Thomas Hobbes used to tell people that the Spanish Armada was the reason he had been born prematurely. ‘My mother gave birth to twins,’ he said, ‘myself and fear.’ He never shook off the sense of dread. More than half a century later, having fled England for France, he wrote Leviathan, predicated on the view that fear is the chief driver of man. Hobbes would have recognised the England depicted in Clare Jackson’s Devil-Land, a country in danger of ‘popish’ encirclement, beset by disaster, and suffering from rebellion and religious extremism. ‘To contemporaries and foreigners alike,’ she writes, ‘17th-century England was a failed state.’ Far from being the New Israel of the puritan dream, it was, in the eyes of Europe, a place from which God had withdrawn his favour.

Jackson reappraises Stuart England in two distinctive ways. Her narrative starts with one foreign fleet in the English Channel – Philip II’s failed Armada of 1588 – and ends a century later with another: William of Orange’s invasion flotilla, which brought about the ‘Glorious Revolution’. Both 1588 and 1688 were moments of intense insecurity and both were presaged by the spilling of Stuart blood: the shocking execution of Mary, Queen of Scots in 1587 and the debilitating nosebleeds of James II, which prevented him from defending his crown at Salisbury against William, his son-in-law as well as his nephew. The caesura comes on 30 January 1649 with the public execution of Charles I. A Dutch pamphleteer punned that the English (Anglorum) could no longer be seen as angels (angelorum), but as inhabitants of a ‘Devil-land’ of regicides.

Jackson’s other innovation is to examine England’s woes not through the eyes of its people, but from the varying perspectives of a vast cast of foreign ambassadors, envoys and courtiers who tried to make sense of them. There are some limitations to this approach. Ambassadors were supple, frequently hostile witnesses, who reported, distorted and occasionally disrupted events according to shifting alliances and priorities. They didn’t tend to look much beyond the elite world of politics, and so were unlikely to report on the punishment of criminals, the administration of poor relief, the maintenance of watercourses and the many other ways in which England, for most of the century, was nothing like a failed state. Even potential showstoppers like the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 (‘a hyperdiabolical devilishness’) and the Great Fire of London in 1666 were ultimately dealt with effectively.

By the end of the century, as Jackson notes, a resurgent London was Europe’s largest city, with a population of more than half a million. There were signs of vigour, too, in the English acquisition of Jamaica, Mardyke and Dunkirk, won by force in the 1650s, and Bombay and Tangier, given to Charles II when he married Catherine of Braganza in 1662. The Dutch raid on the River Medway on 12 June 1667, which led to the capture of the Royal Navy’s flagship, the Royal Charles, was a humiliation (the carved stern piece is now on display in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum), but it should be set against the destruction of the Dutch flagship off Lowestoft two years earlier and the Treaty of Breda of 31 July 1667, which allowed the English to retain the colony of the New Netherlands (including the port of New York) in exchange for control over the Indonesian island of Run – a good deal, as it turned out. Even during the civil war, when the country was convulsed by violence and experienced unprecedented political upheaval, Parliament was able to pay and supply its troops, set up England’s first permanent military hospitals and extend welfare provision to military widows and orphans. Meanwhile, plenty of other countries might also have been classed as ‘pandemoniums’, to use John Milton’s newly minted word. France endured regicide and rebellion and the Holy Roman Empire lost perhaps five million lives to the Thirty Years’ War. Nothing in England was comparable to the sack of Magdeburg in 1631.

Jackson anticipates and deflects many of these points in her introduction. Devil-Land ‘emphasises confusion, distrust and trepidation, rather than confidence, buoyancy and assurance,’ she writes. Its ‘metaphorical texture’ is not plush tapestry, but ‘the deliberate “openwork” of a 17th-century doily, designed precisely to expose Stuart England’s unstable fissures and vulnerable fragilities’. The result is a richer picture not only of England under the Stuarts and as a republic, but also of its neighbours. Jackson’s chief contention is not so much that England was a failed state, but that the key to understanding many of its problems and divisions lies in Europe. The research is impressive, the writing lucid and every page thought-provoking. It is also tremendously entertaining. Waspish diplomats, then as now, make good copy. One can picture perfectly the hangdog look of Viscount Scudamore, the resident ambassador in Paris in 1635, who was accused of speaking French ‘as if he had learned it in Herefordshire’.

England was certainly an oddity to her friends and enemies on the Continent. ‘There was no school in the world where one could learn how to negotiate with the English,’ the Spanish envoy Íñigo Vélez de Guevara, count of Oñate, told his Venetian counterpart in 1637. The following year, a Jesuit in England groused that he had ‘never been in a country where things go so slowly or stupidly … I seem to be in the middle of Spain.’ At other times, however, affairs moved fast, so fast, in fact, that Pomponne de Bellièvre, the French ambassador in 1646, complained that ‘one no longer reckons time by months and weeks, but by hours and even by minutes.’ The Huguenot Maximilien de Béthune, marquis of Rosny, suspected that the water had something to do with it, the English having ‘contracted all the instability of the element by which they are surrounded’. Others blamed a lack of executive heft. With no standing army and no prerogative tax like the taille in France, English monarchs had to seek funds from a parsimonious Parliament. The Stuarts resented that assembly’s assertiveness. ‘I am a stranger,’ James VI and I confided in the Spanish ambassador in 1614, ‘and found it here when I arrived, so that I am obliged to put up with what I cannot get rid of.’

