Songlines, also known as Tjukurpa, Dreaming tracks, creation law, are the sung pathways of First Australian ancestors. These invisible tracks were created by the totems, or ancestral beings, of Aboriginal creation myths as they wandered across the continent naming everything they saw and leaving a trail of words and musical notes in their wake. Songlines chart critical sites and resources, linking stories to landscape: they are both map and compass. They provide practical signposts such as the location of rivers and caves – survival knowledge essential to desert life – but also describe the origins of the universe as well as moral codes and their consequences. For generations, the songs allowed First Australians to re-enact ancestral exploits on the sites where they occurred – not in a place called Australia but ‘Country’, a term that encompasses the spiritual connections of specific peoples to land, water, memory, custom and law, and which links hundreds of ancient languages. As access to these sites has diminished, painting, along with other artforms, has become an important means of preserving the Indigenous knowledge bound up in songlines.

Knowledge of the songs and stories that constitute this collective worldview (known as ‘the Dreaming’) is a birthright – it can’t be acquired or appropriated – and access is restricted according to gender, kinship and place. This means that the artists on show at Songlines, the National Museum of Australia’s exhibition of First Australian art, have story rights only to the sections that traverse their bit of Country. (The exhibition is on display at the Box in Plymouth until 27 February before travelling to Paris and Berlin.) A songline might begin in land belonging to one Indigenous group and move through another and another: there are more than four hundred distinct groups and languages. The many collaborative works in the exhibition therefore required ‘everyone to know what they can and can’t tell … a precise knowledge of how … kinship, Country and story fit together’. The proper communication of knowledge is central to them all, regardless of medium or style. The paintings of Tjapartji Kanytjuri Bates – massive canvases of acrylic, hectic with colour and code – are accompanied by a note that tells us ‘iconographic details [have been left] intentionally elusive, except for those with the seniority to read them.’ This isn’t a gesture of hostility or exclusion, but self-determination. Despite the artists’ desire to create works that travel between cultures, these paintings have not been made for us. The viewer is a guest; any pretence of disclosure or easy understanding would prevent us from experiencing the vertigo of Country.

Whether you start the exhibition in Martu Country, the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands or Ngaanyatjarra (NPY) Lands, the same origin narrative emerges: the malefic pursuit of women. (Gallery staff warn visitors about this ‘controversial’ material.) The Dreaming story of the Seven Sisters, one of the most celebrated songlines, crosses half the continent, from the Central Desert to the West Coast. It describes the Sisters’ attempt to escape Wati Nyiru, a shapeshifting sorcerer. His hunt is relentless, but their flight and their courage become part of the Dreaming: the narrative of the story – every plot twist and close shave, even the women’s ultimate demise – can be traced on the features of the land and the night sky. They become boulders, dig into caves or dive in waterholes, creating sacred sites recognisable to their descendants. When they fling Wati Nyiru into the air and, defeated, fly up to the firmament, they become the star clusters we know as Orion and the Pleiades.

The exhibition’s focus on the Sisters is intended to celebrate Indigenous women’s relationship to Country, their particular forms of knowledge and their endurance. Alison Milyika Carroll’s (APY) rhetorical question occupies an entire wall: ‘Who are a group of women that work together in our culture, that know about their country and the plants and the animals around them and use this knowledge as they travel? The Seven Sisters of course!’ But this isn’t the whole story. In canvas after sculpture, ceramic after weaving, we are confronted with women weakened, poisoned, threatened, spied on, tricked, pursued, killed and beatified. They use their knowledge to survive both an unforgiving land and the violence of their pursuer; they run, they fly, they stand their ground, they fight back, they die. And for what? So that future generations have an ancestral record of female resilience. ‘Dreaming is an active continuous time,’ Kim Mahood writes in one of the catalogue essays, ‘an animating presence in the land, reactivated whenever Country is traversed by its keepers, or song and ceremony performed.’

Most of the artists in the exhibition are elders: women and men who use paint and other materials to maintain their connection to Dreaming when they can no longer travel to the sites to which their songs pertain. A wall devoted to Bates, who died in 2015, tracks the parallel course of her artistic expression and her senescence. The works made towards the end of her life, at Wanarn Aged Care Facility, diminish in size, precision and narrative action; they also drastically change medium. Huge early canvases, teeming with life and abstract symbolism, become modest, irregular, spare. Much of the space is left empty and the once intricate forms become jumbled (compare Tjukurrpa Kungkarrangkalpa, from 1995, with Kungkarrangkalpa, made eighteen years later). Canvases are replaced by sheets of cardboard, pillowcases, table-tops – anything that was to hand. One dog-eared piece of cardboard is marked with fierce orange crosshatches, a far cry from the technical brilliance of rarrk (an Aboriginal technique of crosshatched bark painting) or Bates’s earlier work. A pillowcase displayed nearby, Untitled (2011), swirls with jagged concentric circles, almost tessellating.

