Well, I could never write a verse, – could you?

Let’s to the Prado and make the most of time.

Robert Browning, ‘How It Strikes a Contemporary’

The world has an established place for poems about paintings – sometimes you wonder if there was ever a poet who didn’t write one – but, oddly, the poem-painting relationship doesn’t seem to be reversible. Or only in ways that miss the main point. Poems about paintings most often circle round the ‘about’ in the exercise, and are fired by an awareness of how strange it is even to want to transpose the procedures, the effects, of one art into another. Isn’t what Bruegel and Velázquez did untranslatable? Surely painters are bent on communicating things – ideas, experiences – that words will never touch? But precisely that fact is the spur to poetry. Silence and self-evidence make a space for language; a painting’s semantics of juxtaposition and interval, the poet says, may trigger a kind of syntax no one has tried before; the all-at-onceness of the image is an incitement to prosody. Why then, conversely, are not paintings drawn from Paradise Lost or Marino Faliero driven by a similar effort at mimicry, or intimation at least, of Milton’s or Byron’s extraordinary diction?

I’m not sure why. There is no shortage of paintings derived from verse, often importing material (even mood and atmosphere) directly from the text – ut pictura poesis was always meant to work in two directions – but there don’t seem to be many paintings that are ‘about’ the poem that sparked them in the same way that a good poem is about the painting in front of it. Depictions with poetic starting points, that is, are not necessarily concerned with the ‘poetic’, or even the linguistic. They do not set themselves to wondering in visual terms what poetry really is – what marks it off from depiction. No doubt many painters appreciate that poetry has to do with some kind of special balance, or imbalance, between the materiality of meaningful sound and the intensity of whatever it is (the state of affairs, the realm of feeling) the sound means to materialise. But this isn’t painting’s business. Painting needn’t envy, painters seem to feel, still less try to borrow, what belongs to another way of world-making. Even Blake does not brood on the two arts of which he is master, or not as rivals or Siamese twins.

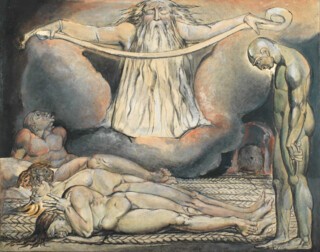

When he works over a horrifying passage from Paradise Lost, for instance, in the series of pictures he made of The House of Death, Blake seems focused on making Milton’s picture of God’s mercilessness as horrifying in the media of chalk, ink and watercolour as he found it in Book XI’s blank verse, not with what horror in poetic language might be as opposed to horror in a visualisation. Milton’s God is unforgivable in his abstractness, his weddedness to the Word; Blake’s by his concreteness, his symmetrical heartless beauty. The closest you get in the watercolour to the question of language is God’s loving hands on the scroll: ‘It is written.’ But writing invades the picture no further. It is overtaken by God’s great waterfall beard, by the bodies below, locked in the private language of pain. And Blake’s painting in general, it seems to me, is as little concerned to be like the poetry it usually accompanies (his own poetry, in other words) as that poetry is to be visual, if we mean by visual full of particularised descriptions, observations. Blake the poet is unobservant. His poetry has other purposes. It has no time to stop and dilate. (As for Marino Faliero, it seems to have been to Delacroix’s advantage as a painter that he was innocent of Byron’s ironies. Poets for him were providers of extremes.)

Writing poems about paintings is a thing poets regularly do, then, and many times do well; but it is difficult, and potentially a trap. Ekphrasis in particular – going in for a full-scale rehearsal of a (real or imaginary) picture’s form and content, trying for a wholesale transposition, a verbal equivalent – is very often the shortest way to a non-poem. The absence of poetry in such cases seems indistinguishable from, is perhaps caused by, the almost universal absence of the picture in the final ekphrasis, for all the effort to have it be present. There may be something wrong with the set-up. A picture and a poem can’t approach each other face to face, competing for attention or pretending to be completely at each other’s service.

