The only reason Werner Herzog hasn’t yet made a film about the Ancient Mariner may be that, having already inadvertently incorporated so many elements of the poem into his own work, he has become him. Herzog certainly shares Coleridge’s interest in the physical and spiritual toll taken by epic voyages into uncharted waters. There are several rafts as well as a phantom schooner stuck up a tree in Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), the film about a berserk conquistador which established him as a leading figure in German New Wave cinema; and a steamboat hauled over the isthmus separating two tributaries of the Amazon, and then flushed down a flight of rapids, in Fitzcarraldo (1982), the film about a 19th-century rubber baron and opera fanatic which sealed his international reputation. Boats carrying a cargo of corpses drift lazily into view towards the end of ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ and of Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), Herzog’s elegantly inventive homage to 1920s German Expressionist cinema.

Like Coleridge, too, Herzog has an eye for spectral landscape. The Mariner’s journey to the edge of the Antarctic, a land of ‘mist and snow’ where ‘ice, mast-high, came floating by,/As green as emerald,’ finds several echoes in Encounters at the End of the World (2007), his Oscar-nominated documentary about the ‘dreamers and scientists’ employed at the US Antarctic Programme’s McMurdo Station, on Ross Island. Herzog, for whom nature is an obscenity, a squalid turmoil in which life-forms flourish briefly in order to kill or be killed before, as he puts it, ‘just rotting away’, reserves an especial distaste for the ‘sheer hell’ of underwater existence. He has perhaps seen what the Ancient Mariner saw from the deck of his ship: ‘The very deep did rot … Yea, slimy things did crawl with legs/Upon the slimy sea.’ I don’t think he’d mind too much if his films were to leave their audience in a state similar to that of the Wedding Guest to whom the Mariner tells his tale. ‘He went like one that hath been stunned,/And is of sense forlorn.’

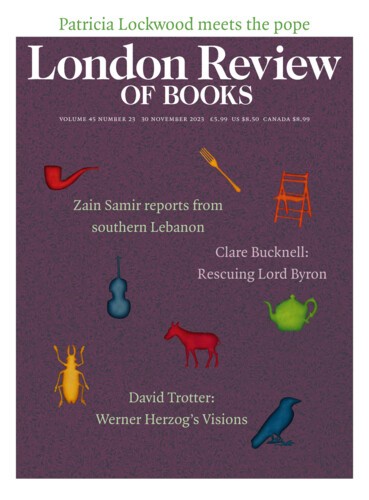

These days Wedding Guests are easier to come by. Herzog has always steered well clear of social media, but he’s a veteran of the festival circuit, the TV studio and, more recently, the podcast couch. His website describes him as the director of ‘more than sixty’ films; in fact, it’s more than seventy. And we need to add the 23 operas he has staged (Mozart, Beethoven, Verdi, a lot of Wagner). What’s striking about this back catalogue, apart from its sheer size, is the degree of curation it has involved. There’s a flame to be kept alive. Herzog must be one of the few directors to provide all the commentaries on the DVD versions of his own films. He’s a provocative, erudite interviewee, live and on the page. The image on the front cover of the most substantial collection, Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed, edited by Paul Cronin, somehow contrives (it’s not Photoshopped) to pair an implacable-looking Herzog with a grizzly bear standing on its hind legs, jaws agape. Be, if not afraid, then just a little abashed. In the preface to the 2014 edition of the Guide, Cronin observes that fifteen years before, when he first started to pull these interviews together, Herzog had not yet ‘attained the godlike status the world now accords him’. The internet has paid its ambiguous respects by converting his distinctive voice – already a fixture on The Simpsons – into a meme. Have a look at the YouTube videos in which an imitation Herzog narrates well-known children’s stories like Madeline and Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel as though they were updates on the Book of Job.

