Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill was the first private house to be built in the Gothic style. It began modestly in 1747 as a suburban riverside villa near Twickenham, leased to a Mrs Chenevix who ran a novelty shop at Charing Cross. Gradually it was transformed into what Walpole, wilfully misquoting Pope, referred to as a Gothic Vatican. The house acquired a Green Closet, an armoury, a Holbein Chamber and the Tribune, a jewel-like space, top-lit through stained glass, with ‘the air of a Catholic Chapel’. Walpole described the effect he was aiming for as ‘gloomth’. If the house was strange, the contents were equally startling. Walpole was an avid collector, swimming against the tide. At a time when gentlemen were expected to acquire classical marbles, he was able to pick up later curiosities at relatively small cost. He bought miniatures by Hilliard and Holbein, a cravat carved from limewood by Grinling Gibbons, which he sometimes wore to answer the door, and a clock that Henry VIII had given to Anne Boleyn. His house was open to visitors if they applied for tickets and Walpole would show them round himself. What it all meant, however, was less easy to see. ‘Horrie’ was described by one of his many detractors as a man who wore ‘mask within mask’ and whose character was a series of Chinese boxes with nothing at their centre. He deflected questions by pretending it was all a game. His castle was, he liked to say, a jeu d’esprit, a toy from Mrs Chenevix’s shop, a house of paper. This last was partially true as the battlements were made of papier-mâché and had to be changed after heavy rain.

Walpole was fascinated by contrasts of scale. It was, he claimed, a dream in which he saw a giant hand in armour on the banister rail of a great staircase that inspired him to write The Castle of Otranto (1764), the first Gothic novel. There is a pleasing sense of continuing this game of paper and worlds within worlds in the exhibition of toy theatres Cardboard Gothic: Damsels, Demons and Heroes (at Strawberry Hill until 14 September). Fourteen miniature stages, complete with characters and scenery, have been placed throughout the house, with torches available to illuminate the scenes from different angles. They are all later than Walpole’s time. No doubt there were always enterprising families who made model theatres at home, but as a commercial product they first appeared in 1811, after which they rapidly acquired a standard form.

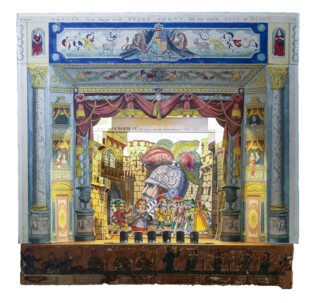

The theatre itself, like its full-size equivalent, had proscenium doors and galleries. The base was wood, the interior paper, and it came with scenery and sheets of characters to paste onto cardboard and cut out. These were available in two versions, priced at ‘a penny plain and twopence coloured’. The phrase entered the language and persisted even when Skelt’s, the biggest manufacturers, halved the price. It’s the title of Robert Louis Stevenson’s essay in Memories and Portraits, in which he recalls his generation’s passion for toy theatres; the wait to save up for a new play and the agony of choosing just one from the stationer’s shop in Leith, ‘which was dark and smelled of Bibles’, and where a beady-eyed salesman kept close watch on a browsing boy torn between these ‘budgets of romance’. For Stevenson, it was the assembling and colouring rather than putting on the play that was the best part and he was baffled by any child who, ‘wilfully forgoing pleasure, stoops to “twopence coloured”’. He was writing in 1887 and contemporaries would have shared his nostalgia: by then the toy theatre had passed its heyday, the half-century or so during which it closely shadowed the London stage.

Toy theatres reproduced specific productions, but the early ones required considerable imagination on the part of the purchaser. They offered an unadapted play text, a selection of scenes and some, but not all, of the characters. By the 1820s, the manufacturers had got into their stride. Costumes, scenery and sometimes individual actors were all represented and the orchestra came as a single strip pasted along the front. The repertoire of the late Georgian theatre favoured the relatively new form of melodrama, a combination of singing, dancing, mime and acting in whatever proportions suited the available talent, so long as they didn’t breach the regulations forbidding spoken drama in any but the patent theatres, Drury Lane and Covent Garden.

This exhibition concentrates on productions with Gothic themes, characterised by ‘gloom, madness, despair and death’ and played out between ‘convents, castles and dungeons’, on the one hand, and ‘forests, cottages and caverns’ on the other. The 1811 Lyceum production of One O’Clock; or The Knight and the Wood Demon, by M.G. ‘Monk’ Lewis, as reproduced in toy form, meets most of the criteria. Lewis got his soubriquet from his novel The Monk of 1796. One of the more notable successors to Walpole’s Otranto, it attracted charges of blasphemy and immorality, which boosted sales but made it difficult to dramatise in any but drastically censored form. One O’Clock was considered suitable, however, despite the fact that the plot centres on child sacrifice and devil worship, perhaps because of the happy dénouement. The intended victim, Leolyn, is rescued with the supernatural assistance of the house’s ancestral portraits, which come to life and direct the heroine to the secret passage along which he has been abducted. The haunted picture became a cliché of Gothic fiction and the scene on show is set in a lofty hall with crocketed niches and heraldic displays of armour much like Walpole’s own, across which our heroine, skirts and headdress flying, pursues the villain, who clutches a wriggling Leolyn under one arm.