Poets who care intensely for paintings can be wary of writing about them. The greatest poet to have put the cult of images at the heart of his poetics, Baudelaire (‘Ma grande, mon unique, ma primitive passion,’ he called it) wrote an anti-ekphrasis on the subject. ‘Les phares’, the poem says (lighthouses, pictures by Rembrandt and Goya and Delacroix), are designed to be seen from afar. What matters is the beam, the pulse in the darkness. We don’t need a description of mirrors and brickwork (still less the lonely life of the lighthousekeeper).

Let’s start at the top. Zbigniew Herbert was a poet whose whole sense of life surely turned on a passionate engagement with the plastic arts – with the Greek achievement, with the immense middle road laid out by the Dutch in the 17th century. When he first saw the canvases of Jan van Goyen, he tells us,

I felt I had waited an age for just this painter, that he filled a gap in the museum of my imagination I had sensed for a long time. It was accompanied by an irrational conviction that I knew him well and for ever … A road through a village, a ferry floating down the river, a hut among dunes – these are the typical subjects of Goyen’s paintings … Often the topography of his works isn’t clear: somewhere beyond the dune, on the bank of some river, at the turn of a road, on a certain evening … Canvases with no anecdote, loosely composed, flimsy and slim, with a weak pulse and nervous outline, they quickly leave their imprint on the memory. The eye assimilates them without any resistance … It was said he had the cheapest elementary props you can imagine in his studio: clay, brick, lime, pieces of plaster, sand, straw. From these leftovers, rejected by the world, he created new worlds.

A world composed of leftovers. We have the makings here, I think, if we put these sentences alongside, and in tension with, an equally typical Herbert tribute to the landscape at Delphi or the rustle of Apollo’s stone robes, of the inimitable mixture of weakness and strength, the throwaway and the lapidary, in Herbert’s poetry. Weakness is precious. Cheap props are indispensable. Ordinariness is part of greatness. Yet van Goyen – and Dutch art in general – never appears in a Herbert poem.

The same goes for the Italian painters closest to his heart: ‘I lived then in the throes of a passion for Altichiero/of the San Giorgio Oratorium in Padua.’ This is confessed in a tremendous poem called ‘Rovigo’. We have a prose fragment explaining the passion:

The whole business borders on a scandal. With the exception of a few specialists, virtually no one knows Altichiero’s name, and it is difficult really to say what is the reason for the neglect.

It may be because the corpus of his works is small, or because he worked as if in the shadow of Giotto’s powerful personality. Whatever the causes, we must finally break the conspiracy of silence.

Giotto stems entirely from the Franciscan spirit … the somewhat sweet, feminine spirit of the Poveretto. Altichiero on the other hand comes from the spirit of Dante – stern, knightly, metaphysical.

It often happens that a great discovery in the sphere of art history is the work of writers, not art historians … [He is thinking of Thoré-Bürger’s discovery of Vermeer.]

I have tried my strength so that Altichiero might finally be granted his proper place among the most excellent of artists.

But not in poetry, it turns out. Poetry must be prepared to pass its heroes by. The subject of the poem in which Herbert’s passion for Altichiero is mentioned is not the painter or his work, but a small town a few miles south of Padua. ‘Not marked by anything in particular/it was a masterpiece of averageness straight roads/ugly houses,’ a train stop at which Herbert never alighted. The poem, which builds characteristically from weakness to strength, ends by centring on the irreducible unknown lives that Herbert imagines, ‘a city where a man died yesterday someone went mad/someone coughed hopelessly all night’:

depending on the train’s direction

just before or just after the city a mountain suddenly

rose up from a plain cut across by a red stone quarry

like a holiday cut of meat draped in sprigs of parsley.

‘Canvases with no anecdote, loosely composed, with a weak pulse and nervous outline’. In ‘sprigs of parsley’, deliberately courting the risible.

The tone of ‘Rovigo’, to put it another way, is about as far from ‘About suffering they were never wrong,/The Old Masters’ as poetry can get, though the poem’s subject is roughly the same as Auden’s. And the tone is only achievable if one writes out the Altichiero – the knightly and metaphysical – in one’s makeup. Sometimes the best use of a passion for a painter – a passion for something only a painter can do – is to purge a poet of the wish to aim high.

