On 13 May 1397, the visitors came to Ruardean in Gloucestershire. They learned that Nicholas Cuthler was causing a scandal among his neighbours. He had not come to terms with his father’s death and was making strange claims: he went about in public saying that his father’s spirit still walked the village at night. One evening he even kept vigil beside the tomb from dusk till dawn, waiting for the ghost to come. Nothing else is known about Cuthler, who was born six and a half centuries ago. His case happened to be written down by a scribe – and meanwhile he went on with his days, or so we must suppose. As is usually the case with medieval legal records, lives flash before our eyes and then vanish. The flashes are what make the archives so tantalising. You can wait a long time before you get one.

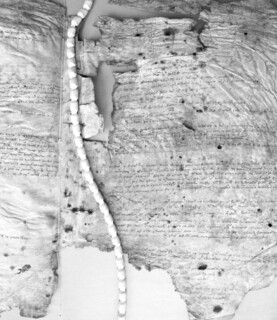

Cuthler’s scandalous grief was recorded in a booklet of about fifty pages, among more than a thousand other parish reports from the diocese of Hereford in 1397. These were the results of an inquiry called a visitation, whereby church authorities attempted to discern the state of religious life in the parishes. Local worthies sent reports to the bishop, John Trefnant, who processed through the diocese with a cadre of officials to investigate, judge and correct any troublesome behaviour. The visitation book, ‘an unsightly and tattered manuscript’, was discovered in the archives of Hereford Cathedral in 1907. The next year Arthur Thomas Bannister became a canon there. His appointment had been somewhat controversial: a man ‘of singular simplicity and directness’, he was known for his liberal sympathies and a tendency to blurt out information about church assets. But he slowly rose through the ranks to become precentor, and spent his dotage working on the cathedral’s medieval manuscripts.

In the course of his research, Bannister struck up a correspondence with Montague Rhodes James. Though he is now more famous for his ghost stories, M.R. James was one of the most important medievalists of his time. He had an eye for a sharp detail: privately he described Bannister as a ‘good sort’, but ‘with much to contend with: among other things a terrific wife with a large head of white hair and tortoiseshell spectacles, who appears to be the worst scandalmonger in the county’. James regularly visited Herefordshire to stay with Gwendolen McBryde, an eccentric widow who ran a stud farm. She had married a close friend from his undergraduate days, who died unexpectedly when she was three months pregnant. (‘Monty’ became legal guardian to her daughter, Jane.) After James’s father died a few years later, the McBryde house at Woodlands became a second home for him – his letters to Gwendolen, which she published posthumously, make up the bulk of his surviving correspondence.

It was during one of his Herefordshire sojourns, in 1917, that James underwent his only recorded experience of the supernatural, during a visit to the 12th-century church of Garway. ‘We must have offended something or somebody,’ he wrote to McBryde, cryptically. ‘Probably we took it too much for granted, in speaking of it, that we should do exactly as we pleased. Next time we shall know better. There is no doubt it is a very rum place and needs careful handling.’ The visitors to Garway in 1397 might have agreed. They found no ghosts, but much lively scandal. The priest Thomas Folyot ‘frequents taverns in an unruly and excessive manner’, and had revealed the confession of one of his parishioners during a drinking session. Another man, Hugyn oth’ Walle, was cited for abusing his wife, ‘often threatening to kill her and beating her terribly’. The parish chaplain could not speak Welsh, yet ‘most parishioners there do not know the English language.’

Throughout the 1920s, James and Bannister worked together to produce a catalogue of the manuscripts in the Hereford Cathedral library. But it was not until 1929 that Bannister published a transcription of the visitation book, in a series of articles in the English Historical Review. James commended his friend, ‘whose services to his Church and its archives have been manifold’. In truth, Bannister’s work was a little sloppy, silently omitting substantial parts of the working record; for example, he redacted the ut credunt, ‘as they believe’, that followed the parishioners’ report on Cuthler – a sounding of doubt that was lost in his transcription. Now, in a new critical edition by Ian Forrest and Christopher Whittick, the visitation book is available in full translation for the first time.* As they write: ‘It is not an objective record of what was happening in medieval parishes, being in fact much more fascinating than that.’

In 1397 the visitors would have approached Cuthler’s parish of Ruardean with some trepidation, ghosts or not. It lay in the Forest of Dean, a district marginal even by the standards of the Welsh borders. Shallow seams of iron ore were excavated by shovel and pick in open-face mines; industrial quantities of charcoal were produced for the countless forges of a forest that must have seemed as though it was perpetually aflame. Living within the royal forest and its distinct legal regime, the men of Dean claimed special privileges that they were willing to defend by force. In the 1430s, after a dispute over tolls, they launched a series of attacks on grain barges heading down the Severn for Bristol. An indictment described them as ‘a wild people close and adjacent to Wales’, alleging that ‘the whole community of the Forest … cares nothing for the law, its officers or its procedures.’

