The first impression of Lucie Rie’s work is of circles. Spirals, rings and discs characterised her ceramics from the beginning and although the exhibition at Kettle’s Yard (until 25 June) is arranged, with admirable clarity, in a chronological sequence, that too suggests a circularity, themes revisited and variations played out over time. One of the most beautiful pieces, a pink porcelain bowl with a golden manganese rim and turquoise bands, was made in 1990, when Rie was 88. Its ancestors, standing around it, date back to the 1950s when she began, or rather resumed, her career in England.

Born Lucie Gomperz into a wealthy Jewish family in Vienna, Rie left only just in time in October 1938. She and her husband, Hans, had ignored friends’ warnings because, as she later explained, the Nazis were thugs and she didn’t see why she should give in to them. They arrived in London and Hans later went on to the United States. Lucie stayed and made her reputation in England. This exhibition, unlike some, gives full weight to her prewar work, making the point that she was highly accomplished and already well-known in Austria, a prizewinner in the 1937 Paris International Exhibition. In one of the catalogue essays the potter Edmund de Waal sets her in the Viennese context. Her career began there at a moment of flux, somewhere towards the end of the Wiener Werkstätte and the beginning of Modernism. It was this crux, de Waal suggests, that made it possible for Rie to define herself by contradistinction and find her style. She also made a break from the comfortable family life of summer holidays on her grandparents’ estate at Eisenstadt and a fully staffed household. In 1928 she commissioned Ernst Plischke to design a studio and apartment for her. It was an essay in modernist clarity and transparency with glass vitrines for her work. She thought Plischke the best architect in Vienna and he was, to some extent, an influence. She admired his ‘simple lines’, adding that ‘he taught me what was necessary.’ After the war she arranged to have the whole interior brought to London, where the architect (and fellow refugee) Ernst Freud adapted it to fit her mews house in Paddington. It took huge effort, a lot of money and many bureaucratic manoeuvres to get it out of Vienna, but Rie was by nature persistent to the point of stubbornness, and this was, perhaps, another way of showing the Nazis that they hadn’t won.

Some of the few pots she brought with her from Austria are in the show. They are earthenware, darker and heavier than the later work, but they have great poise. In her ‘Credo’, an undated manuscript of about 1951 when, perhaps considering her contribution to the Festival of Britain, Rie set out her thoughts on pottery, she wrote: ‘There is nothing sensational about it only a silent grandeur and quietness.’ The early pieces already exude those qualities. They also demonstrate her most significant innovation, which was to decorate unfired clay. Initially this was a question of convenience, but it became her modus operandi. A final catalogue essay by Nigel Wood explains, for those who want to know the technicalities, something of the process of throwing pots, which he describes as a ‘dialogue with gravity’, and of glazing. The exhibition itself, understandably anxious to avoid the tendency of ceramics shows to treat their subject as hobby-craft, is mercifully light on the details of glazes and firing temperatures. What is important to understand is the extent to which Rie invented not only new forms but an original way of working that suited her both aesthetically and practically. It was a technique rapid enough to allow her to experiment. She also found ways to integrate coloured clays and to exploit supposed flaws, such as bubbled surfaces, for decorative purposes. All this she was able to do while operating in a small studio with minimal mess. Visitors familiar with other potteries often commented on the neatness of Rie’s studio and her pristine white apron. It was a telling contrast to the prevailing style of British craft ceramics at the time she came to England. Dominated by Bernard Leach, whose tendentious and quasi-philosophical A Potter’s Book appeared in 1940, it cultivated a masculine, not to say macho, image of the pottery as essentially rural and involving many sheds and much heavy lifting, the digging of clay and chopping of wood for the kiln. Rie was, as Leach’s third wife Janet put it, ‘a feminine no-shovel potter’. She used an electric kiln, which was anathema to the brown-pot brigade. At first she was disconcerted by the Leach ethos, but after a few experiments in that direction she regained her balance. Later, she won Leach round. Always a man’s woman, she made him into a close friend and an occasional lover.

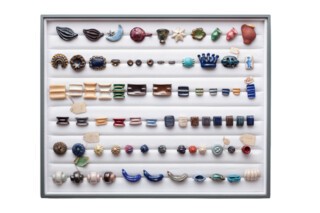

Rie consistently claimed that her pots weren’t ornaments, that they were made for use, although over time this was less likely to be the case, not least because the bowls and bottle forms that made up the bulk of her work were too expensive to risk for more than a single stem or some pot-pourri. At first, however, the need to earn a living combined with wartime restrictions on manufacturing pushed her into purely functional work. With a team of assistants, many of them fellow refugees, she made buttons. Beyond its utility, Rie never had a good word to say for this phase, which was unique in her career in being both collaborative and partly mechanised, but the two displays of buttons at the beginning of the exhibition, shown in rows like juicy sweets, are suggestive as well as attractive. Miniature essays in form, colour and surface, they evince an experimental freedom with glazes and a formal spontaneity. They were popular at the time. Clothing was still rationed and utility wear could be livened up with distinctive buttons. In 1984 they marked another cycle in Rie’s work and life when she met Issey Miyake. They exhibited together in Tokyo and in 1989 he used her buttons in his Autumn/Winter collection.

