On a hot day in August 1806, Jean-Honoré Fragonard stepped into a café near the Champs de Mars to eat an ice cream, collapsed, and died later that day of ‘cerebral congestion’. He was 74 and by this time virtually unknown – a few lines in the daily papers were the only acknowledgment of his death. As an artist, Fragonard had often been at odds with the culture of his day. He took up the Rococo idiom decades after it had gone out of fashion, appearing to his contemporaries as aesthetically belated. His ebullient scenes of play and pleasure were seen as frivolities in a climate of moral seriousness. His career choices, too, went against the grain.

Things started well. Born to a glove-making family in Grasse, Fragonard was articled to a Paris notary as a teenager but his artistic talent was spotted and it was suggested that he study under François Boucher. Boucher sent him for preliminary training with Chardin: six months later Fragonard returned, painting so well that Boucher entrusted him to make reproductions of his own work. He won the Prix de Rome in 1752 and had his debut at the Paris Salon of 1765 with Coresus Sacrificing Himself to Save Callirhoe, a neo-Baroque spectacle that caused a sensation. Diderot wrote an enthusiastic review in the form of a philosophical dream. But his submissions two years later – much less ambitious in style and format – were considered disappointing, and Diderot dismissed a painting of plump putti frolicking in the sky as a ‘beautifully prepared omelette, moist, yellow and slightly burned’. Soon afterwards, Fragonard decided to abandon the academic career – and with it, access to the Salon exhibitions and royal patronage – turning to commissions from private patrons, often on erotic subjects. Observers complained that he was squandering his talent. Commenting on Fragonard’s absence from the Salon of 1769, Louis Petit de Bachaumont (writing anonymously in the Mémoires secrets) noted that ‘instead of working for glory, and for posterity, he contents himself to shine in boudoirs and in dressing rooms.’

Fragonard departed from his predecessors, in particular Boucher, in choosing contemporary subjects for his erotic scenes, rather than painting the exploits of nymphs and goddesses. In works such as The Happy Lovers (1770), the amorous pair have lost all marks of social status; there are no mythological attributes, heavenly adornments or distinguishing items to tell us who we are looking at. They are defined by their act, by the pursuit of desire. For Watteau or Jean-François de Troy, the sexual encounter was an elaborate social ritual. Fragonard represents it as a physical act that absorbs the couple entirely, taking them beyond society: their arms enlaced and their faces, joined by a kiss, obscured from the viewer. In characteristic lively brushstrokes, he emphasises the rush of blood to their cheeks, the weight and inclination of bodies suspended in swooning instability.

Such paintings might not have earned Fragonard critical approval at the time, but they appear with hindsight exemplars of the new epistemology of sex that was emerging in France. After the Counter-Reformation, sex was seen as an activity apart – one that required privacy, concealment – but Fragonard insisted that it could also be depicted, and therefore discussed. The anonymous bodies of the Happy Lovers are, like the machines à jouir of the materialist philosopher Julien Offray de la Mettrie, natural and impulsive in their sexuality. Fragonard’s erotic art has much in common with pornographic literature of the time – an important tool for disseminating materialist views in the second half of the 18th century – and it’s not difficult to argue against accusations that he was simply retardataire. But he was no provocateur either (apart from anything else, he avoids genital explicitness).

