According to the Mahabharata, the legendary city of Indraprastha was founded by the five Pandava brothers for their queen, Draupadi. Its wide streets and orchards surrounded a palatial hall, built by the demon-architect Maya, which appeared ‘like a mass of new clouds conspicuous in the sky’. The hall was ‘so rich and well built’ that it rivalled the celestial home of Brahma. Its columns and arches were inlaid with jewels, and its golden walls were ‘adorned with many varied pictures’. It also contained many artful illusions: a crystal floor that looked like a lotus pond, set with flowers cut from gemstones; and a real pool so clear and still it appeared to be solid stone. There were doors that looked like walls, and walls that looked like doorways. In the Mahabharata, these tricks infuriate the rival cousins of the Pandavas, setting in motion a plot to steal the kingdom and, eventually, an apocalyptic battle on the field of Kurukshetra.

Last year, newspapers reported that the Archaeological Survey of India, a government agency, was about to unearth the ruins of Indraprastha in New Delhi. I’d heard the story before. In early 2014, the Hindu reported that an ASI excavation would ‘conclusively prove the existence [of] the city of Pandavas’ in the capital; in April that year, the public was invited to watch the dig in progress. It was a fine day before the heat of summer. The dig was taking place in the grounds of a fortress built during the reign of the second Mughal emperor, Humayun, in the mid-16th century. The western gateway and walls of the Purana Qila (which means ‘old fort’) stand on high ground: Indraprastha was apparently somewhere deep beneath them.

I joined the crowd that thronged through the main gate and past the magnificent library tower from which Humayun is said to have tumbled to his death. In a corner of the fort, where a bare slope pitched into a shallow ravine, a grid of descending squares had been dug into the soil. They revealed eight distinct historical strata. The topmost was Mughal, followed by deposits from Sultanate and Rajput settlements, then below them the post-Gupta kings, the Guptas, the Kushans and (preceding the common era) the Sungas and the Mauryas. Each layer had already yielded a small treasure of toys, idols, beads and weaponry as well as structural remains – a continuous chain of human habitation reaching back to the fourth century BCE.

There was no stratum, however, belonging to Indraprastha. A few stray shards of grey pottery, some decorated with fine strokes or circular patterns, were the only evidence of the epic age. This is Painted Grey Ware, or PGW, which dates to the centuries around 1000 BCE. But there was nothing else to mark a historical layer: no jewellery, no evidence of building, no burial grounds. We scoffed and shook our heads at the anticlimax, pocketing pieces of discarded terracotta as we left and joking that we were carrying off fragments of Pandava dinner plates.

But I didn’t scoff last summer when I read that the ASI was renewing its efforts. New Delhi was being transformed, both in its architecture and its political character. A new parliament building had been inaugurated in May. The Central Vista, the axis of the British imperial capital, was being reconstructed at vast expense. The exhibition complex across the street from the Purana Qila had been razed and rebuilt as the venue for the 2023 G20 Summit. As the climax of India’s tenure as host nation, September’s meeting of heads of state was presented to Indians as the height of national revival and as a celebration of Modi’s emergence as a world leader.

One measure of the pomp and vanity of the summit was that Indraprastha only qualified as a sideshow. Foreign leaders would be offered a tour of the dig, the newspapers said, and be given a glimpse of our glorious antiquity. ‘The excavation is not specifically for G20,’ the supervising archaeologist, Vasant Swarnkar, told reporters. ‘But the findings will be showcased to all incoming delegates.’ Locating Indraprastha here would subvert Delhi’s visible origins as a city built by sultans and emperors in the Islamic period, between the 13th and 18th centuries. Most of the city’s forts, tombs, stepwells and prayer places date from this period – a source of much resentment for Hindu nationalists. And it would give Modi’s modern Hindu state an ancient Hindu progenitor in India’s capital.

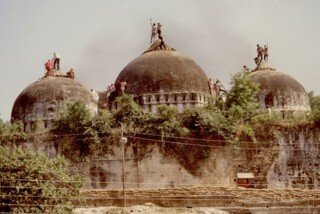

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) knows the propaganda value of historic sites, real or imagined. Its popularity burgeoned in the 1990s, following its campaign to demolish a Mughal-era mosque in the city of Ayodhya. The mosque was dedicated to Humayun’s father, Babur, but was suspected of having been built on the ruins of a sacked temple. Some Hindus regarded the site as the birthplace of Rama, the divine hero of the other great Sanskrit epic, the Ramayana. On the back of a truck outfitted as a chariot, the BJP’s co-founder Lal Krishna Advani took a cross-country tour whipping up Hindu sentiment before arriving in Ayodhya. In 1992, in defiance of the Supreme Court, a mob was set on the Babri mosque and tore it down.