One of the attractions of melodrama, in both miniature and full-size versions, was the opportunity it offered for special effects. Weber’s opera Der Freischütz was an instant success when it came to England in 1824 and was adapted in many versions for different theatres. The grand finale was the Wolf’s Glen scene, in which the hero fires the seventh magic bullet and literally all Hell breaks loose. The playbill for a production at the English Opera House makes no mention of the music, which must have been inaudible, promising instead a ‘Storm and Hurricane’ during which ‘the Daemon of the Hartz Mountains appears, the Rattle of Wheels and the Tramp of Horses are Heard.’ The mounting cacophony culminates in a meteorite shower and a ‘tremendous explosion’. Domestic productions, one of which is on show in Walpole’s Bedroom, were expected to reproduce these effects. ‘Blue fire’ was specified in the stage directions for supernatural scenes, while ‘red fire’ was for more realistic dramas including the finale of the most popular of all the toy theatre plays, The Miller and His Men. This ends with the defeat of the brigands after which the mill explodes.

The toy theatres must have caught fire regularly, as did the originals on which they were modelled. Covent Garden burned down in 1808; the following year so did Drury Lane – even though it had been rebuilt in 1794 to incorporate the first ever iron safety curtain. Both were replaced by much larger auditoriums, which had consequences for the repertoire. Covent Garden now had a capacity of 2800, excluding the boxes, and a stage that was eighty feet wide. Filling it was difficult and the subtle character acting of the Kemble generation was no longer commercially or artistically viable. Thus the great age of pantomime was born. The children who would become the Victorians – Disraeli, Pugin and Victoria herself among them – grew up stage-struck. Dickens never forgot these ‘stupendous’ performances ‘when clowns are shot from loaded mortars into the great chandelier’ and ‘harlequins, covered all over with scales of pure gold, twist and sparkle, like amazing fish.’ These are the memories preserved in the toy theatres made between about 1832 and 1865, and no doubt this helped to boost sales to parents recalling their own early excitements.

Real theatres changed considerably in these years. They adapted to gaslight, the monopoly of the patent theatres was abolished and the stalls ceased to be a riotous mosh pit and were filled instead with some of the most expensive seats. Toy theatres, meanwhile, preserved the conventions of the Georgian stage, which were not so far from those of Shakespeare’s day. Shakespearean drama, however, felt the effects of larger auditoriums. The Kembles favoured the Roman plays, in keeping with the neoclassical taste of the time, interspersed with a heavily adapted version of King Lear and Mrs Siddons’s much admired Lady Macbeth. On the new larger stages, selection was made on the basis of scenic opportunities. Henry VIII enjoyed a vogue, as did Colley Cibber’s version of Richard III, famous for the line ‘Off with his head, so much for Buckingham!’ A toy version from the early 1830s shows a favourite scene, Richard’s dream the night before Bosworth, when the ghosts of his victims appear – in this instance gazing reproachfully down from a gilded cloud suspended from the flies.

The oldest theatre in the exhibition dates from some time in the 1820s or 1830s and is known as the Mudge Theatre, after the family who owned it. The Mudges probably lived in North London, but all that is known of them is what can be deduced from the scraps of cardboard on which they mounted the characters, chiefly playing cards and invitations, and the fact that they were obviously very fond of their theatre. They supplemented shop-bought scenery with their own designs, handpainted and tinselled here and there. Clearly of the penny plain persuasion, they were no doubt dab hands at blue and red fire. Their taste in drama tended towards the exotic. The scene on show is an interior which featured in both Aladdin and The Forty Thieves. Another favourite from the pantomime repertoire, Blue Beard; or Female Curiosity, displayed in Walpole’s Blue Breakfast Room, was presented in a combination of Gothic and pseudo-Oriental settings. We are shown the climax, the discovery of the Skeleton Chamber and Blue Beard’s murdered wives. It presents a crowded scene over which a giant skeleton looms, while Fatima, the latest wife, is rescued by her intrepid sister, Irene.

By the time the toy theatres reached their apogee, Walpole’s reputation was at rock bottom. He and all he represented seemed ridiculous, ‘a bundle of inconsistent whims and affectations’ according to Lord Macaulay. No longer daring, merely trashy with a disturbing sense of something sexual and transgressive, Strawberry Hill embodied everything the Victorians despised about their Georgian grandparents. The contents, many of which are now in museums around the world, were sold off in 1842, when they were described by the Times as ‘gewgaws’ and ‘trumpery trifles’. The Castle of Otranto retained some popularity, but it is not surprising that the curators of Cardboard Gothic could find no toy version of a full staging. They have, however, included a satire on it from a pantomime by the Covent Garden house writer James Robinson Planché from 1840. Harlequin and the Giant Helmet; or, The Castle of Otranto is the centrepiece of the display in Walpole’s Library. It plays the same game as the book but in reverse, flipping the horror of the giant armour into comedy by giving the characters enormous papier-mâché heads.

After 1860, few new plays were added to the cardboard repertoire and the number of publishers declined. The last of them, Benjamin Pollock of Hoxton Street, died in 1937 and his daughters later sold their stock, which came, via a series of fittingly dramatic reversals of fortune, to form the core of Pollock’s Toy Museum, which survives in Scala Street in London. The 1960s and 1970s saw a revival of toy theatres. I had one as child, as did several friends. We loved them but we had no option of penny plain and were obliged to stoop to twopence coloured.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.