Oh my God, how rich and powerful Lord Channon has become! There is his house in Belgrave Square next door to Prince George, duke of Kent, and duchess of ditto and little Prince Edward. The house is all Regency upstairs with very carefully draped curtains and Madame Récamier sofas and wall paintings. Then the dining room is entered through an orange lobby and discloses itself suddenly as a copy of the blue room at the Amalienburg near Munich – baroque and rococo and what-ho and oh-no-no and all that.

Harold Nicolson was writing to his wife, Vita Sackville-West, in February 1936 after dining with the Channons: Honor and her husband, Henry, whom everyone knew by his nickname ‘Chips’, but who wasn’t Lord Channon, much as he longed to be. ‘Why am I not very very rich – and a peer?’ he asked in 1924, as a 27-year-old American recently arrived in England. He did become very rich, but continued to pine, and later to agitate, for a peerage. ‘In time I shall be Lord Chips,’ he said in 1940. But he never was.

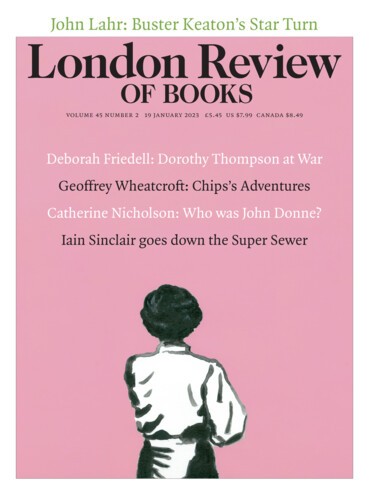

Nicolson and Channon were both published authors, both became MPs, both acquired country houses, both married the daughters of peers, both had sons but were predominantly homosexual – and both kept diaries. When Nicolson’s diaries from 1930 to 1962 were published in three volumes between 1966 and 1968 (the year he died), they were acclaimed for their inside view of political and literary life, as well as their genial urbanity and all-round good-chapmanship. This wasn’t the case for Chips. In November 1937, Nicolson writes that Channon had asked for advice about his diaries, ‘which he says he has kept at great length since 1917. He says that they are very outspoken and scandalous … He has made a will leaving them to me plus £500.’ In the end they were left to Peter Coats, Channon’s boyfriend of many years, who allowed the publication in 1967 of a drastically abbreviated and expurgated edition, incompetently edited by Robert Rhodes James, which was greeted with widespread ridicule and contemptuous comparison with Nicolson. After Coats died in 1990, the diaries passed to Channon’s son, Paul, who died in 2007. Now, with the encouragement of his children, three formidable volumes have appeared, admirably edited by Simon Heffer, with profuse footnotes displaying considerable scholarship and intermittent pedantry.

As Heffer says, Channon was seen as ‘trivial, snobbish, shallow and profoundly lacking in judgment’, a toady to the rich and royal, and, according to Nancy Mitford, ‘vile and spiteful’. But there were always dissenting voices. ‘How sharp an eye,’ Malcolm Muggeridge wrote of the Diaries. ‘What neat malice! How, in their own fashion, well-written and truthful and honest they are!’ A.J.P. Taylor said that Channon’s ‘rank highest among the political diaries of the period: written, as all good diaries should be, by a man not ashamed to own his weaknesses, it recaptures perfectly the atmosphere of the 1930s.’ Reading the two diaries long ago, I preferred Chips to Harold. There might have been an element of youthful perversity in this, but reading Channon in full and rereading Nicolson reminds me why I felt as I did.

The reception of these three volumes has been a striking contrast to the earlier edition. Nicolson today seems conventional, self-satisfied and smug, while Channon, for all his misjudgments, ingratiating behaviour and bigotry, is revealing about public and private life, society and sexuality, and honest about himself to a degree that makes these Diaries a weird kind of masterpiece. He also writes well, and the flashes of self-knowledge are of a kind never found in Nicolson:

Sometimes I think I have the character of a very clever woman – able, but trivial with flair, intuition, great good taste and second-rate ambition. I am susceptible to flattery, and male good looks; I hate and am uninterested in all the things men like, such as sport, business, statistics, debates, speeches, war and the weather; but I am riveted by lust, bibelots, furniture and glamour, society and jewels.

In November 1947, Channon dined with Somerset Maugham. ‘We discussed diaries and Willie Maugham volunteered that mine, if I presented them, would be the most illuminating. Others who keep them are too cautious, i.e. Harold Nicolson.’

Both men were born far from Westminster: Nicolson in 1886 in Tehran, where his father was a diplomat; Channon in Chicago in 1897. For years he lied about his age, until humiliation came in 1938: ‘The Sunday Express published this morning the fact that I am really 41 instead of 39, and hinted that I had faked my age in all reference books – which I fear is true.’ Although Nicolson thought his own name rather plebeian, and hoped that a peerage would enable him to change it to something more distinguished, he had the kind of background Channon yearned for: a Nicolson baronetcy had been created by Charles I, and on his mother’s side he was related to the Marquess of Dufferin and Ava. Where some people reinvent themselves to disguise a lowly upbringing, Channon tried desperately to shed his origins as the son of a rich shipowner – ‘I have put my whole life’s force into my anglicisation, in ignoring my early detested life.’ He never stopped detesting America, his home town and the parents who so generously supported him: ‘I loathe – loathe – loathe them and despise this pseudo so-called civilisation,’ and the ‘ghastly god-forgotten hole of Chicago’.