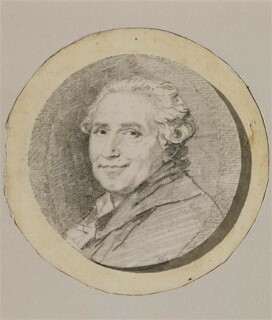

Interpretation of Fragonard’s work has been hampered by a paucity of sources. While his paintings and drawings were sought after by collectors and amateurs, and fetched notoriously high prices, his withdrawal from the Salon exhibitions meant they were little discussed. Nothing written by Fragonard himself has survived (it has been argued that he was illiterate, though this is unlikely) and biographical information is scarce. Anecdotal evidence attests to his widely publicised mishaps and to his conflicts with some of his most significant patrons, including the famous dancer Mademoiselle Guimard as well as Madame du Barry and the rich fermier général Bergeret de Grancourt. Fragonard seems to have been unable or unwilling to play the social game at which his friend and colleague Hubert Robert excelled. In his infrequent self-portraits, Fragonard preferred to depict himself in the same tondo format that he used to paint his wife, Marie-Anne Gérard; his sister-in-law, Marguerite (who moved in with the couple in 1775); his daughter, Rosalie; and his son, Alexandre-Évariste. These tell us something about the real locus of privacy for Fragonard – not sex and sexuality but the family.

If biography has proved elusive, so too has a reliable chronology of the works. Many of Fragonard’s commissions weren’t recorded and he often painted on spec. The occasion for some of his projects, notably the late series of drawings illustrating Orlando Furioso, remains mysterious. We don’t know if these were commissioned or done for personal pleasure. Nor do we have any idea why Fragonard more or less gave up painting in his fifties, though the Revolution probably had something to do with it. Much of what we do know about him has been shaped by his reception in the 19th century. Having been utterly forgotten, he was rediscovered more than fifty years after his death as part of the broader Rococo revival. Many long-unseen works were included in a large exhibition of French art at the Galerie Martinet in 1860, and Louis La Caze’s donation of his private collection to the Louvre in 1869 made it possible to see a number of Fragonard paintings in public for the first time. In 1865, the Goncourt brothers published an appreciation, incorporating biographical information obtained from Fragonard’s grandson, Théophile.

Central to the reassessment of Fragonard was his rediscovery by Manet and the Impressionists. Fragonard’s open manner, his bold use of colour and rapidity of execution suggested an alternative model to the studious painting of the academy. His Fantasy Figures, first seen at the Martinet gallery and then at the Louvre, were especially influential. These extraordinary paintings show his friends and patrons – including the Abbé de Saint-Non – as imaginary characters. Fragonard dressed them in theatrical costumes à l’espagnole and painted them with exceptional brio and chromatic brilliance. The paintings appear more his own inventions than portraits of real people. On a label attached to the reverse of Saint-Non, Fragonard boasted that it took him just ‘an hour’s time’. The bravado isn’t only in the execution: Fragonard was openly declaring his right to do what he liked with his sitters, to turn a portrait into a fantasy of his own making. Manet’s self-referential depictions of models in Spanish costume are indebted to the Fantasy Figures, and there is a more distant echo in Matisse’s Woman in a Hat from 1905. Berthe Morisot developed her slashing-strokes style of painting by emulating what critics referred to as Fragonard’s vives pochades (‘lively sketches’).

Serious analysis of Fragonard’s output began with Roger Portalis’s two-volume monograph of 1889. Since then, the dominant view of him has been as the quintessential painter of eros – the Goncourts called him ‘a Cherubino of erotic painting’ after the Marriage of Figaro character who falls in love with everyone he meets. In Fragonard: Art and Eroticism (1990), Mary Sheriff argued that his thematic commitment to eros was expressed stylistically, in the impetuousness of his brushwork. More recent writing on Fragonard has focused on establishing a nuanced historical understanding of sex and romance in the period. Exhibitions such as Fragonard amoureux at the Musée du Luxembourg in 2015 have drawn helpful links with different aspects of 18th-century erotic culture, including the codes of galanterie and libertinage. All this has enriched the discourse, but it hasn’t changed the critical framework.

Satish Padiyar’s book strikes a different note. Although he doesn’t ignore erotic iconography, he considers Fragonard above all as a painter of time. The temporality that interests him resides not in a work’s relation to the past, or in its materials, but in its subject and visual structure. This can be seen in paintings such as The Small Park or The Island of Love, where elisions in the pictorial narrative make the stories they tell mysterious or illegible. Padiyar also points to Fragonard’s deliberately unco-ordinated, disjunctive use of different media, as in View of a Park, where the aqueous areas of ink wash and watercolour spill beyond the contours defined by the graphite drawing. Unity of time and space comes apart in the Progress of Love cycle, where the ‘tempo of life’ is subjected to ‘strange contortions and disruptions’. Padiyar extends the idea to encompass Fragonard’s personal and professional behaviour: his abandonment of the state commission to paint the ceiling of the Galerie d’Apollon at the Louvre and his quitting Mlle Guimard’s house before completing its decor are taken as symptoms of a systematically achronic attitude.