That James, a Scot, was complaining to a Spaniard about his alien Parliament was a large part of the problem with the Stuarts, at least from the perspective of their southern subjects (and conversely explains some of the appeal of ‘God’s Englishman’, Oliver Cromwell). James was accused of wanting to sacrifice his new kingdom’s distinctiveness for the sake of a ‘Great Britain’ in which the Anglo-Scottish borders would be reconfigured as ‘Middle Shires’, Charles I of being swayed by Spain to an ‘execrable and rotten’ degree, and Charles II of turning England into a ‘tributary’ of France. It is indicative of Parliament’s concern for English liberties that in 1604 a bill was placed before the Commons seeking confirmation of the provisions of Magna Carta. When Guy Fawkes was caught with 36 barrels of gunpowder under the House of Lords the following year, he told his interrogators that he had wanted to blow the lot of them back to Scotland.

Another problem for the Stuarts was that, in spite of their persecution of Catholics, they were associated with ‘popery’. England was a leading Protestant kingdom – God’s chosen nation, according to puritans – and therefore vulnerable throughout this century of Counter-Reformation to the Catholic armies and missionaries who were reclaiming territory at an alarming rate. Between 1590 and 1690, the geographical extent of Protestantism was reduced from one half to one fifth of Europe’s landmass. Englishmen feared the return of human bonfires and, as one tract threatened, of ‘troops of papists ravishing your wives and your daughters, dashing your little children’s brains out against the walls, plundering your houses and cutting your own throats’. For many Protestants in England, the need to keep popery out, by fighting Catholics in Europe and stamping on creeping popery at home, trumped all other considerations.

James II, the last male monarch of the dynasty, was openly Catholic, and his older brother, Charles II, had converted to Rome on his deathbed. James I and Charles I were both devoted to the Church of England, but favoured a ceremonial form of worship which to the hotter sort of Protestant smacked of popery-by-stealth. All four Stuart kings had Catholic queens (Anne of Denmark covertly) and absolutist tendencies, or at least a preference for consulting Parliament as infrequently as possible. Fewer parliaments meant less money, however, which tended to result in arbitrary taxation at home and a degree of suppliance abroad that invited further charges of popery.

Jackson highlights the novelty of Stuart foreign relations after a period of relative isolation. Christian IV of Denmark’s state visit to England in 1606 was the first by a foreign ruler since Henry VIII’s entertainment of the Holy Roman Emperor in 1522. James II’s journey through Ireland in 1689 was the first time an English monarch had visited since Richard II in 1399. The marriage of James’s daughter Elizabeth to Frederick V, the Elector Palatine, in 1613 was the first royal wedding in England since Mary Tudor’s in 1554. It cost James £93,000 and a terminal headache, since the couple’s acceptance of the crown of Bohemia from Protestant rebels in 1619 effectively triggered the Thirty Years’ War. The deposed king-elect, Ferdinand, who was soon afterwards crowned Holy Roman Emperor, sent troops to retake his throne in Prague and seize Frederick’s ancestral lands in the Lower Palatinate. Frederick and Elizabeth were defeated, exiled and ever after mocked as the Winter King and Queen. They appealed to James for help, but he refused them asylum in England and insisted, fruitlessly, on a diplomatic solution. A Jesuit play performed in Antwerp in the early 1620s contained a scene in which supplies promised to Frederick turned out to be 100,000 red herrings from the Danes, 100,000 cheeses from the Dutch and 100,000 English ambassadors.

Charles I had a stab at warrior status after succeeding his father in 1625, but his attempt to seize Cadiz in October 1625 resulted in decapitated English heads being booted down Spanish streets ‘like footballs’. A botched naval expedition in 1627, intended to relieve the besieged French Huguenots at La Rochelle, led Charles to be charged with squandering England’s honour: ‘Poitiers, Cressy, Agincourt: all lie buried.’ Emasculated, Charles reverted to his father’s policy of seeking restitution for Frederick and Elizabeth through diplomatic channels while remaining neutral in the wider European war. After 1629, he had few other options, since, unwilling to address Parliament’s demands for religious and fiscal reform, he had embarked on a Personal Rule that lasted for eleven years and led to civil war.

The conflict that was openly declared in 1642 had its origins in a Protestant rebellion in Scotland in 1639, but was framed by puritans as the result of a popish plot designed to soften up England for the invasion of the Whore of Babylon. Charles’s ministers contemplated using Irish or Spanish troops to fight his Scottish subjects, which hardly alleviated fears. As Jackson writes, ‘that Charles could have envisaged deploying Catholic troops on the mainland of Protestant Britain, after decades of intense sectarian warfare across Continental Europe, confirmed a capacity to devise strategies that were deeply provocative and practically ineffectual in equal measure.’