Last August, in a speech marking Indian Independence Day, Modi referred to the ‘thousand years of slavery’ Indians had endured and promised that a new millennium had begun. The BJP has long pushed a revisionist history of India, cleanly split between an ancient past of righteous Hindu kings and a more recent age of foreign oppression. In this account – inherited from early colonial philologists and historians such as William Jones and James Mill – the subcontinent had belonged since prehistoric times to one continuous, indigenous Vedic civilisation, shattered in 1192 by the first Islamic invasions.

To its sympathisers, the new government is correcting the false narrative enforced by the Nehruvian establishment and Marxist academy. Hindus are encouraged to look around and see only the desolation of their ancient heritage. ‘Only now are the people beginning to understand that there has been a great vandalising of India,’ V.S. Naipaul told an interviewer after the demolition of the Babri mosque. ‘What is happening in India is a mighty creative process.’

So far the creative process has resulted in a lot of costly and grandiose construction projects. The world’s tallest statue was erected in 2018 in Gujarat, Modi’s home state. Vallabhbhai Patel, India’s first home minister and the person credited with consolidating the union after 1947, stands a hundred times larger than life and twice as tall as the Statue of Liberty. The apotheosis of the BJP’s monument-building is the new temple in Ayodhya built over the ruins of the Babri mosque. On 22 January, the ritual to consecrate the idol of Rama there was performed by Modi himself.

It was a Muslim writer who left the earliest record identifying the Purana Qila with the site of Indraprastha. ‘Delhi is one of the greatest cities of antiquity,’ Abul Fazl wrote in the Ain-i-Akbari, his contemporaneous chronicle of the court of Akbar, Humayun’s son. After describing the previous cities of the Delhi sultans, he praises Humayun for ‘restoring the citadel of Indrapat and naming it Dinpanah’ – sanctuary of the faith. To Fazl, the Mahabharata was ‘the work of wise sages’ and he called up the ancient history of the site to lend an aura of power to his own king’s line.

In later centuries, British writers and monarchs shared this view of the place’s significance. In 1911, George V announced ‘the transfer of the seat of the Government of India from Calcutta to the ancient capital, Delhi’. The architects of the new city aligned the Central Vista with the viceroy’s mansion at the top and Purana Qila at the far end. The fortress had by this time fallen into ruin and was occupied by a farming community, whose members referred to it as ‘Indarpat’. The name was faithfully recorded in surveys, heritage listings and revenue records. As the historian Mrinalini Rajagopalan puts it, ‘the affective projection of Indraprastha’ was turned into ‘archival fact’.

It wasn’t until 1954 that archaeologists became involved. A series of excavations at sites associated with the Mahabharata found at their lowest levels a common, archaic layer of Painted Grey Ware. The theory was born that PGW represented the material culture of ‘the Mahabharata period’. Just as Heinrich Schliemann had ended speculation about the Iliad by discovering Troy, Indian archaeologists claimed to have found traces of the world of the Mahabharata kings in present-day Tilpat, Hastinapur and Kurukshetra. Only Indraprastha left them wanting. The few PGW finds at Purana Qila were ‘unstratified’, isolated fragments that might have come from somewhere else. Work on the site stopped in 1973.

Last July, I visited the ASI’s latest excavation in the centre of the fortress. Monsoon downpours had flooded the excavation trench, which was covered with a yellow tarp. The work persisted, humid and desultory. A worker in his undershirt split lengths of bamboo pole, to be woven into the roof of a frame above the site. As I crossed the lawn towards it, a nervous young archaeologist called out: ‘We can’t tell you anything!’

Eventually I met the superintending archaeologist, Swarnkar, at his ASI office. He expressed reasoned confidence in the Indraprastha theory. ‘Through India’s historical chronology, every culture, it’s here,’ he said of Purana Qila. ‘It’s been continuous, there’s no break. Why did everyone settle in this particular area? Something was built here that was important.’