The flame to be kept alive is the doctrine of ‘ecstatic truth’ that Herzog first fully articulated at the end of the 1990s as an attempt to explain his extreme dissatisfaction with cinema vérité. Film – fiction or documentary – should not concern itself with the facts of ordinary existence, which are the province of the journalist, the bureaucrat and the accountant. ‘Facts don’t illuminate,’ Herzog explained to Cronin. ‘Only truth illuminates. By making a clear distinction between “fact” and “truth”, I penetrate a deeper stratum that most films don’t even know exists.’ Herzog’s primary characteristic as a filmmaker is his willingness to scan the horizon for the faintest sign of a filmable event. This unquenchable intellectual curiosity is, however, accompanied by an almost complete incuriosity about what it is in our equipment as human beings that enables some of us, at least, to recognise an ecstatic truth when we see one. Nor has Herzog taken the trouble to define his version of the doctrine against those put forward by its several ancient exponents and their innumerable modern avatars. We’re left guessing. There might be a clue in the final stanza of Friedrich Hölderlin’s ‘Lebenslauf’ (‘The Course of Life’): ‘The gods say: let man test everything/So that, powerfully nourished, he’ll learn to be thankful/For all and realise his freedom/To set out wheresoever he choose.’ I’m quoting from Nick Hoff’s translation of the Odes and Elegies, for which Herzog supplied an enthusiastic blurb. The reason most films choose to remain unaware of these deeper strata may be that some of them, at least, are already well-trodden ground.

Curation has a tendency to reiterate rather than expound. Herzog certainly does like to double down. When Lessons of Darkness, his film about the aftermath of the First Gulf War, was shown at the Berlin Film Festival in 1992, it caused a minor riot. Sequences of sumptuous shots which travel over the Kuwaiti oilfields set ablaze by Saddam Hussein’s retreating army represent ecstatic truth at full visionary throttle. But we’re never told that we’re in Kuwait. Herzog’s mesmerising tour of hell elides any attempt to understand the causes of the war or assess responsibility for its outcome. After the screening, Herzog was to recall, the two thousand people in the audience ‘rose up with a single voice in an angry roar’ to denounce him for aestheticising the evidence of destruction. Relishing the palpable hostility, he proceeded to claim Dante, Goya, Breughel and Bosch as his models, before concluding with the observation that ‘You cretins are all wrong.’

That was a long time ago, but testiness remains in his repertoire. To ‘pedantic theoreticians’ scanning Bad Lieutenant (2009) for references to Abel Ferrara’s film of the same name, he had a simple message: ‘Go for it, losers.’ ‘You have to brace yourself for the bozos,’ he told an audience at the BFI in 2016. The bracing goes on. The title of his new memoir presents him as a modern-day Thomas Hobbes come to demonstrate, in as disobliging a manner as possible, that human existence tends to the nasty, brutish and short. What’s more, it is itself a reiteration. Every Man for Himself, and God against All was the original title of one of Herzog’s best-known films, subsequently released in America as The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974). So here he is, nearly fifty years later, at the age of 81, still giving it large.

Herzog is a skilful raconteur, and the narrative of his life bowls along at a lick, anecdote spawning anecdote. A good number of these will be familiar to anyone who’s had any contact at all with the Wernerverse, but there’s plenty of informative background detail, especially concerning his early years. Herzog was born on 5 September 1942 in Munich. His mother, Elisabeth Stipetić, relayed the exciting news to his paternal grandfather, Rudolf Herzog, the patriarch of the family, but not to her husband, Dietrich, who was serving in the army in France (and probably, since he ‘knew how to make himself scarce’, well to its rear). Both men were academics: Rudolf a classics professor turned archaeologist who made significant discoveries on the island of Kos; Dietrich, more ‘pirate’ than professor, a perma-tanned jack of all intellectual trades replete with duelling scars, and an enthusiastic Nazi to boot. The parents separated soon after the war, and it’s pretty clear whose side the son is on: Dietrich and his contemporaries were a ‘waste’, he says, a generation lost to fascism and inertia. Elisabeth, who came from an Austro-Croatian family of administrators and army officers, trained as a biologist under the future Nobel laureate Karl von Frisch. To escape the bombing, she took Werner and his brother, Till, up into the mountains, to the remote village of Sachrang on the Austrian border. We learn a lot about life in Sachrang, about the family’s return to Munich after the end of the war, about expeditions to Africa and America. Well-travelled barely does justice to a man whose ‘Wanderjahre’ appear to have begun in his mid-teens, and not yet to have ended.

Somewhere in the middle of all this, films began to be made. ‘I learned the basics about cinema in about a week from reading the thirty or forty pages on radio, film and TV in an encyclopedia. I still think that’s about all there is to know.’ By the age of 21, Herzog had his own production company. There’s more to come in the memoir about family, but not much. Wives and children find themselves parcelled up together into a single, shortish chapter. Wives and children, we gather, are not the stuff of ecstatic truth. ‘I almost always had helpers, family, women,’ Herzog declares in his foreword. ‘With a very few exceptions, this book is not about them.’

