Archer Huntington , whose collection is now on display in Spain and the Hispanic World: Treasures from the Hispanic Society Museum and Library at the Royal Academy (until 10 April), was something of an oddity. Unlike the other masterpiece hunters of the late 19th century, Huntington was more of a taxonomer, acquiring hundreds of thousands of objects to create ‘a broad outline without duplication’ of Spanish and Hispanic art and culture. He wanted, as he put it, to ‘capture the soul of Spain in a museum’ and, in May 1904, he founded the society as a free public library, museum and educational institution. The RA show is the last leg of an international tour while the Society’s neoclassical buildings in Washington Heights are being refurbished.

The selection in the main galleries reflects Huntington’s original taxonomic intentions, with a daunting array of objects from 2500 BCE to the early 20th century, ranging from silk textiles and ceramics to maps, metalwork, jewellery and furniture – as well as paintings, drawings, prints and sculpture. The variety is bewildering: archaeological fragments rub shoulders with masterpieces such as Velázquez’s Portrait of a Little Girl, a magnificent pyxis from Umayyad Córdoba and a silver tray decorated with chinchillas, lions, birds and flowers from 18th-century Bolivia. The final room recreates at a reduced scale Joaquín Sorolla’s huge panorama known as the Vision of Spain (1911-19), commissioned for the New York galleries by Huntington to represent a Spain that was already ‘on the point of disappearing’.

Huntington was the adopted son and heir of the railway and ship-building magnate Collis Huntington. His mother, Arabella, was the daughter of a carpenter-machinist in Virginia, who, after a brief marriage to a local businessman, was set up in Manhattan by Collis. It is widely assumed that Collis was Archer’s father: he adopted the boy in 1884, after the death of his first wife and his marriage to Arabella. Arabella had by this time acquired a taste for fine European paintings and decorative arts, and in 1882 they crossed the Atlantic to prepare 12-year-old Archer for the life of a collector.

He would by then have encountered Orientalism in the ‘Moorish Room’ curated by Arabella in their New York house, but his introduction to Spain was a book about gypsies bought soon after disembarking. Perhaps unsurprisingly, his diary describes this as ‘much more interesting than Liverpool’. And although he didn’t visit Spain until 1892, he began to acquire antiquarian Spanish books, turning down his father’s offer of a job at the firm in order to catalogue his budding collection. His first experience of Hispanic culture was a formal dinner in Chapultepec Castle hosted by the Mexican president, Porfirio Díaz, in 1889.

North America was suffering from ‘Spanish fever’. The obsession with the Hispanic had begun to incubate in the 1870s, slowly overcoming the deeply entrenched myth of the Black Legend, which characterised Spain as a country of cruel and unenlightened Catholic zealots. Thomas Eakins visited Spain in 1869, followed later by John Singer Sargent, Mary Cassatt and others, bringing back visual and written descriptions of a country they thought both colourful and charming. The ‘Spanish craze’ reached epidemic proportions in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War of 1898, influencing not only tastes in art and architecture but also in music, theatre, cinema, literature, fashion and food. By 1911, Henry Clay Frick had acquired Velázquez’s portrait of King Philip IV of Spain for $475,000, the highest price he had ever paid for a painting. William Randolph Hearst shipped over cartloads of hispano-moresque plates, furniture, choir screens, even entire cloisters for his new castle in California. As one Spanish reporter put it, ‘we discovered America, and now Americans have discovered us.’

Huntington’s first paintings, including Anthonis Mor’s fearsome Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, Third Duke of Alba (1549), were given to him by his father in 1898. He was hesitant at first to buy his own, trusting neither his knowledge nor the scruples of dealers and other intermediaries (he described Joseph Duveen as a ‘serpent charming a bird’). Velázquez’s Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares, on Horseback was bought for him by his mother. Huntington imposed on himself a rule to buy only outside Spain – ‘to Spain I do not go as a plunderer,’ he declared – although as an amateur archaeologist he unearthed several Roman items and bought Bell and Beaker bowls from George Bonsor’s dig at Carmona. More controversial was his purchase of the library of Spanish literature amassed by the Marquesado de Jerez de los Caballeros, head of the Andalusian Bibliophile Society. The impact of this transaction was described by the historian Ramón Menéndez Pidal as ‘greater for Spain than the loss of Cuba’. But to be fair to Huntington, most of his acquisitions came from dealers in Paris, London and New York, even if they had him in mind when removing the objects from Spain.

Huntington called these objects ‘specimens’ and, for all its treasures, his collection was a product of late Victorian ethnography that painted the Spanish as an essentially ‘oriental’ race. Although he patronised artists such as Sorolla, Ignacio Zuloaga and Santiago Rusiñol, the works he chose are folkloric. He lived until 1955, but stopped collecting in 1930 and bought no works by Picasso, Gris, Dalí or Miró. A few objects from the New World, including a 16th-century watercolour of the Mines of Potosí and a blue and white jar produced in mid-17th-century Mexico, were acquired by Huntington himself, but most of those in the collection have been added in recent years. These will be critical to the museum’s success with the largely Hispanic local community when the neoclassical building reopens next year. The brief reopening last summer, titled ‘Nuestra Casa’ and curated by Madeleine Haddon, acknowledged the need to highlight the often appalling context depicted in, for example, the painting of Potosí, where millions of slaves died to enrich the Spanish Empire. It also showed works such as Velázquez’s Portrait of a Little Girl ‘in dialogue’ with colonial works such as El Costeño (c.1843), by the Mexican artist José Agustín Arrieta, which depicts a young man from the Gulf Coast, the entry point for millions of African slaves. We don’t know the subject’s name, but it is clearly a portrait, and the sense of place is captured magnificently by his basket of bright tropical fruit.

