In 1360, Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch to us) wrote a letter expressing his puzzlement at a great change that had taken place during his lifetime. In his boyhood, he said, the English ‘were taken to be the meekest of the barbarians … inferior [even] to the wretched Scots’. Now, in his late middle age, ‘they are a fiercely bellicose nation [who] have overturned the ancient military glory of the French by victories so numerous’ that they had flattened the kingdom of France. What had happened to make the English such an effective force in the decades since their humiliating defeat at Bannockburn in 1314?

The short answer is the Battle of Crécy in 1346. The slightly longer answer would include the English victory at Neville’s Cross the same year, which ended with King David II of Scotland a prisoner in the Tower, to be joined ten years later, after Poitiers, by King John II of France. Some might argue – and professional historians no doubt prefer multi-factored answers – that the tide turned even earlier, in 1332, at the now forgotten Battle of Dupplin Moor, where an unofficial army of dissident Scots and dispossessed English lords not only defeated a much larger and highly confident Scottish army, but also reversed the decision of Bannockburn.

The Dupplin Moor thesis even pinpoints the exact moment of reversal: it came when the Earl of Stafford, seeing his central battle line pushed back uphill by the Scottish phalanxes, shouted to his men (presumably in English rather than the Latin of the Chronicler of Lanercost): ‘Vos Angli vertatis contra lanceas vestros humeros et non pectus’ (‘You English, turn your shoulders to the spears, not your chests’). In other words, ‘stop fighting, put your heads down and shove.’ The English did what they were told and held their line; the Scots found themselves increasingly squeezed by their own men trying to get away from the English archers shooting from the flanks, and by their own reserves piling in from behind, so that more men were crushed or smothered than killed by the enemy. Stafford then launched his tiny cavalry reserve, forty German mercenaries on armoured horses. The English opened lanes for them – this must have taken either a high degree of drilling or loud-voiced subordinate officers – and the Scottish line, already at full stretch, broke, to be cut up in flight with great slaughter by the Germans, and by the unarmoured English archers streaming downhill to join in.

Stafford must have reported back to Edward III, perhaps stressing the need in future for a strengthened central block. The English armies now had a plan and a weapons system: archers thrown forward on both sides to create a killing zone; dismounted heavy infantry as a front line to fix the enemy in place; horses held in reserve. It worked every time, starting only a year after Dupplin Moor at the Battle of Halidon Hill near Berwick – every time, at least, that the enemy could be lured into attacking a prepared position. Which is just what happened, so we’ve always been told, to the French at Crécy.

In his new book, Michael Livingston argues that we have got nearly everything about Crécy wrong. The standard story has been told many times by historians and by novelists, including by Bernard Cornwell twenty years ago in Harlequin. (Cornwell has written a generous foreword to Livingston’s book, saying that if only he had been able to read it before starting his own book, he’d have gone about it differently.) What Livingston calls the vulgato or widely accepted version begins early in the Hundred Years’ War. The English army landed at Cotentin on 12 July 1346 and spent six weeks making its way through northern France to within a few miles of Paris, when much needed reinforcements from Flanders failed to arrive. Outnumbered by the French army, the English took a defensive position on a hill near Crécy-en-Ponthieu, and prepared their winning formation. The battle account contains many scenes we all know: the English longbowmen outshooting the Genoese crossbows; the proud French cavaliers contemptuously overriding their fleeing Genoese allies; Edward III refusing to reinforce his son, the Black Prince, saying ‘Let him win his spurs’; the gallant death of the old, blind king of Bohemia; the Black Prince’s respectful and chivalrous adoption of the old king’s badge and Ich dien motto. Most of all, perhaps, the timid leadership of Philippe VI when compared to that of Edward III, so like his grandfather and so unlike his father, who had failed pitifully at Bannockburn.

Behind this account, one suspects, is the recurrent urge in Anglo-American military historiography to make history more democratic. It’s archers that win battles, not knights. Plumes and shining armour are just for show. You can’t expect much sense from hereditary monarchies, especially French ones. Of course, Philippe and his cavaliers were fools. As for a weapons system, that just means weapons. Doesn’t it?