Perhaps it is easier for poets to write directly about paintings if they do not care about them too much. Nothing in the mass of John Koethe’s verse and philosophical prose, for instance, suggests that paintings haunted him continually in anything like the way they did Herbert. (If I do him an injustice, I apologise.) But this seems to have meant that when he spent an hour or two with the Masaccios in Florence, he could seize on the Expulsion from the Garden of Eden as he would on any sudden charged episode passing by in life:

In Masaccio’s fresco in the Brancacci Chapel

The figures are smaller than you’d expect

And lack context, and seem all the more tragic.

The Garden is implicit in their faces,

Depicted through the evasive magic

Of the unrepresented. Eve’s arm is slack

And hides her sex. There isn’t much to see

Beyond that, for the important questions,

The questions to which one constantly comes back,

Aren’t about their lost, undepicted home,

But the ones framed by their distorted mouths:

What are we now? What will we become?

This is wonderful because so incomplete. It is a philosophical poet taking advantage of Masaccio – taking a lesson from him – and not being in the least embarrassed by the way a train of thought, a feat of language, overtakes the matter of seeing. ‘There isn’t much to see/Beyond that’ would no doubt have had Zbigniew Herbert snorting; but the poem – the saying and seeing as much as Koethe does – depends on it.

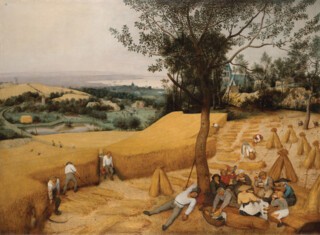

Even poets who in theory stake everything on poetry attaining to the condition (the concreteness) of the visual – I think of William Carlos Williams – find that when it comes to writing about the images they admire most the task ends up destroying their parti pris. ‘No ideas but in things’ is the war cry. Bruegel is chef de file. But the best poem in Williams’s collection Pictures from Bruegel is the one about the Prague Haymaking; or rather, about Haymaking oddly crossed – in memory, it seems – with The Harvesters in New York, which was a Williams touchstone. And of all the poems in the sequence this is the one that struggles most bafflingly, most discursively, to mimic the play of mind – the more-than-concreteness – that makes a Bruegel painting what it is. Of course, ideas and things do stand, in Bruegel, in an inimitably close relation. But the word ‘in’ won’t do (any more than the ‘about’ of ‘about suffering’) to sum the relation up.

The living quality of

the man’s mind

stands outand its covert assertions

for art, art, art!

paintingthat the Renaissance

tried to absorb

butit remained a wheat field

over which the

wind playedmen with scythes tumbling

the wheat in

rowsthe gleaners already busy

it was his own –

magpiesthe patient horses no one

could take that

from him.

What is it that belongs to Bruegel in the painting, and what to the wheatfield? That seems to be Williams’s question. What is it that art can assert only covertly? And why? Who or what is the ‘no one’ in the poem’s last verse? (He, she or it stands ready to take what is Bruegel’s ‘own’ away from him – though Bruegel fends off the burglar. So what is the burglar after, exactly?) The poem’s grammar seems to assert that the painting itself is the wheatfield. Does this mean the field, the wind and the men with scythes are not ‘things’ after all, but metaphors for Bruegel’s turn of mind? You look back to the New York picture and think perhaps they could be. The shape of the wheatfield there is hard-edged, elaborate, abstract – wheat is already a commodity. I don’t see a wind disturbing things, but many other forces in the picture put the field’s perfection in doubt: the foreground tree, the guzzling peasants on their sofas of straw, the fabulous sprawling sleeper, the game being played on the far village green. And the questions the poem ends up asking of these oppositions are as philosophical and mind-and-language-centred, the reader comes to realise, as any of the bad Ideas (the Renaissance categories) they claim to be launched against. The poem’s final stanzas are pure dialectic. Magpies fly in from nowhere and vanish. The short lines and weird line breaks keep everything in suspense. Their deadpan argumentativeness is Bruegel to a tee.

