frank Auerbach and a painter who used to show at Helen Lessore [Gallery] called John Bratby – Lucian’s work seems to be just a display of technique.’ I can’t help thinking he was referring particularly to the portrait of Susanna with two whippets.

Susanna lived with her husband, Alexander Chancellor, and their two daughters. She and Lucian had known each other for many years, during which they had conducted an on-off affair. Now it turned into a more serious relationship. Susanna didn’t want to be painted nude. She was hard to pin down. Lucian was tantalised by her but never captured her, though he kept trying. His most successful paintings from this period were of men. The paint remained thickly applied, but acquired more and more energy and freedom.

Naked Man on a Bed (1989-90) is a portrait of the artist and writer Angus Cook. It is compassionate, softly lit with a pearly pink glow. Angus is shown lying on a grey blanket with one arm raised above his head and the other laid on his heart. The loving detail of the furry line of hair leading to his navel and surrounding it like a nest indicates some reciprocity between artist and sitter. There appears to be mutual trust and understanding. For this moment, at least.

Angus became my closest friend. I met him when I was at the Slade and he was studying English at University College London, to which the Slade is attached. Soon after I got to know him, he started sitting for me. Lucian saw a charcoal drawing I’d done of Angus and said he needed to paint him.

All Lucian’s portraits of Angus have a special tenderness, and a knowledge of the way Angus’s body looked in movement. The portraits of him are never static. In this way, they remind me of the confident fluidity of the portraits of Eliot. Angus introduced Lucian to his friend Leigh Bowery, who soon started sitting. Bowery knew intuitively what Lucian required. As a performance artist, he understood the theatricality of the situation. He was committed to sitting but was never enslaved by it. The portraits of Leigh are admiring. They are not called ‘Naked Man’ but ‘Leigh Bowery’. Artist and sitter share the power equally. Leigh became the lead actor Lucian had been looking for his whole life.

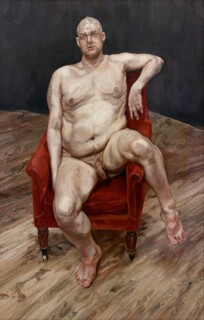

Leigh Bowery (Seated), from 1990, is Freud’s last masterpiece. Bowery sits naked on a red velvet chair. One leg is draped over the side of the chair; the foot of the other leg rests on the bare floorboards. He is looking straight at the viewer. One eye is lit up, one eye in shadow. He had been diagnosed with Aids. His expression shows that he is facing death. There is nothing he can do to survive. His acceptance gives the painting its spiritual force.

The painting left unfinished on the easel at Lucian’s death in 2011 was of his assistant David Dawson. David’s dog, Eli, is sleeping faithfully at his side. During the last months of his life, Freud didn’t have the stamina he once did. He would work on the painting of David every day, adding small dabs of pigment, and then he would need to rest. I find its incompleteness inexpressibly poignant, indicative of a lifetime of unwavering commitment to the process of painting and a testament to the enduring love and trust that Lucian could feel for men. He never trusted his female lovers to the same extent.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.