Halfway around the Donatello exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum (until 11 June) we encounter two bronze roundels of much the same size, both representing the Virgin and Child with angels: the Chellini roundel from the museum’s own collection and one lent by the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. In the first, the drapery has countless small, wriggling folds resembling a heap of tangled string. In the second, the folds flow gracefully and clarify form; an angel’s tunic is gently lifted by a breeze and the end of the veil wrapped intricately around the Virgin’s head is pulled taut by her playful child. In the Chellini roundel, the six figures appear to be welded together, whereas in the roundel from Vienna the contours of the figures are distinct, the areas between each clearly defined, as is the space they occupy; the veil behind the Virgin’s face is in front of the festoon that the angels are trying to suspend. In the V&A’s roundel there is no obvious tooling of the bronze after casting; in the other, every surface is precisely chased and burnished.

Elsewhere in the exhibition we are introduced to the pictorial, low-relief carving of marble that Donatello seems to have invented and which is now universally referred to as rilievo schiacciato (squashed or mangled relief). By this means, aerial perspective was introduced into sculpture for the first time – and almost in advance of its reintroduction into painting. But we also find reliefs in both bronze and marble which are composed of figures crushed into the front plane. These might more appropriately be called schiacciato, and are set against a mosaic ground that denies any sense of depth. In one early relief, known only in stucco casts, the architecture supplies a geometrically articulated space which in the accompanying label is appropriately likened to Masaccio’s altarpiece in the National Gallery; but in Donatello’s later reliefs superimposed architectural elements create a background of deliberate spatial confusion. A partial explanation for this development may be competitive divergence: Donatello was driven to devise original solutions by the success of the older Lorenzo Ghiberti, whose mastery of linear perspective in relief sculpture could never be surpassed. But there can be little doubt that Donatello also came increasingly to relish angular collisions of form, rough finishes, ragged edges and natural disorder to a degree never previously found in sculpture. Such are the qualities most apparent in the V&A’s Lamentation, a bronze relief of unknown origin which is completely antipathetic to the ideals of the goldsmith.

If there was one type of sculpture in which Donatello sometimes failed to excel it was the free-standing, full-length marble figure. The great gloomy prophet Habbakuk made for the Duomo in Florence and the noble St George made for Orsanmichele are masterpieces but they were intended for niches and may thus be regarded as a sort of high relief. The earlier free-standing marble David with which the exhibition opens is awkward in articulation and not only (though most obviously) in his impossibly flexed wrist, being also unresolved in expression, and with attempted movement impeded by the narrow block. Towards the end of the exhibition we meet the equally awkward unfinished marble David from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, ingeniously placed before an opening so we can compare it with the earlier work. Its condition is best explained as a reflection of the ageing artist’s impatience with the character of carving, which allows no revisions. Neither marble has anything of the natural poise, let alone the pagan aplomb, of the far more famous nude David, cast in bronze and represented here by a plaster cast with a bronzed finish.

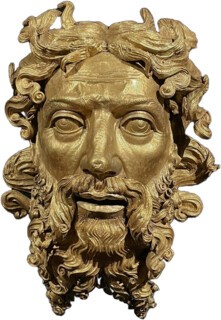

The exhibition places an emphasis on Donatello’s hypothetical training as a goldsmith, which ‘clearly fuelled his creativity’ and prepared him to work in different media. A video screen – a pity it’s so prominent – shows clay being modelled and marble chiselled. These techniques are relatively familiar to most visitors. The making of clay and stucco sculpture from moulds, the beating-out of silver or copper sheets to create repoussé sculpture, the process of mercury gilding, the casting of bronze, and the filing, patching, punching and chasing that follow casting might have been illustrated instead. The video, in fact, is flanked by a moulded terracotta relief on one side (surely it was moulded, not modelled, although both label and catalogue seem uncertain) and a large gilded repoussé copper head on the other.

The latter item, a head of God the Father from Milan Cathedral, is perhaps the most surprising item in the whole exhibition, as well as the most conspicuous. The impact of this little known work depends less on the dimpled mask which serves as the face than on the bold projections of more than thirty separately wrought locks of hair or beard riveted or soldered onto it. Although there is no direct connection with Donatello, it shows a type of metalwork which he must have known and which, it is suggested, he himself probably employed, although there is no documentary evidence for this.

We encounter examples of repoussé work more commonly in the form of reliquaries fashioned as a sort of bust. Donatello’s San Rossore reliquary, included in the exhibition, departs from this tradition not only in its particularised, portrait-like character but in being cast in bronze rather than hammered in silver or copper. Near this is the Chellini roundel, a relief cast in bronze of a uniform thinness, with the hollow interior conforming to the exterior relief, as would be the case with repoussé work – in fact it was compared in the early 19th century to a superb Hellenistic mirror-back executed in this technique (as I revealed long ago, in the LRB of 4 June 1981).

