To advertise simultaneous exhibitions of their paintings at two London galleries in 1939, Maeve Gilmore and Mervyn Peake posed for a photograph at their home in Maida Vale. Peake, wearing a flamboyant floral tie, sits in the foreground, his looming shadow on the wall behind him. He is drawing a charcoal portrait of Gilmore, who stands silhouetted against the window, paintbrush in hand, absorbed in her work. The easel is turned away from the camera, so it’s impossible to tell whether she’s painting a picture of her husband or something else entirely. In her memoir, A World Away (1970), an account of their life together from which she is remarkably absent, Gilmore describes the thrill of meeting Peake on her first day at the Westminster School of Art. He was the teacher, she the student, a dynamic that mapped easily onto married life.

Gilmore always put Peake’s career first. After he died, in 1968, she worked to conserve his legacy, completing the final volume of his Gormenghast series from skeleton notes, organising his letters and papers, and co-operating with various biographers, academics and curators. She had brought up their young children while Peake, increasingly afflicted by mental illness, was on military service, and describes in A World Away the pleasures of their ramshackle life in various London studio flats and houses in Kent, Surrey and Sark as well as the enormous success that followed his first novel, Titus Groan (1946). References to her own work flicker almost imperceptibly: painting is what she does while baby Clare sleeps, while Peake writes, while her sons Sebastian and Fabian play, when there’s no dinner to be made or household accounts to add up. ‘I always seem to have been able to paint when there is intense life surrounding me,’ she writes, ‘despite the eternal meals, the fights of one’s children, and the constant demands of domesticity.’

I have known Gilmore’s art for some years through an Instagram account set up by Sebastian’s daughter, Christian Peake, to celebrate her grandmother’s work: Christian’s regular posts of Gilmore’s paintings – almost all owned by members of the family – have gained a wide following. In her lifetime, Gilmore’s work was exhibited on only a handful of occasions: with the London Group, in the Leicester Galleries’ annual Artists of Fame and Promise group show, and in two solo shows twenty years apart.

In 2011, a joint exhibition of the couple’s work, drawn from the family collection, was shown at Viktor Wynd Fine Art in East London. A solo show for Gilmore followed three years later at Bruce Haines in Mayfair. The latest exhibition, her first institutional showing, is at Studio Voltaire in Clapham (until 7 August), a former Victorian chapel less than a mile from her birthplace at 49 Acre Lane in Brixton. Twenty paintings are spaced out around the main gallery. Several of the canvases bear traces of the family’s many moves and of haphazard storage: punctured with holes where they were once nailed onto walls, scuffed at the edges, the paint chipped or marked.

The arrangement is flanked by two self-portraits, painted in 1958 and 1972. Gilmore is self-lacerating in both, detailing her wrinkles, the bags under her eyes, her furrowed brow. In the earlier painting she cuts an elegant figure, in diamond earrings and a black sleeveless blouse, raising a piece of charcoal between two fingers like a cigarette. Her hair, worn long and loose, is naturalistic, unlike the angular shapes that make up her neck and visible hand. She looks exhausted – the dark hollows of her eyes set her face somehow adrift from its features – as if she’s stayed up late to paint, and won’t stop until she’s satisfied. In the later work she is more active and more commanding: wearing a striped butcher’s apron, she stares out from behind her easel, taking stock of something beyond the frame.

Most of Gilmore’s work is figurative, her subjects drawn from her domestic life: a woman winding wool, acrobatic young boys (Sebastian and Fabian were nicknamed ‘the blue-eyed thugs’ by Louis MacNeice), pears on a platter, the family cats (who appear in more than half of the paintings here). But there is something else at play, too, something fantastical. In its ominous stillness Sark Interior, painted in 1947, reminds me of Dorothea Tanning’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (1943) but without the figures: moonlight from a window, an empty corridor hedged by a slightly forbidding banister, one wall dominated by a painting of a skeletal tree and a mysterious white tower.

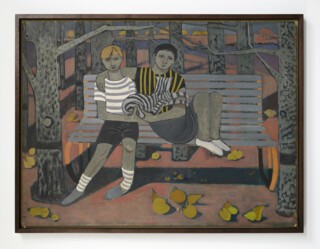

Things are also not quite what they seem in Boys in Orchard (1954), in which the blue-eyed thugs huddle together on a bench, striped shirts and socks criss-crossing the slats of the bench and the striped tortoiseshell cat cradled between them. Trees frame the scene like a stage, while protective branches extend and meet overhead. Part of what is interesting, or unsettling, in Gilmore’s work is her use of contrasts: not only in terms of colour and pattern, but also in her symbolism. The mood of Boys in Orchard is melancholy, but the boys’ expressions are mild. The trees are bare, but there are piles of apples and pears around the boys’ feet. In another painting, two boys play a game of cat’s cradle against an almost totally abstracted background (Gilmore often chose stark single-colour backgrounds to set off her strong outlines). Yet she is excellent on the homely detail: the too-large socks rolled down to the boys’ ankles and the delicate skein wound around their splayed fingers. Her palette echoes the school playground – greys, by turns moody and warm, layered with subtly muted colour – only it’s not at all clear what sort of playground this is.

Her paintings of children at play enter their subjects’ imaginative landscapes.The boy wearing a feathered headdress in Boy in Orchard (c.1952) may well in reality be safe at home, but Gilmore shows him alone in a dark forest. The figure pushing back the curtain in Boy in Window (c.1957) wears the same headdress, while a pair of onions sits just inside the frame, their shoots reaching upwards like sustenance for a spirit visitor. In The Attendant (c.1950) – modelled after Piero della Francesca’s The Dream of Constantine – a boy in harlequin costume sits in contemplative mode, more alert than Piero’s young man, but attuned only to his own thoughts. A stuffed bird (one of a job lot of taxidermy Gilmore and Peake acquired from a closing-down sale) perched on the bench points us to the feather stuck through the boy’s hat. It points us to something else, too: Gilmore’s deft transformation of elements of Piero’s painting. His holy spirit becomes her stuffed bird, his pink and yellow royal tent her pink and yellow harlequin hat.

For a small show, the selection at Studio Voltaire is uneven. Some of the works – two wonky portraits of family cats, a neatly executed depiction of a flint wall, a family scene in the Sark garden – fall flat compared to works I’ve seen online, ambivalent domestic tableaux of far greater depth. Several of these omitted works posit motherhood in ambiguous terms. Mother and Child (1978) shows a bare-breasted woman holding a double-headed rose (it casts a spiky shadow) while an infant claws at her robes. Woman in Doorway (1978), one of Gilmore’s more complex compositions, is a frame within a frame. A cat sips from its bowl in the centre of a brightly lit kitchen, while further back, in the shadow of an open door, a woman stands, arms aloft, part way through undressing. Gilmore’s signature sits at the bottom corner of this second scene, on the threshold between the two rooms, insisting on the woman’s separation from the first sphere. Is the home the painter’s prison, or simply the frame that sets off her painting?

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.