Padiyar organises his discussion around three categories: ‘Secrets’, ‘Surprise’ and ‘Dreams’. Secrecy is both the subject of some paintings – The Love Letter, for instance, where a woman holding a bouquet of flowers and (we presume) a lover’s note casts a furtive look at the viewer – and also a structural device: in The Stolen Shift we gaze as if through a peephole at a young woman being undressed. But Padiyar also considers ‘secrecy’ more broadly, such as the private pleasures of motherhood depicted in The First Step and The Beloved Child, late paintings that Fragonard produced in collaboration with his sister-in-law, Marguerite Gérard. Bearing stylistic traces of both painters, these works carry their own secret: who was their author? Can one ascribe them to Fragonard, to Fragonard assisted by Gérard, or to Gérard alone? While supporting the notion of joint authorship, Padiyar makes an intriguing suggestion: rather than assuming that it was Gérard who benefited from the association, as most art historians have, he asks if the collaboration might have allowed Fragonard – ageing and increasingly insecure – to take advantage of a younger artist’s name and talent. The paintings were made in the 1780s, as Fragonard was abandoning his practice. A recently rediscovered series of drawings from the same time, in which Fragonard satirises his own ankle injury and recovery (he had tripped on a high doorstep), is self-deprecating but also supports the notion that he felt less sure of himself than before. The final image shows Fragonard crouched low, hobbling behind a young woman believed to represent Gérard and holding onto her skirts.

Padiyar argues that it was Fragonard’s liking for privacy and opacity, rather than financial considerations or accidents of patronage, that determined his artistic choices: a form of self-conscious resistance to the Enlightenment’s promotion of publicness and transparency. Padiyar sees Fragonard’s images of stolen shifts and furtive kisses as evidence of cultural non-conformity and, as such, a means of asserting his artistic and personal freedom. Non-conformity is manifest in paintings such as The Swing, The Bolt and the Progress of Love series, which exemplify what Thomas Kavanagh has called Fragonard’s ‘aesthetics of the moment’. Padiyar recasts the notion of the moment in more dynamic terms, however, as a pictorial act that interrupts the flow of events, creating a gap in time that pulls the viewer in. The 17th-century painter and theorist Roger de Piles, who argued for the direct, sensory appeal of painting over its intellectual merits, wrote that the best artworks could be grasped in a single glance, a coup d’oeil. The achievement of a painting lay in its ability to produce a direct bodily response, rather than its demand for sustained mental consideration. For de Piles the effect was similar to erotic seduction; Padiyar conceives of it as something more disruptive, which jolts us out of our surroundings. Like Fragonard’s protagonists, the viewer is vulnerable to ‘the irruptions of chance happenings’.

This allows Padiyar to see a painting like The Swing as an event – erupting femininity that disrupts the voyeuristic structure of the image – rather than a narrative. Propelled into space by the movement of the swing, the woman, wrapped in billowing pink and white, is a burst of colour, set apart from the rest of the scene. She is the surprise, in Padiyar’s terminology, while her male companions remain half camouflaged in the dappled shade of the trees.

The Progress of Love series was painted for Madame du Barry’s pleasure pavilion in Louveciennes, but the panels were removed shortly after their installation and replaced by the work of another artist, humiliating Fragonard. They are now at the Frick in New York and generally considered his highest achievement. Padiyar’s interpretation, which adds to an already substantial discourse, is concerned with immediacy as both the overt subject of two panels – The Meeting (sometimes called The Surprise) and The Pursuit – and as the formal logic of the entire cycle. The co-existence of diverse, often clashing tempos within the panels (for example, the stasis of the couple in The Lover Crowned compared with the tumult of vegetation around them) produces a destabilising effect that Padiyar suggests may have been the cause for du Barry’s rejection of them.