Even if the display is at times difficult to process, this is a rare opportunity for British visitors to see the diversity of Spanish and Hispanic arts, and to stand in front of works such as Goya’s Duchess of Alba (1797). The collector Louisine Havemeyer passed when it was offered for sale in 1906, failing to appreciate (as the art historian José Luis Colomer notes in his book about American collectors) the treatment of black as a stepping stone between the Spanish tradition and painters such as Manet. It hangs alongside three drawings by Goya and his Portrait of Pedro Mocarte (1805-6), whose toreador-like costume and forlorn expression encapsulate both the romance and isolation of 19th-century Spain. El Greco’s Pietà is one of his few surviving works from Italy, and his Miniature of a Man reminds us of his proficiency as a painter of piccola pittura.

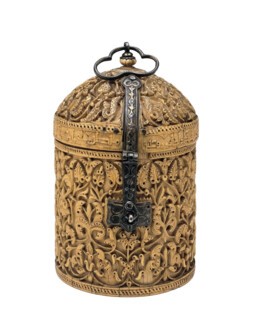

In the first rooms, dedicated to the ancient world and Al-Andalus, Celt-Iberian silver bracelets sit alongside Roman trullae and a Visigothic copper alloy, garnet, glass and cuttlefish bone belt buckle. The Córdoban Pyxis (c.966) is one of about 35 ivories carved in workshops at the palace city of Madinat Al-Zhara for the caliph’s close family and associates. An inscription tells us the name of the carver, Khalaf, and offers us an ekphrastic poem comparing the object’s beauty to the breast of a young woman. Also from Islamic Spain are two silk textiles, one of them with a central band featuring scenes of women drinking and addorsed gazelles. Although figurative imagery wasn’t condoned in devotional contexts, these silks were often given as gifts or purchased by well-to-do Christians. Lustreware vessels, around a dozen of which are on display, were also prized by Christian patrons, not only in Spain but in Italy too. The tin-glazed earthenware baptismal font from Toledo (c.1400) represents the Mudéjar style that emerged after the so-called Reconquista, as Christians and Jews emulated the sophisticated culture of the courts of Al-Andalus. Its decorative scheme alternates the cross of Golgotha and IHS monogram with the khamsa or ‘Hand of Fatima’.

Spain’s unique cross-confessional environment is also evident in the work on display from the medieval and early modern periods. Take, for instance, the Hebrew Bible dating from the mid-15th century. Here the gold text is surrounded by colourful borders of rinceaux, acanthus leaves, peacocks, dragons and the crest of the (unknown) patron. This Bible is one of several Hebrew texts illuminated by artists who were probably Christian, the most famous being the Golden Haggadah in the British Library. Also in this section is Juan Vespucci’s World Map of 1526, an ornate copy of the master nautical chart distributed in Seville to navigators, which may have been a gift to Charles V on his marriage to Isabella of Portugal. Not far from these objects is a pair of polychromed wood busts of an Ecce Homo and Mater Dolorosa by Andrea de Mena, one of few named female sculptors from the 17th century. Andrea was the daughter of the sculptor Pedro de Mena and entered a convent aged twenty, perhaps to focus on her craft without the hindrance of childbearing. The display of such different objects – Hebrew Bible, navigator’s map and polychromed Christian sculptures – in a room that also houses 17th-century ‘Golden Age’ paintings and late-16th-century metalwork, is the weakest aspect of the exhibition. Given its chronological organisation, tighter groupings would have provided a better sense of the different contexts in which these objects were commissioned, produced and received.

Works from the New World include luxury goods made using local materials and motifs, and often produced in response to ceramics, textiles and lacquerware imported from Asia. The finish of a beautiful barniz de Pasto portable writing desk (c.1684) is resin from the Colombian Mopa-Mopa tree applied onto painted peonies, carnations, parrots and monkeys. Nicolás de Correa’s Wedding at Cana (1696) is an example of the enconchado technique inspired by Japanese Namban. The background, faces and food and drink on the tables are painted in oil, but the shimmering garments are inlaid mother of pearl. Several sculptures in the European technique of polychromed wood depict subjects unique to the Spanish colonies. The Four Fates of Man: Death; Soul in Hell; Soul in Purgatory; Soul in Heaven (c.1775), attributed to the Ecuadorian Manuel Chili, was probably intended for a devotional setting, but – as the only work of its kind – is difficult to contextualise. The vividly coloured half-length figures represent the possible trajectory of the soul, with the agonised scream of the damned and glass tears of the figure in Purgatory warning us that neither would be a great place to end up.

The painters here are both Spanish, such as Sebastián López de Arteaga, and born in the New World, such as Juan Rodríguez Juárez. Arteaga’s Saint Michael, painted in oil on a large copper plate, is one of many depictions of the saint throughout the Spanish Empire, largely following (widely available) Netherlandish prints. The promotion of Michael’s cult by the Jesuits and Franciscans as a transitional figure between local religions and Catholicism no doubt played an important role. Rodríguez Juárez’s Mestizo and Indian Produce Coyote (c.1715) is one of many ‘Casta’ paintings produced in Mexico to feed the Spanish rulers’ obsession with racial classification.

In the final, modernist rooms Zuloaga’s Family of the Gypsy Bullfighter (1903) and gory The Penitents (1908) evoke the Spain of the past. The Sorollas, delightful as they are, remind us of the flamenco fiesta promoted by Franco to boost postwar tourism. It’s not the Hispanic world as we know it today, but a glimpse of the shaping of its cultures across 2500 years and three continents.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.