Livingston disagrees. He points to two underexamined sources: a poem written in 1346 by Colins de Beaumont, though not published until nearly five centuries later; and a ledger kept by one of Edward’s household clerks, William Retford, which lists the king’s kitchen receipts. Who now troubles to read old poems (fanciful) or lists of receipts (boring)? But fanciful or not, Colins was there, as a herald, and his job was to identify the French dead; and Retford, in his quartermasterly way, always knew exactly where Edward was.

Livingston rejects the idea that Edward knew what he was doing, and Philippe didn’t. It’s far too easy, with historical hindsight, to describe something that turned out badly as pure stupidity. But though decisions may transpire to have been incorrect, ‘in the moment they must have seemed correct’ – and that applies to both kings. Edward was not following a plan: he was running for his life, quite sensibly, being outnumbered and out of food, and Philippe was catching him, because (this is one of Livingston’s maxims) he knew how to ‘follow the roads’. Shifting a medieval army, with its wagons and its pack animals and its herds of livestock, was a logistical nightmare, and knowledge of the few available roads was key.

Livingston’s second departure from the historical record has to do with the site of the battle. It’s not where the modern memorials are – and where, unlike the hundreds of arrowheads found on the field of Towton, no battle debris has been recovered – but more than three miles to the south. The French army wasn’t advancing on Edward from the east; it had overtaken him on his chosen road out, and was coming down from the north. (Now we have an alternative site for the battle, battlefield archaeology, with metal detectors, may confirm the result.)

Wherever it was that the English army found itself, the English response was to follow the Dupplin Moor tactic. The Earl of Stafford was himself at Crécy, though Livingston, or perhaps his printers, misidentifies him as the earl of Stanford. (The town of Stafford, in the north-west Midlands, appears to be terra incognita for southern historians.) And he was soon very much in royal favour: two years later he became one of the first members of the Order of the Garter. The Hundred Years’ War made him immensely rich from ransoms, and it seems likely that either he or his son is also the patron for whom Sir Gawain and the Green Knight was written, in its distinctive North Staffordshire dialect.

The Stafford plan was given a vital tweak at Crécy. As at Dupplin Moor, a battle line of dismounted knights and squires and men-at-arms, all in heavy armour, formed a central block, with the specialised archers out on the flanks to shoot the enemy’s horses and create the killing zone. But again as shown at Dupplin Moor, if your armoured block isn’t strong enough – and at Crécy the English were outnumbered two to one overall and much more in the vital armoured contingent – then your position is sure to collapse, leaving your archers helpless. A weapons system is only as strong as its weakest component.

Perhaps in response to Stafford’s advice, Edward built a hasty wagenburg, a barricade of carts tipped over on their sides, to shorten his central front to about a thousand feet, and strengthen it to something like eight ranks deep. This was the first of the king’s three divisions, and it was where the Black Prince ‘won his spurs’ (if he did). There seems at any rate to be no doubt about the wagenburg, though Livingston writes that historians have been reluctant to accept that Edward put himself inside one, possibly ‘worried that [it] makes the English king seem weak’.

In the vulgato account, Philippe’s mercenary Genoese crossbowmen were sent forward as a vanguard, before being outshot by the English longbows, falling back in panic and finding themselves overrun by the charge of their French employers. It’s all very satisfying to English amour propre, with the English yeomanry (perhaps Robin Hood was there) showing their superiority, and the dastardly and deeply undemocratic French cavaliers revealing their contempt for mere foot soldiers, even on their own side.

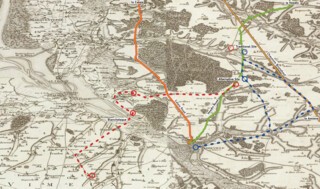

This is probably nothing more than a piece of post-battle scapegoating and one that started very early. (Philippe seems to have executed many Genoese after the battle, in sheer bad temper.) More pertinent is the question of how foot soldiers such as the Genoese got ahead of Philippe’s pursuing columns, when they should have been following behind. Livingston pays close attention to the relevant maps (César-François Cassini’s map of 1757 is reproduced with helpful overlays). Philippe was not only chasing, but trying to get ahead of Edward. The English had forded the Somme at Blanchetaque, where Edward had stopped only two nights before (as indicated by Retford’s invaluable kitchen receipts), had crossed the good road running north-west towards Calais and taken a cross-country track to the Hesdin road running north-east round the edge of the Forest of Crécy. Philippe, in hot pursuit from Abbeville, led his men in a loop east and then north, hoping to get to the Hesdin road before Edward arrived.

