Kafka had consumption, which everyone else also had at that time: look at them up on the tops of mountains, men coughing spots in love with women coughing spots, so that you could draw lines between them until the whole world was filled in. It was a comfort to read him in a year when everyone again had the same disease. More specifically her, for in that moment she was everyone. She thought she could work through him, if she could not work through herself; she thought she could use his hands, if she could not use her own. She drew three exclamation marks next to the sentence: ‘I write this very decidedly out of despair over my body and over a future with this body.’

‘So you are Dr Kafka,’ said the doctor who cured people with colours. But Kafka, before the doctor could write ‘blue’ on his pad, set down his hat in a ridiculous place and flew straight into a prepared speech:

My happiness, my abilities, and every possibility of being useful in any way have always been in the literary field. And here I have, to be sure, experienced states (not many) which in my opinion correspond very closely to the clairvoyant states described by you, Herr Doktor, in which I completely dwelt in every idea, but also filled every idea, and in which I not only felt myself at my boundary, but at the boundary of the human in general.

She had a friend who reserved the greatest hatred for Max Brod – he should never have published his papers, the world should have been a closed eye against Kafka, after all he was his friend. No, she couldn’t quite get there. She preferred a world that was stark and staring, that looked unforgivably into the drawer. She and Kafka were practically twins. Like her, he suffered badly from Who Foot Is That, like her he was dying from I Am What I’m Looking At syndrome, yet he was able to go to cabarets – every night it sometimes seemed – and observe the red knees of the girls.

‘So good. A major classic,’ she had told a friend in high school of The Castle, which she hadn’t read. At that point she strongly felt she had read books she had only heard of, for imagine her getting this far in the first place! Plus she just loved castles, they were so good, a major classic. So her friend read it, and on the day that their book reports were due looked at her sideways, and she responded with a sideways look that said: ‘Some people just aren’t ready for it.’ After that they were less good friends, like Kafka and Max Brod after he published his papers.

Why was Kafka possible to read, when everything else looked like the alphabet ejaculated at random on the ground? Kafka ejaculated the alphabet in order. Every so often an article came out in the New Yorker about how he masturbated constantly to the craziest porn – she couldn’t remember exactly what, but maybe etchings, and pictures of bloomers, and puppets freaking out on their strings – so that it was a wonder he had any time left to write.

Or: ‘Clothes brushed against me, once I seized a ribbon that ornamented the back of a girl’s skirt and let her draw it out of my hand as I walked away …’ Maybe the porn was like that.

The Kafka Museum was a low-lying building next to a lake surrounded by shrieking swans. The restaurants that they passed on the way, and that they might go to afterwards if Kafka made them hungry, all advertised the same thing: pork knuckle. But at the last minute, perhaps fearing such a hunger, her husband only allowed her to go into the gift shop, not the museum itself. He hated the lives of authors, of which she was one.

Perhaps for the bug reason, she could only ever picture Kafka lying on his back. Perhaps because of his surviving photos, she had the idea that he medically could not blink. Perhaps feeling her scrutiny long in the future, he wrote: ‘The time which has just gone by and in which I haven’t written a word has been so important for me because I have stopped being ashamed of my body in the swimming pools of Prague, Königssaal and Czernoschitz.’

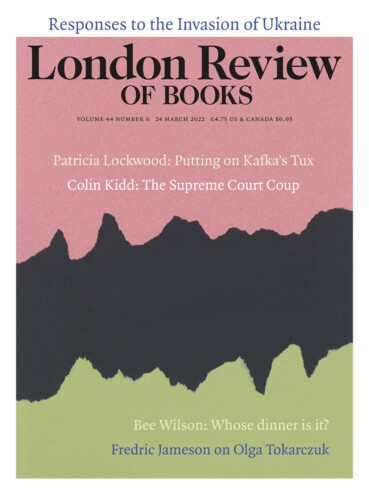

When Kafka tries to buy a tuxedo, everything conspires against him – he must refer to it as ‘the future tuxedo’, eternally receding from him. He wants a tuxedo lined and trimmed with silk, but the tailor has never heard of such a thing. He can only write, in despair: ‘Everything happens to me forever.’ She considered, in a time traveller scenario, taking Kafka with her to Peppe Ramundo, the mobbed-up West Side shop where her husband and brothers rented their tuxedos for her wedding. There was something funny about Peppe Ramundo: one of them only had to say the words ‘Peppe Ramundo’ and the rest collapsed into laughter. Whatever it was, she knew Kafka would be able to find it at Peppe Ramundo Menswear and Black Tie.

