The exhibition Inspiring Walt Disney, now in the dark belly of the Wallace Collection (until 16 October), may seem like a clever way to lure enthusiasts for the popular entertainment of their childhood – together with their own children – into a museum, much of which is dedicated to the decorative art created for the wealthy few in 18th-century France. But in fact it shows, delightfully and ingeniously, the way the rococo, much loved by the great American artistic entrepreneur, shaped the bedrooms of Cinderella’s sisters and the ballroom where Beauty dances with the Beast, and populated the dreams of the public who were enchanted by these films. Specific objects in the Wallace Collection are even shown to have been studied by Disney’s studio artists working in London.

All this is interesting and surprising enough, but the exhibition makes a bolder claim in its cunning subtitle, ‘The Animation of French Decorative Arts’. Title and subtitle are also employed for the book on this subject by Wolf Burchard, who proposed such an exhibition to the Wallace and first recognised that the playful fantasy of popular cinema could make one think afresh about ornamental metamorphosis. After we leave the exhibition the porcelain vessels in the vitrines cease to be the garniture of the idle rich of a distant age and become once more le goût moderne, daring experiments in novel shades of pink and turquoise, bizarre in their confusion of animal and vegetable forms. A wild boar bursts from the flaming ormolu scrolls of an andiron, and within the ornament of commodes and clocks we discover bearded faces leering and chuckling. We understand much better why these objects were so loved – and also, sometimes, hated.

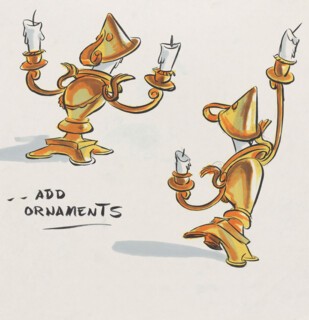

Longcase clocks can of course be ‘grandfathers’, but the clock on a pedestal made in the 1720s by André-Charles Boulle is a major-domo – it provided the inspiration for Cogsworth, the Beast’s servant in his livery of gold and black (and, in passing, we learn from the label that Boulle’s combinations of ebony, turtle shell, brass and ormolu tried to emulate the ‘black and gold aesthetic’ of Asian lacquer). Many teapots pose and gesture like Mrs Pott but the curators propose, in addition, that the enduring appeal of a Sèvres milk jug ‘with its short stubby legs and portly belly’ owes much to its anthropomorphic character.

The exhibition introduces us to many talented artists not so much forgotten as never well known – Bianca Majolie, Hans Bacher, Lisa Keene, Jean Gilmore and others – and to the highly complex and technically innovative procedures behind the production of animated cartoons which are here likened, not inappropriately, to the ceramic and furniture workshops of the 18th century. Hand-drawn preparatory studies are emphasised at the expense of the finished product, which is shown only in short clips and always seems cruder in colour, more saccharine in sentiment and cuter in character than the ‘concept art’ and the rough animation tests.

One of these tests is startling: Glen Keane’s pencil sequence for the transformation of the Beast – which, the label notes, owes something to Michelangelo and Rodin – also depends, for its transitions, on gestural abstraction, and in its fast-changing viewpoints, daring foreshortening and drastic cropping we may glimpse something very like Picasso’s Minotaur. We may regret that Picasso did not make such movies. He came close to doing so in the film he had made of his drawing with light, when he recorded the evolution of some of his major paintings, and in his sequences of thematically related etchings and drawings. Why indeed have we waited so long for William Kentridge? The answer must be that Disney was popular entertainment, to which avant-garde art was by definition averse.

The figurative art associated with the rococo was often enough neither elevated nor edifying – there is the nonsense of chinoiserie and singerie and there are many infants cuddling puppies or blowing bubbles. But there are also the lovers delicately painted by Watteau in wistful or tender attitudes. Their elegance is sometimes emulated by the actors modelled for porcelain by Bustelli and by the miniature ormolu figures such as those that can be found in the Wallace Collection perched on a barometer by Boulle. You will seldom find similar heights of lyrical art in the successive revivals of the rococo, but its absence does not adequately explain the hostile critical reception received by the mutations of this ‘decorative disease’ (as rococo is defined in at least one pocket dictionary). The fastest growing form of art history today explores the history of taste, and an excellent survey of the dealers who created what is rather awkwardly entitled the ‘Anglo-Gallic interior’ has recently been published.* It is alert to the curious political paradoxes associated with the collecting and imitation of the art of the Ancien Régime and the revival of its decor. The rococo had perhaps stronger sexual than political associations: Balzac’s Cousine Bette of 1846 records the use of the ‘Pompadour style’ by the eminent decorator Grindot for the love nest of the repellent bourgeois Crevel and the mercenary and promiscuous Madame Marneffe.

But it could also be merely feminine. In Thackeray’s The Newcomes, published a decade after Cousine Bette, it is not an expensive architect but an ‘Oxford Street upholsterer’ who is responsible for the interior of Mrs Clive’s new house in Tyburnia: ‘Roses and Cupids quivered on the ceilings, up to which golden arabesques crawled from the walls.’ There were ‘countless looking glasses’ and you ‘trod on velvet’. And then, ‘What delightful crooked legs the chairs had! What corner cupboards there were filled with Dresden gimcracks, which it was a part of this little woman’s business in life to purchase! What étagères and bonbonnières, and chiffonnières!’ Whether associated with the most expensive forms of prostitution or with extravagant feminine folly, whether recognised as exquisite in its way (as with Balzac) or hopelessly trifling and vulgar (as with Thackeray), the style was especially vulnerable to disapproval.

The studio artists both during and after Disney’s lifetime loved the idea of crawling arabesques and revelled in endless reflections and in velvet underfoot. Walt himself collected gimcracks. It is a feminine world but with no trace of Madame Marneffe – or indeed of Madame de Pompadour. The exhibition includes Fragonard’s The Swing (c.1767-68), newly cleaned, a joyful hymn to adultery, exhibitionism and foot fetishism, in which the very foliage aspires to the condition of lingerie. Thanks to this exhibition we are able to explore the way Disney artists responded to this painting, making it seem like innocent fun. On occasion, though, something like the lighter products of Surrealism – the lobster telephone and the Mae West sofa – emerges in Disney’s world, unlikely though it is to be noticed by doctrinaire students of modernism, solemnly peering into Duchamp’s urinal or pondering the laborious wit of Magritte.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.