There was no Continental invasion during the decade of fighting, not even after the public execution of the defeated king outside his own palace, ‘like a common criminal’, as the Venetian envoy put it. ‘You cut off heads as only popes have done,’ a Dutch poem ‘Op de koning-dooders’ (‘On the King-Killers’) began: ‘You’ve crossed a Rubicon uncrossed by anyone.’ Agents of the new republic were assassinated abroad – Isaac Dorislaus at The Hague in 1649, Anthony Ascham in Madrid in 1650 – and the ‘all devouring English devils’ were denounced as ‘rat-catchers, dog-butchers, manure-sweepers, cutpurses, privy-cleaners [and] animal-castraters’. But there was a grudging respect for that ‘Hell-cat’ Cromwell, as Cardinal Mazarin called him, and for England’s new militarism. Between 1651 and 1654 as many new warships were built, in tonnage, as in the half-century before the civil war. By 1655, the Protectorate was hosting permanent embassies from six Continental monarchies and several smaller delegations. ‘Never was there a usurper so solemnly acknowledged,’ the Dutch-born diplomat Abraham de Wicquefort wrote. A Parisian cartoon in 1655 showed Cromwell seated ‘at his business’ with the kings of Spain and France on either side ‘offering him paper to wipe his breech’.

Ironically, Cromwell was one of the few people who did believe that England was infested with devils. Following his first military defeat – a disastrous assault on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola in 1655 – he deduced that God was punishing the English for their sins. His unpopular, short-lived solution was the rule of the major-generals – the division of the country into military districts and a clampdown on gambling, drunkenness and fornication. Paradise was lost when the monarchy was restored in 1660, but plenty of fallen angels remained to conspire against Charles I’s sons, the heirless king, and James, who succeeded in 1685. Jackson stresses the precarity of the dynasty in these decades and the complexity of a foreign policy which at one point saw Charles II taking secret subsidies from Louis XIV while at the same time Parliament approved funds to fight a war against France. England’s mercurial character remained a source of bafflement to her Continental cousins. In 1678 the anonymous author of A Letter from Amsterdam to a Friend in England described it as ‘either the floating island, or founded upon quicksilver’.

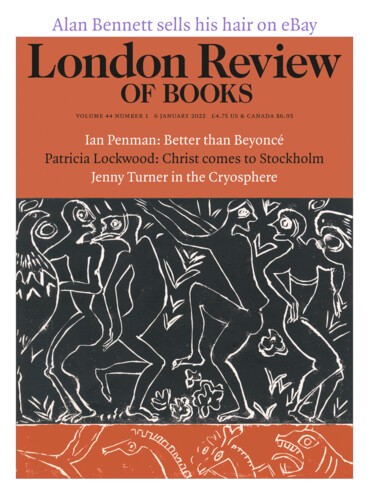

England’s unease is also conveyed by Devil-Land’s front cover, a detail from a Jacobean charter, which shows a robin redbreast – that most territorial of birds – perched on a branch ripe with berries. It’s impossible to tell if it is poised for fight, flight or song. The English tried all three in this century and I’d have loved to have heard more song: Milton’s epic poetry, for example, or a few more lines from Andrew Marvell who, like Milton, had a diplomatic role in this period. Jackson briefly but brilliantly discusses Marvell’s ‘Last Instructions to a Painter’, a satire of 1667 which portrays a dissolute Charles II with his mind on his codpiece rather than the national interest. She also provides tantalising glimpses of England’s soft power, including the role of Charles I’s art collection in facilitating Spain’s accreditation of the republic, but mostly she keeps course with the geopolitical rapids that threw England, latterly, into the expansionist arms of France.

The fear of popish invasion which dominated English politics for much of the century finally clarified as a choice between popery or invasion. James II claimed to want religious toleration – ‘a Magna Carta for conscience’ – but he became king in the same year his cousin Louis XIV outlawed Protestantism in France. When James’s queen, Mary of Modena, unexpectedly had a son three years later, the intolerable prospect of an unending succession of Catholic Stuarts prompted seven English nobles to invite the Protestant William, the Dutch Stadtholder, to take the throne with his wife, James’s daughter Mary. On 5 November 1688, the English celebrated their deliverance from popery by welcoming a foreign flotilla the size of the Armada into the English Channel.

Hobbes had died nine years earlier, nearly lasting the course of Devil-Land’s century. His solution to dealing with the ‘unstable fissures and vulnerable fragilities’ so expertly exposed in this history was an absolute sovereign, installed by the covenant of the people to protect them from their basest instincts. William III, in need of money to fight the French, put his trust in Parliament instead. He was the first monarch in English history to summon parliamentary sessions in every year of his reign. In 1694 the Bank of England was created to finance the war effort. England’s institutions and borders were more secure at the end of the 17th century than at the beginning, but at the cost of a new commitment to Europe.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.