Both men went to Oxford, though in different circumstances. Nicolson had the conventional education of his class – public school and Balliol – and in 1909 followed his father into the diplomatic service, which meant that he was spared military service in the Great War. In 1919, he attended the Peace Conference in Paris with the British delegation, just after Channon had left the city. The US had entered the war in April 1917, although no American troops fought on the front line for nearly a year, and Channon never fought at all. Instead, he went to Paris with the American Red Cross and spent 1918 living in the Ritz with exiguous official duties, while plunging into the ‘Faubourg’, the last bastion of the Ancien Régime in the Third Republic: ‘Had tea with the old Duchesse de Rohan … Tea with the Duchesse de Clermont-Tonnerre in her Passy house … She is witty and wicked … a femme littéraire about whom there is sometimes unsavoury talk. But about whom is there not?’ He experienced one air raid: ‘I have never seen such an amusing night. It was filled mostly with frightened servants and some guests at the hotel half-dressed and some frankly en pyjama … Don Luis of Spain wore mauve silk pyjamas, the Duchess of Sutherland quite sleepy and bored … Winston Churchill, fat and puffy’ (he was in Paris as minister of munitions).

As battle raged in the last week of July, Channon took himself off to the Normandy coast, where he was amused to find the hotel full of ‘very young rosy-faced English officers on leave with nice young French ladies who clumsily pretend in broken English to be their wives’. This ‘bon ville’ was Cabourg, Proust’s Balbec. Channon dined with Princesse Soutzo: ‘I was between Marcel Proust and Jean Cocteau … Proust has always been kind to me and I don’t like to libel him in the pages of my diary, so I will boil down to the minimum all the rumours about him.’ Nicolson, too, met Proust, who appears in one of the pieces in Some People, a rather irritating collection of semi-fictionalised pen portraits published in 1927. Channon also formed an intense attachment to Bobbie Pratt Barlow, a rich young Coldstreamer who, Heffer tells us, was later known for his house at Taormina ‘staffed entirely by prepubescent boys’.

Channon spent most of 1920 and 1921 at Oxford, for social rather than academic purposes, but he either didn’t keep any diaries or destroyed them (‘Thank God!’ one contemporary said). He was introduced to the English aristocracy, and to European royalty. His two most adored friends – and lovers – were Lord Gage, known as George, and Prince Paul of Yugoslavia. There was also Ivo Grenfell, the third son of Lord Desborough, and Hubert Duggan, the stepson of Lord Curzon.

To accuse Channon of snobbery or social climbing is almost absurd: society was what gave his life meaning, and it’s thanks to his fascination with the rich and the grand that he left such an intimate record. The life Channon describes with such loving relish now seems as remote as Saint-Simon’s Versailles. When he wasn’t visiting country houses and playing sardines – ‘For an hour [at Hackwood] Ld Londonderry, Lady Curzon, Biddy Carlisle, Jean Norton [and] the Aga Khan lay under a very hot bed’ – there was the London Season and its gruelling round of cocktail parties, dinners, suppers and balls. Channon had the arriviste’s anxiety that he might be ‘in Society but not of it’: Derby Day was ‘a sad day for me because there is always the possibility that I shall not be invited to Derby House ball, the grandest collection of people in the world. This year I have not [been]: I am inclined to believe that it is a mistake.’

Fancy dress parties became wildly popular in the 1920s. No one enjoyed them more than George V’s eldest son, the future Edward VIII. Channon suggested to Lady Curzon the idea of a ‘n––– party’, which was apparently a great success (the redaction is Heffer’s). ‘Mr Clarkson was in attendance to blacken the faces of anyone who arrived in ordinary clothes.’ For the Duchess of Sutherland’s ball in 1923, Channon ‘went as a Bolshie with a red wig and beard. People were most caustic in their comments. Serge [Obolensky] and Bessborough were drunken waiters and upset soup and generally caused confusion before people realised who they were. The prince and his equerry, Fruity [Metcalfe], came as coolies and no one knew them and everyone was rude to him.’ Such casual racism was common at the time, as was antisemitism. In 1930, Nicolson was at Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s house when the Foreign Office nomination board was discussed, and ‘the awkward question of the Jews arises … Jews are far more interested in international life than are Englishmen and if we opened the service it might be flooded by clever Jews. It was a little difficult to argue this point frankly with Leonard there.’ Nicolson later wrote that ‘although I loathe antisemitism, I do dislike Jews.’ But Channon’s antisemitism was on a different scale. Having dined with the Rothschilds in Paris, he wonders: ‘Why cannot Jews be like other people? There was a cheap air about everything.’ Later in England, ‘the servants are casual, indeed almost rude; but this, too, is usual in a rich Jew’s establishment.’