He did, and so did his vanguard. But, Livingston argues, the Genoese foot soldiers, trailing behind, were ordered to meet the Hesdin road a little further south. When they arrived on the road, at last ahead of the English, it was the Genoese who were now at the front of this second column, coming up on the flank of Philippe’s vanguard. They may have seen what looked like just a line of carts and decided to attack of their own accord, but Livingston thinks it was probably Philippe, ‘trying to create a plan on the fly’, who threw them forward, to soften up the English defence before his mounted knights charged. The Genoese found themselves, with no prior reconnaissance of the ground, in a muddy hollow, now the Jardin de Genève (or ‘des Genevois’?). There they were outshot, and fell back in confusion into a charge already launched. It wasn’t Genoese cowardice, in other words, nor French callousness. It was something worse: loss of control.

At this point, again in Livingston’s reconstruction, the English made their own mistake. Very likely at the command of the Black Prince, who was only sixteen and saw his charging enemies going down in heaps before him under the English arrow storm, the division of armoured infantry blocking the entrance to the wagenburg advanced out of their thousand-foot gap, banners displayed. The French knights came on again and the Black Prince got a chance to win his spurs – but he very nearly lost the battle, and the war. Several non-English sources say that in the mêlée the prince was in fact captured, and his banner taken, either by the count of Flanders (three sources), the count of Blois (Colins the herald) or the count of Alençon, Philippe’s brother (one source, with a story too detailed to be plausible). If he hadn’t been rescued by a counter-attack led by Edward himself, then the king would have had to sue for peace or lose his son.

As for the gallant King John of Bohemia, led into battle chained to his men so that, though blind, he could strike at least once, the sad story there comes from the forensic examination of his body in its tomb in Luxembourg carried out in 1993. He was wounded in heel and elbow, stabbed in the back, finished off by a dagger thrust through his visor and into his brain, and had three deep postmortem cuts across the wrist, ‘probably an effort to steal his sword or the rings from his hand’. The three feathers and the Ich dien are a myth too: they were not his heraldry at all.

The battle rolled on, and the French rallied as reinforcements came up in the night, many of them led by King John’s son Charles, ‘King of the Romans’, the fourth of the ‘five kings’ of Livingston’s subtitle. Some reports say that the French lost more men on the second day of battle than they did on the first, but it was no longer a contest. The main task remaining was to identify the noble dead, which can’t have been easy. Edward himself gave a list of 21 important casualties, but about half of the men he mentioned had in fact survived, including the fifth king, Jaume III of Mallorca. Colins the herald, with his knowledge of badges and banners, must have been invaluable here, but of the thousands of dead on the field – the English are said in an early report to have collected 1500 pairs of knightly golden spurs, no accurate count being made of lower ranks – Colins identified only 33.

So much for the vulgato version of the battle. But does it really matter, so many centuries later? As Livingston says, ‘the military outcome of a battle is often relatively unimportant.’ If the Crécy campaign was about anything, it was about Edward pressing his legalistic claim to be king of France as well as king of England. The battle did nothing to support that: indeed, it made him less acceptable to the French lords than before. The great gain to follow the battle was the city of Calais, taken after a siege lasting almost a year without serious challenge from the defeated French king. This was a big boost for English trade and the battered English economy, if something of a side effect.

More important, surely, was what Petrarch noted fourteen years after the battle: the sudden rise in the military reputation of England across Europe, and with it an equally steep rise in English self-confidence, which lasted for centuries, reinforced by replays at Poitiers, Verneuil and Agincourt. It wasn’t much shaken by Jeanne d’Arc and has perhaps not entirely faded even now. To quote Shakespeare, ‘Come the three corners of the world in arms,/And we shall shock them.’ The claim has not always been true, but it has been frequently believed. And Crécy, whether in the vulgato version or now with a more nuanced and comprehensive one, was the completely unexpected foundation of the myth.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.