In 1932, aged seventy, Hilma af Klint rewrote her will. She stipulated that her paintings, notebooks, drawings and writings be kept from public view for at least twenty years after her death: by then, she hoped, audiences might be ready for her work. In the event, it took more than four decades for it to be seen in public. In 1986, a selection of paintings were included in The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art alongside work by better-known contemporaries including Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian. The revelation of the exhibition was that af Klint’s abstraction predated that of her peers by several years. Here was the ‘first’ abstract painter, usurping Malevich and his 1915 Black Square. Not everyone agreed with this interpretation. The critic Hilton Kramer argued that the curators had only accorded af Klint such ‘inflated treatment’ because – ‘dare one say it’ – she was a woman. It wasn’t until 2013 that there was a major retrospective of her work, at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm.* Every one of her works has now been reproduced in a lavish seven-volume catalogue raisonné. Since the lion’s share of her work remains with the Hilma af Klint Foundation, the usual information about provenance seems unnecessary, and it’s hard to know who might need a compendium like this one. There aren’t substantial critical essays in the volumes, but the reproductions are beautiful.

Af Klint grew up in a liberal Lutheran family of naval cartographers and it’s tempting to see traces of this inheritance in the lines and spirals of her intricate paintings (the aristocratic ‘af’ was awarded in 1790 for the family’s contribution to the Russo-Swedish War). She went to study at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm in 1882 and after graduating exhibited several times a year in group shows in Stockholm. She was from a wealthy family and didn’t really need to make money from her art, though she did illustrate some children’s books and sell some landscapes. In 1900, she and her friend Anna Cassel spent a year at Stockholm’s Veterinary Institute. They had been hired to produce illustrations for a teaching manual, which the school’s director hoped would raise the status of the profession in line with medical doctors. They were paid by the page for their drawings of corpses and dissected animals, receiving, despite the stench, an unprecedented education in anatomy: few of their fellow artists could claim to have seen so many ‘ovaries, sperm, uteri and sperm ducts’, as Julia Voss writes in her new biography. Abstracted versions of these organs, as well as other body parts, appear in af Klint’s paintings. The institute wasn’t far from Blanch’s Café, an important meeting place for Stockholm’s avant-garde and, later, for the European artists who took refuge in the city during the First World War, among them Kandinsky.

As a teenager, af Klint joined the circle of Bertha Valerius, an artist and medium, and began to attend séances regularly (she joined the Theosophical Society in 1904, ahead of Kandinsky and Mondrian). Her first direct contact with the spirit world had come on midsummer’s day 1886, when a spirit announced: ‘I want to speak to Hilma.’ Another message, spelled out on a psychograph tablet, instructed her (rather vaguely) to ‘Go calmly on your way.’ In 1896, during a séance at the Edelweiss Society, af Klint and Cassel founded De Fem (‘The Five’) with three other women. De Fem wore matching brooches and met weekly. Each session opened with a prayer in front of an altar, then the women held hands to form ‘an electrical circuit’. The communications they received were documented in a series of nine notebooks. Over time, De Fem became seven, and then thirteen, before the sisterhood disbanded in 1908. Af Klint and Cassel drifted apart, having fallen out over money – what Cassel considered a loan had been understood by af Klint as a gift – and only began speaking again after Cassel died.

In 1906 af Klint received a ‘commission’ from a spirit to produce a series of ‘astral paintings’, marking the beginning of her relationship with a group of benign and encouraging spirits, whose advice, suggestions, instructions and exhortations she followed and carefully recorded in her notebooks. This rag-tag bunch of ghosts included Ananda, Georg, Amaliel and Gregor, a priest from the Middle Ages who was seeking to free the church from Catholic heresies. One early message that af Klint transcribed warned that ‘Hilma will receive a great gift, if she never forgets the power of the highest,’ a pact she entered into willingly. It was a spirit who insisted that ‘the paintings must remain hidden from the eyes of the general public until the time to come forward is possible.’ Another suggested, and af Klint acquiesced, that she should become a vegetarian.