Herzog has long proclaimed his affection for the Oxford English Dictionary, and while browsing in it he may conceivably have dwelt on the original meaning of the term ‘projector’: someone who ‘plans or designs an enterprise or undertaking; a proposer or founder of some venture’. He has always been a maker of projects rather than films: that is, of projects whose primary but by no means only expression is a film. Fitzcarraldo, the most demanding of them all, is a film about a project. Carlos Fermín Fitzcarrald López (1862-97), the opera-loving rubber baron, once got a boat across an isthmus by having it taken apart on one side and reassembled on the other. Herzog’s fascination with the methods used to transport and erect the huge stones at Carnac gave him a more exciting idea: rather than dismantle the damn thing, use a system of ropes and turnstiles to manoeuvre it up and over the intervening hill. At one point, he began to wonder if he should play Fitzcarraldo, because the task (Aufgabe) set by his Carnac obsession had turned the film’s protagonist into a version of himself. Forty years after its release, he remains a student of prehistoric technologies. ‘I pursue the progress of the research with curiosity, ready at any time to revise my ideas.’ The longest chapter in Every Man is the one devoted to ‘Unrealised Projects’, of which there are a large number. It all makes for an interesting selection of Wedding Guests. ‘I receive regular invitations from the community of particle physicists who admire my films as much as rock musicians, skateboarders and various other enthusiastic denominations do.’

Herzog likes to insist that a director should be more of an athlete than an aesthete and, perhaps as a result, the memoir devotes a great deal of attention to the human body in states of distress and disrepair. I soon lost count of all the many injuries and diseases (‘My shit was bloody froth’) endured in pursuit of ecstatic truth. Damage is evidently the price to be paid for projecting. But there’s more to this chronicle of fractures and abscesses than exposure to accident as a professional hazard. Every Man is in its self-mythologising way the record of a charmed life. The tarantula Herzog once found asleep in one of his shoes and the giant scorpion which spent the night under him in a hammock both declined, for reasons best known to themselves, to put an end to him. A plane on which he has a seat booked leaves without him and promptly crashes into a mountain. He turns down a group invitation to meet a senior guerrilla commander; those who attend are summarily executed. Herzog has become a virtuoso of the near miss. Watch on YouTube as the bullet he doesn’t quite dodge while being interviewed on the streets of Los Angeles barely grazes him.

The projector may in undertaking his ventures have left family and friends behind him, but he rarely operates alone. There’s an understanding among those who share his ‘hunger for transcendence’ that ensures a measure of moral support at the very least, and often a great deal more. Herzog’s childhood desire to fly – ‘by myself, with my body, without any gear’ – soon found an inspiration and model in the Swiss ski jumper Walter Steiner, whose talent he claims to have spotted from the first. ‘This quiet young man had something ecstatic in the way he flew, though technically he still had flaws … His element seemed to be the air, not the earth.’ In 1972 Steiner won gold at the Olympic Games in Sapporo and the World Championships in Planica. In 1974 Herzog made a film about him which expresses the ‘immediate kinship’ the two men had felt with each other. Then there’s Bruce Chatwin, whose leather rucksack Herzog inherited, and apparently still uses; and the Indochina veteran and photojournalist Denis Reichle (it was he who squashed the scorpion groggily exiting the hammock); and Werner Janoud, ‘completely primal and self-made, the only person I know who is absolutely and totally not deformed by human society’. These are the ecstatic truth bros. Herzog’s more recent Hollywood career (he played the villain in the first Jack Reacher movie) has brought him into contact with legends of a different sort. ‘Tom Cruise was extremely respectful to me. For my part, I was impressed by his absolute professionalism.’ The Ancient Mariner seems about to embark on a victory lap.

That’s not at all what Coleridge had in mind for his poem’s protagonist, whose guilt at the wanton slaughter of a blameless bird seems likely to keep him on the road for some time yet. Every Man does in fact explicitly raise the topic of guilt in relation to an albatross of a kind: Klaus Kinski, the leading man in five of the fiction films (Aguirre, Fitzcarraldo, Nosferatu, Woyzeck, Cobra Verde). Herzog was in his early teens when he first met Kinski, then 26 and already well launched on a career as a ‘misunderstood starving genius’. Kinski had the use of a back room in the pension in the Schwabing district of Munich where Herzog lived with Elisabeth, Till and his half-brother, Lucki Stipetić. He apparently lost no opportunity to abuse or assault his landlady and fellow lodgers, before eventually being kicked out for trashing the bathroom. This crisis constituted a rite of passage. ‘I know that, aside from my mother, I was the one who was not afraid of him. To me, he was a force of nature.’