Most poems that don’t do justice to the paintings they praise are best passed over in silence, but there are exceptions. Wallace Stevens’s ‘Angel Surrounded by Paysans’, for instance. French painting had always been a touchstone for Stevens – Picasso is a repeated figure in the margins of his early poetry, Cézanne’s letters a key point of reference – and in the years following the Second World War he made the allegiance explicit. It seems 1949 was a special moment. Stevens did a catalogue essay for a show in New York of Marcel Gromaire. ‘Look at his pictures as they are,’ he wrote,

heterodox, slightly grim (an orthodox element in anything intended to be social comment), dense in colour as becomes a Goth, rugged with realism, uncompromising, in the idiom of Verhaeren, endowed with the strength that comes from participation in life’s struggle … things not of the school of Paris, but of some harsher, more fundamental zone.

A passion for painting can lead a poet to admire an aesthetic very unlike his own.

Then, in September 1949, Stevens took delivery of a still life by the Breton painter Pierre Tal-Coat. Almost immediately he told Paule Vidal, who had arranged the purchase, that he had christened the painting Angel Surrounded by Peasants; and then a few days later he mentions a new poem titled ‘Angel Surrounded by Paysans’ (the change of language in the last word is not a good sign). ‘The angel is the Venetian glass bowl on the left with the little spray of leaves in it. The peasants are the terrines, bottles and the glasses that surround it. This title alone tames it as a lump of sugar might tame a lion. I shall study everything that I see concerning Tal-Coat.’

Taming, alas, is about right. The Venetian glass angel speaks in the poem as follows (I have chosen its least abstract lines):

I am one of you and being one of you

Is being and knowing what I am and know.Yet I am the necessary angel of earth,

Since, in my sight, you see the earth again,Cleared of its stiff and stubborn, man-locked set,

And, in my hearing, you hear its tragic droneRise liquidly in liquid lingerings,

Like watery words awash.

This is very painful. It is as if the Tal-Coat painting had to be cleared of its slapdash man-made things – its terrines, the clumsy cloth laying hold of the table, its sour green wallpaper, the glass half-full of glinting wine – in order for an angel’s-eye view to replace it: all sight, all assonance and liquidity. You wait in vain for the salving Stevens moment, when the Imagination turns a corner and collides with the Man on the Dump.

How much more of an homage – how much more of a poem – are the few lines Stevens writes to Barbara Church a fortnight later:

My Tal-Coat occupies me as much as anything. It does not come to rest, but it fits in. Raymond Cogniat speaks of [Tal-Coat’s] violence: that of a Breton peasant from the end of the earth (Finisterre). It is a still life in which the objects are a reddish brown Venetian glass dish, containing a sprig of green, on a table, on which there are various water bottles, a terrine of lettuce, a glass of red wine and a napkin. Note the absence of mandolins, oranges, apples, copies of Le Journal and similar fashionable commodities. All of the objects have solidity, burliness, aggressiveness. This is not a still life in the sense in which the chapters of de Maistre are bits of genre. [Stevens had been reading Voyage autour de ma chambre.] It is not dix-huitième. It contradicts all of one’s expectations of a still life and does very well for me in the evenings when its vivid greenish background lights the lights, to make the most of it.

‘It does not come to rest.’ It is not cleared of its stiff and stubborn objects.

Going further with this topic means reflecting on my stake in it. I have spent a lot of my life writing prose about paintings, and then occasionally, particularly in the past couple of decades, poems. Why the poems occurred, and how what they have to say about paintings differs from a prose description, isn’t clear to me. A poem written recently about Cézanne’s Hillside in Provence begins:

Everything in a picture is turned to face us,

But in a good picture the turning is done with tact,

Almost reluctantly, so that we see a kind of shadow world –

Shadows softer and brighter than the things that cast them –

Standing next to the trees come forward to meet us, made from

Objects we sense as much as see, forms not belonging to the world we are part of,

Gradients (unfoldings) of infinite space. The rocks on the quarry wall.