There are no diaries for the years 1930 to 1933, but this was a crucial period in Channon’s ascent. In July 1933, he married Honor Guinness, daughter of the Second Earl of Iveagh, whose black stuff from the brewery at St James’s Gate in Dublin had made the family enormously rich. In best 18th-century fashion, Channon acquired a fortune, a house in Belgrave Square, a country house at Kelvedon in Essex and a seat in the House of Commons. Nicolson also married well, and when Vita’s mother, Lady Sackville, died, a handsome legacy came their way, which they put towards restoring Sissinghurst and creating a garden there. In 1935, Nicolson won the seat of West Leicester for National Labour, the rump that had followed Ramsay MacDonald after the Labour split of 1931. It was at the same election that Channon stepped into what was for the 20th century a most unusual pocket borough. Lord Elveden was the MP for Southend from 1918 until he became earl of Iveagh in 1927; his wife took over the seat until 1935, when it passed to Chips, until his death in 1958. (It passed to his 23-year-old son, Paul, who represented Southend West until 1997, when he was created Lord Kelvedon, the title Channon had longed for.)

For Channon, the House of Commons was a ‘club’, a ‘brown, smelly, tawny, male paradise’, and although he and Nicolson were never significant political players, both were keen observers. Nicolson became a devotee of Churchill’s, refusing to join in the chorus of praise when Chamberlain announced that he was flying to Munich. More than merely a loyal supporter of Chamberlain, Channon had succumbed to the allure of the New Order in Germany. His politics were more prejudice than principle, characterised by a horror of communism or even democratic socialism, sympathy with right-wing dictators and contempt for the poor as well as veneration of the rich and royal: ‘I am all for absolute monarchies and inquisitions and forced Catholicism.’ He had been derisive about and fearful of the short-lived first Labour government under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924, when there was ‘no quadrille d’honneur’ at the Court Ball – ‘probably it was feared the socialist ministers and their wives would be too clumsy.’ Those ministers were let off wearing knee breeches when meeting the king, except MacDonald, who was ‘very dignified and distinguished in his Privy Counsellor’s full dress uniform’. When MacDonald died in 1937, Channon said he had been happy ‘only after 1931, when he had carted his old followers, and could breathe freely the more spacious Conservative air’.

In September 1936, Nicolson met the Channons at a party in Austria. They had ‘fallen much under the champagne-like influence of Ribbentrop … They had been to the Olympic Games and had not been in the least disconcerted by Goering or Goebbels.’ This was an understatement. For Channon, watching ‘boring sports’ had only been a prelude to the appearance of ‘a large, gay, rotund figure dressed in a white uniform … It was the famous, fantastic Goering.’ Then, after the Horst-Wessel-Lied (‘which had a gay lilt’), the audience was electrified. ‘Hitler was coming! … One felt one was in the presence of some semi-divine creature: I was more thrilled than when I met Mussolini in 1926.’ On that occasion he had found the Duce ‘so like God himself’.

They had also been taken to a labour camp, which ‘looked tidy, even gay, and the boys, all about eighteen, looked like the ordinary German peasant boy, fair, healthy and sunburned … England could learn many a lesson from Nazi Germany. I cannot understand the English dislike and suspicion of the Nazi regime.’ The ‘atrocities in Germany’ caused ‘very little excitement really – the latest Jew-baiting, the beatings … who cares?’ And there was a larger moral: the fact that Germany ‘is not now communist is due to Hitler … oh! England wake up. You in your sloth and conceit are ignorant of the Soviet dangers and will not realise that … Germany is fighting our battles.’

Channon’s moment of glory arrived in June 1936, when Edward VIII – whom he had cultivated for so long as Prince of Wales – dined at his house in Belgrave Square. It was an ecstatic evening, from the royal arrival just after nine until ‘at 1.45 the king rose and I showed him to his car … it was the very peak, the summit, I suppose of social superiority, the King of England and the Kents etc to dine, to dine with me.’ (Channon was puzzled when the king said ‘I want to pump shit,’ presumably a mishearing of the naval phrase ‘pump ship’ for emptying bladder rather than bowels.)

Channon and Nicolson together give a close-up view of the abdication drama. In late October, Nicolson dined with Sibyl Colefax, Emerald Cunard and Laura Corrigan, hugely rich hostesses of a now vanished species, who devoted their lives to entertaining the London beau monde (Mrs Corrigan would give at short notice ‘a small dinner for about 120’). The talk was all about the king and Mrs Simpson, with few of those present believing that Edward would abdicate to marry her. On 3 December the news of the abdication broke. For Channon, Edward ‘could not have more clumsily mismanaged his affairs; he had only to lie, to prevaricate until after the coronation, and then all would have been well. In August next he could have married her [as] the anointed king and announced the fait accompli to a startled world and got away with it’ – which doesn’t seem very likely. Even more far-fetched, Channon tried to persuade his friend and neighbour the Duke of Kent that he, rather than his older brother, might now be called to the throne. ‘The Kents always succeed in the end,’ he told the duke, presumably thinking of Queen Victoria’s father. ‘The cunts, you mean,’ was the duke’s reply.

