Apotheosis can happen to anyone, although in the case of women it is rare. Men, however, are deified with astonishing frequency and their reactions range from bewildered irritation to dismay. While the idea of being godlike may be attractive, being an actual god is less so. One is at the mercy of one’s worshippers, who tend to be demanding, dictatorial and impossible to shake off. Anna Della Subin’s Accidental Gods is a philosophical and historical exploration of the phenomenon from Jesus Christ to Prince Philip and Narendra Modi, written with a poise and lucidity that allow full play to the comic aspects of her subject, while considering the frequently disastrous consequences.

Haile Selassie is the first and one of the best known of her case studies. The story of Rastafarianism is in many ways typical, not least because the object of its devotion resented it. Its emergence from a tangle of paradoxical paraphernalia is characteristic of many religions, including Christianity. Subin traces the history of Ethiopia as the semi-mystical site of Black liberation across the African diaspora, from its roots in the 18th century to the moment, at Haile Selassie’s coronation in Addis Ababa in 1930, when it appeared to have been realised. As a photographer from the National Geographic Magazine put it, ‘the centuries seemed to have slipped suddenly backward into biblical ritual.’ The fulfilment of this prophecy was recognised by Leonard Percival Howell, a Jamaican preacher. Taking the National Geographic of June 1931 as his text, Howell announced that a white prince (the Duke of Gloucester, who represented George V at the coronation) had bowed before the Black king. ‘We of the black race are now free.’ Haile Selassie was, he said, the Black Messiah. Events unfolded from this point in a way that becomes familiar as Subin’s book goes on.

Howell was imprisoned by the colonial authorities and while detained wrote The Promised Key, the foundational text of the new religion, which throve on persecution and overlooked inconvenient details, not least the National Geographic’s openly racist and imperialist editorial stance. The magazine was warm in its support of Mussolini and the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, which forced Haile Selassie into exile. From an Italianate villa on Kelston Road, Bath, he protested against his deification. He found the use of his earlier given name, Ras Tafari, offensive, and did not consider himself to be Black. Meanwhile Marcus Garvey, who accepted Haile Selassie’s own account of his lineage as a descendant of Solomon and so considered him to be Jewish, discounted him as an ally in the struggle for Black liberation. Despite this, Garvey was taken up by the religion as a divinely inspired prophet, the John the Baptist of Rastafari. By 1940, he too was in England. Haile Selassie declined an invitation to meet him. Garvey died that year, a fact that many of his unwanted followers refused to believe, and since Haile Selassie’s reported demise in 1975 his own followers have awaited his second coming, which they anticipate will occur in New Zealand. The National Geographic article remains an important text. In A Journey to the Roots of Rastafari, published in 2014, Abba Yahudah Berhan Selassie gives a numerological exegesis of the article showing that the numbers in it add up to 360, signifying ‘infinity, completeness and perfection’.

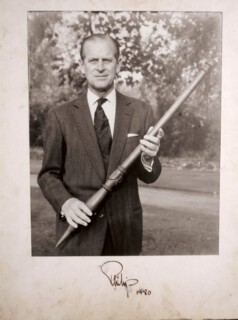

Subin’s is a scholarly, footnoted work and she tells this story straight, allowing it to open up her broader themes: imperialism, the invention of ‘religion’ as a distinct phenomenon separable from culture or politics, the amorphous nature of belief. Deification holds a mirror up to all of these. It was around 1977 that Prince Philip became aware that he was a god. It had happened three years earlier when the Britannia moored off the coast of Aneityum (in what is now Vanuatu). Jack Naiva, one of the chiefs of Tanna, a neighbouring island, rowed out to the royal yacht. As soon as he saw Philip he realised that he was witnessing the fulfilment of a local prophecy: ‘I saw him standing on the deck in his white uniform,’ he recalled. ‘I knew then that he was the true messiah.’ This was all very awkward. The British Empire in a late phase of managed decline had no desire to extend its authority into the supernatural, to add to which Tanna was governed jointly by Britain and France in an uneasy condominium. In the event, Philip, known for what his friends called ‘gaffes’ and other people considered casually racist remarks, handled the situation with delicacy and respect for all concerned. The gift of a nalnal, or traditional pig-killing stick, was reciprocated with a photograph of Philip in a smart suit in the grounds of Buckingham Palace holding the stick in what he had been advised by anthropologists was the correct manner. In 2007 he received a delegation from Tanna at Windsor Castle. But his ‘accidental coup’ was not without the difficulties that accompany deification. The French were furious, accusing the British of exploiting the situation for political ends and pointing out, perhaps with a hint of pique, that ‘the French do not seem to get implicated in similar situations.’ When Vanuatu became independent in 1980, the islanders wrote to Prince Philip to complain that they now had to pay federal taxes. He replied that this was indeed necessary but his letter, on Buckingham Palace headed paper, was regarded as having talismanic properties and was waved in the face of tax collectors as evidence of exemption.