How this other world takes place in us, and why we fear it,

Is Cézanne’s subject.

This has the character of an argument – almost a philosophical argument – about picturing in general and the kind of seeing it elicits. The poem thus far is prosy, I hope: there is something about the restraint and straightforwardness of the Cézanne that seems to frown on metaphor or apostrophe. But I think the poem becomes less prosy as it goes on. Here are the final two verses:

There is a poem by Ammons in which a blackbird ‘shoots through a vacancy

In the elm tree and bolts over the house’. The poet wants to show the way the vacancy

Is full of the life passed through it. I don’t think the emptiness

Appearing in the screen of leaves in Hillside, like a window carved out of a green arc de triomphe, has anything to do with

A maker, a bird of passage. You sometimes can find yourself wishing for a hawk or a hare

Or a woman at a cottage door in Cézanne, but the next moment you know the rock face

And the windowless farm have to be as remote from our doings

As they are in Cézanne in order to be our representatives, us in the world, us become colours.

Look at the playing card fields and the tallest tree, raising its stubby hands

In prayer or surrender. Look at the air blue as nothing. This is eternity

With just one blemish – a tiny dark oval high on the hill, rearing leftwards and

Toppling into its own shadow, like a tank at the battle of the Somme. I hear

The sound of artillery clattering in the rocks. The green is smoke

From a shell hole.

This either works or it doesn’t. A lot of the poem came out of nowhere: the tank on the hillside, the arc de triomphe, Ammons’s blackbird. I was soon all at sea: looking at Cézanne is like that. But reading over the poem now, I think I have at least a rough idea of what working or not working amounts to (feels like) in a case like this – what a poem about a Cézanne seems to be after. It isn’t an attempt at description, exactly. But, equally, it isn’t interested primarily in the ‘experience’ of the Cézanne; or not in that experience coming to belong to me, the singular viewer, or even taking on for me an overall character. Williams says of the quality of Bruegel’s mind in Haymaking that ‘it was his own … no one/could take that/from him’; but by the time the poem ends the ‘it’ and the ‘that’ have turned into men with scythes, gleaners, horses, magpies – indelibly plural and material. Material and mental: that seems to be the poem’s burden, with neither quality dominant. This is the characteristic of thinking in painting the poem most wants to emulate.

The best I can do to suggest what my Cézanne poem is trying for is to ask the reader to think of it as a performance of the Cézanne – a performance as opposed to an ekphrasis. Ekphrasis, as I understand it, is premised on the belief that language – full and apposite description – can convert a visual representation into a verbal one. A sequence of words substitutes itself for an absent picture, and, if the words are well chosen, the sequence is capable of having the picture’s objects and visual texture – even its visual structure, its tonality – be present on the page. The words tell us what the picture is of. I don’t believe that in the case of pictures of any complexity – certainly Hillside in Provence – any such thing is possible. What the picture is ‘of’ inheres in its materials, its materiality. And what we can hope for from language (which will not in the least draw back from that materiality, suddenly struck dumb) is a set of pointers, an intuition as to where a picture is going, an emphasis, a key signature, a finger on one or two knots in the visual fabric which seem to be holding the fabric together. The shadows on the rock face, the hole in the foliage.

At one level the point is simple. We don’t expect systems of representation to replace one another. They help each other out; they interest themselves in what one system can do that the other can’t, or can do only limpingly; they go on thinking about what it is in the human condition that calls up – calls on – such a diversity of languages. A performance of a painting is no doubt aware that in the end it is nothing but words on a page, and will be judged as such; but judged (at any rate, this is how I respond to Williams on Bruegel) by some new kind of arrest or movement in the words, brought on by a reaching out – an exposure – to what in the world can’t be said. New phrasing, a new tempo, new kinds of rubato. A performance of a painting ought also to signal at every point (though not with Uriah Heep humility) that it’s a rendering of something that is being looked back at, time after time as the performance continues, and being found incomprehensible. That last word is often an understatement. Hillside in Provence comes to seem monstrous, sardonic, an elaborate trap, as you get to know it. Language fights back. And then the next moment these words too seem wrong, overstressed, in the face of a picture so uncomplicatedly full of light – so keen to spell out the clarity of a southern afternoon. It’s just that the metaphor of ‘spelling’ keeps coming apart as you look at the clarity and try to find words for it.