In March 1938, there was ‘an unbelievable day in which two things occurred: I fell in love with the prime minister, and Hitler took Vienna.’ He fell in love because Chamberlain made him parliamentary private secretary, or unpaid bag-carrier, to Rab Butler. ‘Chips at the FO, shades of Lord Curzon,’ he wrote in awed tones, unable to see that he was less Marquess Curzon than Mr Pooter. His self-importance is evident throughout the Diaries. ‘I have frustrated [Churchill],’ he wrote in July 1939. ‘He little guessed when he antagonised me what a powerful enemy I should become.’ And he has a remarkable gift for false prediction: on 24 August 1939 he wrote that ‘the whole House expects war, only I do not.’ Five days later, ‘there are accounts of the Hitler regime cracking.’ Then, on 5 May 1940, ‘I prophesy that [Chamberlain] will weather this storm.’

Channon’s mutterings seem to confirm the view that many members of the English upper class were appeasers and defeatists, if not crypto-Nazis, as does Nicolson’s comment in May 1938 after a visit to Pratt’s, the small dining club off St James’s Street: ‘I find three young peers who state that they would prefer to see Hitler in London than a socialist administration.’ But by September Nicolson reported a visit to the Beefsteak, which is, ‘I suppose, a more-or-less Tory Club, and they are all in despair about their government.’ Channon was in a different kind of despair: ‘I hate society at the moment: it is too fanatically anti-Hitler.’ He and Nicolson describe the parliamentary debates of this period from opposite sides. Nicolson remained seated while the Tories hysterically cheered Chamberlain and the Munich Agreement, but Channon was thrilled, while deriding ‘that angry bullfrog’ Churchill, and still more Duff Cooper, who had already resigned as first lord of the Admiralty in protest at Chamberlain’s appeasement of Mussolini. Channon calls him ‘a little strutting cunt-struck bantam cock’ who is always ‘trying to rape [women] in taxis’.

In his new book, Coffee with Hitler, Charles Spicer tells the story of the Anglo-German Fellowship and its secretary, T.P. Conwell-Evans.* A small number of its members were on the far right and actively sympathised with Hitler, but most, like Conwell-Evans himself, were pacifistic idealists. No such excuse can be made for Channon, whose susceptibility to the Third Reich went beyond naive delusion. Or, as the travel writer Robert Byron said to him, ‘the trouble with you, Chips, is that you put your adopted class before your adopted country.’

After Chamberlain gave his guarantee to Poland in March 1939, and even after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact opened the way for the German invasion of Poland, Channon still hoped for peace and was angry when he visited the Foreign Office on 2 September to find it ‘in a state of funk lest they should not have their pet war’. The same day, Chamberlain said that unless the German army withdrew it would mean war. ‘Broken-hearted I begged David Margesson to do something but he was determined. “It must be war, Chips, old boy.”’ When the declaration came the following morning, Channon felt that ‘our old world or all that remains of it, is committing suicide, whilst Stalin laughs.’

But for the eight months of the phoney war, Channon’s life stood still, and when he wrote of ‘the end of an epoch’ in February 1940 he was referring to the fact that Lady Cunard ‘has left 7 Grosvenor Square and taken refuge at the Ritz’. He knew that ‘Winston dislikes me intensely and shows it,’ but, although he realised that Churchill was ‘determined to reach Number Ten’, he believed ‘it would be but for a brief reign.’ Not that imprescience was his alone. As late as 1 May, while the lamentable Norway campaign unfolded, a colleague told Nicolson that if Norway was lost, Chamberlain would have to resign, but Nicolson said: ‘The PM will stay put.’ The next day, Channon was ‘reluctantly realising that Neville’s days are, after all, numbered’.

When the Norway debate took place in the Commons on 8 May, Nicolson saw how much Chamberlain had damaged himself by personalising attacks on the government, saying, ‘I have friends in this House’ with ‘a leer of triumph’. At the end of the debate, Churchill made what Channon calls ‘a slashing, vigorous speech, a magnificent piece of oratory’, ostensibly defending the government and the Norway campaign, for which, as first lord of the Admiralty, he bore much responsibility. Dozens of Tory as well as Labour MPs voted against Chamberlain. ‘“Quislings” we shouted at them,’ Channon wrote: ‘“Yes-men” they retorted.’ On 10 May, when Chamberlain resigned and Churchill became prime minister, Channon noted: ‘England in her darkest hour has surrendered her destiny to the greatest opportunist and political adventurer alive!’ All he can do is open a bottle of Krug 1920 as he, Butler, Alec Dunglass and Jock Colville, ‘four loyal adherents of Mr Chamberlain’, drink ‘to the king over the water’.

During the first eighteen months of the war, Channon travelled twice to Yugoslavia – whose prince regent, Paul Karadjordjević, was his old Oxford friend and ‘the person I love the most in all the world’ – with the approval, if not the encouragement, of the British government. In March 1940, the journey could still be made through France and Italy, but in January 1941 it meant a circuitous route by flying boat to west Africa and then Khartoum and Cairo before flying to Greece and taking an uncomfortable train to Belgrade. He saw Paul, but to no political or strategical end: by that spring, Hitler’s attention was being drawn unwillingly to the Balkans, where he had to come to the rescue of Mussolini. At first the prince regent told Hitler that he didn’t want his country to be used by the Germans to attack Greece, which was his wife’s country, but in March 1941 the Yugoslav government signed the Axis Tripartite Pact and the prince was deposed by the army. He escaped but was interned by the British in Kenya for the rest of the war while his country was occupied and torn apart.

