There has been more than one revival of interest in the mayfly career of Pauline Boty since her death in 1966 at the age of 28. In accordance with Cecil Beaton’s dictum that it takes slightly longer than 25 years for a cycle of taste to complete and for the merely dated to become historic, it was in 1993 that the Barbican put on The Sixties Art Scene in London, which featured several of her paintings. Its curator, the art historian David Alan Mellor, had been fascinated by the subject in general and by Boty in particular since, as a 13-year-old, he saw Ken Russell’s television film Pop Goes the Easel. Shown as part of the arts series Monitor in 1962, it purported to follow a day in the life of four young artists: Boty, Peter Blake, Derek Boshier and Peter Phillips. For Mellor, growing up in ‘meagre’ circumstances in the East Midlands, London as the Sixties started to swing was a revelation, ‘a vision of something wonderful’. After she died Boty’s work wasn’t seen for years, but while he was researching the Barbican exhibition Mellor got in touch with her daughter, Boty Goodwin, who was then in her twenties. She took him to the family home in Kent and he saw a cache of her mother’s paintings, which transformed his ideas: ‘Suddenly the whole history of British Pop Art was different.’

Well, yes and no. As Marc Kristal suggests in the introduction to his widely researched and delicately judged biography, there was an element of ‘infatuation-driven hyperbole’ in Mellor’s assessment, as there has been in almost everything that has been said and written about Boty. In her lifetime her physical presence was always part of her reputation. It wasn’t just that she was beautiful, but that she was beautiful in a particularly timely way. Blonde, long-limbed, slightly lush, she was the Sixties ideal. The headline on an interview with her in Vogue in 1964 was ‘Living Doll’. In person she had an un-doll-like vitality. Keith Johnstone, a director at the Royal Court Theatre, for which she designed posters and programmes and later acted, described her as ‘so full of life that her skin seemed hardly able to contain her’. The film producer Tony Garnett remembered ‘a force of nature … She had a joy in her, a love of life … everybody seemed to fall in love with her’. She knew the effect she had and she was self-possessed and confident enough to exploit it. She posed nude with her pictures, was a dancer on the TV show Ready Steady Go!, and appeared in other films as well as Russell’s, including Alfie with Michael Caine.

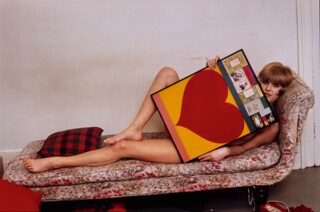

How much of her reputation came from her art and how much from herself is a question that haunts Kristal’s book as well as Pauline Boty: A Portrait, the catalogue for an exhibition of her work at Gazelli Art House earlier this year. Both have covers featuring Boty with one of her best-known paintings, With Love to Jean-Paul Belmondo (1962). On the Gazelli book she sits below it, wearing a high-necked dress and looking down coyly at the cat on her lap. On Kristal’s she is in front of it, staring straight out, naked. Boty saw parallels between herself and Marilyn Monroe, whom she painted both before and after Monroe’s death, and after Boty’s own death the comparisons were yet more resonant. The bigger question, perhaps, is whether it matters to detach the woman from the work. In a discussion of the Barbican exhibition on BBC2’s Late Show, the critic Waldemar Januszczak gave his opinion that Boty was no more than a personality cult. She was, he said, a ‘bad’ and ‘derivative’ artist, who was remembered only because she was a ‘dolly bird’. Between the coarseness of that misjudgment and Mellor’s infatuation there is, as Kristal implies, a way of appreciating ‘Pauline Boty’ as a compound fused in the moment that gave rise to Pop Art, a moment of self-conscious celebration that Boty both embodied and described memorably as a ‘nostalgia for NOW’.