Go back to the idea that a poem about a painting is, at its best, something like a performance. The analogy is worth proposing, at least as counter to the ekphrasis line of thought, but of course it breaks down. Music is (mostly) composed to be performed, pictures are (mostly) not. A musical performance is of the notes on the page, maybe later traditions of rendering and so on. A poetic performance is not of notes at all, but of an existing complete (anti-)text – a performance that has already taken place, and whose sound is inaudible. Nonetheless poems about paintings regularly seem to want the kind of closeness – the obedience, the accuracy, the technicality – of great non-virtuoso interpretations. But interpreting what is the question.

Hence the indirection, often, of poems that take the question most seriously. Williams’s ‘Haymaking’, for instance. Or Robert Browning’s ‘Andrea del Sarto’. Browning’s poem has sometimes been seen by Andrea’s admirers as unfair to his achievement, or even not really concerned with it (because it wants to tell a Victorian sob story, would be the harshest verdict). It is true that specific paintings by Andrea flit in and out of vision in Browning’s monologue, never quite in focus, clouded by the painter’s encroaching sense of failure. But a sense of failure may be what makes an artist great. The shadow of insufficiency will always seem to some of us Andrea’s deepest, most enduring effect. And ‘Andrea del Sarto’ remains by far the best (closest) performance we have of that shading – in the Madonna of the Harpies, say, or the Borghese Holy Family, or the Louvre’s inconsolable Caritas. Sometimes, whatever Baudelaire may say, a fantasy life of the artist is the only way to bring a set of paintings back from the dead.

A fantasy life, or a fantasy voice. It is strange that a past painter’s speech rhythm, if imagined convincingly, can so alter our sense of his painting’s composition and chiaroscuro. Browning is the master of this overhearing, but there are strong modern instances. Denise Riley’s ‘Letters from Palmer’ is one, not least for the way it uses its extracts from the painter’s letters to annihilate the ‘Samuel Palmer’ of art history books. (The ellipses in the lines below are mine.)

If I seem mirthful it is tinsel & spangles on a black ground …

Our earth is honeycombed with cells of fire. We suffer

the Poles to fight themselves out & the Danes & the Circassians

and need not expect pity when our turn comes …

The stove within me rages …

I am walked and scorched to death …

We are first green and then grey and then nothing in this world.

Iend with a poet looking at a single work. The choice is difficult. I shy away from the wonders of John Ashbery’s ‘Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror’, knowing that if I enter its winding ways I shall never come out. And I confine myself to saying of Michael Fried’s thirteen-line poem ‘Delacroix’ – Delacroix is the poem’s speaker, asking forgiveness of the Arab hunter he has conjured into life and death – that it is everything an anti-ekphrasis should be.*

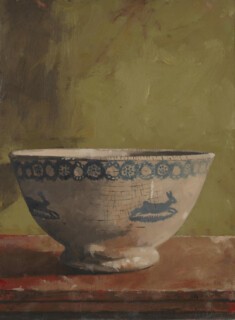

The poem I opt for is longer and less exalted. Its subject is Hare Bowl (2008), a small oil painting by Jeffrey Morgan, owned by Ciaran and Deirdre Carson. Ciaran Carson’s poem about it, which starts in mid-flow, was written in the last months of his life.

His gift revealed itself – a little book-sized still life

of a bowl on a shelf –

Spongeware, 1850s – biscuit fired, says Jeffrey – decorated

with a cut sponge,

A daisy chain of little blue flowers along the rim, and

under them two hares

At full stretch running off to the right on the curve

of the bowl. There’d be

Two others on the other side you can’t see. Like the flowers,

they’re a faded blue, as is

The grass at their feet. Or is it shadow … When we think

of the painted hares

We think of the hares that have entered our lives,

however fleetingly.