Swarnkar was responsible for reviving the excavation in 2014, a few months before Modi was elected. ‘People assumed they [the government] would be interested,’ Swarnkar told me, choosing his words carefully. Instead, he was twice posted away from Delhi, and both times his team was dispersed and their fieldwork halted. Last September, the G20 Summit came and went with no epic find. The archaeologists had reached as far as the Kushana level, still centuries from the PGW horizon, when they were forced to wrap up. Swarnkar was frustrated – about how much it had rained, about the egregious red tape and the inadequacy of his equipment. When his team asked for tin sheets to cover the trench they were refused, and had to scavenge bamboo poles and tarps. The tarps sagged and then split in the rain. Swarnkar showed me a picture on his phone of a man standing in the bottom of the trench, raising a bucket over his head and bailing water out of the excavation they had made with painstaking brush and trowel work. ‘That hurt the heart,’ he said.

Indraprastha, if it’s ever found, won’t be a city. As far as we can tell, PGW was produced by a tribal society, who cleared the jungle to build basic settlements. They had no writing or currency, so Swarnkar doesn’t expect to find epigraphic evidence to identify the settlement by name. The most that could be claimed, he told me, is that ‘there was activity here in the period of the Mahabharata. We cannot claim that this is Indraprastha.’

In 1946, surveying the strained efforts to reconcile the Iliad’s account of Troy with the site of Hisarlik, Rhys Carpenter wrote: ‘We are left with the uncomfortable suspicion that there is something wrong either with Schliemann’s Troy or with Homer’s, and that there is nothing much to be done about it.’ His coda: ‘Homer did not dig.’ The same is true of those who compiled the Mahabharata. They were recounting their ancient past, events almost as far removed from them as they are from us. The descriptions of courtly life and total war were descriptions of their own era, between 300 BCE and 300 CE, not of the period when the epic events took place.

The comparison of Indraprastha to Troy would be more apt if Greeks still worshipped Apollo. The principal figures of the Sanskrit epics, among them Rama and Krishna, are still the most prominent Hindu gods. The imagery we associate with them has been shaped by technology: since the 19th century, lithography, offset printing, television and movies have glorified the Ramayana and Mahabharata. In the late 1980s, as Wendy Doniger noted, ‘the streets of India were empty (or as empty as anything ever is in India) during the broadcast hours’ of B.R. Chopra’s Mahabharata TV series.* Its scriptwriter was an Indian Muslim, Rahi Masoom Raza.

In 2016 the Ministry of Culture sponsored the first Indraprastha Festival, along with an international conference. Indraprastha Revisited, a collection of the conference proceedings, includes an architect’s proposal for a reconstruction of Indraprastha inside the Purana Qila. At its centre is a vast circular hall – Maya’s hall – with six satellite buildings, each nearly the size of Humayun’s tower. Beyond the palace are blocks of buildings, their purpose unclear, packing the fortress from wall to wall. The architect, Renu Khanna, writes that the plan was drawn up using only the poem’s evocation of Indraprastha, ‘not through any archaeological evidence’. Yet her wish is that ‘Indraprastha moves from mythology to history,’ remaining ‘in the hearts of the people for time immemorial’. Moving the Sanskrit epics ‘from mythology to history’ turns out to mean the obliteration of an archaeological site by a construction site. This is the kind of historical reckoning which India’s present government endorses. A point rarely noted about Ayodhya is that the BJP didn’t campaign to excavate the temple they were seeking, only to build on top of it as quickly as possible.

Meanwhile, in a small museum built into the arcades of the Purana Qila, other finds from the site sit in their vitrines, overshadowed by the ersatz fantasy of what came before. The finds include relics from ancient and medieval Hindu kingdoms – a spoked copper wheel and ivory amulet of the Kushanas, a Gupta-era plaque of the goddess Gaja Lakshmi – and number in their thousands. There are seals and sealings, beads of jasper, carnelian, amethyst, ivory and bone; clues to the people who lived on this site across thousands of years. The sense of so many periods immanent in a single spot calls to mind Jawaharlal Nehru’s description of India: ‘Like some ancient palimpsest, on which layer upon layer of thought and reverie had been inscribed, and yet no succeeding layer had completely hidden or erased what had been written previously.’ The Purana Qila and the ground beneath it affirm the fraying idea of the country as a palimpsest. It’s not the archaeologists we have to worry about, but the architects.

Swarnkar’s most treasured find is a ring-well from the Mauryan period (322-185 BCE). It’s made of eighteen terracotta rings, one inside the other, forming a two-metre tube that he believes would have collected clean groundwater. In the same stratum of the dig, he found long bones and parts of a horse’s skull lying on a fire altar: an arrangement that suggests to him an Ashwamedha, the Vedic horse sacrifice. His own proposal for an open-air museum, with a glass-topped walkway covering the original excavation site, has got nowhere.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.