In London, a government reshuffle in July 1941 left both Channon and Nicolson out of a job. Nicolson received a cool letter from Churchill relieving him of his junior ministerial office and offering a place on the board of governors of the BBC. He was full of woe: ‘Ever since I have been in the House I have been looked on as a might-be. Now I shall be a might-have-been.’ Channon wasn’t even a might-have-been, just a sharp eye and sharper tongue. But he dreamed of higher office, failing to grasp that he bore the mark of Munich, made worse by his friendship with Prince Paul, who was now damned, not quite fairly, as a near-quisling. In any case, no one but Chips himself ever took him seriously as a political figure. Social life continued, and rationing doesn’t seem to have troubled Channon or his friends, on whom the war itself often had little impact. When in July 1943, after the Allies had driven the Axis out of North Africa and crossed the Mediterranean, Channon said to Laura Corrigan, ‘Isn’t it wonderful about Sicily?’ she replied: ‘Sicily who?’

One difference between the two diaries is particularly striking: Nicolson writes about people with almost exaggerated politeness, while Channon lets rip. The socialite Maureen Stanley is a special object of his loathing. In the entry when he learns that she is ‘desperately ill and may die’, he adds: ‘I most certainly hope so.’ She is ‘a vampire, nymphomaniac, a drunkard’. Having heard that ‘His Grace of Wellington’ might be involved in the 1954 Montagu case – when Lord Montagu was convicted of homosexual offences – he commented: ‘If that ponderous old poof got involved in a scandal it would be diverting for many people’ (he wasn’t involved). Nothing brings out his vitriol more than a death. When Basil Dufferin is killed in Burma, it’s for the best: he was ‘drunken, diseased, hopeless and feckless’. Duff Cooper was ‘devoid of heart, kindness, charm, integrity, even good ordinary manners, he somehow bluffed his way through life and succeeded.’ And so on.

‘I do not think it right to record day by day all the turpitude or sexual aberrations of my friends,’ Nicolson says with characteristic pomposity. It wasn’t until 1973 that Nigel Nicolson, his son and the editor of his diaries (another man hated by Channon), published Portrait of a Marriage, which revealed that both his parents’ sexual interests lay outside the marriage. Vita had a series of liaisons with other women, and Nicolson ‘was himself’, as the ODNB says, ‘by no means a stranger to homosexual affairs’. None of this is hinted at in his diaries. When, for example, Nicolson writes in 1945, ‘I dined with Guy Burgess who shows me the telegrams exchanged with Moscow,’ there is no suggestion either that he knows anything of Burgess’s work as Soviet agent, or that they were bedmates.

By contrast, Channon’s account of his and others’ sex lives is jaw-dropping. In 1956, he went to Holkham Hall in Norfolk for the wedding of Lady Anne Coke to Colin Tennant, later Lord Glenconner. In her recent memoir, Lady in Waiting, Anne Glenconner describes her husband’s sexual proclivities, but also says that in those days girls of her class couldn’t possibly sleep with men before marriage. That is not what Channon’s pre-war account of other earls’ daughters suggests. In 1925 he visited Madresfield Court in Worcestershire, seat of Earl Beauchamp, with its ‘brood of lustful Lygons, lovely of feature and steeped in every vice … There are prayers twice a day and the girls, with whom one is later to sleep, look like angels singing in exaltation, so innocent are their expressions.’ One of them was Mary Lygon, who came to lunch in January 1935, ‘looking as pretty and as peach-like as ever … so surprised and innocent and yet, I suppose, she has slept with every man one knows in London.’ If Channon has an affinity with Proust, it’s not so much in his fascination with the haut monde as his all-absorbing interest in sexuality, especially homosexuality. (Of Proust, Channon wrote: ‘I knew him more intimately than I have confided in this diary.’)

For years, Channon enjoyed what he called ‘two-way traffic’. He describes a visit to a ‘little tart in Orange Street’: ‘I then wreaked my lust on her, undisturbed by her Northumbrian accent.’ Having dined with the Duff Coopers in 1935, he noted ‘at that little table were many of the people whom I have loved mentally, and some physically.’ Two years after their wedding, the Channons’ only child, Paul, was born, but eighteen months later ‘we broke off conjugal relations, never in our case particularly successful.’ By then Honor was increasingly absent on supposed skiing holidays – one of them in July – and Channon eventually realised that she was having an affair with a skiing instructor, then another with a Hungarian nobleman. Finally she left him, and went off with ‘a dark horse-coper named Woodman’. Evelyn Waugh heard a fictional echo – ‘Lady Chatterley in every detail’ – although Channon thought it more Far from the Madding Crowd: ‘She is Bathsheba, Sergeant Frank Troy, Mr Woodman.’

