Tudor art has a poor reputation. Compared to the works of the Northern and Italian Renaissance, 16th-century English paintings look provincial. Tudor patrons weren’t generally prepared to pay much for pictures, and were more concerned with the documentary function of a painting, its cost and size, than with its aesthetic qualities. A proclamation of 1563 recommended that London painters be paid less than carpenters and goldsmiths. Much of the labour was done in workshops by assistants who used pattern books to reproduce designs.

Things were different at court, where foreign luxuries were prized and European artists welcomed – most notably Hans Holbein the Younger, who spent the last decade of his life in England. The influence of their work slowly began to be felt: court artists such as Nicholas Hilliard were shaped by their admiration for Holbein, and by the 1570s refugee artists from the Netherlands were inspiring many now unknown English painters to attempt greater tonal subtlety and more complex compositions. Native practices began to merge with more sophisticated Continental painterly traditions.

As for religious painting, even extreme Protestants found biblical scenes acceptable in domestic chapels and common rooms. The Tudors favoured moral themes from the Old Testament (and, to a much lesser extent, the New Testament), especially parables, which featured on everything from ceramics to furniture fittings, plasterwork and murals. These arts flourished under both Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, as wealthy householders sought to surround themselves with beautiful and edifying objects to guide charitable behaviour. Unlike paintings on panel, such decoration wasn’t intended for prolonged contemplation: that, after all, would encourage idolatry, which had been purged from churches during the Reformation. Tudor merchants had their portraits painted for display in civic or charitable institutions, as well as in their own homes. Like their Dutch counterparts, they were concerned to appear virtuous, dressing in black to signal their sobriety. Such portraits had personal and institutional significance, but most had no exchange value. Cheap oil paintings quickly lost their freshness. Only a small percentage of painted portraits from the period survive.

By the last decades of the 16th century, the notion of the portrait gallery had taken hold. Galleries were built in private homes to display paintings of notable men and women and illustrate dynastic allegiances. Oxbridge colleges commissioned portraits of significant figures from their past to show their own genealogies. The middling classes commissioned cheap heraldic paintings with invented coats of arms. There was gradually more work for artists, especially in London, where less successful painters displayed their pictures on walls along the Strand while the more ambitious claimed shop windows.

Christina Faraday’s book seeks to understand the ways in which the Tudors thought and spoke about art and, in particular, the excitement and dangers posed by artworks that seemed almost ‘alive’. Such beguiling works could both instruct and seduce. Significantly, their power lay not in the degree of naturalistic representation achieved by the artist but in the vivid liveliness, or enargeia, brought to the design by other means: through decoration, inscriptions and emblems, all carrying meaning for the viewer.

Holbein appears only briefly in Faraday’s account. He was, as she points out, an anomaly. It wasn’t just that the English didn’t use linear perspective: they hardly understood the concept. It might seem obvious to us that patrons ought to have preferred a Holbein painting to one by a local portraitist, but Faraday is sceptical. ‘While illusionistic portraits by Hans Holbein and Hans Eworth would have been present in English collections throughout the period,’ she writes, ‘it is doubtful whether patrons recognised these qualities in them … For their own commissions English patrons often favoured another mode of representation, such as the emblematic or inscriptional.’ Delight and awe might be part of a work’s rhetorical function, but they were not its raison d’être. As Faraday reminds us, ‘fine’ art wasn’t distinguished from the great range of decorative and decorated objects with which the Tudors surrounded themselves. This was a world of tapestries and embroideries, plasterwork and panelling, illustrated books and manuscripts, carvings, metalwork, murals and every sort of embellishment.

Faraday’s use of the terms of rhetoric to describe the strategies of Tudor artists is helpful, but only up to a point. Quintilian, whose Institutio Oratoria was known to every Tudor schoolboy, urged rhetoricians to convey their arguments clearly, concisely and quickly; Faraday identifies a corresponding attitude in the fine brushwork and economic format of the portrait miniature. Eyes, for example, were quickly outlined with a few strokes. The Tudors and their European counterparts ascribed great power to the miniature, which was never more than two or three inches in diameter, designed to fit in the hand. It was considered the equivalent of a brief encounter, a way of summoning the sitter. When Henry Unton, Elizabeth I’s ambassador to France, was asked by Henri IV to give his opinion of Henri’s mistress, Gabrielle d’Estrées, Unton instead produced his miniature of the English queen, saying that Elizabeth was a ‘far more excellent mistress’. Henri was enchanted by the picture – which, as Unton put it, ‘did draw more speech and affection’ from the king than all his ‘best arguments and eloquence’.