At Ruardean the omens were not good. The chaplain failed to appear, the church’s chancel was found in a ruinous state and its revenues – supposed to be used for maintaining a priest – had been sold off without permission. But the parishioners, or at least the clutch of prominent men who supplied the visitors with information, were more accommodating. For some, visitation was an opportunity to speak truth to power; to tell a sombre ecclesiastical official in his expensive robes what needed fixing. The vast majority of reports concerned sex out of wedlock, which disrupted the household, the basic unit of patriarchal authority. The offence was often called ‘incontinence’ in the records: a failure of restraint. Its victims were usually the women and children left out in the cold. In Ruardean, apart from Cuthler and his father’s ghost, all anyone had been talking about was Margaret Hobys, a married woman who had been having an affair with a single man called Nicholas Boweton. Summoned before the judges, the shamed couple could not bring themselves to deny it. They swore an oath of atonement. They were assigned penance: they would be beaten around the parish church six times, and another six times through the market-place. At Staunton, the parishioners complained to the visitors that Thomas Smyth had ejected his wife from their house, ‘denying her food and clothing and other conjugal rights’.

Trefnant’s officials were on the lookout for other kinds of disturbing behaviour too. The Lollard heresy had spread from the teachings of John Wycliffe at Oxford in the 1370s, gaining some traction in the West Country. A decade later, two prominent Lollards were preaching along the Welsh border that the Eucharist was just bread, the pope was the Antichrist, and – even more controversially – that women could administer the sacraments. By the time of the visitation, Trefnant himself was conducting a heresy trial against the squire of Croft Castle. Yet his visitors found nothing: not a single Lollard. Omnia bene, said more than a fifth of the parishes: all is well. If visitation seemed to some a chance to complain, for others it represented an intrusion. Who wanted to be told their church vestments needed replacing, or to traipse off to the nearest town to be solemnly scolded? At Mitcheldean, another forest village, the report gave a simple omnia bene, but a later note claimed that the official sent there ‘dare not cite the parishioners’.

Welsh names are scattered through the 1397 record, and it is clear that relationships frequently traversed ethnic or linguistic divides. At Turnastone, a man called Richard Gogh was said to be consorting with various women: Helen, daughter of Trahaearn, and Lleucu, daughter of Einion, and Lleucu Kedy – all probably Welsh – but also with the more English-sounding Margaret Hunt. Another woman in the village, accused of fornication, was named as ‘Gwladus, otherwise Alison’. But this cross-cultural flux was under threat. A few years after the visitation, a legal dispute involving the Welsh nobleman Owain Glyn Dŵr got out of hand: he named himself Prince of Wales, assembled an army and burned down the town of Ruthin, before proceeding to attack Denbigh, Rhuddlan, Flint, Oswestry and Welshpool. There followed a six-year military confrontation between Welsh armies and the newly established Lancastrian dynasty of Henry IV.

By 1405 Glyn Dŵr was able to command the support of much of western Wales, had secured a treaty of friendship with the French, and had even enlisted two important English nobles, Sir Edmund Mortimer and Henry Percy, earl of Northumberland, into the rebellion. He wrote to Pope Benedict XIII, exiled in Avignon, seeking approval for a plan to restore Welsh law and to elevate the Welsh Church to an archdiocese that would appoint suffragan bishops to Exeter, Bath, Worcester, Lichfield and Hereford. No more English visitors. But the Welsh were ill-equipped to take English castle towns on a permanent basis. Glyn Dŵr’s forces were always most effective as guerrillas among the trees, and gradually they lost the element of surprise. English counteroffensives wore them down and ravaged the surrounding countryside. Percy died in battle in 1408, Mortimer at the siege of Harlech the next year. The Welsh rebellion was not defeated by some great confrontation, it simply dwindled. Nothing was seen of Glyn Dŵr after 1412, dead or alive.

Ihave never seen a ghost. Like M.R. James, I grew up in Suffolk, but have long been drawn to the West of England for research. The dirtier and more tattered manuscripts in Hereford’s collection still hold surprises. A few years ago I was examining a 15th-century act book – the record of a later church court – when I noticed something strange about the thick parchment cover: it was not bound but folded in on itself, creating a kind of envelope. Carefully prising apart the creased edges, I found inside a slip of paper, apparently tucked away more than five centuries ago and forgotten. William Stretford was sworn innocent of stealing twelve sheep. Now we know.