In 1938, Honor’s sister Patricia married another Tory MP, Alan Lennox-Boyd. From this point, the Diaries give an unmatched account of clandestine queer life in that era. Channon developed a passion for having a ‘Turker’ or Turkish bath, not always for the purpose of losing weight. At the Royal Automobile Club there were private cubicles. ‘Alan and I had a Turkish bath at the RAC. He talked too loudly and is indiscreet politically and sexually.’

Before long, the brothers-in-law were sleeping together, as well as enjoying their own adventures and coups de foudre. At a dinner party in July 1939, Channon met Peter Coats, a ‘pierrot of … Aryan good looks … charming and gay’, who worked in advertising although he later became a gardening writer. He was known as ‘Petticoats’. (Before and after the war Channon still uses the word ‘gay’ in its older sense, but from around 1950, before it entered wider parlance, he uses it to mean homosexual.) Soon afterwards the two met again at a ball at Blenheim Place, and before long their liaison, what Channon calls their ‘axis’, was firmly established, although it was interrupted when Coats, a Territorial Army officer, was taken away by military duties. By February 1940 he had ‘the plum job in the whole army, ADC to the General of the Eastern Command, Sir Archibald Wavell’. On his way to visit Paul in Belgrade, Channon flew to Cairo: ‘From the window before we landed I saw Peter, brown, amber, alert, handsome, distinguished, stupendous, waiting for me.’ Channon found that ‘the Cairene scene is just my affair, easy, even elegant, corrupt, luxurious, trivial, worldly, me, in fact.’

One of his circle was Paul Latham, an extremely rich baronet and Tory MP who was serving in the army. Their friendship survived Latham’s warning that Coats was on the make. In June 1941, it was reported that ‘Latham has had an appalling crash on his motorcycle,’ but it transpired that the crash was an attempted suicide: he had been arrested and was being court-martialled for a number of sexual offences with his own men. He was sentenced to two years in prison. While noting that ‘the Latham case is a revolting one and the details too squalid for description,’ Channon couldn’t resist adding that when ‘the news reached the Ritz Bar’ – evidently a cruising joint – it caused such consternation that it ‘emptied in five minutes’. But he was indignant at the general response: ‘A wall of anger and filthy gossip has swept over London. Heresy-hunting and talk of “purges”: one might be living in the Wilde period.’

Having already been to see Flare Path by the young Terence Rattigan, in March 1944 Channon met ‘Mr Rattigan … chez Sibyl Colefax. Il en est ainsi [he’s queer] and a dull fellow.’ In September, Channon described him as ‘a pretty pink and white youth, gay and gracious … this very good-looking lad, who seems even younger than his 33 years’. Coats was in India, and before long Channon was infatuated with Rattigan. Noël Coward told Channon that the ‘alliance’ was ‘one of the romances of the century’. After ‘our honeymoon’ in Brighton in January 1945, Channon showered Rattigan with gifts. His Diaries are a catalogue of Fabergé trinkets, bibelots and jewellery, given by men to women and by men to men. A ‘parure’ usually means a woman’s set of tiara, necklace and bracelet, in matching rubies or emeralds. I haven’t seen it used of menswear before. Channon is forever exchanging jewelled cufflinks or parures, by which he means matching links and studs for a shirt front. In 1952 he met Prince Paul in Paris: ‘He looked splendid; so did I as I was wearing the ruby-and-diamond parure that he gave me in 1939.’ After their romance came to an end, Rattigan gave a party where Channon found him wearing ‘my shirt, my sapphires, my wristwatch and cigarette case – all of which I had given him’.

Channon was warned by John Gielgud that his liaison with Rattigan was all too public, while Nigel Birch, a clever, sarcastic Tory MP, teased him about the silk shirt he wore with the embroidered initials ‘TR’. Channon was acquainted with Lord Berners and ‘his crazier catamite, Robert Heber-Percy’. He writes of Berners attending a wartime ‘dinner party at Emerald’s … where the conversation was mighty scandalous; added that my name was being bandied about, bracketed with Terry!’ Berners feared ‘a puritanical revival after the war as a reaction against the general loosening of morals which has undeniably taken place’.

At the 1945 election, Channon’s poster read: ‘Vote Channon the Loyal Supporter of Churchill’, which took some nerve. In the Diaries he quotes what he had heard was an unpublished entry in a New Statesman competition: ‘The solution/Is revolution./But that would be hard/On Lady Cunard!’ On VE Day, he gave a large party: ‘Sibyl Colefax and Harold Nicolson, the Londonderrys came,’ as well as Coward, Frederick Ashton and Lady Cunard. ‘Why did I go to that party?’ Nicolson wondered. ‘I loathed it.’ There were gathered all ‘the Nurembergers and the Munichois celebrating our victory over their friend Herr von Ribbentrop.’ To make it worse, Channon survived the Labour landslide, while Nicolson lost his seat. (In 1948 he stood as the Labour candidate in the North Croydon by-election, which he lost soundly, not that he minded too much: ‘I should not like to represent Croydon, which is a bloody place.’) Channon, meanwhile, had decided that ‘I will call myself Lord Kelvedon’ when ennobled (‘but it’s not in the bag yet’).