The modes, the modes were living creatures and the modes changed – all that stayed the same was that they had four legs and carried our thoughts on their backs. If this were written in the 1990s it would be called ‘Kafka’s Tuxedo’, and in order to illustrate it, we would have resurrected Chagall for a single night so that he could paint Kafka as an empty suit riding a horse over the rooftops of Prague, with a violin between his legs to represent tragedy and two stars for his eyes.

Kafka gave a lecture once, on Yiddish. Beforehand, he experienced ‘a night twisted up in bed, hot and sleepless’, living out his greatest fears one after another: ‘The notices are not published in the papers the way in which they were expected to be, distraction in the office, the stage does not come, not enough tickets are sold, the colour of the tickets upsets me.’

‘Cold and heat alternate in me with the successive words of the sentence, I dream melodic rises and falls, I read sentences of Goethe’s as though my whole body were running down the stresses.’ It was descriptions like these that would later cause us to diagnose Kafka as being schizoid, as having borderline personality disorder, though that was ridiculous, she thought. He had the same thing she had.

When she first started to go mad, she reread ‘The Metamorphosis’ and experienced the pain of the apple core herself, and believed she had an insight about Gregor’s sense of duty: it had nowhere to go, he could have been useful, all the little crawling things of the earth can be useful, even she could be useful, doubled over in pain around her apple core, and for weeks afterwards tried to revise her novel so that it contained the sentence:

give gregor samsa a ball of dung to roll

She read Kafka in a pair of jeans she could not remember buying – it must have been last summer when her body began disappearing. They were Gap, size 4, and she must have gone into the fitting room, the manager must have spelled her name wrong as usual, TRISHA, her heart must have been exploding as it always was then, to think that there were stores in this world full of the fabric, which she had recently begun to feel between her fingertips, the cotton and the canvas of what was, she must have wrestled her way into the jeans she could not remember, which she would wear for – how long? The rest of her life? Surely the tuxedo Kafka was trying to buy was the body, and the lining a permanent caress within it, which the maker had never heard of, which could not be obtained. ‘Trisha,’ the manager must have called, rattling the lock of the door. ‘Are we still doing OK?’

Looking into the face of just such a manager, Kafka had set down the secret of fiction: ‘When I see people of this kind I always think: How did he get into this job, how much does he make, where will he be tomorrow, what awaits him in his old age, where does he live, in what corner does he stretch out his arms before going to sleep, could I do his job, how should I feel about it?’

‘Are you reading that roach again?’ her husband called from the other room, where he had been eating the same apple for an hour, or else Kafka had stretched her perception of time.

Her husband had bought a T-shirt in the gift shop, with a drawing of Kafka’s head on the body of a bug. The sleeves didn’t fit his biceps, so he cut them, and then it shrank in the wash, so he chopped off the midriff. He just kept cutting off bits of it until it appeared that Kafka was strapped to his chest like a baby, and then the two of them would go into the garage and lift weights together. That was his relationship to all literature, and also to all clothing.

To read the diaries of a dead man is to find him aware of everything that is happening to you. ‘It simply goes without saying that the falling of a human hair must matter more to the devil than to God, since the devil really loses that hair and God does not,’ he wrote, directly addressing her little black comb. Underscored three times: ‘Nothing can be accomplished with such a body.’ ‘Then for an hour on the sofa thought about jumping-out-of-the-window,’ Kafka wrote, with dashes – like jack-in-the-pulpit, butter-and-eggs, flowers.

Max’s objection to Dostoevsky, that he allows too many mentally ill persons to enter. Completely wrong. They aren’t ill. Their illness is merely a way to characterise them, and moreover a very delicate and fruitful one. One need only stubbornly keep repeating of a person that he is simple-minded and idiotic, and he will, if he has the Dostoevskian core inside him, be spurred on, as it were, to do his very best.

In his bitterest moments, he spoke of his education and how it had betrayed him. ‘I can prove at any time that my education tried to make another person out of me than the one I became.’ She knew exactly how he felt. They had made her do ‘I’m a little teapot’ in kindergarten and it became true for the rest of her life, that was her handle, that was her spout, she could feel the hot tea coursing through her, whenever she moved it spilled, her life was spelled out somewhere at the bottom of her, in leaves.