She started to make drawings during séances on the instruction of a spirit called Esther, who commanded: ‘Take the pencil, Hilma.’ It was good advice: filling a pen with ink would have slowed her pace. She sometimes drew using a planchette, a wooden tablet and pencil contraption (De Fem had a luxury version made of brass and mounted on wheels). The British spiritualist artist Georgiana Houghton produced hundreds of abstract, watercolour drawings in the 1860s under the guidance of various spirits, and there are similarities between her electric, spiralling lines, which loop the page in Technicolor whorls, and the ones af Klint created during séances. It was said that Houghton could make the dead appear at séances, or sometimes a banana (and ‘then a watermelon and a coconut’).

The 26,000 pages of notebooks and sketchbooks af Klint completed over the course of her life are filled with messages of humility and love. Voss has ploughed through her 1917 manuscript, ‘Studies of the Life of the Soul’ (2000 pages), in which af Klint ‘dictates her thoughts about the spiritual life’ – an eclectic muddle of religion, esoterica, natural history and spiritualism. Voss glosses the contents, passing on the most instructive of af Klint’s wide-ranging views on religion, nature and evolutionary theory. Despite her many notebooks, she left behind no personal diaries, and we know little about her thoughts beyond her art and spiritualist interests. Voss does a good job of filling in the gaps with detective work and speculation, although in places the conditional does a lot of heavy lifting. Her biggest achievement is to establish a context for af Klint’s work, upending popular assumptions that she was a mystical outsider who floated free of her historical and social milieu.

Her canvases are large and vibrant, washed in pastel-bright colours and overlaid with mandalas, hourglass-shaped infinity loops, grids, circles and spirals. Abstract and not so abstract references to the natural world recur – petals, vines and seedpods, or shapes that resemble them. In both the paintings and sketchbook drawings, geometry tussles with eccentricity. Her compositions alternate between austere abstraction and biomorphic allusion. Like her modernist peers, af Klint hoped to transcend the limitations of the physical world, but her sense of the ‘spiritual’ in art was the opposite of that described by Kandinsky in Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1911), in which he argued that the spiritual was an innate form of self-expression.

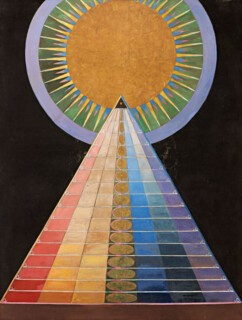

The ‘astral paintings’ the spirit Amaliel commissioned from af Klint in 1906 became the first in her long-running Paintings for the Temple cycle, which she planned to exhibit in a museum temple built specially to house them. Primordial Chaos was followed by Eros, Evolution, Large Figure Paintings and The Ten Largest, each of which, Amaliel decreed, should be ‘as big as barn doors’. The ten paintings are a riot of ovoid, floral and spiralling forms that chart the life course from birth to old age via abstract and symbolic motifs. The final series, Altarpieces, painted in 1915, took a different turn. In these images, striped prisms emit golden suns and coloured light waves. They look more masonic than modernist. They also signalled a shift in palette, becoming darker and more sombre in tone. Several of the prism forms luminesce against flat black backgrounds.

Fragments of the messages af Klint received made their way onto the painted surface, letters and words overlapping with abstract imagery. Colour carried significant symbolic weight. One notebook entry assigns colours to each of the spirit guides: blue and violet for Amaliel, gold and white for Ananda, green for Gregor (green also stood for ‘joy in life’). Blue and yellow meant male and female respectively, although she generally avoided binary thinking. Her notebooks and sketches depict ‘dual souls’, whose gender is neither singular nor fixed. Her own relationships were almost exclusively with women; she lived with Thomasine Anderson from 1918 until Anderson’s death in 1940.

Before her move into abstraction, af Klint, like Mondrian and Malevich, was a figurative painter. She made Post-Impressionist paintings of the Swedish landscape as well as line drawings of its flora and fauna. These were the works she showed in group exhibitions in Sweden between 1905 and 1914. In her notebook on ‘Flowers, Mosses and Lichens’, af Klint’s cursive handwriting is set alongside small colour sketches of spirals and circles. These are spliced and labelled specimens in a modernist schema. A spiral is only a spiral until it is a snail shell or a winding tendril. The notebooks and smaller drawings are more dispassionate than the paintings, although for many of her more recent fans af Klint’s appeal seems to lie at the headier end of things – the spirit guides, the secret societies and so on. Af Klint herself compared Primordial Chaos to ‘charts and logarithms for a seaman’, its ‘formula-like symbols’ and echo of scientific tables suggesting an alternative narrative, one rooted not in the celestial realm but in her family’s past and in human classification.