Whatever the real motives of British and French colonialists – Subin is too sweeping in her assertion that ‘profiteering and racism’ were ‘only ever loosely masked by lofty ideals’ – the efforts to Christianise the natives presented a severe challenge to the 19th century’s belief in its own ‘rational religion’, and nowhere more so than in India. Robert Caldwell, a young missionary to Tinnevelly (now Tirunelveli) in Tamil Nadu in the 1830s, was exasperated by the response to his preaching: ‘To every … argument they mutter in reply: “Who has seen heaven? Who has seen hell?”’ Their own religion was better documented and revolved around Pooley Sahib, the spirit of a British officer killed in a surprise attack at the Arambooly Pass in 1809. Caldwell’s parishioners left their god offerings of brandy and cigars, like those found in the officer’s bag, and worshipped him in a combination of local and Christian rituals that were, Caldwell reported, ‘intolerable … mangled members of our own noble confession of faith’.

It was all but impossible to safeguard the ‘noble’ Christianity of the imperialists from local interpretation. In Bombay, a statue of Richard, marquess of Wellesley, was commissioned in 1806 on his retirement as governor-general. It rapidly became an object of devotion. An exasperated onlooker complained that the ‘Maratha simpletons’ imagined the East India Company had ‘kindly imported an English god’ and so began politely leaving offerings and performing pujas before it. But if Wellesley’s statue wasn’t intended as an object for religious worship, what was it? It was symbolic, metaphorical, calculated to induce certain thoughts and reinforce particular ideas. The difference between a statue and an icon might be one of emphasis rather than substance. This was an uncomfortable thought. The British dealt with what they saw as the chaotic nature of Hinduism as they dealt with the rest of the subcontinent, by attempting to impose their own bureaucratic systems. What Hindus needed, according to William Crooke, a magistrate in the North-Western Provinces, was ‘an acknowledged orthodox head … to keep up the standard of deities and saints’.

Of all the hazards of sudden deification, Subin explains, spirit possession is ‘the most physically uncomfortable’. It was most common in Africa and especially under the French in Niger, where in 1925 a group of spirits called the Hauka took possession of the inhabitants of the village of Chikal. The Hauka instructed the villagers to go into the bush, where they set up a parallel society that was a parody of the colonial administration. Holding imitation rifles made of wood, the spirits spoke through the villagers in the voices of soldiers, magistrates and bureaucrats; they marched in formation and vomited black ink, ‘the quotidian liquid’ of the French regime. The district commissioner, Major Crociccia, a Corsican, had the villagers rounded up and imprisoned. He personally beat a woman called Zibo through whom the Hauka had first spoken. ‘You see,’ he told his prisoners, ‘there are no more Hauka. I am stronger than the Hauka.’ By this point in Subin’s book it comes as no surprise to learn that as a result the Hauka were discredited and replaced by Corsai, ‘the Corsican’, who was none other than the deified spirit of Crociccia himself. With the aid of their new god, and much to his astonishment, his followers used their divinely inspired strength to break down the prison and escape.

As the 19th century wore on, people in the northern hemisphere became increasingly aware that what separated the spiritual life of the colonisers from the colonised was not superiority of character or access to a higher truth. In distinguishing between the local religions and their own they were creating a distinction without a difference. But the century had another credo, science, and so the idea of world religions, and specifically the science of religion, was born. Its progenitor, Friedrich Müller, lectured on the subject to an audience that included Queen Victoria. She was so much engaged, Müller reported to his wife, that although she had her workbag with her, she ‘did not knit at all’. Müller’s theory was that religious belief, what William James called the ‘mystical germ’, was common to all humanity throughout time, but its manifestations were distinct. The project of rationalising and categorising these took the form of scholarly editions of the scriptures in the fifty-volume series Sacred Books of the East, edited by Müller and published by the Oxford University Press in 1879. As so often in the sticky matters of belief, the science of religion’s attempt at objectivity was absorbed into its own evidence and it ‘created what it purported to describe’. The theory of distinct religions with authoritative texts existed nowhere outside the academic apparatus of these editions. As applied in the field it was problematic. In India, the Hindu practice of sati, the self-immolation of widows on their husbands’ pyres, was appalling to the British, but there was resistance to interference with religious practices. Müller, like some Hindus, argued that sati wasn’t a true religious obligation, so might be censured. After interventions in different states, Victoria banned it throughout India in 1861. Not long afterwards she became a goddess in Orissa, an event which she seems to have taken in her stride.

It was the scientific reification of religion, taken to its extreme, Subin argues, that led to the catastrophe of partition in 1947. It divided the population of India into Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs as ‘impermeable entities’, quite alien to the experience of Indians themselves, unleashing the ‘violence and chaos’ that cost two million lives.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.