Born in Croydon in 1938, she was the daughter of Albert and Veronica Boty. Albert was a chartered accountant, and the family were comfortably off. Boty’s voice struck the young Mellor when he heard it in Pop Goes the Easel as ‘very posh’: ‘You heard a voice like that, you realised it belonged to a student who probably owned a suede coat.’ Veronica was a housewife and there were four children (three boys, including twins), who teased their sister until she was ‘just a screaming maniac’. The future ‘Wimbledon Bardot’ was known at home as ‘porky Pauline’. Albert clung rigidly to the conventions of interwar suburbia, all the more tightly perhaps because he was not British. Born in Bushehr to a Persian mother and a Belgian sea captain father, he was a pipe-smoking, cricket-loving, tea-drinking simulacrum of an Englishman. His ‘Victorian’ ideas, which Boty recalled he ‘tried to vaguely impose’, not wanting her to have a job for example, caused tension. Her brothers remembered ‘terrible rows’ when she would ‘take him on before breakfast’. Yet perhaps the element of performance, the deliberate projection of a partly constructed personality, was something she inherited.

When Pauline was ten this ideal nuclear family imploded. Her mother fell ill with TB, her father delegated home life to the 14-year-old John and chaos ensued. In some ways it was liberating, as Boty recalled in the long interview she gave in 1965 to Nell Dunn for her book Talking to Women. With her mother in hospital or at home bedridden there was ‘a fantastic amount of freedom’, but there was also the first of those spells of depression that would recur throughout her life. At Wallington County School for Girls the teenage Boty was an instant star. Her younger contemporary, the designer Stella Penrose, remembers her acting in The School for Scandal. ‘She just oozed sexuality … she burst out of her body … It was marvellous. But also shocking.’ In 1954 Boty left to go to Wimbledon School of Art on a scholarship to study painting. Soon afterwards, spotted at a New Year’s Eve party wearing black stockings, she was the talk of Carshalton. ‘Well, no one wore black stockings,’ Penrose remembers, ‘so it was “Ahhh”.’

Wimbledon, however, was not exciting. The painting department was stuck in a prewar rut. The only stirrings of the revolution about to overtake British art schools were in the stained glass department, overseen by a dynamic young teacher, Charles Carey. Boty’s switch of disciplines was, Kristal suggests, ‘the most important choice of her creative life’. Carey was an inspiring teacher and stained glass was having a moment in the avant-garde. Almost the only form of decoration acceptable to Continental modernists, in Britain it suited the softer Neo-Romanticism of the postwar years. Coventry Cathedral was under construction from 1956. Perhaps its most spectacular feature is the 26-metre-high baptistery window by John Piper, and Piper’s influence, possibly transmitted via Carey, is evident in Boty’s 1957 lithograph of Notre-Dame.

By the time she arrived at the Royal College of Art the following year, it was ‘the place’, as the artist Allen Jones put it. The principal, Robin Darwin, hadn’t just brought it back from postwar torpor, he had reconnected it with industry and architecture. Windows for Coventry, designed by the RCA’s head of glass, Lawrence Lee, and his former students Keith New and Geoffrey Clarke, were being constructed nearby at the V&A. When they were exhibited in the sculpture hall their monumental scale made a huge impact on the students. As one of Boty’s contemporaries put it, ‘Painting? Too small!’ There was also the fact that there was much less competition to study stained glass than for painting. Boty’s decision no doubt had an element of pragmatism.

It was out of the stained glass department that the RCA’s most interesting group of critical activists, Anti-Ugly Action, emerged and with it Boty’s public image was born. Impatient with the banality of postwar urban architecture, the Anti-Uglies took to protesting outside buildings they disapproved of, such as the new Kensington Central Library. Sometimes they dressed up as Victorians, or as Christopher Wren in a bath chair, and carried a cardboard coffin symbolising the moribund state of affairs. Boty, in costume as a Dresden shepherdess, naturally caught the public eye. Interviewed by the Daily Express in 1959 she pronounced the Air Ministry building ‘a real stinker’, along with the Farmers’ Union and the new buildings at the Bank of England. The interview concludes with her admitting that the family home was a 1930s semi. ‘I don’t approve, of course, but I daren’t say anything or Daddy would be upset.’ Kristal finds the remark ironic, given her relations with her father, and indicative of the difficulty she faced in being taken seriously. It seems equally likely that the irony was deliberate and that Boty was playing on the reporter’s expectations of a posh bubbly blonde by delivering a quotable comment she knew would cause another explosion at the breakfast table if Albert, like many middle-class Conservatives, took the Express. But the Anti-Uglies had enemies closer to home. The Times might be expected to complain about their ‘lumpy coats, blue jeans … and, in one case, green boots’, but one of the group recalls that as they marched past Mary Quant’s new boutique, Bazaar, an ‘incredibly tall, elegant woman’ came out of the shop and said: ‘Oh but you’re all so ugly yourselves.’