Kafka made up a sentence: ‘Little friend, pour forth,’ and ‘incessantly sang it to a special tune’.

His uneducated self sometimes appeared to him in dreams the way a dead bride appears to others. He called it good and beautiful. Possibly it looked like her, pale, 21 years old and knowing nothing of the world, peering timidly into the window of Peppe Ramundo Menswear and Black Tie.

The statue of St John on the stone bridge was the one that all the tourists touched; there was a superstition that it meant you would return to Prague someday. The part of the statue that was touched had become brighter, not like the dull dark rest of the bridge; it was the hand, the knee, it was the foot, she could not quite put her finger on what it was, it was her memory.

A corner was blowing at the edge of her eye: it was the stack of papers she kept weighed down with the cobblestone she had brought back. She had stubbed her toe on it under the astronomical clock – it was dislodged so completely from the smoothness of the street, it threw such an undeniable dark cube in her path, that there was nothing to do but pick it up and smuggle it home through airport security. Amazing that it could now hardly hold down her papers, where previously it had held down the whole of Prague.

If Kafka lived today he would not have to be a bureaucrat, or whatever the hell it was he was. He could be, instead, one of the men in a panda suit she had seen in the old town square, soliciting international coins from children. The idea of the panda, like the idea of the man, was that it stood totally still while the rest of the world poured around it, that it did not move at all and then suddenly extended a hand.

‘I want to change my place in the world entirely, which actually means that I want to go to another planet; it would be enough if I could exist alongside myself, it would even be enough if I could consider the spot on which I stand as some other spot.’ Or was that the tuxedo he meant, the one the tailor couldn’t even imagine?

They had seen the old cemetery coming up the hill through the twilight, but had veered away from it at the last minute, for if there was a second thing her husband couldn’t stand, it was the deaths of writers. Still, it had seemed from that glimpse to be full of tiny houses, each with a name on the door. You could imagine their shadows still living in them, coming back from the markets with their arms full of the shapes of apples, fish and almonds – just as letters sometimes seemed on the page, cast by something living and larger. ‘I find the letter K offensive, almost disgusting, and yet I use it; it must be very characteristic of me.’

So the best resource is to meet everything as calmly as possible, to make yourself an inert mass, and, if you feel that you are carried away, not to let yourself be lured into taking a single unnecessary step, to stare at others with the eyes of an animal, to feel no compunction, to yield to the non-conscious that you believe far away while it is precisely what is burning you, with your own hand to throttle down whatever ghostly life remains in you, that is, to enlarge the final peace of the graveyard and let nothing survive save that. A characteristic movement in such a condition is to run your little finger along your eyebrows.

She examined the blurbs on the back of the book. ‘If anyone ever said, of me, that I had “a mind living in sin with the soul of Abraham”, I would lose my fucking shit,’ she said. ‘I would go crazy.’

He was coming into the public domain this year; that meant all of him, she thought. Imagine the feeling of release, being dead and belonging to the people. Now someone gets to draw a little cartoon of you, or insert you into their Amish romance; now you’re a character at an off-brand waterpark, trying to cover up your body as you go mournfully down the slides. Next year, they will dress freely in his suit in Prague, will extend a hand in him suddenly, as the rest of the world turns.

‘Did you find in the diaries some final proof against me?’

She had thought of the way she wanted the diaries to end, with a sudden parting gift in the palms of her hands – what was it he had written? ‘The work draws to an end the way an unhealed wound might draw together.’ But it snuck up on her gradually, in bare feet and with pale swinging pendulum, the knowledge that Kafka seems to have spent time in a nudists’ colony. For four hundred pages he had written of people who were clothed and then the ribbons swished, the buttons popped, the shapes all fell to the forest floor. ‘When I see these stark-naked people moving slowly past among the trees (though they are usually at a distance), I now and then get light, superficial attacks of nausea. Their running doesn’t make things any better.’ How could he know what she needed, from the moment she read about his unattainable tuxedo, the silk lining, the tailor who could not yet understand the language he spoke, to the moment that he wrote, ‘It is impossible to clean the kind of clothes we wear today!’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.