Herzog’s task as a director was, as he once put it, to shape the ‘craziness’ inside this force of nature into form. Kinski became integral to Herzog’s most ambitious projects, his screen presence appearing somehow to incarnate rather than merely inhabit the character he was playing: successively maniac, dreamer, vampire, misfit, and maniac again. ‘No one,’ Herzog observed, ‘tamed him as well as I did.’ Like My Best Fiend, the documentary he made about Kinski in 1999, Every Man ends its account of their relationship on a note of reconciliation – ‘we had times of deep comradeship’ – after a long and often bitter struggle. ‘I was always prepared at any moment,’ he remarks of the making of Fitzcarraldo, during which the two comrades fought incessantly, ‘to confront anyone and everyone, whatever work and life threw my way.’

In 2013 Kinski’s daughter Pola, who was born in 1952, published a memoir, Kindermund, in which she describes in harrowing detail the sexual abuse she suffered at the hands of her father (‘Babbo’) between the ages of five and nineteen. ‘Pola – like a number of young women lately – had asked me for advice and support before she published her book,’ Herzog reports in Every Man. ‘I have absolutely no doubt about her account.’ Does that mean, he goes on, that he should ‘withdraw’ the films he made with Kinski? His answer is a series of further questions. Should we cancel Caravaggio because he killed someone in a brawl, or Wagner because he was an antisemite? It’s a slippery slope. But you can be against cancellation and still feel that what Kinski did requires a fuller reckoning than the sort of attribution of exalted status Pola must have heard often enough in her earlier years, and quite possibly understood as an incentive to remain silent. In November 1991, Pola’s mother, Gislinde Kühlbeck, called to tell her that Babbo was dead. ‘Ah, I can’t be angry with him,’ she remembers Gislinde saying. ‘He was a brilliant mind!’ Pola hung up.

Herzog has in the past proved an eloquent witness to the extent of the violence of which Kinski was capable. In Every Man, he describes Kinski’s arrival in the Urubamba Valley in Peru, where the opening scene of Aguirre was to be shot. After a couple of wet nights under canvas and a succession of tantrums, there seemed to be no alternative but to put him up in the only nearby hotel; where, however, his ‘rampaging’ continued. ‘The maniac hit out at his fleeing Vietnamese wife and drove her down the stairs in front of him.’ There’s a fuller account of this episode in Conquest of the Useless, the journal Herzog kept between June 1979 and November 1981 of the endlessly troubled production in similar locations of Fitzcarraldo. The entry for 19 August 1979 records a conversation with Walter Saxer, the producer of both films, during which the two men reminisce about the making of Aguirre. Herzog is reminded that ‘night after night’ Kinski would fly into a rage and drag his ‘Vietnamese wife’ through the hotel corridors, hurling her against the walls. The hotel-keeper had to be bribed not to throw him out. ‘Walter described how every morning at four he went around discreetly scrubbing off the splatters of blood (‘Blutspuren’) that the madman’s poor wife had left on the walls. Yet these were minor rites. To this day I have not dared to write down anything about those events.’ Herzog is no stranger to hyperbole, so it’s difficult to know exactly what happened. But it does look as though the man who prides himself on his ability to confront anything ‘work and life’ might throw in his way has admitted to a degree of complicity in what were by his own account sickening acts of violence. Minhoi Geneviève Loanic, the ‘Vietnamese wife’, had a child by Kinski and divorced him in 1979.

Conquest includes in the entry for 28 to 30 June 1981 a further revealing commentary on the damage done by Kinski’s manias. He was threatening yet again to bring the whole production down around him. ‘I listened to him unmoved, although I knew what a trail of destruction he has left behind him in his life.’ Kinski, Herzog notes, ‘did not give a fig for the laws’. ‘Then he described, as a threat to me, what he had done to his two daughters, Pola and Nastassja: for that alone, he would in the USA have got twenty years in jail.’ By this stage, Herzog had little reason to believe a word Kinski said, because the aim of his tantrums was evidently to intimidate rather than to inform. All the same, Kinski was now confessing to a crime so despicable that it would if proven have landed him in prison. His constant refrain to Pola had been that, while what he did to her was the ‘most natural thing in the world’, she must nonetheless never tell anyone about it. ‘Never, or I’ll end up in jail!’ In January 2013, Nastassja Kinski told Bild am Sonntag that while Kinski had ‘always touched me way too much’, she’d been able to prevent him from going any further.