His theory meets its limit in the section on the 18th-century subject par excellence, the kiss, which ends in an analysis of The Bolt. Painted in the late 1770s for the Marquis de Véri, The Bolt was unusual in being famous in Fragonard’s lifetime (it fetched nearly four thousand livres after de Véri’s death in 1785). It shows a couple entangled: the man, having seized his consort with one arm, shuts the bolt on the bedroom door with the other. It isn’t clear whether we are looking at a moment of intense sexual arousal (judging from the disorder of the bed, they may have already engaged in some sexual act) or something more pernicious. Is the woman’s resistance feigned, part of the game of seduction according to the protocols of libertinage, or is her ravishment tantamount to rape?

The temporal dimension that interests Padiyar has little bearing on the matter of what is being represented here. As an event, rape seems to me to go far beyond the idea of surprise – that’s the least of it. Even in the subversive sense proposed by the book, ‘surprise’ is an insufficient critical framework for making sense of sexual violence. Nor is it helpful in thinking about the questions of consent and agency that other scholars have raised. Padiyar eventually resorts to a contextual reading, unrelated to temporality, in order to explain what he takes to be Fragonard’s latently critical vision of rape. But why then include this painting at all? As for his interpretation, I remain unconvinced. Fragonard’s aesthetic privileging of the male figure – the man’s powerful body suggests both physical beauty and sexual freedom – over the female (a listless doll in satin) does not exactly connote moral anxiety.

In his third chapter, Padiyar uses the idea of the dream to discuss Fragonard’s innovative drawing practice. Fragonard was an extraordinary and prolific draughtsman (he was said to shed sketches like leaves) and his drawings were highly appreciated – and highly remunerated – by his contemporaries. This coincided with the rising status of drawings in the second half of the 18th century, when for the first time they were collected, exhibited and discussed in their own right. The focus here is on the body of work Fragonard produced during his second visit to Italy, in 1773-74, with his patron Bergeret de Grancourt, Saint-Non’s brother-in-law. The drawings are unusual in their asynchronic use of graphite, chalk and ink wash, as well as in their execution: fluid landscapes populated by lightly sketched figures, whose actions and attributes are difficult to discern. Padiyar likens them to daydreams and suggests that Fragonard’s vision of Italy as a personal reverie contributed to his conflict with Bergeret, recorded in the latter’s travel journal. He was an evasive travel companion – Bergeret complained that he didn’t fulfil his function as a Grand Tour guide – and his oneiric drawings could be interpreted as uncommunicative, even anti-social.

Yet if this dreamy style was a rejection of his patron, as Padiyar suggests, it seems to have been lost on Bergeret, who was so covetous of the Italian drawings that he tried to appropriate them all, with the result that Fragonard took him to court. Another explanation for the dreaminess of the drawings would be that they were influenced by the new technique of aquatint, practised in Fragonard’s immediate circle by Saint-Non and others. Saint-Non had used it in combination with etching to reproduce the drawings from Fragonard’s first Italian trip, publishing them in two volumes in 1770. Such translation from one medium to another was typical of the thriving intermedial culture of late 18th-century France in which, as Perrin Stein and others have shown, Fragonard was deeply engaged.

Padiyar gives little sense of the historical conditions that may have influenced Fragonard’s idiosyncratic approach to time. It would have been helpful to hear more about contemporary arguments for time as a subjective process, about the growing use of portable timekeeping devices and the novel idea of time as a personal possession. It is certainly worthwhile to consider the ways in which Fragonard’s delays and abdications made his art possible, rather than seeing them as self-imposed blows to his career, and Padiyar is convincing when he argues that in rejecting certain artistic norms Fragonard was adopting a politics – one that pursued not only sexual but also religious and political freedoms. It restores seriousness to a body of work often characterised by a certain légèreté, and to an artist who can seem light-hearted even in the manner of his death.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.