Kristal’s close focus on the brief span of Boty’s life highlights the complexity of a period too often glossed simply as ‘The Sixties’. He also shows how small the scene was. Russell’s film for Monitor had to be prefaced by the presenter Huw Wheldon with a warning that viewers were about to see footage from ‘the world of Pop Art … of film stars. The Twist. Science fiction. Pop singers. A world that you can dismiss if you feel so inclined, of course, as being tawdry and second-rate.’ It was, as Peter Blake remarks, ‘incredibly patronising’, but Wheldon knew his audience. For every spellbound Mellor there were thousands of Albert Botys. The film got the worst ever audience rating for the series. Viewers reported themselves appalled at ‘the beatnik level of the world of art’, though some confessed to being reluctantly fascinated by an insight into a ‘disturbed and frightening world’. They weren’t entirely wrong. The world of NOW was bright and freewheeling but it was also disturbed and frightening, especially for women. The rejection of convention left them free but also vulnerable. Boty’s flamboyance, her willingness to talk about sex and to confront male aggression head-on, was at times successful. Carey remembered one of Boty’s fellow students asking insolently why she wore so much lipstick. ‘To kiss you with,’ she said, and ‘he fled.’ But her very existence, in its unapologetic vitality, was enough to provoke. The graphic designer Richard Hollis, a contemporary at Wimbledon, found her ‘over-lush, you could say. I don’t know if you’d call it pushy.’ Of her work he says: ‘It’s direct, energetic, and I think that’s how she was … Her work looks quite confident, which is what irritates me about it.’

Boty’s artistic response came in two of what Kristal considers her ‘most fully realised’ works, painted between 1963 and 1965: It’s a Man’s World I and II. In I the rows of heroic men, Proust and Elvis, Muhammad Ali and the Beatles, are grouped around an unfolding, vulval red rose. The only woman depicted is Jackie Kennedy in the open car, pink pillbox hat turned towards her husband as he clutches his throat. II is all women, soft-porn pin-ups surrounding a stark, full-frontal nude with pubic hair, all set against the landscape garden at Stourhead. Two sorts of nature ‘improved’ to suit a certain aesthetic, disrupted by a reality.

In The Sadeian Woman, published twelve years after Boty’s death, Angela Carter discusses ‘the blonde as clown’ and the violent compound of attraction and revulsion generated by ‘the unfortunate sorority of St Justine, whose most notable martyr is Marilyn Monroe’. Much of what Carter writes could be applied to Boty. Kristal’s interviews with her surviving friends are full of references, shocking in their casualness, to the violence that was the price of abandoning convention. Paula Nightingale, who shared a flat with Boty and another friend, got a message from the RCA to say her mother had rung to tell her she had burned all her paintings. ‘She was so upset’ that her daughter had left home. Nightingale remembers the other flatmate, Jane Percival, being depressed because of ‘something shattering’ that had happened to her. This, another RCA contemporary Nicola Wood confirms, was a rape. Wood too was raped by an ex-boyfriend and became pregnant, as did Boty during a brief relationship with the artist Nicholas Garland. Abortion was still illegal, risky and expensive. Boty and Garland scraped together the money but Garland, no longer in London, didn’t visit. ‘It’s one of the things in my life I feel bad about … I rang her … she never picked up.’ Her flatmates did see her in the clinic and Nightingale remembers it being ‘shocking’ to see her so pale: ‘This poor girl on her own and not able to tell her family.’