After the war the restrictions lifted and Rie’s career resumed. She became a British citizen, and the Church Commissioners, the freeholders of her house in Albion Mews, granted permission for a pottery on site as long as she produced ‘high class’ wares. The tea and coffee services of those years have a smooth Moderne feel. Even better are the salad bowls. Rie knew just how far to pull out a lip from a perfect circle to make the bowl more useful and give it at the same time a little twist, a dash of wit, a syncopation. The work of the later 1940s and the 1950s is full of the neo-Romantic joie de vivre that ran through postwar art and design. A zesty lemon yellow and light striations now appeared, to become part of Rie’s permanent repertoire. Like Moore and Hepworth, she was interested in prehistoric art. A visit to the stone circle at Avebury and the museum display there of Bronze Age vessels was inspiring and was combined in Rie’s vision with the Roman pots she had seen in her uncle’s collection in Vienna. She adapted the sgraffito technique, achieved with bird bones in the Bronze Age, using a steel needle instead. There was also something of the abstract reliefs of Ben Nicholson in the subtle play of white glazes in her work from this time. Not every experiment came off. An inlaid stoneware vessel decorated with a form like a seed head comes too close to the figurative, and the rising and falling wave pattern on a vase of the same period is also uncharacteristically clumsy. Clearly related to the fashionable textile designs of Lucienne Day and others, the motifs don’t translate into three dimensions. Rie’s best work comes when the entire form harmonises, when interior and exterior form a continuum, like a Möbius strip to the eye.

In the 1960s she introduced the long-necked bottle forms, rising to a flaring mouth, which became, like the bowls, a central theme in her work. They were thrown in two pieces, a process that she demonstrated to David Attenborough when he interviewed her in 1982 for a short BBC film. The film, which coincided with a retrospective of her work at the V&A, is on show at the exhibition and gives a flavour of Rie’s laconic, sour-sweet temperament. Her answers to his questions are brief and when he misunderstands he meets with a curt ‘no’. It culminates in the opening of the kiln: Rie, who was less than five feet tall, pivots on the edge to reach the pots and asks Attenborough, slightly flirtatiously, to ‘please hold my leg’ so she can get out. The bottles range from pure white static forms as poised as Cycladic figures to some of the most exuberant objects she ever made. The examples with integrated spirals of different coloured clay veer towards the bubblegum end of the spectrum, while other pieces are positively blingy. She sometimes got carried away with golden manganese glaze. At their best, however, the bowls and bottles enhance each other. In one of the displays at Kettle’s Yard, a blue and black Vase with Flared Lip in porcelain from about 1978, rising in rhythmic waves of expansion and contraction, stands with a Straight Sided Bowl of 1970 (also porcelain), banded in red, black and gold. Not intended as companion pieces, they nevertheless create a Morandi-like dialogue of forms, the small foot of the bowl speaking to the narrow neck of the vase and the space between them making its own interesting shape. As this sociability in her work and the Attenborough film make clear, Rie was not reclusive, as was sometimes suggested. I interviewed her in 1988 for the Guardian and found her steely but forthcoming. She regularly entertained friends in the Viennese manner to coffee and cake. She was, however, uninterested in publicity for its own sake. As she remarked, she wanted a private life, and ‘such privacy attracts public interest’. What she mostly wanted was to get on with her work. She gave up teaching after a brief spell at Camberwell College of Arts and Crafts that was not, as Tanya Harrod puts it, ‘a positive experience’. Harrod’s essay sets Rie in her historical context, not only the modernism from which she emerged and the Leach school which she avoided, but the ‘rich and complex’ developments in studio ceramics from the 1960s onwards, which she ignored. The slab-built works of potters such as Alison Britton, Gordon Baldwin and Gillian Lowndes moved away from wheel-thrown pots partly in order to escape the pejorative associations of ‘craft’ in favour of the cultural high ground of Art. Could pottery be art? It was a debate that raged, albeit in limited circles, around the Crafts Council in the 1980s, too often ending up with heated arguments about function. Should a teapot pour? Rie had no truck with this. When asked about theoretical or critical questions she would answer with crisp finality: ‘I make pots. It is my profession.’

She once said that art that was ‘alive’ would always be in some sense modern, and she has been vindicated. Nearly thirty years after her death, her bowls and bottles haven’t dated. Neither, arguably, have the studio potters or Leach, but they are recognisably of their time. Rie remains curiously outside time or, indeed, place. There are lingering memories of Continental modernism, some touches of the Viennese in her work, but it doesn’t look like either, nor does it seem in any obvious way English. This exhibition brings out qualities that more limited surveys, or the many occasions on which she has been shown alongside her friend and fellow refugee Hans Coper, have obscured. It is a pity that the accompanying book hasn’t been better edited. The essays, although for the most part strong individually, repeat much of the basic information and occasionally contradict one another. Overall, however, the show is a joy. There is a powerful inevitability about Rie’s best work. I found myself thinking of the gnomic phrase the antiquary William Stukeley used to describe Stonehenge: ‘It pleases like a magic spell,’ mysterious but charming.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.