Channon continually damned people for being ‘common’, from the Duke of Wellington to Lady Geddes to the Prince of Wales. ‘How common are the new duc et duchesse de Noailles,’ he wrote, and also: ‘I finished a foolish second-rate novel, The Easter Party by Vita Sackville-West; appalling, common and inaccurate.’ An acquaintance was ‘very common naked, which is such a test’. (But that’s almost preferable to Nicolson saying: ‘We are humane, charitable, just, and not vulgar. By God, we are not vulgar!’) More than almost any of his contemporaries Nicolson personified the establishment – as distinct from Channon’s milieu, which was high society – and was at the heart of it all his life. For all of his lucrative marriage and his courtship of the grand and royal, Channon remained in many ways an outsider. Nicolson was so much a man of the establishment that he was asked to write the official biography of King George V, which earned him admiring reviews, huge sales and KCVO, the knighthood in the personal gift of the monarch.

When, in November 1947, the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Philip of Greece brought an array of royalties to London, Channon gave a dinner party at which the ten guests included the queens of Spain and Romania, even if neither then reigned in her country. ‘People gasped at the splendour which one rarely sees nowadays,’ Channon reported, and Somerset Maugham whispered to him: ‘This party is the apogee of your career!’ ‘Really I am only at home with royalty,’ Channon wrote, but his reverence never inhibited his bluntness, or malice. George VI is ‘completely uninteresting, undistinguished and a godawful bore!’

Months after the wedding, Channon reported that ‘Philip Edinburgh, although as always extremely handsome and pleasing-looking, appeared ill, wan and “shagged out”!’ His wife is ‘well meaning, but already a little pompous and a bore’. She and her even shorter sister, Margaret, were known as ‘Lilibet and Lilliput’. Before Elizabeth’s coronation, Channon wrote that ‘conversation has taken a Gilbert and Sullivan quality. Coaches and robes, tiaras and decorations. Winnie Portarlington announced at lunchtime that she has harnesses but no coach; Edie Londonderry has a coach but no horses; Mollie Buccleuch has no postillions – but five tiaras.’

Apart from complaining about the Labour government’s ‘wicked’ taxes, Channon’s attention to politics flagged in the postwar years. He was angry when the Commons voted to suspend capital punishment in 1948. Supporters and opponents of hanging were called ‘Drops and Drips’, and Channon was an ardent Drop, who shocked even Quintin Hogg by saying that public execution should be brought back. He was able to report subsequently that the Lords had not only overturned the Commons vote but ‘slipped in the birch; peers are always, rightly, keen on whipping.’ He certainly was himself: ‘I should love to be beaten by a priest or schoolmaster and never have,’ he laments. In 1942 he had visited the Benedictine monastery at Buckfast and was excited to learn that ‘the monks are all flogged on Fridays … I must try to see that,’ or again: ‘I would have done anything, given almost anything, to be taken into the woods, stripped and whipped by a fat middle-aged severe woman … such strong impossible desires. Do all men have them?’

The Channons finally divorced, and Chips won custody of their son, Paul, who had been sent to America at the beginning of the war. Channon’s love for his son is one of his redeeming features, and Paul had what was then the unusual experience of being in effect brought up by a same-sex couple. After Channon’s ‘divorce’ from Rattigan, he lived with Coats for his remaining years. He was anything but faithful. On the contrary, his enthusiasm for what he called ‘philandering’ and ‘fornication’, or ‘voluptuous sport’, only increased. ‘I am in riotous health, bronzed as a Bedouin and all my appetites, gastronomic and sexual are colossal,’ he writes. ‘I am very sexual at the moment … I am frittering away the hours planning infidelities.’ He finds time for ‘a romantic rendezvous’ with a new young man, slipping away from the Commons to ‘his squalid lodgings … for an hour’. Then it is ‘mortal sin about 5.10’. He ‘played “hookey” from the House and behaved badly’. The next day, he wrote: ‘Tout m’ennuie except when I feel well and ripple as I have done all day – one always does after sex!’ Even when he goes to Oxford for a Christ Church gaudy he wanders off and has ‘an adventure’. ‘Dined at Pratt’s and later “frolicked” … An exhilarating adventure and rencontre in Trevor Square … I behaved wildly, viciously, excitingly. Vice, vice, vice … Vice unashamed.’ Another companion ‘sated my lust most delightfully’, although the next day ‘my right nipple bleeds a little from last night’s excess.’ Watching the Life Guards on parade, Channon is delighted to see ‘Corporal Douglas Furr, my private friend’. The only thing that gives him pause is when he takes Nigel Davies, a Tory MP, to ‘a Boy’s Ball where everyone was dressed as animals’ and wonders: ‘Is this Byzantium? The end, the eclipse of the empire.’