In 1908, af Klint invited Rudolf Steiner to Stockholm to see her paintings. She didn’t record the meeting in detail, but their subsequent correspondence suggests things did not go as well as she had hoped. Steiner declined her request for tutelage, writing that she seemed to be well served by her spirit guides and had no need for his earthly guidance. She stopped painting for four years after their meeting, but remained loyal, even visiting the headquarters of the Anthroposophical Society in Switzerland in 1920, bringing with her ten large albums containing miniature reproductions of her paintings, in the hope of continuing their conversation. Others also sought Steiner’s attention, including Mondrian, who sent him a draft manifesto, and Walter Gropius, whose invitation to teach at the Bauhaus Steiner ignored.

In the years before and after the First World War, various members of af Klint’s circle expressed fascist sympathies. Helena Blavatsky, the co-founder of the Theosophical Movement, proposed in 1888 that humanity would develop through seven ‘Root Races’ – from the first ‘ethereal’ race through the ‘Aryan’ race to a perfect ‘Pacific’ race, without sin or sexual difference – a notion readily transformed into racist propaganda. In 1923, Steiner gave a lecture on a future ‘white race’ and described the indigenous cultures of America as ‘degenerated’. We don’t know much about af Klint’s views, but she read widely across theosophy, anthroposophy and Rosicrucianism. When, in 1933, she described the coming ideology of ‘dark powers’ in her notebooks, she recorded spirit messages diagnosing Hitler, Goebbels and Göring as suffering from ‘megalomania’. Notes like these reveal a growing sense of disquiet. But whose exactly?

The question of agency here is vexed and political (it’s also gendered). Does the authorship of af Klint’s spiritualist paintings lie with the medium or her spirit guides? And why do so many drawings by mediums look so similar? Is this the visual language of the living or the dead? How do we distinguish between the ‘visionary’ artist and more explicit claims for spirit-world intervention? Voss acknowledges the difficulty of writing about a subject who ‘heard voices, saw images with her inner eye and was in contact with the souls of plants’, who ‘remembered previous incarnations and possessed healing powers’. She doesn’t promote a ‘sociological’ explanation for something that, as she points out, even af Klint struggled to make sense of. Instead, she describes af Klint’s experience of reality, refusing to ‘downgrade to the status of an expedient precisely the thing she regarded as key’. But this doesn’t help the reader who wants to know whether they should accept af Klint’s drawings and paintings as reports from the astral plane or think of abstraction as a form of world-building for af Klint and her contemporaries, framing spiritualism as context not content. Admitting both ideas has frequently proved difficult, even if it is what we must do.

Between 1913 and 1915, af Klint completed a series of pencil and watercolour drawings called Tree of Knowledge. These works suggest that she was working in dialogue with her spirit guides, rather than at their mercy. Delicately drawn tree roots morph into trailing colourful tendrils and jellyfish-shaped orbs. The spliced spheres and wispy tentacles of these micrographic worlds within worlds evoke a subterranean plane every bit as rich as the celestial one towards which the upper branches reach. This is not the frenzied automatism of drawings produced during séances, but a symbolic celebration of the earthly and divine. Voss claims that af Klint ‘captured world knowledge on a sheet of paper and compressed it into a diamond’. Like other ‘unusual artists of the century’, she writes, af Klint understood that the task of ‘detecting the invisible powers of the universe’ was not the preserve of scientists. Artists had a role to play in apprehending the ‘rays, waves and vibrations’ that were also central to modern science.

Swapping one kind of abstraction and field of speculation for another, the Hilma af Klint Foundation recently entered into an agreement with the publisher of her catalogue raisonné to produce printed and digital images of her works for ‘books, VRs, ARs, NFTs etc’. In late 2022, the first set of af Klint NFTs went on sale via Pharrell Williams’s Gallery of Digital Assets, while Hilma af Klint: The Temple, an immersive virtual reality event accessible via an app, premiered in London during Frieze art fair in October (it allows the user to make images of her paintings bob around the room). Her spirit lingers in the digital cosmos as free-floating pixels projected onto a dingier ‘reality’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.