Heading south-west out of Hereford, the Black Mountains loom in the distance. Coming off the main road, as the bishop’s officials regularly had to do, the lanes thin into gravel tracks that swirl around the hillsides. Fields bulge and swell in all directions, the land seeming everywhere to rise, blocking any view of the territory as a whole. Just before the border with Wales, a side road takes you to Kilpeck. Set apart from the village, opposite a barnyard, is a beautiful Romanesque church the colour of marmalade. The sandstone was mined locally, but the church’s soul transmigrated from Byzantium. From the outside it is squat, spireless and heavy-set; inside it is whitewashed and airy, connected by a symmetry of graceful arches and a vaulted apse. Pevsner called it ‘one of the most perfect Norman churches in England’.

It is famous – in certain circles – for its programme of mysterious carvings around the exterior walls. Dozens of haunting faces, human and animal, and other creatures in-between, peer down from the corbels that support the roof. One is a sheela-na-gig: a female figure who stands and reaches behind her legs to expose her genitals to the viewer, a strange grin on her face. The symbol appears in Romanesque churches scattered across north-west Europe, but its significance is unknown. In 1397 the parishioners of Kilpeck presented the visitors with the usual ensemble of fornicators and adulterers. Maiota Leduart with John ap Gwilym ap Rhys (the chaplain, no less); John Hull the piper with Alison, a blood relative of his former wife; David Webbe with Eve Elvell. Most of them were reported to be ‘outside’ the parish; that is, beyond the reach of the bishop’s crozier. But one more thing, reverend father: ‘John, chaplain, as it seems to them, is not firm in his faith, because he has often made boast that he goes about at night-time with fantastic spirits.’

Kilpeck was James’s local parish during his stays at Woodlands with the McBrydes. Every Sunday they tramped over the fields to the church. James, a fine public speaker, was occasionally called on to read from the New Testament in Greek during the services, obliging ‘as unostentatiously as possible’. At lunch afterwards he would impersonate a country vicar delivering a boring sermon until they begged him to stop, or give Falstaff’s speech from the Merry Wives of Windsor. Woodlands is the likely setting for his story ‘A View from a Hill’, in which Fanshawe, ‘a man of academic pursuits’, visits a squire friend in the West of England at the height of summer. Surveying the wooded landscape through a pair of field glasses, Fanshawe notices a hill in the near distance where there is a clearing; he can make out some men with a cart in the field, and, more menacingly, a gibbet. Looking with his own eyes, there is nothing to be seen – Gallows Hill is covered in trees. ‘It must be something in the way this afternoon light falls.’

The squire’s old butler, Patten, does not like them using the field glasses, bought at the estate sale of a local antiquary who died in mysterious circumstances. That night Fanshawe has a dream:

He was walking in a garden which he seemed half to know, and stopped in front of a rockery made of old wrought stones, pieces of window tracery from a church, and even bits of figures. One of these moved his curiosity: it seemed to be a sculptured capital with scenes carved on it. He felt he must pull it out, and worked away, and, with an ease that surprised him, moved the stones that obscured it aside, and pulled out the block. As he did so, a tin label fell down by his feet with a little clatter. He picked it up and read on it: ‘On no account move this stone. Yours sincerely, J. Patten.’

As often happens in dreams, he felt that this injunction was of extreme importance; and with an anxiety that amounted to anguish he looked to see if the stone had really been shifted. Indeed it had; in fact, he could not see it anywhere. The removal had disclosed the mouth of a burrow, and he bent down to look into it. Something stirred in the blackness, and then, to his intense horror, a hand emerged – a clean right hand in a neat cuff and coat sleeve, just in the attitude of a hand that means to shake yours. He wondered whether it would not be rude to let it alone.

The waking Fanshawe cannot let alone either. The next day he takes a bicycle ride out around the surrounding villages. He gets a flat tyre and decides to take a short cut home – over Gallows Hill.

James devoted his career to thinking about what it meant to look through dead men’s eyes. Though much of his early work attempted to trace biblical apocrypha, he had come to some prominence in 1902-3 for his role in the excavations of the Bury St Edmunds abbey. In the 1890s he had discovered – on the flyleaves of an obscure 14th-century manuscript – a contemporary description of the abbey, which allowed him to piece together the topography of the church. From this he was able to ascertain the location of several lost graves containing its medieval abbots, information that had been lost since the Reformation. The graves were excavated to much public interest. In the excitement the bones were removed for safekeeping, possibly being mixed up in the process. Later that month, James received a letter reporting – with great relief – that ‘the abbots were most comfortably replaced this morning.’ The following year James published his first collection of fiction, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary. The last story is ‘The Treasure of Abbot Thomas’, which proceeds exactly as one might expect.

James spent much of his life grappling with what it means to unbury the dead. But he was never able to dislodge the sense that if we disturb the past, it will soon return to disturb us. To rifle in the archives is to interfere with the traces of people whose existence has reached far beyond natural mortality. There is a great strangeness in this, but to abide with it is the duty of any historian. We can visit the dead, but only on their terms. Or we can keep vigil and wait for them to visit us.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.