The obligation to preserve these stories is not shouldered by elders alone. Technology is now integral to the survival of the songlines. The Martu filmmaker Curtis Taylor writes that ‘just like the old people, we are dreaming. We have a new dream with technology. We’re using the newest technology with the oldest culture.’ One collaborative work, Travelling Kungkarangkalpa, is an audiovisual hemisphere showing the multi-layered rock art at Cave Hill (Walinynga) – footprints, ancestors and animals dashed in bright pigments – as well as the terrestrial movements of the Seven Sisters and a time-lapsed transit of the constellation.

The songlines continue across APY and NPY Lands. Senior lawmen and women, projected on six-foot screens, greet visitors in English and Pitjantjatjara. Tarpaulins have been spread over the gallery floor to map family trees (‘kinship canvases’); bowls carved of red river gum represent the Sisters’ travels; wooden snake sculptures writhe from the walls; mesmeric, pointillist paintings range from the minor to the monumental. There are echoes of Cy Twombly’s linear minimalism, of the kinetic force of Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner. But these works aren’t propelled by the names, movements or techniques of the 20th century, and such associations are ours alone.

The scene-stealers at the show are the anthropomorphic grass figures of the Seven Sisters assembled by the Tjanpi Desert Weavers. In one room they are suspended from the ceiling, forged forces of grass, branch, raffia, fencing wire, feathers and wool. Their forms change from region to region: in Martu Country, the grass figures have legs; elsewhere they have mermaid tails. In APL Lands, the women are trees, shapeshifting to escape their obsessive pursuer. Wati Nyiru creeps along the ground towards them.

An Aboriginal-owned art centre has been re-created in Plymouth ‘in all its raw profusion of colour and clamour’. The room booms: melancholy chanting, birdsong, senior women discussing Dreaming in endangered languages. A battered bench holds paint-smeared brushes, fat bottles of acrylic, splattered cloths. There are painting drawers belonging to the Warakurna Artists (NPY Lands): a plastic trolley of personalised cubby-holes stacked with paint tubes, tea mugs, odds and ends. Indigenous art centres such as that of the Warakurna Artists first emerged in the early 1970s. After the Labor government endorsed community decision-making, the Aboriginal Arts Board began to commission and exhibit Indigenous artworks and the Western Desert arts movement was born. Aboriginal artistry developed alongside the land rights struggle of the 1980s and 1990s, and the centres are now cultural and economic hubs. The works of Dreaming attract interest from private collectors, the international art world, the world of finance. Although the curators are keen to portray this period as one of autonomy and empowerment, others have described its exploitative character: a settler-controlled industry that filched Dreaming stories from artists, altered them to suit global audiences and peddled sacred paintings for profit.

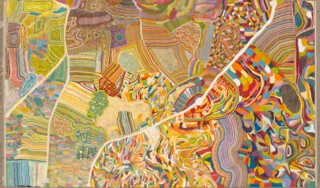

Yarrkalpa (Hunting Ground), a huge linen canvas painted by eight women Martumili Artists, stops you in your tracks. Riven by thick white creek beds, its Technicolor pointillism conveys intimate knowledge through geospatial vision and microscopic detail. The painting comes at the end of the Martu Country rooms and is paired with a video installation, Always Walking Country: Parnngurr Yarrkalpa (2013), directed by Lynette Wallworth. The installation is made up of three screens: on one, smoke billows from scrub to sky, waterholes bubble with life and red ants scuttle backwards and forwards. On another, the Martumili women blur in and out of focus as, slowly, they bring their visual encyclopedia to life. Ecology, creation and Country painted on canvas in a hot tin shed. Visitors to the exhibition point out the bushfires visible in the distance, but don’t acknowledge the extraordinary act we are witnessing, or the extraordinariness of our doing so. The Songlines curators are all First Australians and our encounter with the pieces is unmediated by the usual gallery interface: it was not felt necessary, for instance, to give the songlines legitimacy by invoking the familiar tropes of Greek mythology. First Australian culture is testament to 50,000 years of survival – or as many Indigenous intellectuals refer to it (incorporating a sense of political resistance), ‘survivance’. Songlines reminds us that colonisation is pervasive, but not totalising. Compared with the brief glimpses offered in Tate Modern’s A Year in Art: Australia 1992 (on display until the autumn), Songlines is a triumph, a feat of immersion without condescension or self-abasement, without flattery or false intimacy. This is one of the oldest cosmologies on Earth. The words ‘terra nullius’ are nowhere to be found at the Box.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.