Kinski has always loomed large in Herzog’s self-mythologisation. But he only ever appeared in a handful of the films. The doctrine of ecstatic truth is, by contrast, pervasive. There are further questions to be asked – even or especially in the absence of its malevolent talisman – of the broader premise on which it is based. Documentary has customarily been regarded as a genre duty-bound to deal in facts. But the only duty Herzog has ever felt as a filmmaker is, as he puts it, to ‘follow a grand vision’. His talent as an inquirer, backed by monumental self-confidence, has gained him access to sealed locations as disparate as death row and a cave full of prehistoric animal paintings. You sometimes wish that he’d handed his grand vision in at the door. It’s disconcerting that when he introduces the idea of ecstatic truth into Every Man, he does so in order to associate it closely with the way in which ‘fake news’ (his term), if repeated often enough and acted on, can ‘evolve’ into or assume the ‘structure’ of a fact.

One of my regrets about the memoir is that it barely touches on the friendship Herzog maintained with Fini Straubinger, the 56-year-old disability campaigner who features in Land of Silence and Darkness (1971). Straubinger lost both sight and hearing as a teenager, and for decades thereafter suffered from a debilitating addiction to painkillers. Herzog became her constant ally and companion in mischief. At the beginning of the film, Straubinger tries to explain the strange freedom she claims to feel in her solitude by recalling the ecstasy she saw on the faces of the ski jumpers she used to watch as a child. Herzog cuts to three successive shots of jumpers taking off or in mid-flight, tilted forward over their skis, mouths open in a kind of astonishment. It turns out that Straubinger had never been anywhere near a ski slope in her life. The words she utters are Herzog’s, as, I think, is the ecstasy they articulate. When she later speaks for herself, it is to describe – to emphasise – the ‘furchtbare Einsamkeit’ (‘terrible loneliness’) of the lives the deaf-blind have no choice but to live. What we witness, as we observe her daily routine, is the vivid sense of a blissful momentary release from solitude engendered by human contact. If there’s any ecstasy, here, it lies in the technique of tactile translation the deaf-blind use to communicate with each other and with their carers: rapid sequences of dots and dashes deftly etched on the palm and fingers of a hand. Such bliss reinforces, and is itself in turn reinforced by, the intervening solitude.

Herzog first met Straubinger when researching a documentary on the provision of facilities for the disabled. The film they subsequently made together is a stirring testament to her courageous efforts to mobilise support for fellow-sufferers throughout Bavaria. Images of ecstatic flight pale into insignificance by comparison with the love Straubinger shows towards the guests – each accompanied, in small blizzards of signalling, by a carer – at her 56th birthday party. In the memoir, Herzog describes Land of Silence and Darkness as his ‘deepest’ film. Its depth lies in the generous, precise attention it gives to the workings, for better as well as worse, of the ‘human society’ so despised by the ecstatic truth bro. This is the Herzog crux: that a filmmaker able as few others are to sense and grasp the uniqueness of what is happening in front of his own eyes should have expended so much effort in recycling the more ornate elements of Romanticism’s extensive detritus. I doubt there’s anything in his copious meditations on the obscenity of nature to match Delacroix’s Wild Horse Felled by a Tiger (1828).

In complete contradiction of the propaganda accompanying them, Herzog’s fiction films share with his documentaries a tendency to belie their often asserted reluctance to let an event speak for itself. In a fiction film, of course, everything is the stylised product of a grand vision. The obstacle to vision, in this case, is narrative, which if not necessarily productive of ‘facts’ is nonetheless prone to rely on a certain mundane logic, a bureaucratic calculus of cause and effect. So Herzog resorts to a further distinction, between its ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ manifestations. In Aguirre, for example, after the dramatic opening sequence of a baggage train in hectic descent from a mountain peak, he cuts to a shot, held for at least a minute, of the raging waters of the Río Urubamba in the valley below. Three seconds of this would ordinarily have been enough, he has explained, to set a scene; the point of dwelling on an image of turbulent chaos is instead to prepare the audience for the enormity of what is to come. Such ‘frozen moments’ don’t advance the action. Instead they connect ‘more deeply’ to an ‘inner narrative’. The film ‘almost holds its breath as the multiple threads of a story moving in all directions are tied in a knot for one brief moment’. The function of the knot-tying is to figure ecstatic truth.