At the same time the career of Pauline Boty, artist, was taking flight. A few months after she graduated in 1961 her work featured in a four-artist exhibition at the AIA Gallery in Soho. She was moving away from stained glass, too cumbersome for the small-scale imagery that now interested her, via collage towards painting. There were influences such as Kurt Schwitters and Max Ernst that she shared with Blake and others, and more unusual enthusiasms too, including the graphic ‘collage novels’ of Norman Rubington and the work of Sonia Delaunay. Delaunay wasn’t much in fashion at the time, but the abstracted expanding circles of her paintings perhaps inspired Boty’s attempts to depict her orgasms, which she described as ‘orange circular shapes, streaming outward’. There were echoes of Surrealism. She told Ken Russell that she liked science fiction because it involved ‘something terrible and ridiculous at the same time’. The eruption of the frightening or monstrous into the normal was a theme that reflected her life as much as her artistic preferences. ‘I did some [pictures] at home and my mother … said: “To think I’ve got someone like that for a daughter!”’

Boty’s place in the much contested origin story of Pop Art is in some dispute. Who coined the term, on which side of the Atlantic the movement started and who was in it are issues to which Kristal, who brings the broader perspective of a New Yorker, sensibly pays only passing attention, suggesting that Pop ‘alchemised out of something in the air’ at different places at the same time. Boty’s work was shown under the Pop label from the beginning, and also featured in the shows New Art and New Approaches to the Figure in 1962, the same year as Pop Goes the Easel. Like most young artists needing money she had many jobs. As well as the usual waitressing, teaching and modelling there was some acting, the appearances on Ready Steady Go! and a fortnightly monologue on The Public Ear for the Light Programme. Her suede-coat voice, which struck more conservative listeners as ‘unattractive’, was heard in diatribes on subjects including English men, marriage and what she called ‘sex advertising’, especially as aimed at women. ‘Do you know what you’re buying when you buy your stockings, cigarettes, beer, chocolate, cars or petrol? Do you know you’re buying your dream?’

This was 1963, which Kristal describes as Boty’s ‘annus mirabilis’. She appeared on stage at the Royal Court, had her first solo show and, despite warning women listeners to The Public Ear that ‘the more we allow ourselves to think of marriage as the only aim in life, the more we allow ourselves to be slaves to domesticity,’ she got married. ‘I was rather surprised when I did it,’ she told Dunn, and many others were surprised too. She had known the literary agent Clive Goodwin for ten days and the wedding at Chelsea Register Office was kept secret from her parents, most of her friends and Philip Saville, the married man with whom she was having an affair. Opinions at the time and since have varied as to why she did it. She told Dunn that Goodwin made her laugh and was the only man who had ever accepted her ‘intellectually’. She also said that having a married lover was frustrating. ‘You’re kind of sitting in your little box of a room waiting for a phone call … and it’s lovely, you know, and then they put you safely back in your box and they go home to children or something like that … and it just got to a peak when I thought, “Well, this is just incredibly boring” and I happened to meet Clive.’

Kristal balances the various recollections. Saville, a television director described by his son as an ‘epic womaniser’, gave a self-serving account of a suspiciously well-constructed scene in which, having begun to find Boty tiresome ‘as she wanted a commitment’, he came home from rehearsals for Hamlet and, leaning towards his wife to kiss her, was slapped in the face and shown a telegram reading ‘BY THE TIME YOU READ THIS IS I WILL BE MARRIED TO CLIVE. PLEASE FORGIVE ME.’ The reader is more inclined to believe Boty’s sister-in-law Bridget, the most illuminating contributor to the Gazelli volume, who sees an element of desperation in the sudden move. ‘I think the other lot,’ Bridget says, meaning the London friends, ‘have got it just a bit wrong about what Pauline was like. I think she was quite a frightened person. She had a lot to be lonely or sad about.’ Boty’s fear, the sense of being trapped in a box, found expression in her identification with Marilyn Monroe, which intensified as press coverage continued to focus on her as what Men Only called ‘a pet, darling and symbol’ of Pop Art. In a profile of Boty the magazine cropped the nude photographs to leave out most of the paintings. Boshier said he had never seen her cry so much as when Marilyn died. What she called ‘the whole idea of hipsterism … being completely open all the time’ was becoming its own kind of trap, and convention, in the form of marriage, was a way out.