What determined this miracle of bronze casting, however, was surely not Donatello’s emulation of repoussé but his fascination with the technology of casting, for the hollow interior was devised to serve as a mould from which glass paste reliefs could be made. The use of glass for this purpose was also an innovation. More usual materials were softened leather, cartapesta (papier mâché), stucco or clay, all of which were sufficiently flexible to be peeled off or pulled out of the mould, provided that the mould was made from a shallow relief with limited undercutting.

The exhibition is more concerned with exploring themes than with tracing Donatello’s development. Thus reliquary busts are lined up with portrait busts, and low-relief works by Donatello and his great follower Desiderio da Settignano are grouped together. A section devoted to Donatello’s hyperactive, mischievous and occasionally slightly menacing infants is perhaps the most successful. But the related section intended to illustrate the impact of antiquity is less compelling – unsurprisingly, since the sources for his fascination remain something of a puzzle. Certainly engraved gems and Roman sarcophagi meant more to him than the restored marble statues that we think of first in this connection.

Among the sculptures that have not previously been seen in London is a bronze corbel made for the pulpit in Prato, near Florence, from which the Virgin Mary’s girdle was exhibited on the feast day of the Assumption. It is hard to light and to photograph but we can still detect the unprecedented vitality given to every ornament – leaves rhymed with wings, scrolls turning into leather straps. It is inspired by rare types of ancient Corinthian capital, which Donatello must have studied during his visit to Rome, and incorporates infants of three sizes and two nude but helmeted youths which seem like preliminary models for the bronze David.

At every stage the exhibition illustrates Donatello’s influence, including what must have been something of a rediscovery fifty years after his death by Bandinelli and others in Florence, and concluding with a section on his reputation and his imitators in the second half of the 19th century. The fifth centenary of his birth was celebrated in Florence in 1887 with a huge exhibition in the Bargello which helped to give that recently founded museum the shape it retains to this day. It established Donatello as worthy to stand beside Michelangelo, Bernini and Canova and also confirmed his position as the dominant figure in 15th-century Florentine art. What surprises the scholar looking back on this great event today is not only the original works it included but the plaster casts – more than sixty of them – and the rooms of photographs which were also featured.

In the second half of the 19th century, three developments revolutionised awareness of the art of the past: improvements in the conditions of international travel; the growth of photography; and the creation of extensive collections of plaster casts. Most of these cast collections have been destroyed or dispersed. Few visitors to the Metropolitan Museum in New York or the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest (to give just two examples) realise that the cast collections they housed were once their chief attractions, but the marvellous Cast Courts of the V&A have survived. Many of the visitors to the Donatello exhibition will already own well-illustrated books of his work; many will also have travelled to Florence, Siena and Padua to see works by Donatello that can’t be moved; and a good number of them probably also travelled to Florence last year to see the exhibition in Palazzo Strozzi and the Bargello; but very few will have taken the opportunity to study what is available in the Weston Cast Court at the other end of the museum. They should have been directed to do so.

You will find there a cast of the St George for Orsanmichele – a far more successful sculpture than the early David at the start of the exhibition, even if it is much in need of its niche. Near it, there is a cast of a very late life-size figure, the rough bronze of the terrifying John the Baptist made for Siena Cathedral. On one wall you encounter the Cavalcanti Annunciation in Santa Croce and, high on another wall, a cast of the choristers’ gallery (the Cantoria), made at a similar date for the Duomo. The originals of these works will never leave Florence, but neither will they ever be seen there together. Both of them illustrate Donatello’s architectural achievements, hardly touched on in the exhibition except by the great corbel from Prato. The pillars framing the Annunciation, with their fish-scale ornament, scrolled bases and mask capitals, are inventions which, like those of Michelangelo, Borromini and Piranesi in the following centuries, are hard not to understand as a sort of anti-classicism, though they are derived from the study of fragments of Roman antiquity.

Donatello’s relief of wildly dancing infants in his gallery for the Duomo was designed as a contrast to the perfectly behaved older children in the one by Luca della Robbia. Casts of both galleries are to be seen here and reinforce our sense of the intensely competitive character of Florentine art. There is also a cast of the great baptismal font in Siena on which the little dancing putti in the exhibition were originally perched. And incorporated in its base, albeit slightly damaged, is a cast of the most powerful of all narrative reliefs by Donatello: Herod horrified by the sight of the head of John the Baptist. Nearby, there are reliefs by Donatello’s predecessors and competitors. More of Donatello’s work for the high altar of the Santo in Padua is represented and there are other casts that I have not mentioned.

So there are really two exhibitions devoted to Donatello at the Victoria and Albert Museum today, both the result of intensive international diplomacy and generous collaboration (the casts came not only from Florence but from Berlin). One exhibition provides a short-lived opportunity to examine genuine pieces by his hand, to marvel at their variety, to debate the status of some of his work and to assess the nature of his influence. The other is a permanent display which shows more of his monumental achievements and, by the comparisons it enables, increases our understanding of them in ways not possible even when we stand before the originals.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.