We could say that the Herzog formula involves two kinds of breathing: no breath at all, as the knot of ecstatic truth is tied in the film’s depths; and a series of often rather laboured gasps for air as its outer narrative seeks to establish the encompassing rigidity of social and cultural norms. Fitzcarraldo the film amounts to a very long wait for Fitzcarraldo the project to begin: ninety minutes elapse before anyone makes any attempt to imagine how they might actually get the boat over the hill. Several of the intervening scenes would not have been out of place in a spaghetti Western: Kinski and his co-star Claudia Cardinale, both veterans of European New Wave cinema, were at that time better known to American audiences for their roles in, respectively, For a Few Dollars More and Once Upon a Time in the West. In general, however, the formula does also allow for moments when a film just breathes easily, to a rhythm of its own. In one of its boldest applications, Heart of Glass (1976), the actors playing the inhabitants of a late 18th-century Bavarian village dependent for its livelihood on the local glass factory performed throughout under hypnosis (the poor fools are sleepwalking towards catastrophe). The only un-hypnotised actor, Josef Bierbichler, plays Hias, a visionary herdsman often identified with Herzog himself, whose infallible prophecies in effect script the film. The marked differences in performance style between Bierbichler and the other members of the cast help to divide inner from outer narrative.

Of greater interest than either sequence of events, however, is what happens in the gap between them. Herzog has always insisted that a film is made in the camera, not the edit suite. In Heart of Glass, however, which was edited by Beate Mainka-Jellinghaus, a long-serving ‘helper’, the tried and tested techniques Herzog claims to despise (parallel editing, a key shot/reverse-shot sequence) combine to create a third narrative space, neither wholly inner nor wholly outer. The use of such techniques draws a subtle connection between hero (Hias) and villain (the mad, murderous factory-owner). Both men end up in jail, one because he set light to his own factory, the other because he foretold the conflagration. When Hias remarks that he would like nothing better than to get back to his cattle, the response is telling: ‘And you don’t want to see any people? I like you. You have a heart of glass.’ A heart of glass, whether it beats in prophecy or in mania, will remain forever indifferent to mere human concerns. This is Herzog’s most complete depiction of the ecstatic truth bro couple.

The closest equivalent to Straubinger in the fiction films is Kaspar Hauser, the teenager who turned up in a square in Nuremberg on 26 May 1828, in peasant dress, speechless apart from a few rote phrases. Kaspar’s behaviour soon made it clear that he possessed no conception at all of ordinary existence. By his own later account, he had spent the whole of his life up to that point confined to a sunless basement or shed, surviving on the bread and water brought to him by a keeper whose face he never saw. Kaspar is played by Bruno Schleinstein (always credited, at his own insistence, as Bruno S.), a 26-year-old Berlin truck driver and street musician who as a child had been so badly beaten by his mother that he lost the ability to speak, and thereafter spent miserable years in a variety of institutions. The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser holds its breath on more than one occasion as it ties in a knot the threads of an inner narrative moving ‘in all directions’ through a grand vision that owes a good deal more to Herzog than it does to the historical record. Fini got the fantasy of flight; Kaspar gets a dream based on some 8 mm film shot by his brother, Lucki, in a valley full of temples somewhere in Burma and, as a deathbed scene, the beginning of a story Herzog had long wanted to tell about a desert caravan. The outer narrative, meanwhile, caricatures those representatives of ‘human society’ – policeman, parson, town clerk, philosopher, philanthropist – whose sole ambition is to bully or cajole Kaspar into conformity. But the film’s achievement lies elsewhere. As long as its dramatic focus remains on the protagonist, it breathes easily. Under Herzog’s direction, Bruno S. summons into opaque vivacity a singular being as remote from the arbitrary orientalism of the fantasies wished upon him as he is from the banal groupthink of his entourage. ‘His appearance was always rough,’ Herzog says, ‘as though he slept under bridges even though he had an apartment, but his face and his imposing speech gave him an unconditional dignity.’ Bruno S.’s performance in The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser has something ecstatic truth just can’t buy: mystery without mystique.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.