Goodwin was an activist on the left, editor of the radical magazine Black Dwarf, and Boty, as she began to move more in his literary and political circles, seemed to her old friends to be painting less. Whether she would have returned to art or persisted with acting, as she sometimes said she wanted to, is impossible to tell. In most people’s lives the early twenties are years of experiment. How fast things were changing in Boty’s life and in her mind is evident in the interview with Dunn. In the first session she said that she had never wanted children or a conventional family life. When she found herself pregnant she told Dunn that she wanted to add to the interview. ‘At first I was terrified,’ she said. She was afraid of losing her freedom, daunted by the thought of creating a new life. But then ‘everything in you works towards you wanting it … although it was an accident I’m secretly more pleased about it than I could ever admit.’ That was June 1965 and although the pregnancy proceeded normally, tests revealed abnormalities, leading to a diagnosis of thymoma, a rare but dangerous cancer once metastasised. Treatment would necessitate aborting the pregnancy and this Boty declined to do. Kristal has a chapter on ‘Pauline’s choice’ in which he weighs the reasons for it and the conflicting memories and opinions of her friends. Perhaps it was the horror of the first abortion, the lingering effect of a Catholic upbringing, the fact that treatment might not work and that even if it did, radiotherapy would make her infertile. No doubt these were factors but the drive towards maternity that she described to Dunn was perhaps decisive. Her daughter, Boty Goodwin, was born on 12 February 1966, then after a few days sent to Pauline’s parents so that the treatment could begin. It was unsuccessful and on 1 July she died. Her husband had found it difficult to visit her in her last days and it was Albert who registered her death. Under ‘Occupation’ he entered: ‘Wife of Clive Goodwin a Literary Agent’, one last victory for Carshalton values.

Boty’s story in itself is poignant. What followed became more like Jacobean tragedy. Goodwin’s career flourished. Though he was shattered by the loss of his wife he threw himself into his work, expanding the film and TV side of the agency while continuing with his activism, investing in The Rocky Horror Show and keeping Black Dwarf afloat. In 1977 he went to Hollywood to put together his biggest film deal to date. Reds, directed by and starring Warren Beatty, is the story of the American journalist John Reed, who was radicalised by his coverage of the Bolshevik Revolution. While in Los Angeles Goodwin suffered a brain haemorrhage in the lobby of the Beverly Wilshire hotel. The hotel called the police, telling them he was drunk. Left in the drunk tank he died in the night. Tony Garnett lodged a wrongful death complaint on behalf of Goodwin’s 11-year-old daughter. Beatty supported the case with his own lawyers and gave evidence to the effect that Goodwin was on the cusp of major financial success. In 1983 a substantial settlement was reached, enabling Boty to buy a flat in London.

Young, wealthy and isolated, Boty floundered somewhat. Her upbringing had been disjointed, spent between her grandparents, who called her ‘Katy’ and had never understood Pauline, and Clive, who couldn’t bear to talk about her. Boty was good-looking, though in a different style from her mother, with red hair and a round face. She was talented but also, according to an early friend, unsurprisingly ‘quite compartmentalised’. One of the compartments was heroin. Boty’s adult life was spent between London and Los Angeles, where she enrolled to study painting at CalArts. The drugs got worse, but after the visit to England during which her mother’s paintings emerged, thanks to Bridget, from store in Albert’s bungalow and were shown to Mellor, Boty stopped using. ‘She was very, very proud,’ Abigail Thaw remembers, ‘excited that her mother’s paintings were going to have some kind of recognition.’ Back at CalArts she enrolled in a postgraduate creative writing course and was off heroin. On 10 November 1995, she gave her graduation presentation. It went well and afterwards she ‘chose to reward herself’, as Kristal puts it, with a few drugs and to stay in her studio overnight. Her body was found there three days later. Accident, suicide or, as Kristal suggests, bad luck: ‘She rolled the dice and came up snake eyes.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.