Channon notes ‘what a nice man’ David Maxwell Fyfe is, and comments, with his usual gift for dud prediction, ‘he will go to Downing Street, certainly.’ It was Maxwell Fyfe who, as home secretary from 1951 to 1953, told the Commons that ‘homosexuals, in general, are exhibitionists and proselytisers and a danger to others, especially the young.’ Channon records his dismay when, in 1953, John Gielgud was arrested for importuning. His friend Edward Montagu was acquitted of offences with a boy scout but Channon noted

an uneasy undertone à propos of the Gielgud and Montagu cases … There is, it seems, a witch-hunt against ‘perversion’ etc. Certainly several people have behaved squalidly and stupidly recently but that is no real reason for a drive, or crusade, and in years to come people who lead it will look as foolish as do the witch-hunters of ancient days.

‘The socialists, too,’ he wrote, ‘are perturbed by what amounts to a persecution of Edward; and they would welcome the relaxation of the law, ridiculous and out of date as it is.’ But his indignation didn’t prevent Channon from enjoying ‘another riotous evening of Bacchanalian fun. Games. Charades. Mary Lee Fairbanks and I won; we acted Edward Montagu and the boy scout!’ The following year, Montagu was prosecuted again, and this time imprisoned. Channon died in October 1958, just before the downfall of Ian Harvey, another Tory MP, who was arrested in St James’s Park with a Guardsman.

After ‘Tout m’ennuie’ there’s a footnote translating it, as there is for every one of the French phrases with which Channon sprinkles his text, some of them unusual idioms, some familiar. Heffer is a self-proclaimed linguistic stickler, but he isn’t always quite right, either in French – ‘petit maître’ has several nuances of meaning, but ‘young master’ isn’t one of them – or in English. When Channon reports that ‘Russia is denouncing her nonaggression pact with Japan,’ a footnote says: ‘He means “renouncing”.’ No, he doesn’t: in diplomatic usage, a treaty is denounced by a party withdrawing from it. When Channon is driven home by ‘John Hare (and what a Jehu he is)’ a footnote tells us merely that ‘Jehu was a king of Northern Israel in the ninth century BC; he conspired against his predecessor.’ The allusion is to the verse ‘the driving is like the driving of Jehu the son of Nimshi; for he driveth furiously.’ When Channon says that Princess Marina ‘always is a stranger here – a royal Ruth in the alien corn’, the footnote says: ‘He refers to the Bible and the Book of Ruth, who picked up pieces of corn missed by reapers in order to feed herself,’ when Channon plainly intends Keats’s ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, and ‘the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home,/She stood in tears amid the alien corn.’ Chips might not have minded that, but he would have been shocked at the Dramatis Personae managing to confuse two duchesses of Buccleuch. But for all these cavils, the editing is a remarkable achievement. Heffer acknowledges the help of Hugo Vickers, a walking Almanach de Gotha, and the footnotes explaining every person mentioned constitute a work of scholarship in themselves.

Reading these Diaries is both absorbing and time-consuming, not least because they lead the reader down so many interesting byways. In June 1951, Channon reports from the Commons that ‘Michael Foot, a real horror of the French Revolution type, made a vindictive, violent speech about Northern Ireland.’ It proves, on reading it in Hansard, to be an excellent speech criticising the treatment of Ulster Catholics as second-class citizens, contradicting the widely held belief that Northern Ireland was forgotten by Parliament and people during the half-century of Stormont.

Did Channon expect his diaries to be published? Unlike Nicolson, who wrote with the half-conscious caution of a man who had that in mind, Channon wrote with a complete indifference to respectable opinion or any imaginary reader. He must have known that, had his enthusiasm for the Third Reich been public knowledge, he might have been interned in 1940 like another Tory MP, the ferociously antisemitic Hitler-worshipper Archibald Ramsay, or that if his ‘adventures’ had been generally known he might have been imprisoned like his friend Latham. Or maybe not. In 1952 Channon wrote that Lennox-Boyd’s appointment to the privy council had been held up ‘because of rumours about his morals: he thinks that WC will never consent to give me anything either.’ But Lennox-Boyd would soon join the cabinet, and became a peer in 1960. And many people accepted Channon and Coats as a couple, as testified by the hundreds of letters of condolence Coats received when Channon died. ‘Everyone is a knight of some sort except poor me,’ Channon had written plaintively in 1954. ‘I thought it infra dig to be a knight; sounds like one’s dentist or surgeon; but now, if offered a knighthood, I would not refuse. One must cut one’s losses.’ It came in 1957, the year before he died.

Once, travelling back from Southend, Channon ‘discussed myself with an unknown man on the train who was unaware of my identity. He said that I was known as being “democratic” and “not a snob” etc in my constituency. I was tempted to get him to put this unorthodox, rather startling, view on paper – since obviously no one would believe the story.’ It’s hard to imagine Nicolson saying anything like this, and Channon would never have said of himself as Nicolson did: ‘God knows that my integrity is a solid thing with me. I am unambitious and devoted. I really am.’ On the contrary, Channon was ready to admit that ‘I have no morals, no ideals, no principles whatever – except that of good manners – and have had a most enjoyable life.’ It’s this self-awareness that makes the Diaries so readable. And of course the gossip related with such glee: ‘King Ghazi of Iraq was killed by a motor car. He is unlucky with motoring since his chauffeur gave him clap only recently.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.