Novel techniques helped to intensify the effect of the portrait miniature. Hilliard used powdered gold to create a background of flames behind a lovestruck young man – the flames would have seemed to flicker in the light. Flaming portraits were a genre in their own right – a number survive – and here Faraday’s framework starts to look rigid. It isn’t clear that works like these had, above all else, a singular rhetorical purpose. Does fire indicate sexual passion or, alternatively, a chivalric courtly milieu in which men advertise their fierce devotion to the queen? Perhaps it signified spiritual commitment to the Protestant cause? Or all three? We might wonder whether Hilliard enjoyed the ambiguity: the unknown man in his portrait wears an emblem round his neck, which could have given us the necessary clue, but he is hiding the image it bears.

Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533) followed the European tradition of illusionistic portraiture, in which individuals are shown in a realistic setting, surrounded by the attributes of their wealth and learning. By comparison, a rather flat-looking portrait of Unton, painted by an unknown British artist some sixty years later, has him occupying only a quarter of the canvas, which is otherwise taken up by scenes from his life: Unton as a baby surrounded by women; Unton as an Oxford student surrounded by men; Unton in mixed company at a feast with his household. The difference is due in part to function – the picture was commissioned by Unton’s widow, to narrate his life to future generations of the family – but it also reminds us that Tudor patrons didn’t value naturalism or single-point perspective as later viewers have. The Unton memorial portrait is busy with narrative, presenting its subject in all his aspects, professional and personal, with emblematic figures – Death wielding an hourglass, Fame blowing a trumpet – rounding out the story.

The Tudors could be extravagant in other media, often building on foreign expertise. Consider John Caius’s memorial in Cambridge, probably carved by Theodore Haveus, a Fleming or German from Cleves who settled in England in 1562. After Caius’s death in 1573, his tomb lay above ground for the next six decades. Anyone entering the chapel would first have seen the inscription ‘VIVIT’ (‘he lives’). Then, walking around the tomb, they would have read the full inscription: first, ‘He lives after burial’; then, ‘Virtue lives after burial’; and, above the tomb, ‘FVI CAIVS’ (‘I was Caius’). The design was intended to commemorate in marble a man whose example would impress young minds. Visual liveliness – scrolls and whorls, gilt and scarlet – enhanced the effect, seeking to combine edification with pleasure.

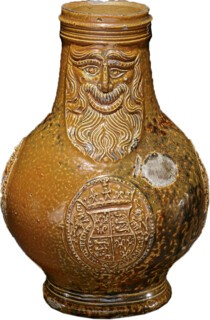

Tudor book illustrations owe much to German, northern Italian and French printmaking, and European woodcuts were often carefully copied when making translations. Innovations such as fold-out pages were also adopted from abroad, and often used in works of geometry and anatomy. In tapestry, too, the English relied on designs from elsewhere, particularly Italy and the workshops in Brussels, where Old Testament scenes were depicted with proper perspective. Bartmann jugs, imported from the German Rhineland, were especially popular in Tudor England. Linked to folklore about wild men, they usually show a heavily bearded and grinning man on the upper half, with heraldic motifs below. Potters in Cologne began adding Tudor roses to the jugs they supplied to the English. The Tudors wrote little about art, and even less about design, so it’s hard to know whether Faraday’s interpretation of the reason for the jugs’ popularity – that Protestant Tudors would have registered an association between the fragility of humanity and the fragile clay vessel – holds true. The jugs were often seen in homes heavily decorated with moral inscriptions and religious images, which the good housewife or husband might have referred to when speaking to the servants or children. But perhaps their owners just found them funny.

In the decades after the death of Elizabeth I, Continental influences came to dominate perceptions of art in all genres. Thomas Howard, the earl of Arundel and a diplomat under both James VI and I and Charles I, represented a new kind of ruthless art connoisseur and collector, hunting for classical statues as well as bargain works by Holbein and Dürer during the Thirty Years’ War. Contemporary commentators began to frame much of Tudor art as an ‘insular mistake’ or a ‘patriotic lie’. We have yet to shake off their legacy.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.