Deciding how much to extract from ‘Hare Bowl’ is immediately a problem, and points to the poem’s idea of what it is to describe, and whether describing a painting, or an experience of a painting, ought to fight to keep things in focus, or admit to not knowing where its object of study ceases.

The hare on the runway at Aldergrove airport, seen as you

came into land.

The hare that crossed my path on the Milltown road, hedgerow

to hedgerow in

The blink of an eye. The hare that stood and looked at us

on Rathlin for an age.

The hare that you saw in your garden in Antrim, as tall as

the child that you were.

So we go back to when we never knew each other, never

dreaming then that we

Would end up in this here and now.

Are these lines (there are others like them in the rest of the poem) about the painting? Maybe not. But isn’t the very simplicity of still life meant to call up ‘associations’ of this kind and have them adhere to the object? The length and rhythm of the poem’s lines, above all, keep the answers in doubt. Carson is sometimes called a master of the long line – his previous books about Belfast during the Troubles depended on the drawing-out of a nerveless, disbelieving rhythm – but it’s never quite clear in these final poems whether the short interlinear phrases complete a line (a train of thought) or incomplete one. The prosody seems to be enacting attention and association losing their way and then regaining it. Is that the painting’s fault? Has it got something to do with how seeing normally proceeds, and with what mark-making consists in – Jeffrey Morgan’s mark-making – as a materialisation of seeing? Carson decides he wants to see Morgan’s painting in a better light:

So I bring it to

the parlour – facing south,

It gets the sun from dawn to dusk. I rest it on the back of

the old overstuffed sofa

In the bay window. The muted colours suit the faded peachy pink

of the fabric.

It’s a few minutes after noon and the grey drizzle of earlier

is lifting a little.

I raise the Venetian blind. A cool pearlescent light streams in.

There are textures

In the painting I hadn’t seen before. The bowl itself is

resting on

A terracotta-coloured shelf, little flecks of red in it, the left-hand

corner of the edge

Signed ‘J.M.’ in red. Discreet. You have to look for it. Then I want

to talk about the bowl,

But I’m distracted trying to put words to the green of the wall

it’s placed against.

How many shades are mingled there from pear to sage

to olive green? Now

That I look at it, is there a background hint of yellow? Then

I notice the lemon.

The reader will have realised by now, I hope, that it was necessary to quote a great deal of ‘Hare Bowl’ – almost half of it – in order to suggest what Carson’s ‘performing’ of a painting consists in. The long line or, better, the indirection and interlace of lines, is part of it. But just as much, in the poem’s closing pages, the gradual encroachment or adumbration of other painters, and then the outside world. Memories of bombs exploding a few streets away. Easter. The Antrim Road Medical Centre. ‘I’m often there.’

The poem’s question might be rephrased as follows (I know too crudely): ‘What is looking at a painting like Hare Bowl for, in these circumstances?’ That can’t be separated from another: ‘What is looking at a painting, in any circumstances, actually like?’ What’s its rhythm? What’s its raw material? What’s its point? How can it possibly end up being what you do as death draws nearer? The whole poem, as I understand it, with its delays and wanderings – its balancing between observation and being unable to say – is Carson’s answer.

He closes the poem with a dying fall, sitting in the cab with his wife after chemotherapy: ‘And we’re both so looking forward to seeing/Jeffrey Morgan’s Hare Bowl again.’ It could have been bathos, this. It is bathos. After all (isn’t this Carson’s question?), how can looking at someone else’s interpretation of looking at a bowl on a shelf be anything else? ‘Exceptional commonplaceness’, my dictionary says. Not a bad definition – thinking of Herbert on van Goyen, or Williams on Bruegel, or even Stevens’s prose on Tal-Coat – of what painting has to offer at its highest low moments. Carson in the medical centre, seeing a nurse inserting the needle into his arm, thinks of Vermeer’s Lacemaker.

This may be the deepest reason why poets go on writing poems about paintings. ‘Exceptional commonplaceness’ – they know that most of the time their language is averse to, maybe afraid of, any such thing. But why, if Vermeer wasn’t?

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.